Kathleen F. Jett

Cardiovascular and respiratory disorders

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

When I first had that heart attack, I was so frightened it seemed I would die just from the fear. It was the first time I realized how comforting, calm and efficient nurses could be. There was the one who came into the room a few days later and talked to me about the cardiac rehab program and that I could continue doing the things I had always done, except for changes in diet and more exercise. Even sex! I would never have asked that young thing, but she just told me it was OK.

Jerry, age 63

When Dad had that heart attack, it really scared us all, and I know we were afraid we would say or do something that would bring on another. I think he was also afraid of everything. I’m so grateful for the nurses at the hospital. They seem to give him lots of attention and information about the things he needed to know. He seems quite relaxed with himself now.

Ruth, Jerry’s youngest daughter

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Identify the most common types of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases occurring in late life.

• Discuss assessment of and intervention for cardiovascular and respiratory disease in the elder.

• Suggest ways to prevent cardiovascular and respiratory disease to the extent possible.

• Differentiate infectious, obstructive, and restrictive lung disease.

• Discuss the signs and symptoms of pneumonia in which rapid hospitalization may be recommended.

• Develop a tuberculosis surveillance plan for a long-term care facility.

Glossary

Comorbidity More than one disease or health condition existing at the same time.

Dyspnea The subjective sensation of shortness of breath.

Morbidity Disability as the result of a health condition.

Mortality Death as a result of a health condition or event.

Nosocomial Pertaining to the institutional setting or treatment as the source (as in nosocomial infection).

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Caring for older adults means caring for persons with cardiovascular disease (CVD), respiratory problems, or both. These two systems are interconnected. A problem in one is likely to cause or complicate a problem in the other. When the nurse is addressing a cardiac problem, such as heart failure, the respiratory system must be assessed as well. For example, pneumonia may trigger heart failure. Nursing interventions frequently overlap. One carefully planned action can address several systems at the same time and achieve goals meeting basic physiological needs and promoting healthy aging as much as possible.

Cardiovascular disease

The American Heart Association identifies the major cardiovascular diseases as hypertension (HTN); coronary heart disease (CHD), including myocardial infarction (MI) and angina; and heart failure (HF). Although the numbers of deaths from heart disease have decreased, they remain the first and third cause of death and common causes of disability. It is the number one cause of death for African Americans, Caucasians, and Hispanics and second behind cancer for American Indians and Pacific Islanders (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012c). The rate of deaths per 100,000 increases dramatically with age from a combination of normal changes with aging and the presence of risk factors (Box 19-1). Older adults also undergo the majority of CVD-related procedures, but treatment approaches are highly variable by ethnicity and sex (Box 19-2).

Hypertension

Hypertension (HTN) is the most common chronic cardiovascular disease encountered by the gerontological nurse. It affects 70.34% of those over 65 years of age (Health Indicators Warehouse, 2005-2008a) but is only controlled in 45.64% of those persons (Health Indicators Warehouse, 2005-2008b). Both the definition of and the guidelines for treatment of HTN are provided by the Joint National Committee on the Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC) (Box 19-3). HTN is diagnosed any time the diastolic blood pressure reading is 90 mm Hg or higher or the systolic reading is 140 mm Hg or higher on two separate occasions (JNC, 2003) (Table 19-1). More recently a joint consensus report of leading authorities in aging and cardiology recommended that three separate readings be used in older adults due to the variability inherent with the less compliant vasculature that is associated with aging (American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association [ACCF/AHA], 2011).

TABLE 19-1

| Classification | Blood Pressure |

| Normal | <120 systolic and <80 diastolic |

| Prehypertension | 120-139 systolic or 80-89 diastolic |

| Stage 1 HTN | 140-159 systolic or 90-99 diastolic |

| Stage 2 HTN | >160 systolic or >100 diastolic |

Blood pressure increases slightly with age, with a leveling off or decrease of the diastolic pressure for persons about 60 years of age and older. Older adults most often have isolated systolic hypertension, which is an elevation in only the systolic reading. This is quite different from the younger person, who is more likely to have an elevation in just the diastolic or in both. During the JNC’s last review (#7) in 2003, it was noted that the definition for HTN does not change with age. The current blood pressure goal for all persons is 120/60 mm Hg (JNC, 2003). It is anticipated that the updated JNC 8 guidelines will be prepared soon.

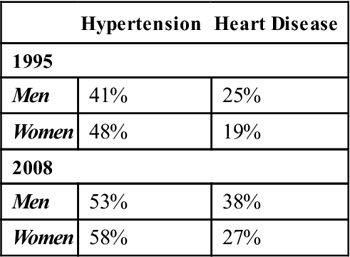

Although often treatable, and in some cases preventable, the rate of HTN has increased in the last 15 or so years, especially for women (Table 19-2) and significant disparities between racial and ethnic groups persist. Although race, ethnicity, and a family history of hypertension cannot be changed, a number of other factors are within control of the individual to reduce his or her risk for hypertension (Box 19-4).

TABLE 19-2

Comparative Rates of Hypertension and Heart Disease

| Hypertension | Heart Disease | |

| 1995 | ||

| Men | 41% | 25% |

| Women | 48% | 19% |

| 2008 | ||

| Men | 53% | 38% |

| Women | 58% | 27% |

Adapted from Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics: Older Americans 2000: key indicators of well-being and Older Americans 2010: key indicators of well-being. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, Washington, DC, 2000 and 2010, U.S. Government Printing Office. Available at http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet.

Most HTN is discovered during health screening or examination for another problem, when related complications may have already developed (see the Evidence-Based Practice box). The most important complication of HTN is the long-term effects resulting in what is referred to as “end-organ damage,” especially to the heart. Older persons with HTN have an absolute higher risk for cardiac disease such as CHD, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure, as well as acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and sudden death. Poorly controlled HTN is also implicated in chronic renal insufficiency, end-stage renal disease, and peripheral vascular disease (ACCF/AHA, 2011).

Heart disease

The beating heart, like other muscles, needs oxygen and other nutrients to provide energy for its work. However, the blood passing through the heart with each beat is not available to provide oxygen or nutrients to the organ itself. Instead, like all other muscles, the heart receives its oxygen from arteries within it.

Heart disease (HD) is also referred to as coronary heart disease (CHD) and coronary artery disease (CAD). It develops from a number of causes, including stiffening of the blood vessels, referred to as arteriosclerosis or “hardening of the arteries,” and when cholesterol and other fats are deposited in the layers of the arteries. Both of these reduce the blood flow through the heart vessels limiting the amount of oxygen reaching the tissue. HD is also a direct consequence of chronic, untreated or inadequately treated hypertension (Buttaro et al., 2008). The extent to which one suffers from HD is greatly affected by a personal history of exposure to smoke and pollutants and whether one also has diabetes or family history of such.

Heart disease can result in ischemia or when there is a sudden complete blockage of oxygen to the heart muscle. When the blockage is sudden but shortly resolves on its own it is called angina. A more serious and often permanent blockage is referred to as a myocardial infarction or acute MI (AMI). An AMI is seen as gripping chest pain, radiation to the shoulder, etc., in younger adults, but not always in the older adult. Instead the older adult is more likely to have what is called a silent MI. His or her discomfort may be mild and may be localized to the back, the abdomen, the shoulders, or either or both arms. Nausea and vomiting, or merely a sensation like heartburn, may be the only symptoms. More often there are no noticeable signs or symptoms at all, and the event is only noticed at the time of death or when an electrocardiogram (ECG) is performed for some other purpose. These vague symptoms often are not brought to the attention of a medical provider. Only about 45% of persons over 65 years of age are aware of even the usual symptoms and the appropriate response, making the risk for death associated with an AMI high (Health Indicators Warehouse, 2008).

Heart failure

The damage to the heart from chronic HD or MI may lead to heart failure (HF), which is the most frequent discharge diagnoses for non-traumatic hospitalization of an older adult. Often this results in a transfer to a long-term care facility (Fang et al., 2008).

HF is a disease of the heart muscle in which the muscle is damaged, malfunctions, and can no longer pump enough blood to meet the needs of the body. In 2008 it affected over 5.7 million people in the United States, the majority of whom are over 65 years of age (CDC, 2012d). Causes of HF include hypertension, fever, hypoxia, anemia, metabolic disease, and infection (ACCF/AHA, 2011). Over time the heart is further damaged because of poor control of the underlying problem (e.g., hypertension) leading to more and more severe HF, known as congestive heart failure (CHF). An unhealthy diet, smoking, and lack of exercise aggravate the development of heart disease and the extent of damage, especially for those who have a family (genetic) history of heart disease. There is no cure for HF, only the management of symptoms and the attempt to prevent worsening. Fifty percent of persons with heart failure die within 5 years of diagnosis (CDC, 2012c).

Common signs and symptoms of heart failure in the elderly include fatigue or shortness of breath (dyspnea) with exertion, inability to lie flat without getting short of breath (orthopnea), waking up at night gasping for air, weight gain, and swelling in the lower extremities. Dyspnea may occur at rest or on exertion (DOE), or it may appear intermittently at night (paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea). The dyspnea may be relieved by sitting up or sleeping on multiple pillows or with the head of the bed elevated. If a cough is present, it is worse at night. The New York Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology–American Heart Association provide us with convenient ways to classify the symptomatic experience of the HF, from symptom-free to severely disabled (Box 19-5).

In addition, the nurse should be alert for the atypical clinical presentation of exacerbations of HF in the elderly. The person may appear confused, or delirious; begin falling; or complain of insomnia or urinary frequency at night (nocturia). He or she may complain of dizziness or may have syncope (fainting). Or more often, the nurse will notice that the person has the “droops,” or malaise and a subtle decline in activity tolerance or functional or cognitive abilities. The need for hospitalization is frequent. However, due to the added risks for the older adult in the acute care setting, a goal of Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2012) is to reduce these and attempt to identify the need for more aggressive treatment earlier, thus potentially avoiding an inpatient stay (see the Healthy People box).

Implications for gerontological nursing and healthy aging

Assessment

As with any assessment, obtaining a pertinent history of the events leading up to and including the presentation of cardiovascular problems is essential, whether the history is from the patient or a friend or family member. Monitoring of vital signs, laboratory results, and kidney function, and assessing the cardiac and respiratory function and conducting a mental status exam are essential. An auscultatory gap, or time when the second heart sound ceases, begins again, and then finally is not heard, is common in the older adult (ACCF/AHA, 2011). The results of home monitoring may be particularly useful. Members of the University of Iowa Gerontological Nursing Intervention Center offer an evidence-based assessment tool that can be used as a basic assessment measure as well as one that indicates change in long-term care patients with heart failure (Harrington, 2008). The tool can be used to document status in three categories: activities of daily living, quality of sleep, and dyspnea. It is available for purchase at www.nursing.uiowa.edu/excellence/nursing_interventions/index.htm.

Interventions

For the person with CVD, the goals of therapy are to provide relief of symptoms, improve the quality of life, reduce mortality and morbidity, and slow or stop progression of dysfunction through the use of aggressive drug therapy. A key intervention to reduce heart attack–related disability and death is to teach all persons the warning signs and what to do if these are experienced. Additional goals are to maximize the elder’s function and quality of life and, when appropriate, provide expert palliative care. Concurrent and supportive therapies include modifying the diet by decreasing fat, cholesterol, and sodium; exercise; education; and family and social supports (ACCF/AHA, 2011).

Nursing interventions assist the person to accomplish these goals and have been found to be highly effective (Sisk et al., 2006). What specific interventions are used will depend on the severity of the disease, the person, and the desire for either palliative or aggressive care. Nursing actions range from teaching the older adult about lifestyle changes in diet, activity, and rest (see Chapter 11), to acute measures, such as the administration of oxygen. Interventions about which the nurse should be knowledgeable are related to those assessed (Box 19-6).