Men’s Health

Carrie Morgan

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Identify the major indicators of men’s health status.

2. Describe physiological and psychological factors that have an impact on men’s health status.

3. Discuss barriers to improving men’s health.

4. Discuss factors that promote men’s health.

5. Describe men’s health needs.

Key terms

acute condition

androgen

chronic condition

illness orientation

life expectancy

medical care

morbidity

mortality

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

It is common knowledge that women live longer than men and that health care use is greater among women than men. Death rates for men are higher than for women in the major causes of death. Although the overall interest in health promotion and illness prevention has increased, men’s health issues remain largely unaddressed (Baerlocher and Verma, 2008). Women’s health has become a specialty practice with courses and programs available in many colleges of nursing. A specialty in men’s health has not been established.

This chapter focuses on exploring the health needs of men and the implications for community health nursing. Specific areas that are discussed include the current health status of men, physiological and psychological theories that attempt to explain men’s health, factors that impede men’s health, factors that promote men’s health, men’s health needs, and planning gender-appropriate care for men at the individual, family, and community levels.

Men’s health status

Traditional indicators of health for all persons include rates of longevity, mortality, and morbidity. Reviewing these rates provides nursing students with a better understanding of the community aggregate.

Longevity and Mortality in Men

Major gender differences in longevity and mortality rates reveal that men remain disadvantaged despite advances in technology. Although women are more likely to use health services and have higher morbidity rates, mortality rates for men remain higher. Gender differences are generally associated with both physiological and behavioral factors, which place men at greater risk of death. These behavioral factors, together with men’s reluctance to seek preventive and health services, have marked implications for community health nursing.

Longevity

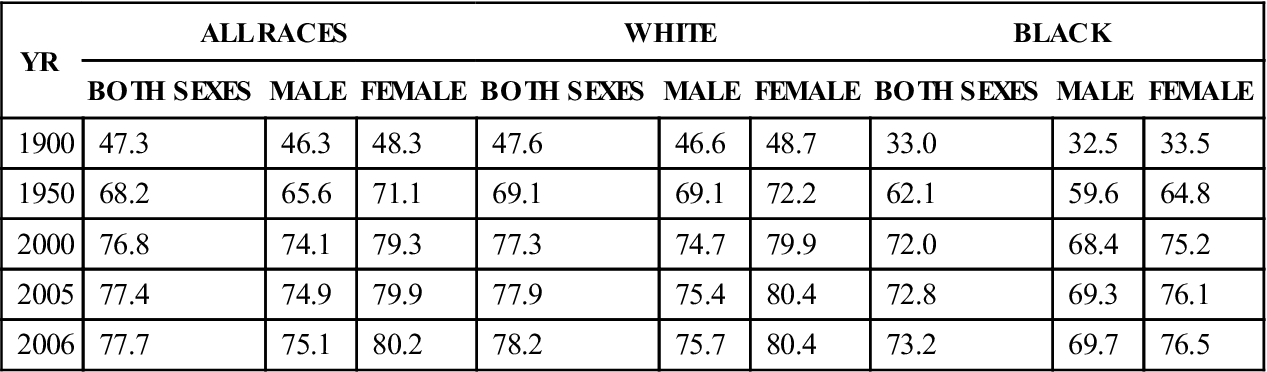

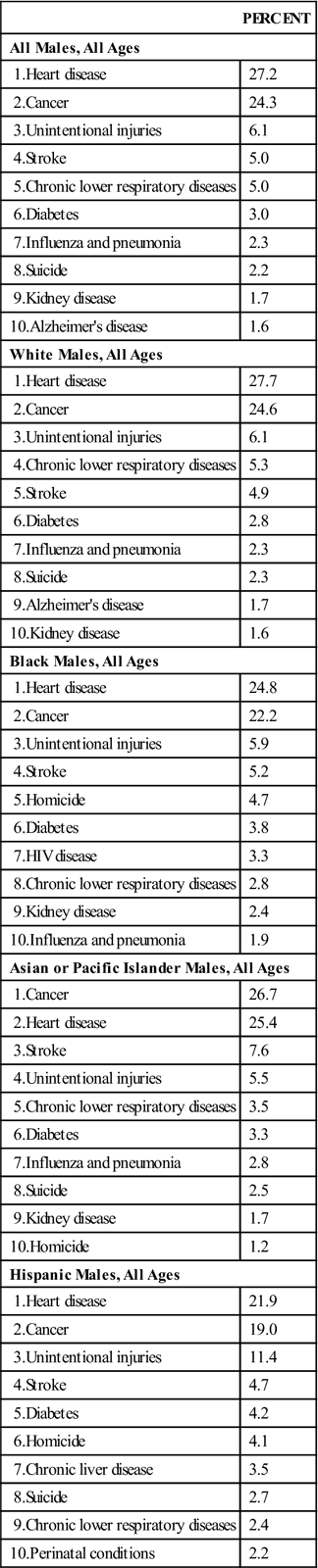

Rates of longevity are increasing for both men and women. People can now expect to live more than 20 years longer than their forefathers and foremothers lived at the turn of the nineteenth century. Infants born in the United States in 1996 can expect to live 77 years, whereas those born in 1900 lived an average of 47.3 years when the death rate was highest. Life expectancy for both males and females has increased; however, since the 1970s this gender gap in longevity has decreased (Table 18-1). Between 2005 and 2006, men gained 0.2 year of longevity while females gained 0.3 year of longevity (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2009). This change in male longevity may be attributed to the advances in treatment of heart disease and cancer, which have been the major causes of death in U.S. males (Table 18-2).

TABLE 18-1

Life Expectancy At Birth According To Sex And Race, United States: 1900, 1950, 2000, 2005, 2006

| YR | ALL RACES | WHITE | BLACK | ||||||

| BOTH SEXES | MALE | FEMALE | BOTH SEXES | MALE | FEMALE | BOTH SEXES | MALE | FEMALE | |

| 1900 | 47.3 | 46.3 | 48.3 | 47.6 | 46.6 | 48.7 | 33.0 | 32.5 | 33.5 |

| 1950 | 68.2 | 65.6 | 71.1 | 69.1 | 69.1 | 72.2 | 62.1 | 59.6 | 64.8 |

| 2000 | 76.8 | 74.1 | 79.3 | 77.3 | 74.7 | 79.9 | 72.0 | 68.4 | 75.2 |

| 2005 | 77.4 | 74.9 | 79.9 | 77.9 | 75.4 | 80.4 | 72.8 | 69.3 | 76.1 |

| 2006 | 77.7 | 75.1 | 80.2 | 78.2 | 75.7 | 80.4 | 73.2 | 69.7 | 76.5 |

Data from National Center for Health Statistics: Health, United States: 2004, Hyattsville, MD, 2006, US Public Health Service.

TABLE 18-2

Leading Causes of Death in Males, United States, 2004

| PERCENT | |

| All Males, All Ages | |

| 1.Heart disease | 27.2 |

| 2.Cancer | 24.3 |

| 3.Unintentional injuries | 6.1 |

| 4.Stroke | 5.0 |

| 5.Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 5.0 |

| 6.Diabetes | 3.0 |

| 7.Influenza and pneumonia | 2.3 |

| 8.Suicide | 2.2 |

| 9.Kidney disease | 1.7 |

| 10.Alzheimer’s disease | 1.6 |

| White Males, All Ages | |

| 1.Heart disease | 27.7 |

| 2.Cancer | 24.6 |

| 3.Unintentional injuries | 6.1 |

| 4.Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 5.3 |

| 5.Stroke | 4.9 |

| 6.Diabetes | 2.8 |

| 7.Influenza and pneumonia | 2.3 |

| 8.Suicide | 2.3 |

| 9.Alzheimer’s disease | 1.7 |

| 10.Kidney disease | 1.6 |

| Black Males, All Ages | |

| 1.Heart disease | 24.8 |

| 2.Cancer | 22.2 |

| 3.Unintentional injuries | 5.9 |

| 4.Stroke | 5.2 |

| 5.Homicide | 4.7 |

| 6.Diabetes | 3.8 |

| 7.HIV disease | 3.3 |

| 8.Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 2.8 |

| 9.Kidney disease | 2.4 |

| 10.Influenza and pneumonia | 1.9 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander Males, All Ages | |

| 1.Cancer | 26.7 |

| 2.Heart disease | 25.4 |

| 3.Stroke | 7.6 |

| 4.Unintentional injuries | 5.5 |

| 5.Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 3.5 |

| 6.Diabetes | 3.3 |

| 7.Influenza and pneumonia | 2.8 |

| 8.Suicide | 2.5 |

| 9.Kidney disease | 1.7 |

| 10.Homicide | 1.2 |

| Hispanic Males, All Ages | |

| 1.Heart disease | 21.9 |

| 2.Cancer | 19.0 |

| 3.Unintentional injuries | 11.4 |

| 4.Stroke | 4.7 |

| 5.Diabetes | 4.2 |

| 6.Homicide | 4.1 |

| 7.Chronic liver disease | 3.5 |

| 8.Suicide | 2.7 |

| 9.Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 2.4 |

| 10.Perinatal conditions | 2.2 |

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Women’s Health, Department of Health and Human Services, 2008: www.cdc.gov/men/lcod/index.htm.

Factors that influence the incongruencies between males and females are race or ethnic origin, social economic status, and education. Reported by race, gender mortality rates show that less-advantaged populations in the United States, especially minorities, live significantly fewer years. African-American males live 6 years less than white males (NCHS, 2009). Native American males live an average of 4 years less than white males. Hispanics have a life expectancy comparable with that of their white counterparts.

Mortality

The United States lags behind several other countries in mortality rates for males. In 2005 only four countries had mortality rates higher than the United States: Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, and Slovakia (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2007). In the United States, as in most industrialized countries, males lead females in mortality rates in each leading cause of death. Although males were the primary source of medical data before the 1970s, and most of the treatment advances have been developed from these data, gender-related disparity in death rates continues. Other factors also account for this mortality gender gap.

The gender disparity for disease-related deaths has narrowed. Heart disease remains the leading cause of death, but the ratio of death for heart disease decreased by 2.8 between 2005 and 2006. During this same period of time, male-to-female deaths increased by 1.4. Since the 1990s, female, cancer-related deaths have declined at a slower rate than men’s. Lifetime risk for lung cancer among males is estimated to be 9.8%, and 3.8% for females (Lynch, 2008). The death rate for chronic lower respiratory tract disease among females increased 150% between 1980 and 2002, whereas death rates for males increased 7% (NCHS, 2004b). This may be associated with the increase in incidence of lower respiratory disease among the elderly (Lynch, 2008). Unintentional injury deaths due to accidents, suicide, or homicide for the whole population have increased by 1.8 from 2005-2006. Males continue to be at risk for death due to unintentional injury. Males aged 15 to 64 years are two to three times more likely to die as a result of unintentional injury than females of the same age. Men are five times more likely to commit suicide. Males over age 85 years are eleven times more likely to die as a result of suicide.

Race and ethnic background also are factors to be considered when evaluating male mortality rates. Black men between ages 45 and 64 years are more than ten times as likely to die of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection as white males. Among males aged 15 to 24 years, African-American males are twice as likely to die of vehicle accidents and seven times more likely to die of homicide (NCHS, 2004b). Hispanic males fare somewhat better but are twice as likely to die as a result of homicide as white males.

Morbidity

Despite the differences in mortality rates, men tend to perceive themselves to be in better health than women do (Brown and Bond, 2008). In the National Health Interview Survey of 2003 (NCHS, 2004b), which asked people to rate their health status, men were more likely to rate their health as excellent or very good as opposed to fair or poor. Morbidity rates, or rates of illness, are difficult to obtain and have been available usually only in Western industrialized countries. For example, in the United States, reports of analyses of morbidity rates by gender lag several years behind analyses of mortality rates by gender. Gender differences in morbidity rates reflect the latest available reports. The following are common indicators of morbidity rate:

Although variations exist, women are more likely to be ill, whereas men are at greater risk for death.

Acute Illness

According to the National Health Interview Survey, an acute condition is a type of illness or injury that usually lasted less than 3 months and either resulted in restricted activity (e.g., causing a person to limit daily activities for at least half a day) or caused the patient to receive medical care. The incidence rate for acute infective and parasitic disease, digestive system conditions, and respiratory conditions is higher for women than for men (Benson and Marano, 2001-2002). The only exception is for injuries, which were 1.5 times greater for men in 2006 (National Vital Statistics Reports, 2009). In addition, the severity of these injuries is reported to be greater in men than in women. When conditions associated with childbearing are excluded from the list of acute illnesses, the incidence rate for women remains 18% greater than for men.

Women reported that they slowed their activities and rested more often than men. The number of restricted-activity days associated with acute conditions per 100 people is 33% greater for women than for men; similarly, the number of bed days associated with acute conditions per 100 people is 38% greater for women than for men (Benson and Marano, 2001).

Chronic Conditions

A chronic condition is a condition that persists for at least 3 months or belongs to a group of conditions classified as chronic regardless of time of onset, such as tuberculosis, neoplasm, or arthritis. In general, women have higher morbidity rates than men. Women are more likely than men to have a higher prevalence of chronic diseases that cause disability and limitation of activities but do not lead to death. However, men have higher morbidity and mortality rates for conditions that are the leading causes of death.

Use of medical care

Medical care, the use of ambulatory care, hospital care, preventive care, or other health services, also illustrates the different gender patterns.

Use of Ambulatory Care

Men seek ambulatory care less often than women. According to the 2003 National Health Interview Survey (NCHS, 2004b), the physician’s office is the primary setting for ambulatory care for both men and women. In this report, males visited physician offices, outpatient departments, or emergency departments less often than women in all age groups, with the exception of males over age 75 years. Men were likely to visit a physician only if a specific health-related symptom was experienced (Brown and Bond, 2008). Injury-related visits to hospital emergency departments are higher for males than females. Males aged 18 to 24 years are twice as likely to visit hospital emergency departments for unintentional injuries as females in the same age range. Even though gender differences in ambulatory care utilization are lessening, males continue to delay medical treatment, resulting in men being sicker when they do seek health care. Because they are sicker, they require more intensive medical care. Physicians see men more frequently than women for the chronic diseases that are more prevalent among them. Males are twice as likely to visit specialists (Singh-Manoux, et al., 2008).

Use of Hospital Care

The literature indicates that hospitalization rates also vary by sex. In 2003, rates of discharges from short-stay hospitals were lower for males (102 per 1000) than for females (133 per 1000), even when discharges for deliveries were excluded. However, males had a longer length of stay in the hospital than females (4.3 vs. 3.8 days). Discharge rates increase for both men and women after 45 years of age; however, rates for men increase more rapidly. After 65 years of age, men’s discharge rates continue to be higher than women’s rates (NCHS, 2004b).

Use of Preventive Care

Preventive examinations and appropriate health protective behavior are necessary for health promotion and early diagnosis of health problems. Men do not engage in these health protective behaviors at the same frequency as females (Brown and Bond, 2008). Most men do not have routine checkups. National health surveys indicate that women are more likely than men to receive physical examinations (NCHS, 2004b). Men are twice as likely to report no usual source of care although eligibility for primary care in males exceeds that for females (Lynch, 2008).

Use of Other Health Services

Admission for serious mental disease accounts for the largest number of hospital admissions for men aged 45 to 74 years. Women of the same age are more likely to be admitted for disease of the heart. Women are also more likely to reside in nursing homes because they have a longer life expectancy. Men are more likely than women to be admitted for psychiatric services in state and county mental hospitals (NCHS, 2004b).

Theories that explain men’s health

As discussed previously, a gender gap exists in health. The data reviewed raise many questions for community health nurses to explore, regarding gender differences in health and illness. Although men have shorter life expectancy and higher rates of mortality for all leading causes of death, women have higher rates of morbidity, including rates of acute illness and chronic disease and use of medical and preventive care services. Verbrugge and Wingard (1987) asked why “females are sicker, but males die sooner” (p. 135). Several explanations exist for this paradox.

Nurses traditionally use developmental theories to explain individual behavior. Erickson’s model was not gender specific (Levinson focused somewhat on male development). There remains a need for literature detailing the factors and combinations of factors that influence gender differences in the health and illness of populations.

The following explanations proposed by Waldron (1995a, 1995b, 1995c, 1995d, 1995e) and Verbrugge and Wingard (1987) attempt to account for gender differences in this important area:

Biological Factors

Several biological factors influence sex differences in mortality and morbidity rates, including genetics, effects of sex hormones, and physiological differences, which may be influenced by genetics, hormones, and environmental factors (Waldron, 1995a, 1995b, 1995c, 1995d, 1995e). The embryo is unisexual until the seventh week of gestation. Androgen, a hormone from the Y-chromosome coupled with the maternal androgen source, results in the development of the male sex. More male births occur than female births. In 2003, 1049 male births occurred for every 1000 female births. However, infant mortality rate for males was 9% higher than for females, thus reducing this ratio. Sex ratios at birth appear to be lower for births to older fathers, black fathers, higher-order births (i.e., second, third, or fourth births), and births after induced ovulation.

Whether sex ratios at birth are influenced by sex ratios at conception or sex differentials in mortality rates before birth is unknown. Current evidence suggests that more than two out of three prenatal deaths occur before clinical recognition of the pregnancy. Embryonic research shows excess male fetuses in early pregnancy and less male delivery at term. Males’ experience of higher mortality rates for perinatal conditions is attributed to biological disadvantages such as males’ greater risk of premature birth, higher rates of respiratory distress syndrome, and infectious disease in infancy resulting from the influence of male hormones on the developing lungs, brain, and possibly the immune system of the male fetus (National Vital Statistics Reports, 2009). Sex chromosome–linked diseases, such as hemophilia and certain types of muscular dystrophy, are more common among males than females (Waldron, 1995d).

Biological advantages for females may also exist later in life because the mechanism produced by estrogen protects against heart disease. Some evidence supports the hypothesis that men’s higher testosterone levels contribute to men’s lower high-density lipoprotein levels. Body fat distribution, specifically the tendency for men in Western countries to accumulate abdominal body fat versus the tendency for women to accumulate fat on the buttocks and thighs, may also contribute to sex differences in development of metabolic syndrome (Kirby et al., 2006). Men’s higher levels of stored iron also may contribute to risk for ischemic heart disease. Some additional physiological gender differences are the following (Tanne, 1997):

Socialization

A second theory for explaining sex differences in health is socialization, especially within the area of masculinity. Society emphasizes assertiveness, restricted emotional display, concern for power, and reckless behavior in males. Pursuit of these attributes results in increased risks in work, leisure, and lifestyle. Internalization of these norms of masculinity reduces the likelihood of engaging in health promotion behaviors for fear these behaviors might be interpreted as a sign of weakness. Gender-role socialization may influence these differences. Peer pressure plays an important role in adhering to masculine norms. Men enculturate their sons to believe that risking personal injury demonstrates masculinity (Brown and Bond, 2008).

According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Workers Health Chartbook (2004), 54.2% of U.S. workers are males. Male workers account for 66.1% of the reported occupational injuries and 92% of work-related fatalities. Men’s higher exposure to carcinogens at the work site is associated with high rates of mesothelioma and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis. In the United States, men score higher than women on measures of hostility and lack of trust of others, which may place them at higher risk of ischemic heart disease. Although occupational hazards to women’s health are being identified, evidence indicates that, unlike for men, employment of U.S. women outside the home has a positive effect.

Popular male leisure, sports, and play activities place men at high risk for injury. Males between the ages of 18 and 24 years are twice as likely as women to visit a hospital emergency department because of motor vehicular accidents, stabs, or intentional injury (NCHS, 2004b). Statistics show that men drive faster than women, receive more traffic violations, and are less likely to wear seat belts, all of which contribute to a greater number of motor vehicle fatalities. Although prevalence of smoking is decreasing, 25.5% of males smoke (NCHS, 2004b); 68% of men consume alcohol, and men are five times more likely than women to drink heavily. Males have a greater use of illegal psychoactive substances and are three times more likely to be involved in criminal activity (NCHS, 2004b).

Men are more likely to be involved in violent crimes, and violence is a typical precursor to homicide. Men are victims in four out of five homicides. Black males are involved in a homicide seven times more often than European-American males (NCHS, 2004a).

Many barriers exist that prohibit positive male health behavior changes, but female family members were seen as facilitators. Cheatham and colleagues (2008) reported that several studies showed males to be more likely to change health behaviors when these changes were suggested and supported by female family members who they thought were concerned about the well-being of the man.

Orientation Toward Illness and Prevention

Illness orientation, or the ability to note symptoms and take appropriate action, also may differ between the sexes. Most diseases, injuries, and deaths prevalent among men are preventable. However, the stereotypical view of men as strong and invulnerable is incongruent health promotion. Boys are socialized to ignore symptoms and “toughen up.” Surveys done by Men’s Health reveal that 9 million men have not seen a health care provider in 5 years. Men may be aware of being ill, but they make a conscious decision not to seek health care to avoid being labeled as “sick.” Brown and Bond (2008) suggest that men lack the somatic awareness and are less likely to interpret symptoms as indicators of illness. There may be a desire to rationalize symptoms and denial of susceptibility to disease that contributes to the delay in treatment (Brown and Bond, 2008).

Health protective behavior, or the ability to take action to prevent disease or injury, also may vary between the sexes. Perhaps as a result of the contraceptive developments of the 1970s, women have a higher likelihood to seek preventive examinations. Routine reproductive health screening (i.e., the Pap test and breast examination) has been expanded to include some general screening, such as testing blood pressure, urine, and blood for chronic problems. Men do not have routine reproductive health checkups that include screening, which would detect other health problems at an early stage. Among respondents to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, more women than men reported wearing seat belts, receiving blood pressure checks, having their blood cholesterol checked, and seeking help for an emotional or personal problem in the past year (NHIS, 2002a). Men reported spending more time in leisure activities than women, including playing sports regularly. The rapid growth of gymnasiums and health spas indicates a growing interest in maintaining physical fitness. Only 4.9% of male respondents and 5.5% of female respondents reported knowing that exercise periods of 20 minutes per session three times per week are necessary to strengthen the heart and lungs.

The survey results also revealed that in other areas of preventive health behaviors, men are less likely than women to visit a dentist, and 26.1% of men over age 65 years have no natural teeth. Males tend to participate in exercise, but 68% of men over 20 years of age are overweight. Men consume more fatty foods and are less likely than women to change their eating habits.

Gender differences in preventive health behavior are a fertile ground for continued research. Meryn (2009) reported that 21% of research was devoted to men’s health compared with 53% for female health. He suggests that large-scale research in this area would add to the small evidence bases of health promotion behaviors among men. Specific national health objectives have only recently addressed the health care needs of this aggregate. Uniformly recognized preventive screening programs for males have only recently been developed. With the advent of managed care, men who are eligible for coverage will have access to these routine health screenings. However, it is undetermined whether men will take advantage of these programs. Box 18-1 discusses matters related to men’s reproductive health needs.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree