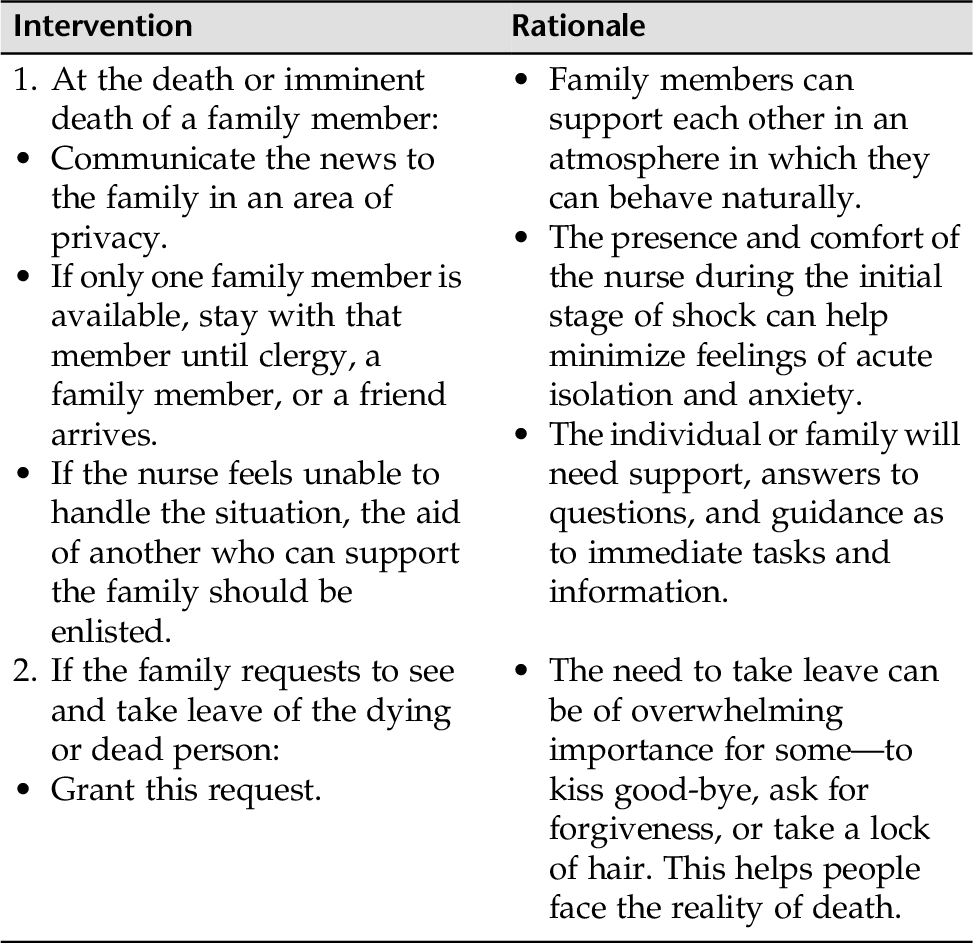

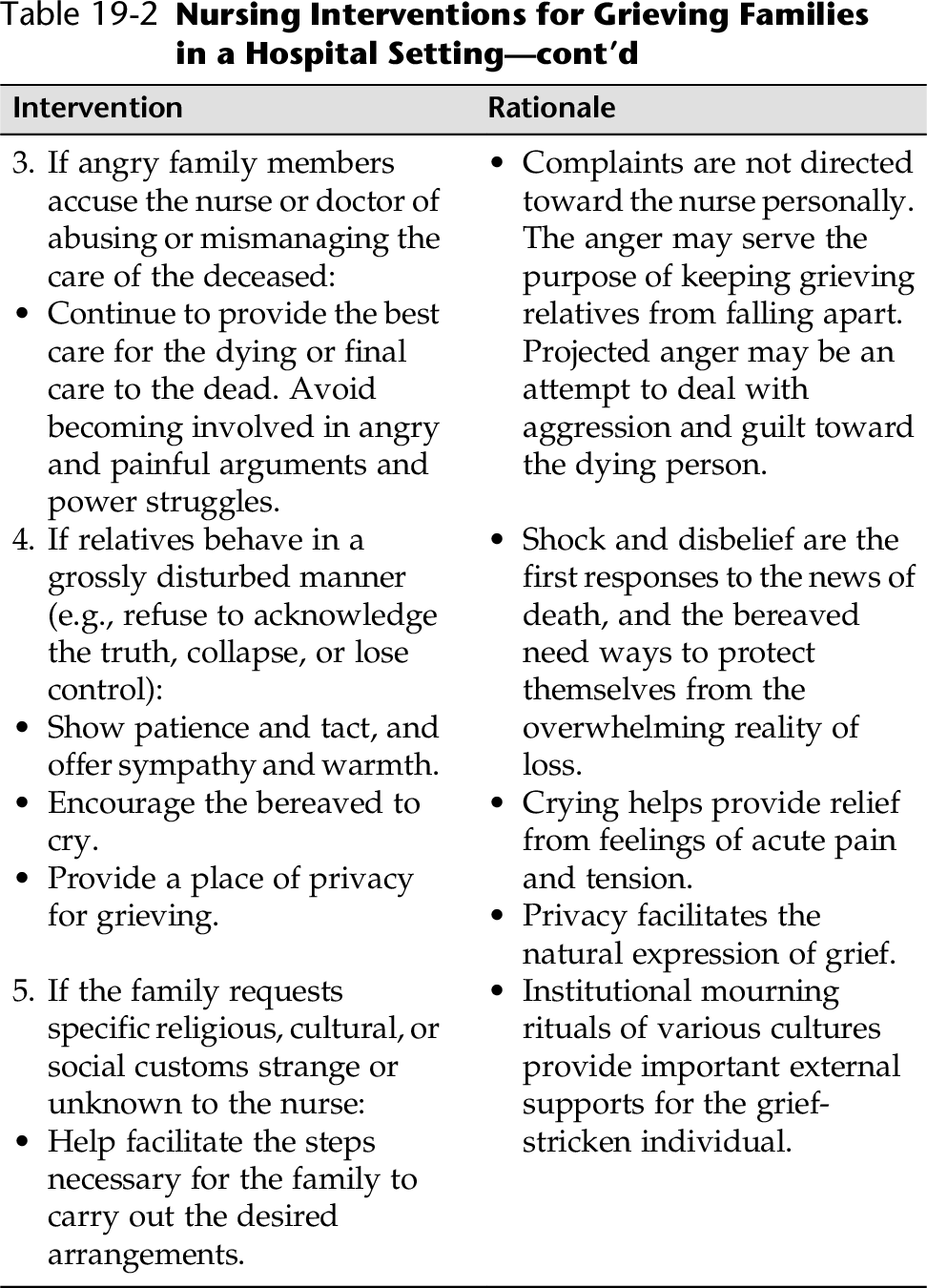

CHAPTER 19 Loss is part of the human experience, and grief and mourning are painful although normal responses to loss. We grieve on a recurring basis as we face the commonplace losses in our lives, whether it is loss of a relationship (divorce, separation, death, abortion), health (a body function or part, mental or physical capacity), friendship, status, prestige, or security (occupational, financial, social). Other losses may be more intangible such as loss of self-confidence, self-concept, or the loss of future dreams. Loss through a significant death is a major life crisis for most people. Grief is the characteristic painful feelings precipitated by the death of a loved one or by some other significant loss. Grief is nearly universal, and it expresses itself in many different ways. For example, frequent crying spells, depressed mood, sleep disturbances, and loss of appetite are common during the bereavement process. Mourning refers to all the ways a person experiences grief on the outside. This includes culturally determined practices such as wakes, funerals, sitting Shiva, or decorating the gravesite, which are all ethnic, cultural, spiritual, and religious expressions of going through the grief process. According to Kramer-Howe, “understanding how to support healthy mourning in oneself and others is a vital life skill and can even be regarded as a public health issue” Kramer-Howe (2013). Bereavement is the complex process during the period of grief and mourning. During this time, people often experience fluctuating thoughts that occur in intense waves. We know from our own experience that significant losses are never forgotten. As time goes on, the painful feelings become less intense and more manageable (Harvard Mental Health Letter, 2011). “Normal” grief reaction includes a number of phenomena that can last from 6 to 12 months. Box 19-1 lists some of these “normal” grief reactions. Most bereaved persons experience a “normal” grief reaction and resolve their loss with help and support from family and friends. However, some individuals may experience complicated grief and may require professional support. Acute grief can trigger an exacerbation of any preexisting medical or psychological problems. A history of depression, substance abuse, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can complicate grief and require treatment. Unresolved grief reactions account for many of the physical symptoms seen in medical clinics and hospital units. Suicide is higher among individuals who have had a significant loss, especially if losses are multiple, and/or grieving mechanisms are limited. The death of a child, a violent death, and multiple deaths are regarded as the most severe types of loss. Complicated grieving can be a problem, and in that case interventions are appropriate. Individuals will react within their own cultural patterns and value and personality structure, as well as within their own social environment. Most of us are programmed in our response to death. Distinct characteristics, however, can be identified throughout the grieving process. Refer to Table 19-1 for some indications that a grief reaction is extreme and may warrant intervention. Table 19-1 Potential Symptoms of Complicated Grief Nurses are not immune to grief reactions. As health care workers, as nurses, as friends, as people who will experience grief and loss throughout our own lifetimes, it is helpful to know what happens during the process of mourning, what might help others through this process, and how to identify an individual who is having difficulty resolving his or her pain and sorrow (complicated grieving). Most nurses and clinicians are familiar with Kübler-Ross’s (1969) classic review of the stages of death and dying (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance). However, it does not reflect what individuals actually experience while mourning in terms of going through each stage in order, intensity, duration, and so on. “In reality, each person’s experience of grief is unique to the person to the relationship he or she had with a loved one to the way that happened to the person’s prior history with major losses, and to current like circumstances” (Kramer-Howe, 2013). There is no particular path or “right way to grieve.” Every person and every family grieves differently, and each person and each family needs to find their own unique path to finding a meaningful way to come to terms with their loss. Unfortunately, some health care workers rush to start medications as soon as the griever starts to exhibit expected symptoms such as not wanting to eat, difficulty sleeping, and so on. Depression is a normal part of mourning and should not be confused with a mental health disorder. Nurses can help bereaved individuals by listening, assisting in communication, teaching families about the process of dying, or facilitating bereavement with opportunities to prevent ill health and to help families find new directions for growth. Nurses come in contact with bereaved individuals and families in all hospital and clinic settings. It is helpful for all nurses to understand the complex process of grieving so they can differentiate normal grief from complicated grief. Offering information to the bereaved individual about useful and appropriate responses and suggesting resources that might help him or her through the grieving process can also broaden an understanding of ourselves. We all experience loss throughout our lives. • Was the bereaved heavily dependent on the deceased? • Were there persistent, unresolved conflicts with the deceased? • Was the deceased a child (often the most profound loss)? • Does the bereaved have a meaningful relationship/support system? • Has the bereaved experienced a number of previous losses? • Does the bereaved have sound coping skills? • Was the deceased’s death associated with a cultural stigma (e.g., AIDS, suicide)? • Was the death unexpected or associated with violence (murder, suicide)? • Has the bereaved had difficulty resolving past significant losses? • Does the bereaved have a history of depression, drug or alcohol abuse, or other psychiatric illness? • If the bereaved is young, are there indications for special interventions? • Prolonged, severe symptoms lasting for 2 to 6 months or longer • Limited response to support • Profound and persistent feelings of hopelessness • Completely withdrawn or fears being alone • Inability to work; create; or feel emotion and positive states of mind for long periods of time • Maladaptive behaviors in response to the death, for example: • Promiscuity • Fugue states • Feeling dead or unreal • Suicidal ideation • Aggressive behaviors • Compulsive spending • Recurrent nightmares, night terrors, compulsive reenactments • Exhaustion from lack of sleep and hyperarousal • Prolonged depression, panic attacks • Self neglect Box 19-1 and Table 19-1 present normal phenomena observed during normal mourning and those that might alert others to a complicated grief reaction. This can be used as a helpful guide in your assessment. 1. Identify if the individual is at risk for complicated grieving (see Assessing History). 2. Evaluate for psychotic symptoms, agitation, increased activity, alcohol/drug abuse, and extreme vegetative symptoms (anorexia, weight loss, not sleeping). 3. Do not overlook people who do not express significant grief in the context of a major loss. Those individuals might have an increased risk of subsequent complicated or unresolved grief reaction (Kaplan & Sadock, 2007). 4. Complicated grief reactions require significant interventions. Suicidal or severely depressed individuals might require hospitalization. Always assess for suicide with signs of depression or other dysfunctional signs or symptoms. 5. Assess support systems. If support systems are limited, find bereavement groups in the bereaved individual’s community. 6. When grieving is stalled or complicated, a variety of therapeutic approaches have proved extremely beneficial (e.g., cognitive-behavioral interventions). Provide referrals. 7. Grieving can bring with it severe spiritual anguish. Would spiritual counseling or a specific counselor be useful for the bereaved at this time? The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA International, 2012-2014) identifies three nursing diagnoses for nursing actions: Grieving, Complicated Grieving, and Risk for Complicated Grieving. Nurses are in constant contact with people and their families experiencing painful losses, and an acute grief reaction may also be the focus of treatment. During this time, the nurse might need to intervene for Ineffective Coping or Compromised Family Coping, Disturbed Sleep Pattern, Risk for Spiritual Distress or Spiritual Distress, or other problems. • Be there for the bereaved; give your full presence. • Offer physical touch suited to the moment and your relationship. Do not use touch if it will presume an intimacy that does not exist or as a tool to coerce a person to mourn. • Identify family or friends to assist with practical concerns. • Try to provide beauty or nourishment in some suitable form. • Encourage the individual and family to mourn on their own schedule. 2. Identify and treat/refer an individual with a pathological process. 3. Assess for suicide if there is persistent, severe depression and deep, enduring feelings of hopelessness. 4. Know, share, and support with the bereaved the normal phenomena that occur during the normal mourning process, which might concern some individuals (e.g., intense anger at the deceased, guilt, symptoms the deceased had before death, unbidden flood of memories). Give the bereaved a written handout for reference. 5. When the family member dies in the hospital, apply appropriate measures that can help facilitate grieving for families (Table 19-2).

Grieving and Complicated Grieving

OVERVIEW

Initial response to the death

Avoidant; overwhelmed, dazed, confused; self-punitive; inappropriately hostile

Response to the death

Panic; dissociative reactions, reactive psychoses

Extreme use of denial

Maladaptive avoidances confronting the implications of death: drug or alcohol abuse, counterphobic frenzy, promiscuity, fugue states, phobic avoidance, feeling dead or unreal

Extreme experiences of intrusion

Flooding with negative images and emotions; uncontrolled ideation; self-impairing compulsive reenactments; night terrors, recurrent nightmares; distraught from intrusion of anger, anxiety, despair, shame, or guilt themes; physiological exhaustion from hyperarousal

Progression through the process of mourning

The sense that one cannot integrate the death with a sense of self and continued life. Persistent, warded-off themes can manifest as anxious, depressed, enraged, shame-filled, or guilty moods and psychophysiological syndromes.

Inability to reorganize one’s life and resolve the process of mourning

Failure to complete mourning might be associated with inability to work; create; feel emotion; or experience positive states of mind

ASSESSMENT

Assessing for Signs and Symptoms of Complicated Grief

Presenting Signs and Symptoms of Complicated Grief

Assessment Tools

Assessment Guidelines

Grieving and Complicated Grieving

NURSING DIAGNOSES WITH INTERVENTIONS

Discussion of Potential Nursing Diagnoses

Overall Guidelines for Nursing Interventions

Grieving and Complicated Grieving

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree