Essentials of Research

Key terms

10 essentials

Design

Ethics

Philosophical foundation

Query

Question

Theory

Researchers who pursue either naturalistic or experimental-type inquiry confront similar challenges and requirements when conducting research. However, these are interpreted and acted on differently, depending on the type of inquiry pursued. We categorize the challenges and requirements of any type of research endeavor into what we call the 10 essentials of the research process (Box 2-1).

Each subsequent chapter in this book focuses on one particular research essential and examines its components from the perspectives of both naturalistic inquiry and experimental-type research. Consider this chapter as a brief summary of the entire text. You may want to read this chapter quickly and then refer to it as you make your way through the text as a way to summarize the meaning of each essential. You can refer to Table 2-1 as a quick guide as well.

TABLE 2-1

| Essential | Explanation | Process |

| Identify a philosophical foundation | Reveal underlying assumptions of ontology and epistemology | Thinking |

| Frame a research problem | Identify broad topic or problem area | Thinking |

| Determine supporting knowledge | Review and synthesize existing literature to examine knowledge development in identified problem area | Thinking/Action |

| Identify a theory base | Use existing theory to frame research problem and interpret result, or construct theory as part of research process | Thinking |

| Develop a specific question or query | Identify specific focus for research, based on knowledge development, theoretical perspective, and research purpose | Thinking |

| Select a design strategy | Develop standard procedures or broad strategic approach to answer research question or query | Thinking |

| Set study boundaries | Establish scope of study and methods for accessing research participants | Action |

| Obtain information | Determine strategies for collecting information that is numerical, visual, auditory, or narrative | Action |

| Analyze information and draw conclusions | Employ systematic processes to examine different types of data and derive interpretative scheme | Action |

| Share and use research knowledge | Write and disseminate research conclusions | Action |

Ten essentials of research

The 10 research essentials and their order of presentation in this book should not be construed as representing a step-by-step, procedural, or “recipe”-type approach to the research process. Each essential is highly interrelated and may not necessarily occur in the order in which it is presented in Box 2-1 and in this text. The order depends on the research tradition and design that you select.

Experimental-type research is hierarchical in its sequence and approach. It tends to follow the 10 essentials in a precise, ordered, and highly structured manner such that each essential purposely builds on the other in a linear, systematic, and stepwise manner. Figure 2-1 depicts this linear approach, and the graphic is used throughout this book to describe the enactment of the 10 essentials. However, it is important to note that even within experimental-type research, the 10 essentials are not mutually exclusive. As one moves along stepwise, previous steps may be revised as a consequence of new methodological decisions.

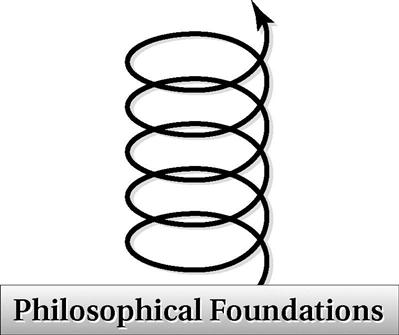

Naturalistic inquiry, in contrast, embodies the 10 essentials using more diverse and complex processes, in which each essential is related to the other and revisited at different points throughout the research process. This spiral image, used throughout this book to depict this type of inquiry (Figure 2-2), links the 10 essentials in different orders, depending on the specific philosophical foundation in which the research is based. The sequences of the 10 essentials within each research tradition in naturalistic inquiry will become clear as you make your way through this book. Let us briefly examine the meaning of each essential.

Identify a Philosophical Foundation

Identifying a philosophical foundation is an important essential that occurs first or in the early stages of the research process. By philosophical foundation, we mean an individual’s particular orientation to how a person learns about human behavior, health, and personal abilities and experiences or other phenomena of importance in health and human services. In Chapter 3, we classify these orientations into two overarching philosophical categories through which knowledge is viewed and built, each of which gives rise to one of the primary research traditions. Thus, the researcher’s particular philosophical orientation toward learning about phenomena determines the specific research tradition that is selected: experimental-type, naturalistic inquiry, or an integration of the two.

In naturalistic inquiry, articulating a philosophical tradition is especially important because of the many distinct philosophical schools of thought that inform this research approach (see Chapter 3). In preparing a proposal to conduct a research study or in writing a report of the completed study, the researcher using naturalistic inquiry usually discusses his or her philosophical perspective to provide an understanding of the thinking context in which the research is conducted.

In contrast, experimental-type research is based on one unifying philosophical foundation—logical positivism. Positivism is a broad term that refers to the belief that there is one truth independent of the investigator and that this truth can be discovered by following strict procedures (see Chapter 3). It is not necessary for an experimental-type researcher to identify the philosophical root of his or her research when submitting a research proposal or a published report, because all experimental-type inquiry is based on a single philosophical base. For example, a researcher trained in survey techniques will naturally assume a positivist or empiricist approach to describe a particular phenomenon. Therefore, it is not necessary for this researcher to state formally the epistemological assumption embedded in the study.

A philosophical foundation provides the backdrop from which specific methodological decisions in research are made. This does not mean that you must first become a philosopher to participate in research. However, you do need to know that research methodologies reflect different assumptions about human behavior, experience, meaning, and knowledge and about how we learn about these phenomena. By selecting a particular research strategy, you will automatically adopt a particular worldview and philosophical foundation. We believe that, at the very least, you should be aware that you are adopting a specific set of assumptions about human behavior and how people come to understand it. Understanding this philosophical foundation is particularly critical because assumptions about knowledge and their use have major implications for how health and human service professionals understand and respond to the diversity of human characteristics.

How does one’s philosophical foundation shape research decisions? Consider the example of a provider who is hired to design and examine a pregnancy prevention program for Asian-American teenagers. From a logical positive tradition, one approach would be to select an existing and previously validated program, or what is referred to as an evidence-based program, and then implement and test it to ascertain its effectiveness in achieving pregnancy prevention for this particular group. In contrast, a naturalistic researcher would begin by discovering the cultural norms and values of Asian-American teenagers that might be important to informing a prevention program and then, based on this knowledge, construct an intervention tailored to that group. Each research approach has its advantages and limitations that you will learn about in this book.

You probably already have a particular philosophical foundation or preferred way of knowing without fully labeling or recognizing it as such. Sometimes personality, or how one naturally views the world, influences the particular research direction that is adopted. If you prefer to make and follow detailed plans, if you feel uncomfortable with the view that values and biases shape one’s worldview, or if you do not like “hanging out” in someone else’s world and trying to uncover his or her perspectives or experiences, you may have difficulty with naturalistic inquiry. In contrast, if you are uncomfortable working with and understanding numerical values or feel that numbers do not capture the complexity of the human experience, you may have difficulty with experimental-type inquiries. Many articles have been written about the personality types of individuals who pursue naturalistic inquiry versus those who pursue experimental-type research. However, there is nothing definitive about this literature. Certainly, all types of personalities are capable of learning the practices of multiple research paradigms. Also, as you will learn, it is possible for one researcher to work out of both research paradigms or to use an approach that integrates the two.

Frame a Research Problem

To engage in the research process, the investigator must identify in advance a particular problem area or broad issue that necessitates systematic investigation. Research, regardless of the form of inquiry used, is a focused, systematic endeavor that addresses a social issue, theoretically derived prediction, practice question, or personal concern. One of the first thinking processes in which you must engage is the identification of the problem area and the specific purpose for your research. Research topics should come from personal, professional, theoretical, scholarly, political, or societal concerns. To engage in research, it is important that you identify an area that holds personal interest and meaning to you. The research process is challenging and requires time and commitment. You will quickly lose momentum if you do not pursue a topic of personal intrigue. Some researchers study areas that have been problematic in their own lives. For example, some investigators who pursue studies on chronic illness have had a personal encounter with chronicity, such as growing up with a sibling or parent with chronic illness. Research in an area that has personal significance provides a scholarly forum from which to examine and then personally understand the issues. This is not to say that you have to be an individual with chronic illness to want to study this area or that you need to have experienced chronic illness or child abuse to study the phenomenon. However, something about a topic should “grab” you. It has to have personal meaning or some level of importance to your life—intellectually, emotionally, or professionally—for the research endeavor to be personally worthwhile. Because research is a long and engaging process, being passionate about a particular topic area or problem is important.

Once you have identified a topic (e.g., coping strategies of culturally diverse caregivers of individuals with dementia; impact of maternal alcohol abuse on early childhood development; quality of life and individuals with multiple sclerosis), you can begin to think about your particular purpose in exploring the topic. What do you want to know about the topic? What will be the purpose of your particular research, and how will the knowledge gained be used? To determine the direction, purpose, and uses of a study, the researcher must read what is already known about the topic.

Determine and Evaluate Supporting Knowledge

Another research essential involves conducting a critical review of existing theory and research that concerns your topic or area of inquiry.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Researchers who identify their philosophical perspective as symbolic interaction tend to use highly interpretative forms of naturalistic inquiry that focus on the meanings and behaviors of individuals in social interaction. These researchers tend to pursue ethnographic research methodology. In contrast, researchers who identify with the philosophical foundation of phenomenology will focus on particular personal experiences of individuals, such as patients living with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), ethnic minorities interacting with health care providers, or how each gender perceives a sense of self. Researchers working in a phenomenological tradition tend to pursue methodologies that elicit the telling of a person’s personal story or narrative using a variety of sources, including personal interactions, interviews, and diary reviews.

Researchers who identify their philosophical perspective as symbolic interaction tend to use highly interpretative forms of naturalistic inquiry that focus on the meanings and behaviors of individuals in social interaction. These researchers tend to pursue ethnographic research methodology. In contrast, researchers who identify with the philosophical foundation of phenomenology will focus on particular personal experiences of individuals, such as patients living with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), ethnic minorities interacting with health care providers, or how each gender perceives a sense of self. Researchers working in a phenomenological tradition tend to pursue methodologies that elicit the telling of a person’s personal story or narrative using a variety of sources, including personal interactions, interviews, and diary reviews. Let us assume, on the basis of your practice with individuals hospitalized with spinal cord injury, that to improve their care you need to know more about their self-care practices and social supports after they return home. This information would help determine the types of skills training that would be important to introduce in the hospital and how best to prepare your patients for the challenges they will confront at home. You believe this area of concern is important to investigate. What do you think your first task will be? It will be to determine what is already known in the published literature. If there is little or no knowledge about the topic, then you will need to design a study that obtains foundational knowledge and that initially describes self-care practices and the role of social networks. If there is some descriptive knowledge of daily practices but little information about whether these practices differ across diverse populations and are associated with having social supports, you may want to conduct a study that investigates these aspects of the topic. Alternatively, suppose there is a body of well-constructed knowledge about gender and ethnic differences in practices of caregivers. This information may lead you to examine the impact of these practices on the general well-being and self-care of individuals who will be discharged to their homes after spinal cord injury. Existing literature should be used to help identify and guide the direction of the research you plan to pursue to build knowledge in your area of interest.

Let us assume, on the basis of your practice with individuals hospitalized with spinal cord injury, that to improve their care you need to know more about their self-care practices and social supports after they return home. This information would help determine the types of skills training that would be important to introduce in the hospital and how best to prepare your patients for the challenges they will confront at home. You believe this area of concern is important to investigate. What do you think your first task will be? It will be to determine what is already known in the published literature. If there is little or no knowledge about the topic, then you will need to design a study that obtains foundational knowledge and that initially describes self-care practices and the role of social networks. If there is some descriptive knowledge of daily practices but little information about whether these practices differ across diverse populations and are associated with having social supports, you may want to conduct a study that investigates these aspects of the topic. Alternatively, suppose there is a body of well-constructed knowledge about gender and ethnic differences in practices of caregivers. This information may lead you to examine the impact of these practices on the general well-being and self-care of individuals who will be discharged to their homes after spinal cord injury. Existing literature should be used to help identify and guide the direction of the research you plan to pursue to build knowledge in your area of interest.