Care of Patients with Hypertension and Peripheral Vascular Disease

Objectives

1. Diagram the pathophysiology of hypertension.

2. Predict the complications that can occur as a consequence of hypertension.

3. Briefly describe the treatment program for mild, moderate, and severe hypertension.

4. Contrast the pathophysiology of arteriosclerosis with that of atherosclerosis.

5. Review four factors that contribute to peripheral vascular disease.

6. Recognize the signs, symptoms, and treatment of aneurysm.

7. Prepare a teaching plan for a patient with Raynaud’s syndrome.

8. Compare the etiology and care for thrombophlebitis and deep vein thrombosis.

9. Summarize how venous insufficiency may lead to a venous stasis ulcer.

10. Compare venous stasis ulcer with arterial leg ulcer.

11. List types of surgery performed for problems of the peripheral vascular system.

1. Develop and implement a teaching plan for a patient who has hypertension.

3. Institute a teaching plan for the patient undergoing anticoagulant therapy.

4. Differentiate between venous and arterial insufficiency during a physical assessment.

5. Prepare a nursing care plan for the patient with arterial insufficiency.

Key Terms

bruit (BRŬ-ē, p. 413)

embolus (ĔM-bō-lŭs, p. 406)

gangrene (găng-GRĒN, p. 413)

hypertension (p. 398)

intermittent claudication (ĭn-tĕr-MĬT-ĕnt klăw-dĭ-KĂ-shŭn, p. 407)

rubor (RŪ-bōr, p. 407)

scleropathy (sklĕr-ŎP-ă-thē, p. 420)

stent (p. 409)

thrombophlebitis (thrŏm-bō-flĕ-BĪ-tĭs, p. 406)

thrombus (THRŎM-bŭs, p. 409)

varicose veins (VĂR-ĭ-kōs vānz, p. 416)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

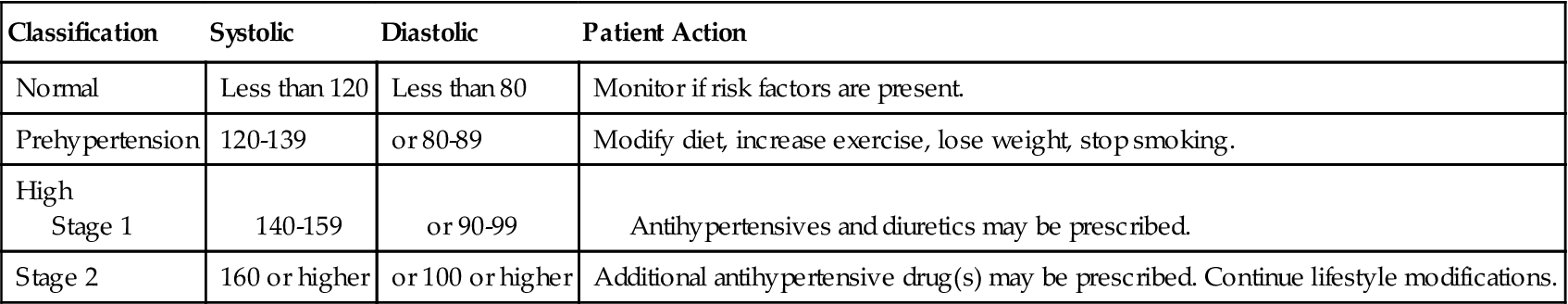

Hypertension

Hypertension is defined as persistently high blood pressure. This means a systolic pressure that is equal to or greater than 140 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure that is equal to or greater than 90 mm Hg when taken at least twice and averaged on two different occasions 2 weeks apart. The diastolic pressure is the main focus of treatment. It reflects the amount of pressure being exerted against the vessel walls while the heart is in its phase of relaxation and there is no added pressure from blood being forced out of the left ventricle and into the arteries. Table 19-1 presents ranges for the classification of hypertension.

Table 19-1

| Classification | Systolic | Diastolic | Patient Action |

| Normal | Less than 120 | Less than 80 | Monitor if risk factors are present. |

| Prehypertension | 120-139 | or 80-89 | Modify diet, increase exercise, lose weight, stop smoking. |

| High Stage 1 | 140-159 | or 90-99 | Antihypertensives and diuretics may be prescribed. |

| Stage 2 | 160 or higher | or 100 or higher | Additional antihypertensive drug(s) may be prescribed. Continue lifestyle modifications. |

Hypertensive individuals usually die of long-term damage to the end organs or target organs, that is, from damage to the brain, heart, and kidney. More than half the deaths associated with persistent and unrelieved hypertension are caused by myocardial infarction. Immediate causes of death related to high blood pressure include cerebral hemorrhage and heart failure.

Etiology

The etiology of hypertension is unknown, but there are several contributing factors. Secretion of excess sodium-retaining hormones and vasoconstriction substances, high sodium intake, obesity, diabetes mellitus, excessive alcohol intake, and sympathetic nervous system activity all contribute to elevated blood pressure.

There are two major types of hypertension: primary (idiopathic or essential) and secondary hypertension. Persons with a family history of hypertension are at risk for developing primary hypertension. Approximately 90% to 95% of all cases of hypertension are primary.

In 5% to 8% the hypertension is secondary to another disorder. Acute stress, excessive alcohol intake, sickle cell disease, arteriosclerosis, coarctation of the aorta, eclampsia of pregnancy, renal disorders, endocrine disorders, and neurologic disorders are examples of secondary causes. Amphetamine use, chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, and tyramine-containing foods such as beer and wine taken with monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors contribute to secondary hypertension. Female hormone therapy and nicotine use appear to be contributing factors in some people. If the underlying disorder can be detected and treated successfully, the problem of secondary hypertension is eliminated or more easily controlled. If no underlying disease can be identified as elevating the patient’s blood pressure, the patient is said to have primary hypertension.

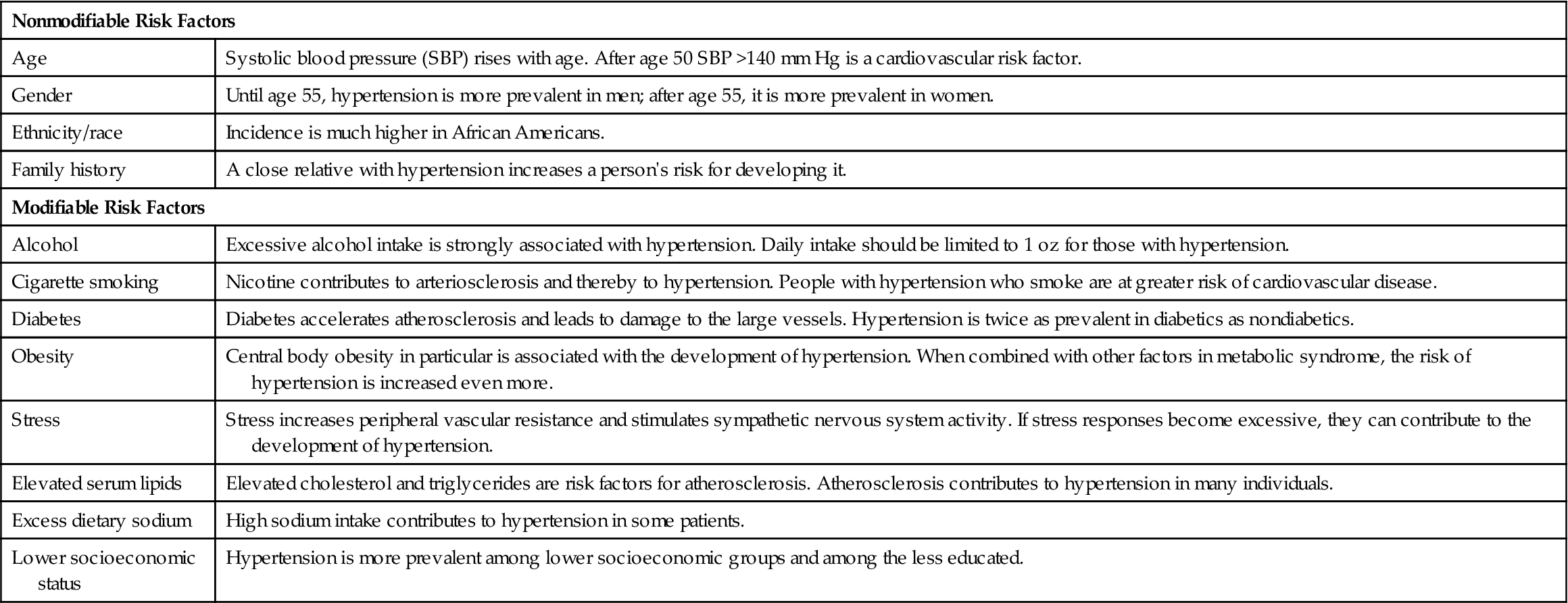

Table 19-2 presents the nonmodifiable and modifiable risk factors for hypertension. Many times a loss of excess weight alone can return a slightly elevated blood pressure to normal. A moderate reduction of salt intake has been effective in lowering the blood pressure of some persons with mild or moderate hypertension. There is continuing research on the relationship of race, gender, and ethnicity on the incidence and effects of hypertension.

Table 19-2

Nonmodifiable and Modifiable Risk Factors for Primary Hypertension

| Nonmodifiable Risk Factors | |

| Age | Systolic blood pressure (SBP) rises with age. After age 50 SBP >140 mm Hg is a cardiovascular risk factor. |

| Gender | Until age 55, hypertension is more prevalent in men; after age 55, it is more prevalent in women. |

| Ethnicity/race | Incidence is much higher in African Americans. |

| Family history | A close relative with hypertension increases a person’s risk for developing it. |

| Modifiable Risk Factors | |

| Alcohol | Excessive alcohol intake is strongly associated with hypertension. Daily intake should be limited to 1 oz for those with hypertension. |

| Cigarette smoking | Nicotine contributes to arteriosclerosis and thereby to hypertension. People with hypertension who smoke are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease. |

| Diabetes | Diabetes accelerates atherosclerosis and leads to damage to the large vessels. Hypertension is twice as prevalent in diabetics as nondiabetics. |

| Obesity | Central body obesity in particular is associated with the development of hypertension. When combined with other factors in metabolic syndrome, the risk of hypertension is increased even more. |

| Stress | Stress increases peripheral vascular resistance and stimulates sympathetic nervous system activity. If stress responses become excessive, they can contribute to the development of hypertension. |

| Elevated serum lipids | Elevated cholesterol and triglycerides are risk factors for atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis contributes to hypertension in many individuals. |

| Excess dietary sodium | High sodium intake contributes to hypertension in some patients. |

| Lower socioeconomic status | Hypertension is more prevalent among lower socioeconomic groups and among the less educated. |

The rising incidence of childhood obesity has resulted in an increase in the incidence of hypertension. Health promotion activities targeting nutrition and exercise habits of children are increasing.

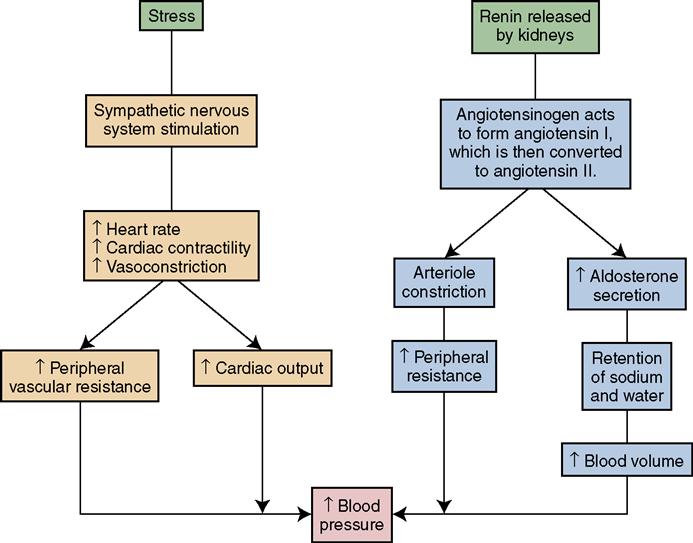

Pathophysiology

Blood pressure equals the amount of blood pumped out of the heart multiplied by the systemic vascular resistance. If the diameter of blood vessels becomes smaller because of atherosclerosis or vasoconstriction, blood pressure increases in an effort to force the blood through the smaller opening. If there is an increase in the volume (amount) or viscosity (thickness or consistency) of fluid in the blood vessels, the pressure within the vessels increases and the heart must work harder to pump the fluid through the vessels. A pathologic response to stress can result in an elevation in blood pressure by stimulating the sympathetic nervous system and causing peripheral vasoconstriction and increased heart rate.

Insulin, glucose, and lipoprotein abnormalities are common in primary hypertension. High blood insulin concentration stimulates sympathetic nervous system activity contributing to vasoconstriction.

In some instances of hypertension, an excess of renin is secreted by the kidneys. Renin acts on a substance called angiotensinogen, converting it to angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is converted to angiotensin II by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). Angiotensin II acts directly on the blood vessels, causing them to constrict, and stimulates the adrenal gland to release aldosterone. Angiotensin thereby increases resistance to blood flow in the peripheral vessels and causes retention of sodium and water by the renal tubules through the influence of aldosterone (see Figure 18-6). The retained sodium and water increase the blood volume, causing increased cardiac output and elevation of blood pressure. Concept Map 19-1 shows the pathophysiology of hypertension.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

Hypertension has been called the “silent killer” because in early stages it does not usually cause discomfort or any other subjective signs and symptoms to indicate its presence. About one third of those who have hypertension are not aware of it. Signs may appear only in the later stages when damage has been done to the target organs—that is, the kidney (renal ischemia and nephrosclerosis), brain (arteriosclerosis and microaneurysms), aorta (aortic aneurysm), eyes (retinal damage), and heart (left ventricular hypertrophy and reduced cardiac output). Patients with symptoms may complain of headache, dizziness, blurred vision, blackouts, irritability, angina, dyspnea, or fatigue.

Hypertensive patients develop coronary heart disease at a rate two to three times greater than that of persons with normal blood pressure. Examination of the blood vessels of the retina will reveal any damage to the retinal vessels. This retinal assessment gives an indication about how much damage the high blood pressure has done to vessels throughout the body. If retinal damage has occurred, it is an indication that the person’s hypertension is moderate to severe.

Diagnosis is by blood pressure readings on at least two occasions 2 weeks apart. An electrocardiogram (ECG) and cardiac stress test may be ordered to determine whether any damage has been done to the coronary arteries or to the heart muscle.

Treatment

The goals of treatment are (1) reduction of high blood pressure and (2) long-term control to decrease the risk of stroke, heart attack, loss of vision, and kidney disease. The target is to control blood pressure at or below 120/80 mm Hg. Treatment is individualized, using a stepped-care approach. For mild hypertension, smoking cessation, weight reduction, sodium restriction, alcohol restriction, exercise, a low-fat diet, and stress control are instituted. Sodium should be kept to less than 2400 mg/day with the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) eating plan. Alcohol intake should not exceed one serving of liquor, wine, or beer for women per day or two servings for men per day. Aerobic exercise of 30 to 45 minutes most days of the week is recommended. If blood pressure is still high, a diuretic is added. If the blood pressure does not fall within normal limits, the second step is initiated, and an antihypertensive drug is prescribed.

Other drugs are added, if needed, to keep the blood pressure consistently within normal limits. Patients with more severe hypertension often require more than two drugs to attain control. The third step is to add additional drugs. The dose of each drug is increased as needed to achieve the desired blood pressure level unless side effects occur. In the event of side effects, another drug is substituted. Newer blood pressure medications are very expensive, and cost is a concern for many patients. Some drug companies have programs to help patients who cannot afford their medications. If a potassium-wasting diuretic is prescribed, the patient is taught to increase the potassium intake. A potassium supplement is added to treatment, and electrolyte levels are monitored regularly.

Patients should monitor their blood pressure at home and keep records of the readings. Periodic visits to the physician’s office for regular examinations are necessary. The better the blood pressure is controlled and kept within normal limits, the less damage there will be to the target organs.

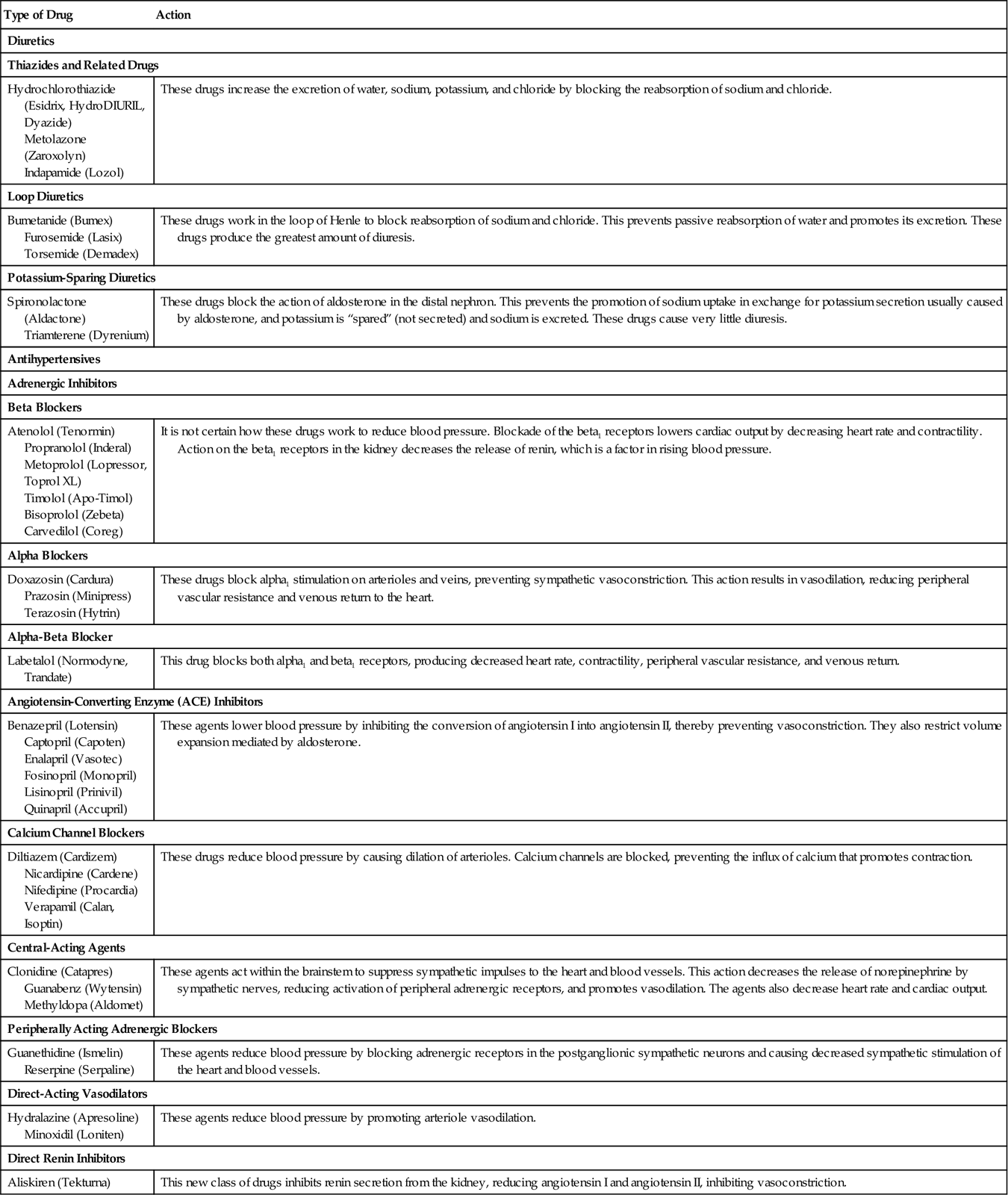

Antihypertensive Therapy

The drugs prescribed to reduce blood pressure work by decreasing blood volume, cardiac output, or peripheral resistance. Table 19-3 and Box 19-1 list examples of the drugs most commonly prescribed for hypertension and relevant nursing interventions.

Table 19-3

Table 19-3

Drug Classifications Used for Patients with Vascular Disorders

| Type of Drug | Action |

| Diuretics | |

| Thiazides and Related Drugs | |

| Hydrochlorothiazide (Esidrix, HydroDIURIL, Dyazide) Metolazone (Zaroxolyn) Indapamide (Lozol) | These drugs increase the excretion of water, sodium, potassium, and chloride by blocking the reabsorption of sodium and chloride. |

| Loop Diuretics | |

| Bumetanide (Bumex) Furosemide (Lasix) Torsemide (Demadex) | These drugs work in the loop of Henle to block reabsorption of sodium and chloride. This prevents passive reabsorption of water and promotes its excretion. These drugs produce the greatest amount of diuresis. |

| Potassium-Sparing Diuretics | |

| Spironolactone (Aldactone) Triamterene (Dyrenium) | These drugs block the action of aldosterone in the distal nephron. This prevents the promotion of sodium uptake in exchange for potassium secretion usually caused by aldosterone, and potassium is “spared” (not secreted) and sodium is excreted. These drugs cause very little diuresis. |

| Antihypertensives | |

| Adrenergic Inhibitors | |

| Beta Blockers | |

| Atenolol (Tenormin) Propranolol (Inderal) Metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol XL) Timolol (Apo-Timol) Bisoprolol (Zebeta) Carvedilol (Coreg) | It is not certain how these drugs work to reduce blood pressure. Blockade of the beta1 receptors lowers cardiac output by decreasing heart rate and contractility. Action on the beta1 receptors in the kidney decreases the release of renin, which is a factor in rising blood pressure. |

| Alpha Blockers | |

| Doxazosin (Cardura) Prazosin (Minipress) Terazosin (Hytrin) | These drugs block alpha1 stimulation on arterioles and veins, preventing sympathetic vasoconstriction. This action results in vasodilation, reducing peripheral vascular resistance and venous return to the heart. |

| Alpha-Beta Blocker | |

| Labetalol (Normodyne, Trandate) | This drug blocks both alpha1 and beta1 receptors, producing decreased heart rate, contractility, peripheral vascular resistance, and venous return. |

| Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors | |

| Benazepril (Lotensin) Captopril (Capoten) Enalapril (Vasotec) Fosinopril (Monopril) Lisinopril (Prinivil) Quinapril (Accupril) | These agents lower blood pressure by inhibiting the conversion of angiotensin I into angiotensin II, thereby preventing vasoconstriction. They also restrict volume expansion mediated by aldosterone. |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | |

| Diltiazem (Cardizem) Nicardipine (Cardene) Nifedipine (Procardia) Verapamil (Calan, Isoptin) | These drugs reduce blood pressure by causing dilation of arterioles. Calcium channels are blocked, preventing the influx of calcium that promotes contraction. |

| Central-Acting Agents | |

| Clonidine (Catapres) Guanabenz (Wytensin) Methyldopa (Aldomet) | These agents act within the brainstem to suppress sympathetic impulses to the heart and blood vessels. This action decreases the release of norepinephrine by sympathetic nerves, reducing activation of peripheral adrenergic receptors, and promotes vasodilation. The agents also decrease heart rate and cardiac output. |

| Peripherally Acting Adrenergic Blockers | |

| Guanethidine (Ismelin) Reserpine (Serpaline) | These agents reduce blood pressure by blocking adrenergic receptors in the postganglionic sympathetic neurons and causing decreased sympathetic stimulation of the heart and blood vessels. |

| Direct-Acting Vasodilators | |

| Hydralazine (Apresoline) Minoxidil (Loniten) | These agents reduce blood pressure by promoting arteriole vasodilation. |

| Direct Renin Inhibitors | |

| Aliskiren (Tekturna) | This new class of drugs inhibits renin secretion from the kidney, reducing angiotensin I and angiotensin II, inhibiting vasoconstriction. |

The blood pressure of the elderly patient who is taking antihypertensive medication should be measured when the patient is sitting and when standing. Many of these medications can cause orthostatic hypotension; measuring blood pressure with the patient standing will reveal whether the medication is reducing the blood pressure too much. Assess patients receiving antihypertensives for dizziness, confusion, syncope, restlessness, and drowsiness, which may indicate hypotension.

Complications

Malignant hypertension is a term describing rapidly progressive moderate to severe hypertension that is difficult to control. Diastolic pressure ranges from 140 to 170 mm Hg, and unless effective intervention is found, the patient may suffer eye, heart, kidney, and brain damage.

Hypertensive Crisis

Hypertensive emergency is a life-threatening situation in which the blood pressure rises higher than 180/120 mm Hg and there is indication of target organ damage. Symptoms may include severe headache, blurred vision, seizures, nausea, and change in level of consciousness. It may occur if a patient has stopped taking antihypertensive medication, or it may be secondary to another disease process such as renal stenosis. The patient is placed in the intensive care unit and treated with intravenous (IV) emergency drugs, such as IV sodium nitroprusside (Nipride), nicardipine (Cardene IV), fenoldopam (Corlopam), or labetalol (Normodyne), to lower the blood pressure. A reduction in blood pressure to 160/100 mm Hg is desired over the first 2 hours. Blood pressure is monitored every 5 to 15 minutes. Medication is adjusted to reduce the pressure slowly to prevent renal, cerebral, or coronary ischemia. Hypertensive urgency occurs when the blood pressure rises to 180/120 mm Hg but there are no signs or symptoms of target organ damage. This is the more common occurrence. The patient is observed in the emergency department and treated with oral medication. The patient is directed to follow up with the primary care physician.

Nursing management

Assessment (Data Collection)

The patient should be assessed for indications of modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Physical assessment of the cardiac system should be performed. Assessment of blood pressure and documentation of levels and potential influences on values is an important aspect of nursing care. The patient’s blood pressure should be taken sitting, lying supine, and standing for a thorough assessment. Standing blood pressure measurements also are important when a patient is started on a new medication, particularly an ACE inhibitor, because orthostatic hypotension may occur.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

Common nursing diagnoses for a patient with hypertension include:

• Risk for injury related to complications of hypertension

• Deficient knowledge (disease process, medications) related to new diagnosis of hypertension

• Anxiety related to potential complications of disease process

Expected outcomes for a patient with hypertension may include:

• The patient will not experience retinopathy.

• The patient’s blood pressure will return to normal limits.

• The patient will verbalize an understanding of teaching related to medications and disease process.

• The patient will lose 10% of body weight in a designated period.

• The patient will be able to choose low-fat and low-sodium items from a variety of menus.

Implementation

Nursing interventions consist of assisting the patient to make necessary lifestyle changes that will help control the blood pressure and slow further atherosclerosis. Diet changes are often the most difficult for the patient. It is best to work with the patient’s current dietary likes and dislikes, modifying methods of food preparation to decrease sodium and fat content.

Sources of hidden sodium should be learned, and the patient should be taught how to read food labels.

Patients who need to increase potassium intake are taught to include citrus fruits and juices, beef and turkey, tomatoes, and potatoes in the diet. The person who does the shopping and food preparation must be included in the diet instruction process. Weight loss is the most important lifestyle change in obese clients. The goal is a weight that is within 15% of ideal body weight.

If caffeine restriction is recommended, teach the patient to gradually decrease his caffeine consumption so that he will not experience withdrawal symptoms, such as headache and nervousness. Remind the patient that many types of soft drinks, as well as coffee, tea, and chocolate, contain caffeine. Some of these beverages are available in decaffeinated formulas. Because it produces vasoconstriction, nicotine has a major impact on blood vessels and blood pressure. Stopping smoking can be a difficult task for many patients. Core Measures call for counseling and an information packet on smoking cessation to be given to the patient. An exercise program that fits the patient’s personality, ability, and preference should be designed. Walking to work from a parking lot a few blocks away, climbing stairs instead of using elevators, and a daily walk in the neighborhood often are sufficient. Other patients might prefer to use a stationary bicycle or treadmill. The object is to work on something that the patient will continue to do for the rest of his life.

Weight loss will begin to occur if the patient is faithful to the prescribed diet and exercise program. As his weight decreases, remind the patient of the direct effect these efforts have had on the blood pressure. Even a moderate weight loss of 7 to 12 lb (3 to 5 kg) can reduce blood pressure. Positive reinforcement should be given for even small amounts of weight loss.

Stress reduction requires an evaluation of lifestyle. Meditation, yoga, leisure activities, or just saying no to extra obligations can all decrease stress. Help the patient determine where his stressors are and what can practically be done to manage them. Lifetime compliance with diet, exercise, stress reduction, and medication plans is difficult for most patients. Alternative therapy may help.

Many do not understand or accept that it is up to them to control their disease. They do well for several months or a few years, but then, because they feel well (while their blood pressure has been controlled), they stop taking their medication and gradually return to previous lifestyle patterns. By teaching them what high blood pressure does to the blood vessels and the heart, brain, eyes, and kidneys, you can do much to encourage patients to follow the treatment plan for life. Each patient needs continuing praise for maintaining blood pressure control.

There are many resources to help hypertensive patients manage their illness more effectively. The American Heart Association, Heart Center Online, the National Institutes of Health, and many others offer educational materials for patients with hypertension. Healthy People 2020 goals and objectives have been written for hypertension.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree