1 Identify the signs and symptoms of psychotic behavior. 2 Describe the major indications for the use of antipsychotic agents. 3 Discuss the antipsychotic medications that are used for the treatment of psychoses. 4 Identify the common adverse effects that are observed with the use of antipsychotic medications. psychosis ( delusion ( hallucinations ( disorganized thinking ( loosening of associations ( disorganized behavior ( changes in affect ( target symptoms ( typical (first-generation) antipsychotic agents ( atypical (second-generation) antipsychotic agents ( equipotent doses ( extrapyramidal symptoms (EPSs) ( dystonias ( pseudoparkinsonian symptoms ( akathisia ( tardive dyskinesia ( abnormal involuntary movement scale (AIMS) ( Dyskinesia Identification System Condensed User Scale (DISCUS) ( neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) ( depot antipsychotic medicine ( Psychosis does not have a single definition but is a clinical descriptor applied to someone who is out of touch with reality. Psychotic symptoms can be associated with many illnesses, including dementias and delirium that may have metabolic, infectious, or endocrinologic causes. Psychotic symptoms are also common in patients with mood disorders such as major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Psychosis can also be caused by many drugs (e.g., phencyclidine, opiates, amphetamines, cocaine, hallucinogens, anticholinergic agents, alcohol). Psychotic disorders are characterized by loss of reality, perceptual deficits such as hallucinations and delusions, and deterioration of social functioning. Schizophrenia is the most common of the several psychotic disorders defined by the American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revised (DSM-IVR). Psychotic disorders are extremely complex illnesses that are influenced by biologic, psychosocial, and environmental circumstances. Some of the disorders require several months of observation and testing before a final diagnosis can be determined. It is beyond the scope of this text to discuss psychotic disorders in detail, but general types of symptoms associated with psychotic disorders will be described. A delusion is a false or irrational belief that is firmly held despite obvious evidence to the contrary. Delusions may be persecutory, grandiose, religious, sexual, or hypochondriacal. Delusions of reference—in which the patient attributes a special, irrational, and usually negative significance to other people, objects, or events, such as song lyrics or newspaper articles, in relation to self—are common. Delusions may be defined as “bizarre” if they are clearly irrational and do not derive from ordinary life experiences. A common bizarre delusion is the patient’s belief that his or her thinking process, body parts, or actions or impulses are controlled or dictated by some external force. Hallucinations are false sensory perceptions that are experienced without an external stimulus and seem real to the patient. Auditory hallucinations experienced as voices that are characteristically heard commenting negatively about the patient in the third person, are prominent among patients with schizophrenia. Hallucinations of touch, sight, taste, smell, and bodily sensation also occur. Disorganized thinking is commonly associated with psychoses. These thought disorders may consist of a loosening of associations or a flight of ideas so that the speaker jumps from one idea or topic to another unrelated one (derailment) in an illogical, inappropriate, or disorganized way. Answers to questions may be obliquely related or completely unrelated (tangentiality). At its most serious, this incoherence of thought extends into pronunciation itself, and the speaker’s words become garbled or unrecognizable. Speech may also be overly concrete (loss of ability to think in abstract terms) and inexpressive; it may be repetitive and may convey little or no real information. Disorganized behavior is another common characteristic of psychosis. Problems may be noted with any form of goal-directed behavior, leading to difficulties with performing activities of daily living (ADLs), such as organizing meals or maintaining hygiene. The patient may appear markedly disheveled, may dress in an unusual manner (e.g., wearing several layers of clothing, scarves, and gloves on a hot day), or may display clearly inappropriate sexual behavior (e.g., public masturbation) or unpredictable, nontriggered agitation (e.g., shouting, swearing). Disorganized behavior must be distinguished from behavior that is merely aimless or generally not purposeful and from organized behavior that is motivated by delusional beliefs. Changes in affect may also be symptoms of psychosis. Emotional expressiveness is diminished; there is poor eye contact and reduced spontaneous movement. The patient appears to be withdrawn from others, and the face appears to be immobile and unresponsive. Speech is often minimal, with only brief, slow, monotone replies given in response to questions. There is a withdrawal from areas of functioning that affect interpersonal relationships, work, education, and self-care. The importance of the initial assessment for an accurate diagnosis cannot be underestimated for a patient with acute psychosis. A thorough physical and neurologic examination, a mental status examination, a complete family and social history, and a laboratory workup must be performed to exclude other causes of psychoses, including substance abuse. Both drug and nondrug therapies are critical to the treatment of most psychoses. Long-term outcome is improved for patients with an integrated drug and nondrug treatment regimen. Nonpharmacologic interventions beneficial to patients include (1) individual psychotherapy to improve insight into the illness and help the patient cope with stress, (2) group therapy to enhance socialization skills, (3) behavioral or cognitive therapy, (4) and vocational training. Referral to community resources such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) may provide additional support for the patient and family. Before initiating therapy, the treatment goals and baseline level of functioning must be established and documented. Target symptoms must also be identified and documented. Target symptoms are critical monitoring parameters used to assess changes in an individual’s clinical status and response to medications. Examples of target symptoms include frequency and type of agitation, degree of suspiciousness, delusions, hallucinations, loose associations, grooming habits and hygiene, sleep patterns, speech patterns, social skills, and judgment. The ultimate goal is to restore behavioral, cognitive, and psychosocial processes and skills to as close to baseline levels as possible so that the patient can be reintegrated into the community. Realistically, unless the psychosis is part of another medical diagnosis such as substance abuse, most patients will have recurring symptoms of the mental disorder for most of their lives. Therefore, treatment is focused at decreasing the severity of the target symptoms that most interfere with functioning. A variety of scales have been developed to assist with the objective measurement of change in target symptoms in response to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. These include the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia (PANSS), the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale, and the Rating of Aggression Against People and/or Property (RAAPP) scale. Pharmacologic treatment of psychosis includes several classes of drugs. The most specific are the first- and second-generation antipsychotic agents, but benzodiazepines (see p. 217) are often used to control acute psychotic symptoms. Beta-adrenergic–blocking agents (beta blockers) (e.g., propranolol) (see p. 206), lithium (see p. 271), anticonvulsants (valproic acid, see p. 306; carbamazepine, see p. 296), antiparkinsonian agents (see Chapter 15), and anticholinergic agents (see p. 209) occasionally play a role in controlling the adverse effects of medications used in antipsychotic therapy. Antipsychotic (also known as neuroleptic) medications can be classified in several ways. Traditionally, they have been divided into phenothiazines and nonphenothiazines. Antipsychotic medications can also be classified as low-potency or high-potency drugs. The terms low potency and high potency refer only to the milligram doses used for these medicines and not to any difference in effectiveness (e.g., 100 mg of chlorpromazine, a low-potency drug, is equivalent in antipsychotic activity to 2 mg of haloperidol, a high-potency drug). Chlorpromazine and thioridazine are low-potency drugs, whereas trifluoperazine, fluphenazine, thiothixene, haloperidol, and loxapine are high-potency drugs. Since 1990, antipsychotic medications have also been classified as typical (first-generation) antipsychotic agents or atypical (second-generation) antipsychotic agents on the basis of their mechanism of action (Table 18-1). The atypical antipsychotic agents are aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. All of the remaining antipsychotic agents listed in Table 18-1 are typical antipsychotic agents. The typical antipsychotic medications block the neurotransmitter dopamine in the central nervous system (CNS). The atypical antipsychotic agents block dopamine receptors, but they also block serotonin receptors to varying degrees. However, the exact mechanisms whereby these actions prevent psychotic symptoms are unknown. There is substantially more to the development of psychotic symptoms than elevated dopamine levels. There are at least five known types of dopamine receptors and several more types of serotonin receptors in various areas of the CNS. Antipsychotic medications also stimulate or block cholinergic, histaminic, nicotinic, alpha-adrenergic, and beta-adrenergic neurotransmitter receptors to varying degrees, accounting for many of the adverse effects of therapy. All antipsychotic medications are equal in efficacy when used in equipotent doses. There is some unpredictable variation among patients, however, and individual patients sometimes show a better response to particular drugs. In general, medication should be selected on the basis of the need to avoid certain adverse effects when dealing with concurrent medical or psychiatric disorders. Despite practice trends, no proof exists that agitation responds best to sedating drugs or that withdrawn patients respond best to nonsedating drugs. Medication history should be a major factor in drug selection. The final important factors in drug selection are the clinically important differences in the frequency of adverse effects. No single drug is least likely to cause all adverse effects; thus, individual response should be the best determinant of which drug is to be used. The atypical antipsychotic agents tend to be more effective in relieving the negative and cognitive symptoms associated with schizophrenia and treating refractory schizophrenia, and they have a much lower incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPSs) and hyperprolactinemia. The initial goals of antipsychotic therapy are calming the agitated patient who may be a physical threat to himself or herself or to others and beginning the treatment of the psychosis and thought disorder. Combined therapy with benzodiazepines (often lorazepam) and antipsychotic medications allows lower dosages of the antipsychotic medication to be used, reducing the risk of serious adverse effects more commonly seen with higher-dose therapy. Some therapeutic effects, such as reduced psychomotor agitation and insomnia, are observed within 1 week of therapy, but reductions in hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder often require 6 to 8 weeks of treatment to achieve the full therapeutic effect. Rapid increases in the dosing of antipsychotic medications will not reduce the antipsychotic response time. Patients, families, and the health care team must be informed about giving antipsychotic agents an adequate chance to work before unnecessarily escalating the dosage and increasing the risk of adverse effects.

Drugs Used for Psychoses

Objectives

Key Terms

) (p. 274)

) (p. 274)

) (p. 274)

) (p. 274)

) (p. 274)

) (p. 274)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 275)

) (p. 276)

) (p. 276)

) (p. 276)

) (p. 276)

) (p. 276)

) (p. 276)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 279)

) (p. 280)

) (p. 280)

) (p. 280)

) (p. 280)

Psychosis

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Treatment of Psychosis

Drug Therapy for Psychosis

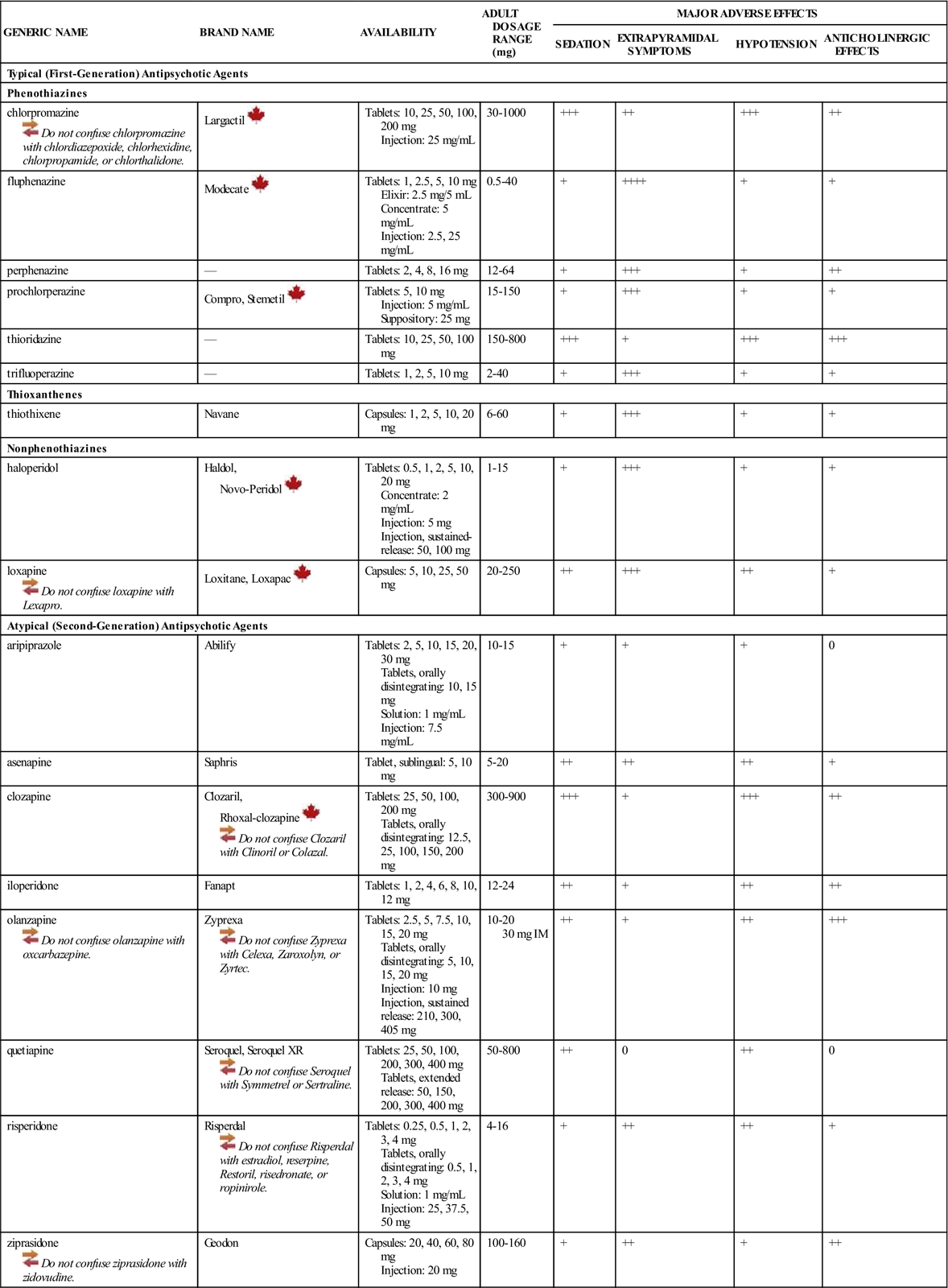

![]() Table 18-1

Table 18-1

GENERIC NAME

BRAND NAME

AVAILABILITY

ADULT DOSAGE RANGE (mg)

MAJOR ADVERSE EFFECTS

SEDATION

EXTRAPYRAMIDAL SYMPTOMS

HYPOTENSION

ANTICHOLINERGIC EFFECTS

Typical (First-Generation) Antipsychotic Agents

Phenothiazines

chlorpromazine ![]() Do not confuse chlorpromazine with chlordiazepoxide, chlorhexidine, chlorpropamide, or chlorthalidone.

Do not confuse chlorpromazine with chlordiazepoxide, chlorhexidine, chlorpropamide, or chlorthalidone.

Largactil ![]()

Tablets: 10, 25, 50, 100, 200 mg

Injection: 25 mg/mL

30-1000

+++

++

+++

++

fluphenazine

Modecate ![]()

Tablets: 1, 2.5, 5, 10 mg

Elixir: 2.5 mg/5 mL

Concentrate: 5 mg/mL

Injection: 2.5, 25 mg/mL

0.5-40

+

++++

+

+

perphenazine

—

Tablets: 2, 4, 8, 16 mg

12-64

+

+++

+

++

prochlorperazine

Compro, Stemetil ![]()

Tablets: 5, 10 mg

Injection: 5 mg/mL

Suppository: 25 mg

15-150

+

+++

+

+

thioridazine

—

Tablets: 10, 25, 50, 100 mg

150-800

+++

+

+++

+++

trifluoperazine

—

Tablets: 1, 2, 5, 10 mg

2-40

+

+++

+

+

Thioxanthenes

thiothixene

Navane

Capsules: 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 mg

6-60

+

+++

+

+

Nonphenothiazines

haloperidol

Haldol,

Novo-Peridol ![]()

Tablets: 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 mg

Concentrate: 2 mg/mL

Injection: 5 mg

Injection, sustained-release: 50, 100 mg

1-15

+

+++

+

+

loxapine ![]() Do not confuse loxapine with Lexapro.

Do not confuse loxapine with Lexapro.

Loxitane, Loxapac ![]()

Capsules: 5, 10, 25, 50 mg

20-250

++

+++

++

+

Atypical (Second-Generation) Antipsychotic Agents

aripiprazole

Abilify

Tablets: 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 mg

Tablets, orally disintegrating: 10, 15 mg

Solution: 1 mg/mL

Injection: 7.5 mg/mL

10-15

+

+

+

0

asenapine

Saphris

Tablet, sublingual: 5, 10 mg

5-20

++

++

++

+

clozapine

Clozaril,

Rhoxal-clozapine ![]()

![]() Do not confuse Clozaril with Clinoril or Colazal.

Do not confuse Clozaril with Clinoril or Colazal.

Tablets: 25, 50, 100, 200 mg

Tablets, orally disintegrating: 12.5, 25, 100, 150, 200 mg

300-900

+++

+

+++

++

iloperidone

Fanapt

Tablets: 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 mg

12-24

++

+

++

++

olanzapine ![]() Do not confuse olanzapine with oxcarbazepine.

Do not confuse olanzapine with oxcarbazepine.

Zyprexa ![]() Do not confuse Zyprexa with Celexa, Zaroxolyn, or Zyrtec.

Do not confuse Zyprexa with Celexa, Zaroxolyn, or Zyrtec.

Tablets: 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, 20 mg

Tablets, orally disintegrating: 5, 10, 15, 20 mg

Injection: 10 mg

Injection, sustained release: 210, 300, 405 mg

10-20

30 mg IM

++

+

++

+++

quetiapine

Seroquel, Seroquel XR ![]() Do not confuse Seroquel with Symmetrel or Sertraline.

Do not confuse Seroquel with Symmetrel or Sertraline.

Tablets: 25, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400 mg

Tablets, extended release: 50, 150, 200, 300, 400 mg

50-800

++

0

++

0

risperidone

Risperdal ![]() Do not confuse Risperdal with estradiol, reserpine, Restoril, risedronate, or ropinirole.

Do not confuse Risperdal with estradiol, reserpine, Restoril, risedronate, or ropinirole.

Tablets: 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4 mg

Tablets, orally disintegrating: 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4 mg

Solution: 1 mg/mL

Injection: 25, 37.5, 50 mg

4-16

+

++

++

+

ziprasidone ![]() Do not confuse ziprasidone with zidovudine.

Do not confuse ziprasidone with zidovudine.

Geodon

Capsules: 20, 40, 60, 80 mg

Injection: 20 mg

100-160

+

++

+

++

Actions

Uses

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree