Senior Health

Mary Ellen Trail Ross and Edith B. Summerlin

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

2. Discuss the demographic characteristics of the elderly population.

3. Describe psychosocial issues related to aging.

4. Describe physiological changes due to aging.

5. Recognize Healthy People 2020 wellness goals and objectives for older adults.

6. Describe health/illness concerns common to the elderly population.

7. Identify nursing actions that address the needs of older adults.

Key terms

advance directives

aging

alternative housing options

Alzheimer’s disease

anxiety disorder

crime

depression

elder abuse

falls

glaucoma

guardianship

macular degeneration

Medicaid

Medicare

Social Security

suicide

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

In America, individuals aged 65 years or older are an important and growing segment of the population. Life expectancy is increasing; thus, larger numbers of people are reaching 65 years of age and older. In view of the increasing number of seniors who potentially will remain living in the community, the role of the community health nurse becomes very important in helping these seniors to continue to live independently and to increase their years of healthy life. For community health nurses to assist older adults, they must be familiar with the characteristics of seniors, their socioeconomic situations, their health behaviors, health status, health risks, and available community resources. This chapter discusses these issues and gives suggestions as to how community health nurses might address them.

Concept of aging

Aging is a natural process that affects all living organisms. The concept of aging is most often defined chronologically. Chronological age refers to the number of years a person has lived. In the United States, an older adult is generally defined as one who is 65 years of age or older. However, it is important to remember that older adults cannot be grouped collectively as just one segment of the population. The older adult population is a heterogeneous group. The young-old (aged 65 to 74 years), the middle-old (aged 75 to 84 years), the old-old (aged 85 to 99 years), and the elite-old (more than 100 years old) are four distinct cohort groups (Ebersole et al., 2008).

Functional age, on the other hand, refers to functioning and the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing and grooming, and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as cooking and shopping. This definition of aging is a better measure of age than chronological age. After all, most older adults are more concerned with their functional ability than their chronological age. Assisting older adults to remain independent and functional is a major focus of nursing care.

Theories of aging

Since early times, scientists have attempted to explain why humans age. There are many biological and psychosocial theories of aging. Biological theories of aging answer questions such as “How do cells age?” and “What triggers the actual aging process?” (Miller, 2009). The biological theories can be subdivided into two main divisions: stochastic and nonstochastic. Stochastic theories explain aging as events that occur randomly and accumulate over time, whereas nonstochastic theories view aging as predetermined. Some of the popular biological theories are included in Box 19-1.

The three classic psychosocial theories of aging are behavioristic and examine how humans experience late life. The disengagement theory, proposed by Cumming and Henry (1961), states that aging is inevitable, with mutual withdrawal or disengagement common; this results in decreased interaction between the aging person and others. The activity theory posits that activity is necessary to maintain life satisfaction and a positive self-concept (Lemon, Bengston, and Peterson, 1972; Maddox, 1963). The continuity theory suggests that a person continues through life in a similar fashion as in previous years (Havighurst, Neugarten, and Tobin, 1968).

Concepts gleaned from the various theories are useful to nurses as they care for older adults. For example, knowledge that the immune system is affected by aging implies the need for nurses to be vigilant about preventing infections (Miller, 2009). Psychosocial theories of aging point out the uniqueness of older individuals as they age and make life adjustments. Knowledge of these theories may help nurses to dispel common myths of aging.

Demographic characteristics

Population

Americans are living longer than ever before, and it is expected that the older population will continue to grow. Presently, people who survive to age 65 years can expect to live an average of nearly 18 more years. The life expectancy of people who survive to age 85 years today is about 7 more years for women and 6 more years for men. Life expectancy varies by race, but the difference decreases with age. In 1900, people aged 65 years and older made up 4% of the population. In 2006, nearly 37 million people aged 65 years and over lived in the United States, accounting for just over 12% of the total population. The oldest-old population (those 85 years and older) grew from just over 100,000 in 1900 to 5.3 million in 2006 (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008). There are about 40,000 centenarians in the United States (Ebersole et al., 2008).

The baby boomers (individuals born between 1946 and 1964) will start turning 65 years old in 2011, and the number of older adults will increase dramatically. By 2030, the number of Americans aged 65 years and older is expected to be twice as large as their counterparts in 2000, growing from 35 million to 71.5 million, and will represent nearly 20% of the total U.S. population. The greatest growth will occur in the population aged 85 years and older, whose numbers are projected to grow from 5.3 million in 2006 to nearly 21 million by 2050 (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008).

Racial and Ethnic Composition

In addition to growing larger, the older population is becoming more diverse, as is the rest of the population. In 2006, non-Hispanic whites accounted for nearly 81% of the U.S. older population. Blacks made up 9%, Asians made up 3%, and Hispanics (of any race) accounted for 6% of the older population. The older population will grow among all racial and ethnic groups; however, the older Hispanic population is projected to grow the fastest (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008).

Geographic Location

The proportion of the population aged 65 years and over varies by state. In 2006, Florida had the highest proportion of people aged 65 years and over (17%). Pennsylvania and West Virginia also had high proportions, each slightly over 15% (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008). The nine states with the largest number of elderly individuals (1 million or more) are California, Florida, New York, Texas, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey (Administration on Aging, 2001).

Gender

Older women outnumber older men in the United States. In 2006, women accounted for 58% of the population aged 65 years and over and 68% of the population aged 85 years and over (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008).

Marital Status

Older men are more likely than older women to be married. In 2007, more than three quarters (78%) of men aged 65 to 74 years were married, compared with more than half (57%) of women in the same age-group. The proportion married is lower at older ages: 38% of women aged 75 to 84 and 15% of women aged 85 years and over were married. Widowhood is more common among older women than older men. Women aged 65 years and over were three times as likely as men of the same age to be widowed: 42% compared with 13%. In 2007, 76% of women aged 85 years and over were widowed, compared with 34% of men. Relatively small proportions of older men (8%) and women (10%) were divorced in 2007, and a small proportion of the older population has never married (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008).

Education

Educational attainment has increased among older adults. In 2007, 76% of older adults were high school graduates (compared with 24% in 1965). Older blacks and Hispanics aged 65 years and older completed high school at lower rates than their white and Asian counterparts (58% and 42%, compared with 81% and 72%). In 2007, 19% of older adults had a bachelor’s degree or higher (compared with 5% in 1965). Older Asians had the highest proportion with a bachelor’s degree or higher (32%), compared with 21% for non-Hispanic whites, 10% for blacks, and 9% for Hispanics. Older men attained a bachelor’s degree more often than older women (25% compared with 15%); however, the gender gap in completion of a college education is narrowing (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008).

Living Arrangements

As age increases and widowhood rates rise, the percentage of the population living alone increases accordingly. In 2007, 73% of older men lived with their spouse, whereas fewer than one half (42%) of older women did. In contrast, older women were more than twice as likely as older men to live alone (39% and 19%, respectively). Older Hispanic (33%), black (32%), and Asian (30%) women were more likely than white women (14%) to live with relatives other than a spouse. Older white and black women were more likely than women of other races to live alone (approximately 40% each, compared with about 20% for Asian and 26% for Hispanic women). Older black men (29%) lived alone more than three times as often as older Asian men (8%). Older Hispanic men were more likely (17%) than men of other races and ethnicities to live with relatives other than a spouse (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008).

Housing and Residential Services

Older adults typically prefer to “age in place” or live in their own home for as long as possible. In 2005, 93% of Medicare enrollees aged 65 years and over resided in traditional community settings. Two percent of the Medicare population aged 65 years and over resided in community housing with at least one service available, such as meal preparation, housekeeping, laundry, and assistance with medication. Approximately 5% resided in long-term-care facilities. The percentage of people residing in community housing with services and in long-term-care facilities was higher for the older age-groups. For example, among older adults aged 85 years and older, 76% resided in traditional housing, whereas 7% resided in community housing with services and 17% resided in long-term-care facilities (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008).

Alternative Housing Options for Older Adults

The significant majority (93%) of older adults aged 65 years and older reside in the traditional, single-family home; however, some choose to downsize to smaller housing, such as townhouses or condominiums, where maintenance needs are eliminated or minimized. As mentioned, in 2005, only about 2% of elders aged 65 years and over resided in community housing with at least one service available. The types of alternative housing options included retirement communities or apartments, continuing-care retirement facilities, assisted-living facilities, and board and care facilities/homes. Services at these facilities include meal preparation, housekeeping, laundry, and medication administration. Approximately 5% of older adults reside in long-term-care facilities that provide 24-hour personal and/or skilled care, 7 days a week. The percentage of people residing in community housing with services and in long-term-care facilities is higher for individuals aged 85 years and older. These older adults generally have more functional limitations (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008). It is important to note that many older adults who would like to change current living arrangements find that organized senior housing is too expensive for middle-class and lower-middle-class citizens. On the other hand, these individuals often have too many assets to qualify for subsidized housing.

Although not considered a housing option, adult day care provides a safe and supportive environment during the day for adults who cannot or choose not to stay alone. This service is often needed for caregivers who work during regular hours or need respite. Socialization, recreational activities, medication supervision, and meals are provided on-site. Often transportation to and from the facility is provided.

Sources of Income

In 2006, the median household income of older adults was $27,798. Aggregate income for the population aged 65 years and over came largely from four sources: Social Security provided 37%, earnings accounted for 28%, pensions provided 18%, and asset income accounted for 15%. Among older Americans in the lowest fifth of the income distribution, Social Security accounts for 83% of aggregate income, and public assistance accounts for another 8%. For those whose income is in the highest income category, Social Security, pensions, and asset income each account for about one fifth of aggregate income, and earnings account for the remaining two fifths (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008).

With aging, a good percentage of income is spent on health care. Most older adults have Medicare, which provides health insurance for those who are 65 years of age or older, disabled, or have end-stage renal disease. Medicare is funded, in part, by Social Security contributions from employers, employees, and the self-employed. Medicare Part A is a hospital insurance plan that covers acute care, short-term rehabilitative care, and some costs associated with hospice and home health care. For 2009, the Part A deductible for acute care was $1068 for the first 60 days of a hospital stay per benefit period. This amount increases for longer hospital stays. Rehabilitative care generally provided in skilled nursing facilities is only covered if it occurs after a 3-day hospital stay and requires “skilled care” provided by a licensed nurse or by a physical or occupational therapist. Medicare Part A will pay 100% of the first 20 days of a nursing home stay, with a daily co-pay for days 21 to 100 and no coverage after that (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS]/Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2006).

Medicare Part B covers the costs for physician and nurse practitioner services; outpatient services, such as diagnostic procedures (e.g., laboratory and x-ray); qualified physical, speech, and occupational therapy; ambulance services; durable medical equipment; and some home health care services. Charges are paid by Medicare at a rate of 80% of what Medicare considers an “allowable charge.” The client is responsible for the remaining 20% of the charge. In addition, the client is responsible for an annual Part B deductible ($135.00 in 2009) and a monthly premium of $96.40. This amount is generally deducted directly from the monthly Social Security check. Most individuals purchase Medigap policies, which cover the deductibles and co-pays. Another option is to join a Medicare Advantage Plan, which often provides more choices and benefits such as extra days in the hospital. To join a Medicare Advantage Plan, an older adult must have Medicare Part A and Part B. In addition to the Part B premium, there may be an additional monthly premium for the extra benefits provided (USDHHS/CMS, 2006).

The newest component of Medicare is the prescription drug coverage that became available in January 2006. The prescription drug plan is designed to help lower prescription drug costs. The individual chooses the drug plan and pays a monthly premium (about $37/month) and an annual deductible ($250 in 2006—this may increase in subsequent years). After the plan participant meets the deductible, he or she is responsible for 25% co-pay up to $2250. The individual is responsible for 100% of the next $2850, or a total out-of-pocket cost of $3600. At that point, the plan will pay 95% of prescription drug costs (USDHHS/CMS, 2006).

For older adults with low incomes, Medicaid may be available to offset the Medicare deductibles and co-pays and to provide additional health benefits. Each state establishes its own eligibility criteria within the broad guidelines established by the federal government. Medicaid generally covers more services than Medicare, including custodial care in nursing homes, without deductibles or co-pays.

Poverty and Health Education

To determine who is considered poor, the U.S. Census Bureau compares family income (or an unrelated individual’s income) with a set of poverty thresholds that vary by family size and composition and are updated annually for inflation. By 2006, the proportion of the older population living in poverty had decreased dramatically to 9%. Older women (12%) were more likely than older men (7%) to live in poverty. Older people who live alone have higher rates of poverty than those who are married. Race and ethnicity are also related to poverty among the older population. In 2006, older whites were far less likely than older blacks and Hispanics to be living in poverty (about 7% compared with 23% and 19%, respectively) (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008).

Community nurses will be increasingly called upon to care for older adults of diverse backgrounds who reside in various living arrangements. Although educational attainment has increased among the elderly population, many older adults have less than a high school education; therefore nurses must be sensitive and creative when providing instruction and teaching. Nurses cannot assume that an older adult has had a formal education. In addition, instructions may need to be given at a slower pace. It may also be imperative to include family or significant others when providing instruction. Also, written information may be sent home for further reference.

On the other hand, increased educational levels of current and future elders also provide a challenge for the community health nurse. These elders are, and will be, more informed and will make greater demands for current and scientifically based information, thus requiring the community health nurse to be knowledgeable about the latest developments in health care. Last, nurses must be aware of community programs and services that address the needs of a diverse older population. Many of these resources are discussed in this chapter.

Psychosocial issues

In addition to adjusting to physiological changes related to aging and health concerns (discussed later in this chapter), older adults must cope with psychosocial and role changes such as retirement, relocation, widowhood, loss of family and friends, and possibly raising their grandchildren. Retirement may be a happy occasion when voluntary; however, the opposite may be true if it is involuntary. When older adults retire, they inevitably must cope with a change in social status and possibly income level; this may be especially difficult for people whose self-concept is related to job status. For retirees who are married, the spouse must also adjust to the changes related to retirement. Indeed, the adjustment may be more difficult for the spouse than the retiree as the retiree’s leisure time will be increased. For elders who have no hobbies or interests, this extra leisure time may be a source of boredom. Nurses should encourage older retirees to pursue old hobbies and interests or establish new ones.

Relocation is another psychosocial issue that many older adults must manage. Often, relocation occurs as a result of health and functional impairment, lack of ability to maintain one’s home, unsafe neighborhoods, and lack of assistance with ADLs or IADLs. The relocation may be prompted by the older adult’s desire to be closer to family or medical care, or interest in moving to a new location or more supportive housing (as discussed in the section Alternative Housing Options for Seniors).

Widowhood is an event experienced by most older adults, especially elderly women. According to Miller (2009), common consequences of widowhood are loss of one’s sexual partner; loss of companionship and intimacy; feelings of grief, loneliness, and emptiness; increased responsibilities and dependency on others; loss of income and less efficient financial management; and changes in relationships with children, married friends, and other family members. Widowhood may be especially traumatic for elders who have been married for many decades. In addition to the loss of a spouse, older adults must also cope with loss of family members (sometimes their own children) and friends.

On the other hand, many older adults are faced with the responsibility of raising their grandchildren. Substantial increases have occurred in the number of children under age 18 years living in households maintained by their grandparents, often without the presence of the grandchildren’s parents. Antecedents to children being raised by grandparents include neglect related to parental substance abuse, abandonment, emotional and physical abuse, parental death, mental and physical illness, incarceration, teen pregnancy, and grandparents assisting adult children who work or attend school. This arrangement may contribute to both physical and psychological problems. For example, Ross and Aday (2006) investigated the degree of stress in 50 African-American grandparents and found that 94% of the grandparents reported a “clinically significant” level of stress. Use of professional counseling, special school programs, and length of care giving greater than 5 years were associated with less stress. From this study it was noted that coping strategies that were significantly correlated with less stress included accepting responsibility, confrontive coping, self-control, positive reappraisal, planful problem solving, and distancing.

The role of the community health nurse is to identify, support, and assist older adults experiencing various psychosocial changes and role adjustments. In addition, the nurse should provide information about various community resources and make referrals to agencies that might be helpful.

Physiological changes

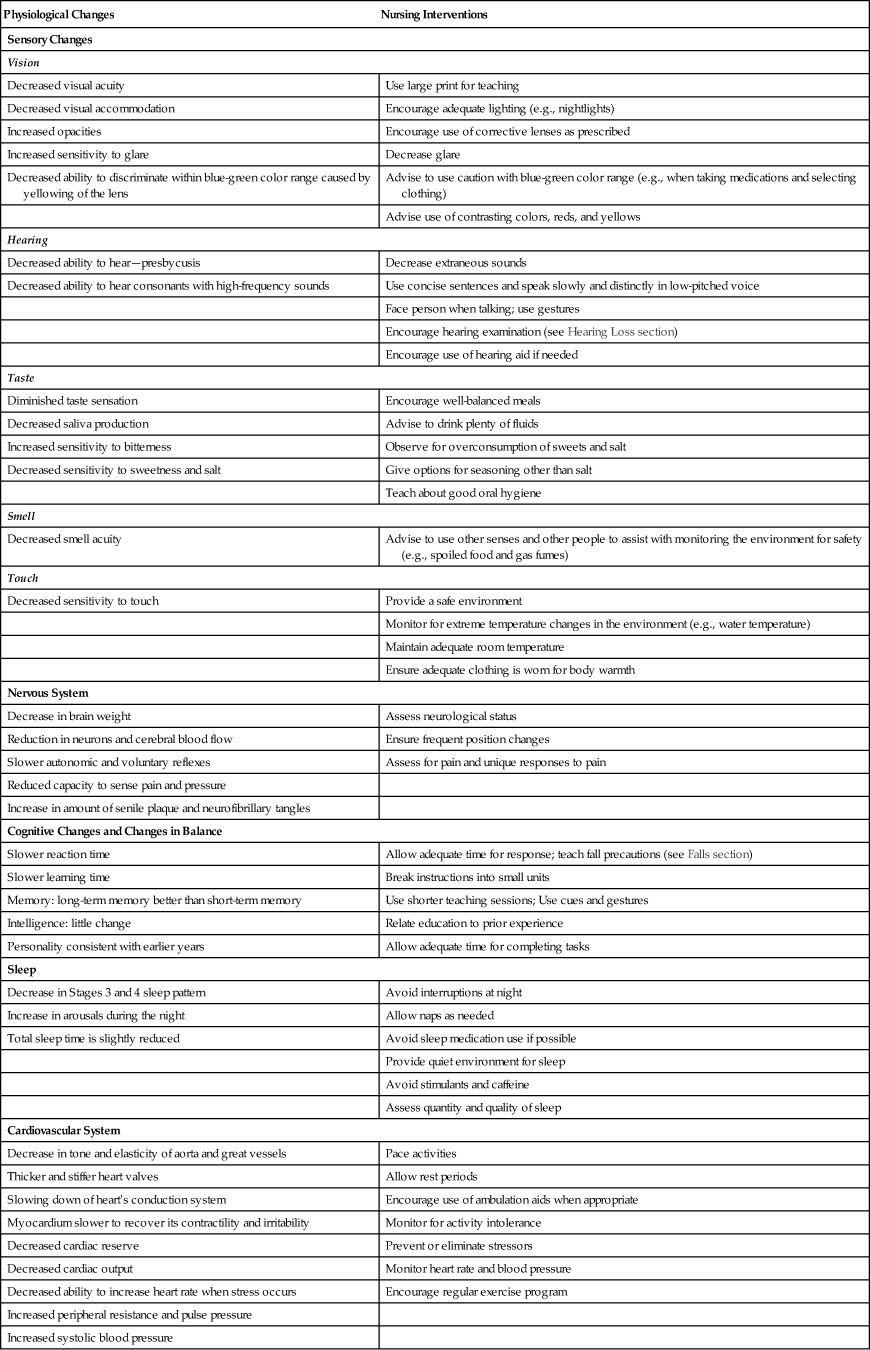

Normal physiological aging changes occur in all body systems. However, it is important to note that the rate and degree of these changes are highly individualized. These changes are influenced by genetic factors, diet, exercise, the environment, health status, stress, lifestyle choices, and many other elements. Table 19-1 depicts common physiological changes that occur with aging.

TABLE 19-1

Normal Physiological Changes Associated with Aging

| Physiological Changes | Nursing Interventions |

| Sensory Changes | |

| Vision | |

| Decreased visual acuity | Use large print for teaching |

| Decreased visual accommodation | Encourage adequate lighting (e.g., nightlights) |

| Increased opacities | Encourage use of corrective lenses as prescribed |

| Increased sensitivity to glare | Decrease glare |

| Decreased ability to discriminate within blue-green color range caused by yellowing of the lens | Advise to use caution with blue-green color range (e.g., when taking medications and selecting clothing) |

| Advise use of contrasting colors, reds, and yellows | |

| Hearing | |

| Decreased ability to hear—presbycusis | Decrease extraneous sounds |

| Decreased ability to hear consonants with high-frequency sounds | Use concise sentences and speak slowly and distinctly in low-pitched voice |

| Face person when talking; use gestures | |

| Encourage hearing examination (see Hearing Loss section) | |

| Encourage use of hearing aid if needed | |

| Taste | |

| Diminished taste sensation | Encourage well-balanced meals |

| Decreased saliva production | Advise to drink plenty of fluids |

| Increased sensitivity to bitterness | Observe for overconsumption of sweets and salt |

| Decreased sensitivity to sweetness and salt | Give options for seasoning other than salt |

| Teach about good oral hygiene | |

| Smell | |

| Decreased smell acuity | Advise to use other senses and other people to assist with monitoring the environment for safety (e.g., spoiled food and gas fumes) |

| Touch | |

| Decreased sensitivity to touch | Provide a safe environment |

| Monitor for extreme temperature changes in the environment (e.g., water temperature) | |

| Maintain adequate room temperature | |

| Ensure adequate clothing is worn for body warmth | |

| Nervous System | |

| Decrease in brain weight | Assess neurological status |

| Reduction in neurons and cerebral blood flow | Ensure frequent position changes |

| Slower autonomic and voluntary reflexes | Assess for pain and unique responses to pain |

| Reduced capacity to sense pain and pressure | |

| Increase in amount of senile plaque and neurofibrillary tangles | |

| Cognitive Changes and Changes in Balance | |

| Slower reaction time | Allow adequate time for response; teach fall precautions (see Falls section) |

| Slower learning time | Break instructions into small units |

| Memory: long-term memory better than short-term memory | Use shorter teaching sessions; Use cues and gestures |

| Intelligence: little change | Relate education to prior experience |

| Personality consistent with earlier years | Allow adequate time for completing tasks |

| Sleep | |

| Decrease in Stages 3 and 4 sleep pattern | Avoid interruptions at night |

| Increase in arousals during the night | Allow naps as needed |

| Total sleep time is slightly reduced | Avoid sleep medication use if possible |

| Provide quiet environment for sleep | |

| Avoid stimulants and caffeine | |

| Assess quantity and quality of sleep | |

| Cardiovascular System | |

| Decrease in tone and elasticity of aorta and great vessels | Pace activities |

| Thicker and stiffer heart valves | Allow rest periods |

| Slowing down of heart’s conduction system | Encourage use of ambulation aids when appropriate |

| Myocardium slower to recover its contractility and irritability | Monitor for activity intolerance |

| Decreased cardiac reserve | Prevent or eliminate stressors |

| Decreased cardiac output | Monitor heart rate and blood pressure |

| Decreased ability to increase heart rate when stress occurs | Encourage regular exercise program |

| Increased peripheral resistance and pulse pressure | |

| Increased systolic blood pressure | |

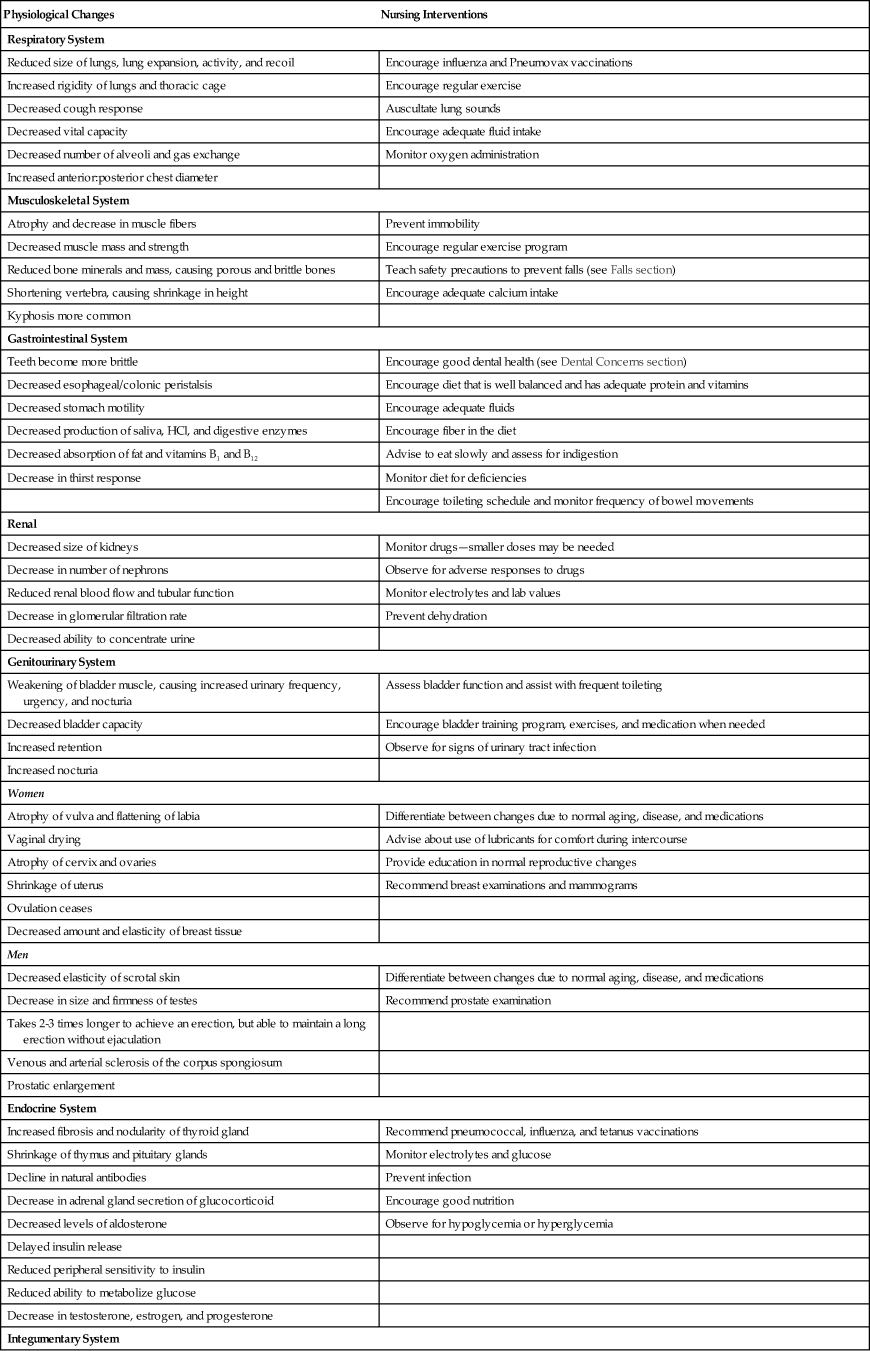

| Respiratory System | |

| Reduced size of lungs, lung expansion, activity, and recoil | Encourage influenza and Pneumovax vaccinations |

| Increased rigidity of lungs and thoracic cage | Encourage regular exercise |

| Decreased cough response | Auscultate lung sounds |

| Decreased vital capacity | Encourage adequate fluid intake |

| Decreased number of alveoli and gas exchange | Monitor oxygen administration |

| Increased anterior:posterior chest diameter | |

| Musculoskeletal System | |

| Atrophy and decrease in muscle fibers | Prevent immobility |

| Decreased muscle mass and strength | Encourage regular exercise program |

| Reduced bone minerals and mass, causing porous and brittle bones | Teach safety precautions to prevent falls (see Falls section) |

| Shortening vertebra, causing shrinkage in height | Encourage adequate calcium intake |

| Kyphosis more common | |

| Gastrointestinal System | |

| Teeth become more brittle | Encourage good dental health (see Dental Concerns section) |

| Decreased esophageal/colonic peristalsis | Encourage diet that is well balanced and has adequate protein and vitamins |

| Decreased stomach motility | Encourage adequate fluids |

| Decreased production of saliva, HCl, and digestive enzymes | Encourage fiber in the diet |

| Decreased absorption of fat and vitamins B1 and B12 | Advise to eat slowly and assess for indigestion |

| Decrease in thirst response | Monitor diet for deficiencies |

| Encourage toileting schedule and monitor frequency of bowel movements | |

| Renal | |

| Decreased size of kidneys | Monitor drugs—smaller doses may be needed |

| Decrease in number of nephrons | Observe for adverse responses to drugs |

| Reduced renal blood flow and tubular function | Monitor electrolytes and lab values |

| Decrease in glomerular filtration rate | Prevent dehydration |

| Decreased ability to concentrate urine | |

| Genitourinary System | |

| Weakening of bladder muscle, causing increased urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia | Assess bladder function and assist with frequent toileting |

| Decreased bladder capacity | Encourage bladder training program, exercises, and medication when needed |

| Increased retention | Observe for signs of urinary tract infection |

| Increased nocturia | |

| Women | |

| Atrophy of vulva and flattening of labia | Differentiate between changes due to normal aging, disease, and medications |

| Vaginal drying | Advise about use of lubricants for comfort during intercourse |

| Atrophy of cervix and ovaries | Provide education in normal reproductive changes |

| Shrinkage of uterus | Recommend breast examinations and mammograms |

| Ovulation ceases | |

| Decreased amount and elasticity of breast tissue | |

| Men | |

| Decreased elasticity of scrotal skin | Differentiate between changes due to normal aging, disease, and medications |

| Decrease in size and firmness of testes | Recommend prostate examination |

| Takes 2-3 times longer to achieve an erection, but able to maintain a long erection without ejaculation | |

| Venous and arterial sclerosis of the corpus spongiosum | |

| Prostatic enlargement | |

| Endocrine System | |

| Increased fibrosis and nodularity of thyroid gland | Recommend pneumococcal, influenza, and tetanus vaccinations |

| Shrinkage of thymus and pituitary glands | Monitor electrolytes and glucose |

| Decline in natural antibodies | Prevent infection |

| Decrease in adrenal gland secretion of glucocorticoid | Encourage good nutrition |

| Decreased levels of aldosterone | Observe for hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia |

| Delayed insulin release | |

| Reduced peripheral sensitivity to insulin | |

| Reduced ability to metabolize glucose | |

| Decrease in testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone | |

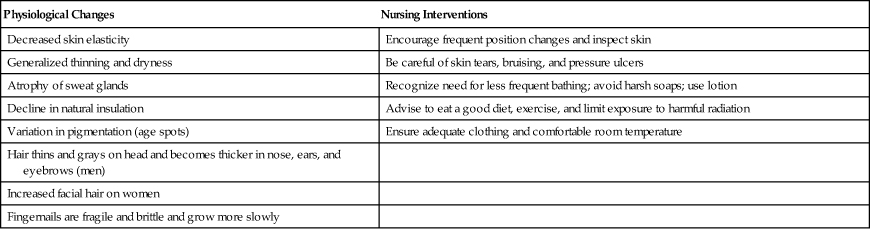

| Integumentary System | |

| Decreased skin elasticity | Encourage frequent position changes and inspect skin |

| Generalized thinning and dryness | Be careful of skin tears, bruising, and pressure ulcers |

| Atrophy of sweat glands | Recognize need for less frequent bathing; avoid harsh soaps; use lotion |

| Decline in natural insulation | Advise to eat a good diet, exercise, and limit exposure to harmful radiation |

| Variation in pigmentation (age spots) | Ensure adequate clothing and comfortable room temperature |

| Hair thins and grays on head and becomes thicker in nose, ears, and eyebrows (men) | |

| Increased facial hair on women | |

| Fingernails are fragile and brittle and grow more slowly | |

From Eliopoulos C: Gerontological nursing, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2010, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Wellness and health promotion

Health promotion and illness prevention interventions for older adults may be beneficial in reducing death and disability and improving quality of life. These are goals of Healthy People 2020. To address these goals, health care professionals must inform and educate elders about the benefits of health care screenings and examinations, physical activity and fitness, and good nutrition.

Healthy People 2020

A primary goal of Healthy People 2020 is to increase the quality and years of healthy life. Although people are living longer, many older adults have chronic illnesses that interfere with the quality of their lives. To address this issue, Healthy People 2020 includes specific objectives related to increasing health promotion programs and decreasing morbidity and mortality in older adults.

Recommended Health Care Screenings and Examinations

Many organizations such as the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association, and the USDHHS Preventive Services Task Force have established recommendations for health promotion screenings and examinations. Box 19-2 depicts some of the more widely agreed-on screenings and examinations for older adults. These established recommendations might be very useful to community nurses when educating older adults about the benefits of screening and early detection of disease. Frequently, earlier detection of disease allows better treatment, lower health care costs, and the possibility of cure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020