Behavioral system model

Bonnie Holaday

“All of us, scientists and practicing professionals, must turn our attention to practice and ask questions of that practice. We must be inquisitive and inquiring, seeking the fullest and truest possible understanding of the theoretical and practical problems we encounter”

Dorothy E. Johnson

1919 to 1999

Credentials and background of the theorist

Dorothy E. Johnson was born on August 21, 1919, in Savannah, Georgia. She received her A.A. from Armstrong Junior College in Savannah, Georgia (1938), her B.S.N, from Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee (1942), and her M.P.H. from Harvard University in Boston (1948).

Previous authors: Victoria M. Brown, Sharon S. Conner, Linda S. Harbour, Jude A. Magers, and Judith K. Watt.

Johnson’s professional experiences involved mostly teaching, although she was a staff nurse at the Chatham-Savannah Health Council from 1943 to 1944. She was an instructor and an assistant professor in pediatric nursing at Vanderbilt University School of Nursing. From 1949 until her retirement in 1978 and her subsequent move to Key Largo, Florida, Johnson was an assistant professor of pediatric nursing, an associate professor of nursing, and a professor of nursing at the University of California in Los Angeles.

In 1955 and 1956, Johnson was a pediatric nursing advisor assigned to the Christian Medical College School of Nursing in Vellore, South India. From 1965 to 1967, she served as chairperson on the committee of the California Nurses Association that developed a position statement on specifications for the clinical specialist. Johnson’s publications include four books, more than 30 articles in periodicals, and many papers, reports, proceedings, and monographs (Johnson, 1980).

Of the many honors she received, Johnson (personal communication, 1984) was proudest of the 1975 Faculty Award from graduate students, the 1977 Lulu Hassenplug Distinguished Achievement Award from the California Nurses Association, and the 1981 Vanderbilt University School of Nursing Award for Excellence in Nursing. She died in February 1999 at 80 years of age. She was pleased that her Behavioral System Model had been found useful in furthering the development of a theoretical basis for nursing and was being used as a model for nursing practice on an institution-wide basis, but she reported that her greatest source of satisfaction came from following the productive careers of her students (D. Johnson, personal communication, 1996).

Theoretical sources

Johnson’s Behavioral System Model (JBSM) was heavily influenced by Florence Nightingale’s book, Notes on Nursing (Johnson, 1992). Johnson began her work on the model with the premise that nursing was a profession that made a distinctive contribution to the welfare of society. Thus, nursing had an explicit goal of action in patient welfare. Her task was to clarify the social mission of nursing from the “perspective of a theoretically sound view of the person we serve” (Johnson, 1977). She accepted Nightingale’s belief that the first concern of nursing is with the “relationship between the person who is ill and their environment, not with the illness” (Johnson, 1977). Johnson (1977) noted that the “transition from this approach to the more sophisticated and theoretically sounder behavioral system orientation took only a few years and was supported by both my own, and that of many colleagues, growing knowledge about man’s action systems and by the rapidly increasing knowledge about behavioral systems.” Johnson (1977) came to conceive of nursing’s specific contribution to patient welfare as that of fostering “efficient and effective behavioral functioning in the person, both to prevent illness and during and following illness.”

Johnson used the work of behavioral scientists in psychology, sociology, and ethnology to develop her theory. The interdisciplinary literature that Johnson cited focused on observable behaviors that were of adaptive significance. This body of literature influenced the identification and the content of her seven subsystems. Talcott Parsons is acknowledged specifically in early developmental writings presenting concepts of the Johnson Behavioral System Model (Johnson, 1961b). Parsons’ (1951; 1964) social action theory stressed a structural-functional approach. One of his major contributions was to reconcile functionalism (the idea that every observable social behavior has a function to perform) with structuralism (the idea that social behaviors, rather than being directly functional, are expressions of deep underlying structures in social systems). Thus, structures (social systems) and all behaviors have a function in maintaining them. The components of the structure of a social system—goal, set, choice and behavior—are the same in Parsons’ and Johnson’s theories.

Johnson also relied heavily on system theory and used concepts and definitions from Rapoport, Chin, von Bertalanffy, and Buckley (Johnson, 1980). In system theory, as in Johnson’s theory, one of the basic assumptions embraces the concept of order. Another is that a system is a set of interacting units that form a whole intended to perform some function. Johnson conceptualized the person as a behavioral system in which the behavior of the individual as a whole is the focus. It is the focus on what the individual does and why. One of the strengths of the JBS theory is the consistent integration of concepts defining behavioral systems drawn from general systems theory. Some of these concepts include: holism, goal seeking, interrelationship/interdependency, stability, instability, subsystems, regularity, structure, function, energy, feedback, and adaptation.

Johnson noted that although the literature indicates that others support the idea that a person is a behavioral system and that a person’s specific response patterns form an organized and integrated whole, the idea was original with her as far as she knew. Just as the development of knowledge of the whole biological system was preceded by knowledge of the parts, the development of knowledge of behavioral systems was focused on specific behavioral responses. Empirical literature supporting the notion of the behavioral system as a whole and its usefulness as a framework for nursing decisions in research, education, and nursing practice has accumulated since it was introduced (Benson, 1997; Derdiarian, 1991; Grice, 1997; Holaday, 1981, 1982; Lachicotte & Alexander, 1990; Martha, Bhaduri, & Jain, 2004; Poster, Dee, & Randell, 1997; Turner-Henson, 1992; Wilkie, 1990; Wilmoth & Ross, 1997; Wilmouth, 2007; Wang & Palmer, 2010).

Developing the Behavioral System Model from a philosophical perspective, Johnson (1980) wrote that nursing contributes by facilitating effective behavioral functioning in the patient before, during, and after illness. She used concepts from other disciplines, such as social learning, motivation, sensory stimulation, adaptation, behavioral modification, change process, tension, and stress to expand her theory for the practice of nursing.

Use of empirical evidence

The empirical origins of this theory begin with Johnson’s use of systems thinking (synthesis). This process concentrates on the function and behavior of the whole and is focused on understanding and explanation of the behavioral system. Johnson’s work on the Behavioral System Model corresponded with the “systems age.” Buckley’s (1968) seminal text was published the same year Johnson formally presented her theory at Vanderbilt University.

System theory, as a basic science, deals on an abstract level with the general properties of systems regardless of physical form or domain of application. General System Theory was founded on the assumption that all kinds of systems had characteristics in common regardless of their internal nature. Johnson used General System Theory and systems thinking to bring together a body of theoretical constructs, as well as explaining their interrelationships, to identify and describe the mission of nursing. The JBSM provided a framework that is based on her synthesis of the component parts of this system and a description of the context of relationships with each other (subsystems) and with other systems (environment). Standing in contrast to scientific reductionism, Johnson proposed to view nursing in a holistic manner—a behavioral system. Consistent with system theory, the JBSM provides an understanding of a system by examining the linkages and interactions between the elements that compose the entirety of the system. The paragraphs that follow describe how Johnson incorporated empirical knowledge from other disciplines into the JBSM.

Concepts Johnson identified and defined in her theory are supported in the literature. She noted that Leitch and Escolona agree that tension produces behavioral changes and that the manifestation of tension by an individual depends on both internal and external factors (Johnson, 1980). Johnson (1959b) used the work of Selye, Grinker, Simmons, and Wolff to support the idea that specific patterns of behavior are reactions to stressors from biological, psychological, and sociological sources, respectively. Johnson (1961a) suggested a difference in her model from Selye’s conception of stress. Johnson’s concept of stress “follows rather closely Caudill’s conceptualization; that is, that stress is a process in which there is interplay between various stimuli and the defenses erected against them. Stimuli may be positive in that they are present, or negative in that something desired or required is absent” (Johnson, 1961a, pp. 7–8). Selye “conceives stress as ‘a state manifested by the specific syndrome which consists of all the nonspecifically induced changes within a biologic system” (Johnson, 1961a, p. 8).

In Conceptual Models for Nursing Practice, Johnson (1980) described seven subsystems that make up her behavioral system. To support the attachment-affiliative subsystem, she cited the work of Ainsworth and Robson. Heathers, Gerwitz, and Rosenthal have described and explained dependency behavior, another subsystem defined by Johnson. The response systems of ingestion and elimination, as described by Walike, Mead, and Sears, are also parts of Johnson’s behavioral system. The work of Kagan and Resnik were used to support the sexual subsystem. The aggressive-protective subsystem, which functions to protect and preserve, is supported by Lorenz and Feshbach (Feshbach, 1970; Johnson, 1980; Lorenz, 1966). According to Atkinson, Feather, and Crandell, physical, creative, mechanical, and social skills are manifested by achievement behavior, another subsystem identified by Johnson (1980).

The restorative subsystem was developed by faculty and clinicians in order to include behaviors such as sleep, play, and relaxation (Grubbs, 1980). Although Johnson (personal communication, 1996) agreed that “there may be more or fewer subsystems” than originally identified, she did not support restorative as a subsystem of the Behavioral System Model. She believed that sleep is primarily a biological force, not a motivational behavior. She suggested that many of the behaviors identified in infants during their first years of life, such as play, are actually achievement behaviors. Johnson (personal communication, 1996) stated that there was a need to examine the possibility of an eighth subsystem that addresses explorative behaviors; further investigation may delineate it as a subsystem separate from the achievement subsystem.

Major assumptions

Nursing

Nursing’s goal is to maintain and restore the person’s behavioral system balance and stability or to help the person achieve a more optimum level of balance and functioning. Thus, nursing, as perceived by Johnson, is an external force acting to preserve the organization and integration of the patient’s behavior to an optimal level by means of imposing temporary regulatory or control mechanisms or by providing resources while the patient is experiencing stress or behavioral system imbalance (Brown, 2006). An art and a science, nursing supplies external assistance both before and during system balance disturbance and therefore requires knowledge of order, disorder, and control (Herbert, 1989; Johnson, 1980). Nursing activities do not depend on medical authority, but they are complementary to medicine.

Person

Johnson (1980) viewed the person as a behavioral system with patterned, repetitive, and purposeful ways of behaving that link the person with the environment. The conception of the person is basically a motivational one. This view leans heavily on Johnson’s acceptance of ethology theories, that innate, biological factors influence the patterning and motivation of behavior. She also acknowledged that prior experience, learning, and physical and social stimuli also influence behavior. She noted that a prerequisite to using this model is the ability to look at a person as a behavioral system, observe a collection of behavioral subsystems, and be knowledgeable about the physiologic, psychological, and sociocultural factors operating outside them (Class notes, 1971).

Johnson identified several assumptions that are critical to understanding the nature and operation of the person as a behavioral system. We assume that there is organization, interaction, and interdependency and integration of the parts of behavior that make up the system. An individual’s specific response patterns form an organized and integrated whole. The interrelated and interdependent parts are called subsystems. Johnson (1977) further assumed that the behavioral system tends to achieve balance among the various forces operating within and upon it. People strive continually to maintain a behavioral system balance and steady states by more or less automatic adjustments and adaptations to the natural forces impinging upon them. Johnson also recognized that people actively seek new experiences that may temporarily disturb balance.

Johnson further (1977, 1980) assumed that a behavioral system, which both requires and results in some degree of regularity and constancy in behavior, is essential to human beings. Finally, Johnson (1977) assumed that behavioral system balance reflected adjustments and adaptations by the person that are successful in some way and to some degree. This will be true, even though the observed behavior may not always match the cultural norms for acceptable or health behavior.

Balance is essential for effective and efficient functioning of the person. Balance is developed and maintained within the subsystems(s) or the system as a whole. Changes in the structure or function of a system are related to problems with drive, lack of functional requirements/sustenal imperatives, or a change in the environment. A person’s attempt to reestablish balance may require an extraordinary expenditure of energy that leaves a shortage of energy to assist biological processes and recovery.

Health

Johnson perceived health as an elusive, dynamic state influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors. Health is reflected by the organization, interaction, interdependence, and integration of the subsystems of the behavioral system (Johnson, 1980). An individual attempts to achieve a balance in this system, which will lead to functional behavior. A lack of balance in the structural or functional requirements of the subsystems leads to poor health. Thus, when evaluating “health,” one focuses on the behavioral system and system balance and stability, effective and efficient functioning, and behavioral system imbalance and instability. The outcomes of behavior system balance are: (1) a minimum expenditure of energy is required (implying more energy is available to maintain health, or, in the case of illness, energy is available for the biological processes needed for recovery); (2) continued biologic and social survival are ensured; and (3) some degree of personal satisfaction accrues (Grubbs, 1980; Johnson 1980).

Environment

In Johnson’s theory, the environment consists of all the factors that are not part of the individual’s behavioral system, but that influence the system. The nurse may manipulate some aspects of the environment so the goal of health or behavioral system balance can be achieved for the patient (Brown, 2006).

The behavioral system “determines and limits the interaction between the person and their environment and establishes the relationship of the person to the objects, events and situations in the environment” (Johnson 1978). Such behavior is orderly and predictable. It is maintained because it has been functionally efficient and effective most of the time in managing the person’s relationship to the environment. It changes when this is no longer the case, or when the person desires a more optimum level of functioning. The behavioral system has many tasks and missions to perform in maintaining its own integrity and in managing the system’s relationship to its environment.

The behavioral system attempts to maintain equilibrium in response to environmental factors by adjusting and adapting to the forces that impinge on it. Excessively strong environmental forces disturb the behavioral system balance and threaten the person’s stability. An unusual amount of energy is required to the system to reestablish equilibrium in the fact of continuing forces (Loveland-Cherry & Wilkerson, 1983).

The environment is also the source of the sustenal imperatives of protection, nurturance, and stimulation that are necessary prerequisites to maintaining health (behavioral system balance) (Grubbs, 1980). When behavioral system imbalance (disequilibrium) occurs, the nurse may need to become the temporary regulator of the environment and provide the person’s supply of functional requirements so the person can adapt to stressors. The type and the amount of functional requirements needed vary by age, gender, culture, coping ability, and type and severity of illness.

Theoretical assertions

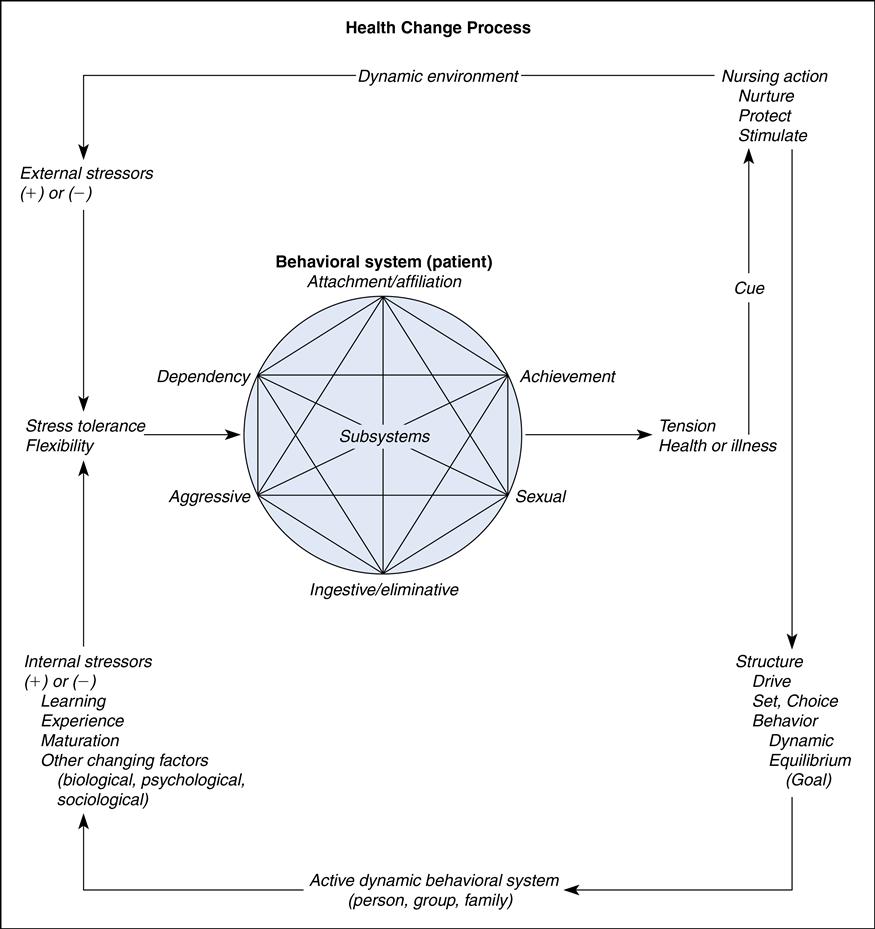

The Johnson Behavioral System Theory addresses the metaparadigm concepts of person, environment, and nursing. The person is a behavioral system with seven interrelated subsystems (Figure 18–1). Each subsystem is formed of a set of behavioral responses, or responsive tendencies, or action systems that share a common drive or goal. Organized around drives, (some type of intraorganismic motivational structure), these responses are differentiated, developed, and modified over time through maturation, experience, and learning. They are determined developmentally and are continuously governed by a multitude of physical, biological, and psychological factors operating in a complex and interlocking fashion.

Each subsystem is described and analyzed in terms of structural and functional requirements. The four structural elements that have been identified include the following: (1) drive or goal—the ultimate consequence of behaviors in it; (2) set—a tendency or predisposition to act in a certain way. Set is subdivided into two types—preparatory or what a person usually attends to, and perseverative, the habits one maintains in a situation; (3) choice represents the behavior a patient sees himself or herself as being able to use in any given situation; and (4) action or the behavior of an individual (Grubbs, 1980; Johnson, 1980). Set will play a major role both in the choices a person considers and in their ultimate behavior. Each of the seven subsystems has the same three functional requirements: (1) protection, (2) nurturance, and (3) stimulation. These functional requirements must be met through the person’s own efforts, or with the outside assistance of the nurse. For the subsystems to develop and maintain stability, each must have a constant supply of functional requirements that are usually supplied by the environment. However, during illness or when the potential for illness poses a threat, the nurse may become a source of functional requirements.

The responses by the subsystems are developed through motivation, experience, and learning and are influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors (Johnson, 1980). The behavioral system attempts to achieve balance by adapting to internal and environmental stimuli. The behavioral system is made up of “all the patterned, repetitive, and purposeful ways of behaving that characterize each man’s life” (Johnson, 1980, p. 209). This functional unit of behavior “determines and limits the interaction of the person and his environment and establishes the relationship of the person with the objects, events, and situations in his environment” (Johnson, 1980, p. 209). “The behavioral system manages its relationship with its environment” (Johnson, 1980, p. 209). The behavioral system appears to be active and not passive. The nurse is external to and interactive with the behavioral system.

Successful use of the Johnson’s Behavioral System Theory in clinical practice requires the incorporation of the nursing process. The clinician must develop an assessment instrument that incorporates the components of the theory so they are able to assess the patient as a behavioral system to determine if there is an actual or perceived threat of illness, and to determine the person’s ability to adapt to illness or threat of illness without developing behavioral system imbalance. This means developing appropriate questions and observations for each of the behavioral subsystems.

A state of instability in the behavioral system results in a need for nursing intervention. Identification of the source of the problem in the system leads to appropriate nursing action that results in the maintenance or restoration of behavioral system balance (Brown, 2006). Nursing interventions can be in such general forms as: (1) repairing structural units; (2) temporarily imposing external regulatory or control measures; (3) supplying environmental conditions or resources; or (4) providing stimulation to the extent that any problem can be anticipated, and preventive nursing action is in order (Johnson, 1978). “If the source of the problem has a structural stressor, the nurse will focus on either the goal, set, choice, or action of the subsystem. If the problem is one of function, the nurse will focus on the source and sufficiency of the functional requirements since functional problems originate from an environmental excess or deficiency” (Grubbs, 1980, p. 242). The goal of nursing is to maintain or restore the person’s behavioral system balance and stability or to help the person achieve a more optimum level of behavioral system functioning when this is desired and possible (Johnson, 1978).

Logical form

Johnson approached the task of delineating nursing’s mission from historical, analytical, and empirical perspectives. Deductive and inductive thinking is evident throughout the process of developing the Johnson behavioral system theory. A system, inasmuch as it is a whole, will lose its synergetic properties if it is decomposed. Understanding must therefore progress from the whole to its parts—a synthesis. Johnson first identified the behavioral system and then explained the properties and behavior of the system. Finally, she explained the properties and behavior of the subsystems as a part or function of the system. The analysis gave us description and knowledge, while the systems thinking (synthesis) gave us explanation and understanding.

Acceptance by the nursing community

Practice

The utility of the Johnson Behavioral System Theory is evident from the variety of clinical settings and age groups where the theory has been used. It has been used in inpatient, outpatient, and community settings as well as in nursing administration. It has been used with a variety of client populations, and several practice tools have been developed (Fawcett, 2005).

Johnson does not use the term nursing process. Assessment, disorders, treatment,and evaluation are concepts referred to in a variety of Johnson’s works. “For the practitioner, conceptual models provide a diagnostic and treatment orientation, and thus are of considerable practical import” (Johnson, 1968, p. 2). The nursing process becomes applicable in the Behavioral System Model when behavioral malfunction occurs “that is in part disorganized, erratic, and dysfunctional. Illness or other sudden internal or external environmental change is most frequently responsible for such malfunctions” (Johnson, 1980, p. 212). “Assistance is appropriate at those times the individual is experiencing stress of a health-illness nature which disturbs equilibrium, producing tension” (Johnson, 1961a, p. 6). However, it is important to note that systems analysis is an important component of system theory. One monitors outputs from a given subsystem in order to monitor performance. Signs of disequilibrium require one to identify the problem, further define the problem by gathering data, and design an intervention to restore equilibrium/balance (Miller, 1965; Jenkins, 1969).

Johnson (1959a) implied that the initial nursing assessment begins when the cue tension is observed and signals disequilibrium. Sources for assessment data can be through history taking, testing, and structural observations (Johnson, 1980). “The behavioral system is thought to determine and limit the interaction between the person and his environment” (Johnson, 1968, p. 3). This suggests that the accuracy and quantity of the data obtained during nursing assessment are not controlled by the nurse, but by the patient (system). The only observed part of the subsystem’s structure is behavior. Six internal and external regulators have been identified that “simultaneously influence and are influenced by behavior” including biophysical, psychological, developmental, sociocultural, family, and physical environmental regulators (Randell, 1991, p. 157).

The nurse must be able to access information related to goals, sets, and choices that make up the structural subsystems. “One or more of [these] subsystems is likely to be involved in any episode of illness, whether in an antecedent or a consequential way or simply in association, directly or indirectly with the disorder or its treatment” (Johnson, 1968, p. 3). Accessing the data is critical to accurate statement of the disorder.

Johnson did not define specific disorders, but she did state two general categories of disorders on the basis of the relationship to the biological system (Johnson, 1968).

Disorders are those which are related tangentially or peripherally to disorder in the biological system; that is, they are precipitated simply by the fact of illness or the situational context of treatment; and…those [disorders] which are an integral part of a biological system disorder in that they are either directly associated with or a direct consequence of a particular kind of biological system disorder or its treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree