Kenneth D. Phillips and Robin Harris

Adaptation model

“God is intimately revealed in the diversity of creation and is the common destiny of creation; persons use human creative abilities of awareness, enlightenment, and faith; and persons are accountable for the process of deriving, sustaining, and transforming the universe”

(Roy, 2000, p. 127).

Sister Callista Roy

1939 to present

Credentials and background of the theorist

Sister Callista Roy, a member of the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Carondelet, was born on October 14, 1939, in Los Angeles, California. She received a bachelor’s degree in nursing in 1963 from Mount Saint Mary’s College in Los Angeles and a master’s degree in nursing from the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1966. After earning her nursing degrees, Roy began her education in sociology, receiving both a master’s degree in sociology in 1973 and a doctorate degree in sociology in 1977 from the University of California.

Previous authors: Kenneth D. Phillips, Carolyn L. Blue, Karen M. Brubaker, Julia M. B. Fine, Martha J. Kirsch, Katherine R. Papazian, Cynthia M. Riester, and Mary Ann Sobiech. The author wishes to express appreciation to Sister Callista Roy for critiquing the chapter.

While working toward her master’s degree, Roy was challenged in a seminar with Dorothy E. Johnson to develop a conceptual model for nursing. While working as a pediatric staff nurse, Roy had noticed the great resiliency of children and their ability to adapt in response to major physical and psychological changes. Roy was impressed by adaptation as an appropriate conceptual framework for nursing. Roy developed the basic concepts of the model while she was a graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles, from 1964 to 1966. Roy began operationalizing her model in 1968 when Mount Saint Mary’s College adopted the adaptation framework as the philosophical foundation of the nursing curriculum. The Roy Adaptation Model was first presented in the literature in an article published in Nursing Outlook in 1970 entitled “Adaptation: A Conceptual Framework for Nursing” (Roy, 1970).

Roy was an associate professor and chairperson of the Department of Nursing at Mount Saint Mary’s College until 1982. She was promoted to the rank of professor in 1983 at both Mount Saint Mary’s College and the University of Portland. She helped initiate and taught in a summer master’s program at the University of Portland. From 1983 to 1985, she was a Robert Wood Johnson postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, San Francisco, as a clinical nurse scholar in neuroscience. During this time, she conducted research on nursing interventions for cognitive recovery in head injuries and on the influence of nursing models on clinical decision making. In 1987, Roy began the newly created position of nurse theorist at Boston College School of Nursing.

Roy has published many books, chapters, and periodical articles and has presented numerous lectures and workshops focusing on her nursing adaptation theory (Roy & Andrews, 1991). The refinement and restatement of the Roy Adaptation Model is published in her 1999 book, The Roy Adaptation Model (Roy & Andrews, 1999).

Roy is a member of Sigma Theta Tau, and she received the National Founder’s Award for Excellence in Fostering Professional Nursing Standards in 1981. Her achievements include an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from Alverno College (1984), honorary doctorates from Eastern Michigan University (1985) and St. Joseph’s College in Maine (1999), and an American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year Award for Essentials of the Roy Adaptation Model (Andrews & Roy, 1986). Roy has been recognized as the World Who’s Who of Women (1979); Personalities of America (1978); fellow of the American Academy of Nursing (1978); recipient of a Fulbright Senior Scholar Award from the Australian-American Educational Foundation (1989), ) and received the Martha Rogers Award for Advancing Nursing Science from the National League for Nursing (1991). Roy received the Outstanding Alumna award and the prestigious Carondelet Medal from her alma mater, Mount Saint Mary’s. The American Academy of Nursing honored Roy for her extraordinary life achievements by recognizing her as a Living Legend (2007).

Theoretical sources

Derivation of the Roy Adaptation Model for nursing included a citation of Harry Helson’s work in psychophysics that extended to social and behavioral sciences (Roy, 1984). In Helson’s adaptation theory, adaptive responses are a function of the incoming stimulus and the adaptive level (Roy, 1984). A stimulus is any factor that provokes a response. Stimuli may arise from the internal or the external environment (Roy, 1984). The adaptation level is made up of the pooled effect of the following three classes of stimuli:

1. Focal stimuli immediately confront the individual.

3. Residual stimuli are environmental factors of which the effects are unclear in a given situation.

Helson’s work developed the concept of the adaptation level zone, which determines whether a stimulus will elicit a positive or negative response. According to Helson’s theory, adaptation is the process of responding positively to environmental changes (Roy & Roberts, 1981).

Roy (Roy & Roberts, 1981) combined Helson’s work with Rapoport’s definition of system to view the person as an adaptive system. With Helson’s adaptation theory as a foundation, Roy (1970) developed and further refined the model with concepts and theory from Dohrenwend, Lazarus, Mechanic, and Selye. Roy gave special credit to co-authors Driever, for outlining subdivisions of self-integrity, and Martinez and Sato, for identifying common and primary stimuli affecting the modes. Other co-workers also elaborated the concepts. Poush-Tedrow and Van Landingham made contributions to the interdependence mode, and Randell made contributions to the role function mode.

After the development of her model, Roy presented it as a framework for nursing practice, research, and education. Roy (1971) acknowledged that more than 1500 faculty and students contributed to the theoretical development of the adaptation model. She presented the model as a curriculum framework to a large audience at the 1977 Nurse Educator Conference in Chicago (Roy, 1979). And, by 1987, it was estimated that more than 100,000 nurses in the United States and Canada had been prepared to practice using the Roy model.

In Introduction to Nursing: An Adaptation Model, Roy (1976a) discussed self-concept and group identity mode. She and her collaborators cited the work of Coombs and Snygg regarding self-consistency and major influencing factors of self-concept (Roy, 1984). Social interaction theories are cited to provide a theoretical basis. For example, Roy (1984) notes that Cooley (1902) theorizes that self-perception is influenced by perceptions of others’ responses, termed the “looking glass self.” She points out that Mead expands the idea by hypothesizing that self-appraisal uses the generalized other. Roy builds on Sullivan’s suggestion that self arises from social interaction (Roy, 1984). Gardner and Erickson support Roy’s developmental approaches (Roy, 1984). The other modes—physiological-physical, role function, and interdependence—were drawn similarly from biological and behavioral sciences for an understanding of the person.

Additional development of the model occurred during the later 1900s and into the twenty-first century. These developments included updated scientific and philosophical assumptions; a redefinition of adaptation and adaptation levels; extension of the adaptive modes to group-level knowledge development; and analysis, critique, and synthesis of the first 25 years of research based on the Roy Adaptation Model. Roy agrees with other theorists who believe that changes in the person-environment systems of the earth are so extensive that a major epoch is ending (Davies, 1988; De Chardin, 1966). During the 67 million years of the Cenozoic era, the Age of Mammals and an era of great creativity, human life appeared on Earth. During this era, humankind has had little or no influence on the universe (Roy, 1997). “As the era closes, humankind has taken extensive control of the life systems of the earth. Roy claims that we are now in the position of deciding what kind of universe we will inhabit” (Roy, 1997, p. 42). Roy “has made the foci of assumptions of the twenty-first century mutual complex person and environment self-organization and a meaningful destiny of convergence of the universe, persons, and environment in what can be considered a supreme being or God” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 395). According to Roy (1997), “persons are coextensive with their physical and social environments” (p. 43) and they “share a destiny with the universe and are responsible for mutual transformations” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 395). Developments of the model that were related to the integral relationship between person and environment have been influenced by Pierre Teilhard De Chardin’s law of progressive complexity and increasing consciousness (De Chardin, 1959, 1965, 1966, 1969) and the work of Swimme and Berry (1992).

Use of empirical evidence

From this beginning, the Roy Adaptation Model has been supported through research in practice and in education (Brower & Baker, 1976; Farkas, 1981; Mastal & Hammond, 1980; Meleis, 1985, 2007; Roy, 1980; Roy & Obloy, 1978; Wagner, 1976). In 1999 (Roy & Andrews, 1999), a group of seven scholars working with Roy conducted a meta-analysis, critique, and synthesis of 163 studies based on the Roy Adaptation Model that had been published in 44 English language journals on five continents and dissertations and theses from the United States. Of these 163 studies, 116 met the criteria established for testing propositions from the model. Twelve generic propositions based on Roy’s earlier work were derived. To synthesize the research, findings of each study were used to state ancillary and practice propositions, and support for the propositions was examined. Of 265 propositions tested, 216 (82%) were supported. Roy (2011a) presented a comprehensive review of research based on the adaptation model for the last 25 years in Nursing Science Quarterly, volume 24, number 4. The complete issue is dedicated to honoring Callista Roy and her life work.

Major assumptions

Assumptions from systems theory and assumptions from adaptation level theory have been combined into a single set of scientific assumptions. From systems theory, human adaptive systems are viewed as interactive parts that act in unity for some purpose. Human adaptive systems are complex and multifaceted and respond to a myriad of environmental stimuli to achieve adaptation. With their ability to adapt to environmental stimuli, humans have the capacity to create changes in the environment (Roy & Andrews, 1999). Drawing on characteristics of creation spirituality by Swimme and Berry (1992), Roy combined the assumptions of humanism and veritivity into a single set of philosophical assumptions. Humanism asserts that the person and human experiences are essential to knowing and valuing, and that they share in creative power. Veritivity affirms the belief in the purpose, value, and meaning of all human life. These scientific and philosophical assumptions have been refined for use of the model in the twenty-first century (Box 17–1).

Adaptation

Roy has further defined adaptation for use in the twenty-first century (Roy & Andrews, 1999). According to Roy, adaptation refers to “the process and outcome whereby thinking and feeling persons, as individuals or in groups, use conscious awareness and choice to create human and environmental integration” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 30). Rather than being a human system that simply strives to respond to environmental stimuli to maintain integrity, every human life is purposeful in a universe that is creative, and persons are inseparable from their environment.

Nursing

Roy defines nursing broadly as a “health care profession that focuses on human life processes and patterns and emphasizes promotion of health for individuals, families, groups, and society as a whole” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 4). Specifically, Roy defines nursing according to her model as the science and practice that expands adaptive abilities and enhances person and environmental transformation. She identifies nursing activities as the assessment of behavior and the stimuli that influence adaptation. Nursing judgments are based on this assessment, and interventions are planned to manage the stimuli (Roy & Andrews, 1999). Roy differentiates nursing as a science from nursing as a practice discipline. Nursing science is… “a developing system of knowledge about persons that observes, classifies, and relates the processes by which persons positively affect their health status” (Roy, 1984, pp. 3–4). Nursing as a practice discipline is “nursing’s scientific body of knowledge used for the purpose of providing an essential service to people, that is, promoting ability to affect health positively” (Roy, 1984, pp. 3–4). “Nursing acts to enhance the interaction of the person with the environment—to promote adaptation” (Andrews & Roy, 1991, p. 20).

Roy’s goal of nursing is “the promotion of adaptation for individuals and groups in each of the four adaptive modes, thus contributing to health, quality of life, and dying with dignity” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 19). Nursing fills a unique role as a facilitator of adaptation by assessing behavior in each of these four adaptive modes and factors influencing adaptation and by intervening to promote adaptive abilities and to enhance environment interactions (Roy & Andrews, 1999).

Person

According to Roy, humans are holistic, adaptive systems. “As an adaptive system, the human system is described as a whole with parts that function as unity for some purpose. Human systems include people as individuals or in groups, including families, organizations, communities, and society as a whole” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 31). Despite their great diversity, all persons are united in a common destiny (Roy & Andrews, 1999). “Human systems have thinking and feeling capacities, rooted in consciousness and meaning, by which they adjust effectively to changes in the environment and, in turn, affect the environment” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 36). Persons and the earth have common patterns and mutuality of relations and meaning (Roy & Andrews, 1999). Roy (Roy & Andrews, 1999) defined the person as the main focus of nursing, the recipient of nursing care, a living, complex, adaptive system with internal processes (cognator and regulator) acting to maintain adaptation in the four adaptive modes (physiological, self-concept, role function, and interdependence).

Health

“Health is a state and a process of being and becoming integrated and a whole person. It is a reflection of adaptation, that is, the interaction of the person and the environment” (Andrews & Roy, 1991, p. 21). Roy (1984) derived this definition from the thought that adaptation is a process of promoting physiological, psychological, and social integrity, and that integrity implies an unimpaired condition leading to completeness or unity. In her earlier work, Roy viewed health along a continuum flowing from death and extreme poor health to high-level and peak wellness (Brower & Baker, 1976). During the late 1990s, Roy’s writings focused more on health as a process in which health and illness can coexist (Roy & Andrews, 1999). Drawing on the writings of Illich (1974, 1976), Roy wrote, “health is not freedom from the inevitability of death, disease, unhappiness, and stress, but the ability to cope with them in a competent way” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 52).

Health and illness is one inevitable, coexistent dimension of the person’s total life experience (Riehl & Roy, 1980). Nursing is concerned with this dimension. When mechanisms for coping are ineffective, illness is the result. Health ensues when humans continually adapt. As people adapt to stimuli, they are free to respond to other stimuli. The freeing of energy from ineffective coping attempts can promote healing and enhance health (Roy, 1984).

Environment

According to Roy, environment is “all the conditions, circumstances, and influences surrounding and affecting the development and behavior of persons or groups, with particular consideration of the mutuality of person and earth resources that includes focal, contextual, and residual stimuli” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 81). “It is the changing environment [that] stimulates the person to make adaptive responses” (Andrews & Roy, 1991, p. 18). Environment is the input into the person as an adaptive system involving both internal and external factors. These factors may be slight or large, negative or positive. However, any environmental change demands increasing energy to adapt to the situation. Factors in the environment that affect the person are categorized as focal, contextual, and residual stimuli.

Theoretical assertions

Roy’s model focuses on the concept of adaptation of the person. Her concepts of nursing, person, health, and environment are all interrelated to this central concept. The person continually experiences environmental stimuli. Ultimately, a response is made and adaptation occurs. This response may be either an adaptive or an ineffective response. Adaptive responses promote integrity and help the person to achieve the goals of adaptation, that is, they achieve survival, growth, reproduction, mastery, and person and environmental transformations. Ineffective responses fail to achieve or threaten the goals of adaptation. Nursing has a unique goal to assist the person’s adaptation effort by managing the environment. The result is attainment of an optimal level of wellness by the person (Andrews & Roy, 1986; Randell, Tedrow, & Van Landingham, 1982; Roy, 1970, 1971, 1980, 1984; Roy & Roberts, 1981).

As an open living system, the person receives inputs or stimuli from both the environment and the self. The adaptation level is determined by the combined effect of focal, contextual, and residual stimuli. Adaptation occurs when the person responds positively to environmental changes. This adaptive response promotes the integrity of the person, which leads to health. Ineffective responses to stimuli lead to disruption of the integrity of the person (Andrews & Roy, 1986; Randell, Tedrow, & Van Landingham, 1982; Roy, 1970, 1971, 1980; Roy & McLeod, 1981).

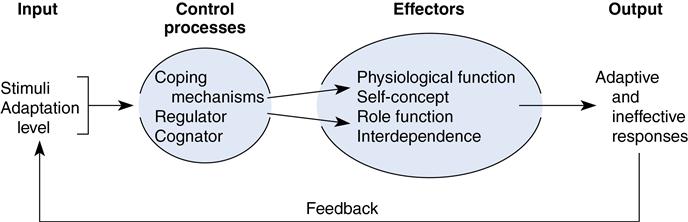

There are two interrelated subsystems in Roy’s model (Figure 17–1). The primary, functional, or control processes subsystem consists of the regulator and the cognator. The secondary, effector subsystem consists of the following four adaptive modes: (1) physiological needs, (2) self-concept, (3) role function, and (4) interdependence (Andrews & Roy, 1986; Limandri, 1986; Mastal, Hammond, & Roberts, 1982; Meleis, 1985, 2007; Riehl & Roy, 1980; Roy, 1971, 1975).

Roy views the regulator and the cognator as methods of coping. The regulator coping subsystem, by way of the physiological adaptive mode, “responds automatically through neural, chemical, and endocrine coping processes” (Andrews & Roy, 1991, p. 14). The cognator coping subsystem, by way of the self-concept, interdependence, and role function adaptive modes, “responds through four cognitive-emotive channels: perceptual information processing, learning, judgment, and emotion” (Andrews & Roy, 1991, p. 14). Perception is the interpretation of a stimulus, and perception links the regulator with the cognator in that “input into the regulator is transformed into perceptions. Perception is a process of the cognator. The responses following perception are feedback into both the cognator and the regulator” (Galligan, 1979, p. 67).

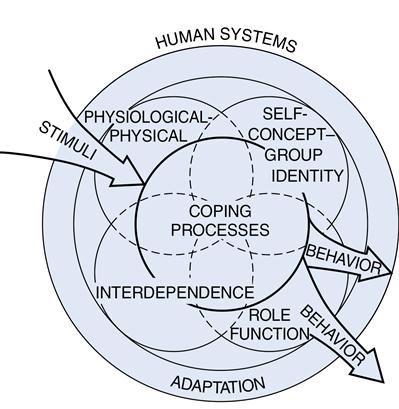

The four adaptive modes of the two subsystems in Roy’s model provide form or manifestations of cognator and regulator activity. Responses to stimuli are carried out through four adaptive modes. The physiological-physical adaptive mode is concerned with the way humans interact with the environment through physiological processes to meet the basic needs of oxygenation, nutrition, elimination, activity and rest, and protection. The self-concept group identity adaptive mode is concerned with the need to know who one is and how to act in society. An individual’s self-concept is defined by Roy as “the composite of beliefs or feelings that an individual holds about him- or herself at any given time” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 49). An individual’s self-concept is composed of the physical self (body sensation and body image) and the personal self (self-consistency, self-ideal, and moral-ethical-spiritual self). The role function adaptive mode describes the primary, secondary, and tertiary roles that an individual performs in society. A role describes the expectations about how one person behaves toward another person. The interdependence adaptive mode describes the interactions of people in society. The major task of the interdependence adaptive mode is for persons to give and receive love, respect, and value. The most important components of the interdependence adaptive mode are a person’s significant other (spouse, child, friend, or God) and his or her social support system. The purpose of the four adaptive modes is to achieve physiological, psychological, and social integrity. The four adaptive modes are interrelated through perception (Roy & Andrews, 1999) (Figure 17–2).

The person as a whole is made up of six subsystems. These subsystems (the regulator, the cognator, and the four adaptive modes) are interrelated to form a complex system for the purpose of adaptation. Relationships among the four adaptive modes occur when internal and external stimuli affect more than one mode, when disruptive behavior occurs in more than one mode, or when one mode becomes the focal, contextual, or residual stimulus for another mode (Brower & Baker, 1976; Chinn & Kramer, 2008; Mastal & Hammond, 1980).

With regard to human social systems, Roy broadly categorizes the control processes into the stabilizer and innovator subsystems. The stabilizer subsystem is analogous to the regulator subsystem of the individual and is concerned with stability. To maintain the system, the stabilizer subsystem involves organizational structure, cultural values, and regulation of daily activities of the system. The innovator subsystem is associated with the cognator subsystem of the individual and is concerned with creativity, change, and growth (Roy & Andrews, 1999).

Logical form

The Roy Adaptation Model of nursing is both deductive and inductive. It is deductive in that much of Roy’s theory is derived from Helson’s psychophysics theory. Helson developed the concepts of focal, contextual, and residual stimuli, which Roy (1971) redefined within nursing to form a typology of factors related to adaptation levels of persons. Roy also uses other concepts and theory outside the discipline of nursing and synthesizes these within her adaptation theory.

Roy’s adaptation theory is inductive in that she developed the four adaptive modes from research and nursing practice experiences of herself, her colleagues, and her students. Roy built on the conceptual framework of adaptation and developed a step-by-step model by which nurses use the nursing process to administer nursing care to promote adaptation in situations of health and illness (Roy, 1976a, 1980, 1984).

Acceptance by the nursing community

Practice

The Roy Adaptation Model is deeply rooted in nursing practice, and this, in part, contributes to its continued success (Fawcett, 2002). It remains one of the most frequently used conceptual frameworks to guide nursing practice, and it is used nationally and internationally (Roy & Andrews, 1999; Fawcett, 2005).

Roy’s model is useful for nursing practice, because it outlines the features of the discipline and provides direction for practice, education, and research. The model considers goals, values, the patient, and practitioner interventions. Roy’s nursing process is well developed. The two-level assessment assists in identification of nursing goals and diagnoses (Brower & Baker, 1976).

Early on, it was recognized as a valuable theory for nursing practice because of the goal that specified its aim for activity and a prescription for activities to realize the goal (Dickoff, James, & Wiedenbach, 1968a, 1968b). The goal of nursing and of the model is adaptation in four adaptive modes in a person’s health and illness. The prescriptive interventions are when the nurse manages stimuli by removing, increasing, decreasing, or altering them. These prescriptions may be found in the list of practice-related hypotheses generated by the model (Roy, 1984).

When using Roy’s six-step nursing process, the nurse performs the following six functions:

1. Assesses the behaviors manifested from the four adaptive modes

3. Makes a statement or nursing diagnosis of the person’s adaptive state

4. Sets goals to promote adaptation

5. Implements interventions aimed at managing the stimuli to promote adaptation

By manipulating the stimuli and not the patient, the nurse enhances “the interaction of the person with their environment, thereby promoting health” (Andrews & Roy, 1986, p. 51). The nursing process is well suited for use in a practice setting. The two-level assessment is unique to this model and leads to the identification of adaptation problems or nursing diagnoses.

Roy and colleagues have developed a typology of nursing diagnoses from the perspective of the Roy Adaptation Model (Roy, 1984; Roy & Roberts, 1981). In this typology, commonly recurring problems have been related to the basic needs of the four adaptive modes (Andrews & Roy, 1991).

Intervention is based specifically on the model, but there is a need to develop an organization of categories of nursing interventions (Roy & Roberts, 1981). Nurses provide interventions that alter, increase, decrease, remove, or maintain stimuli (Roy & Andrews, 1999). The nursing judgment model outlined by McDonald and Harms (1966) is recommended by Roy to guide selection of the best intervention for modifying a particular stimulus. According to this model, a number of alternative interventions are generated that may be appropriate for modifying the stimulus. Each possible intervention is judged for the expected consequences of modifying a stimulus, the probability that a consequence will occur (high, moderate, or low), and the value of the change (desirable or undesirable).

Senesac (2003) reviewed the literature for evidence that the Roy Adaptation Model is being implemented in nursing practice. She reported that the Roy Adaptation Model has been used to the greatest extent by individual nurses to understand, plan, and direct nursing practice in the care of individual patients. Although fewer examples of implementation of the adaptation model are found in institutional practice settings, such examples do exist. She concluded that if the model is to be implemented successfully as a practice philosophy, it should be reflected in the mission and vision statements of the institution, recruitment tools, assessment tools, nursing care plans, and other documents related to patient care.

The Roy Adaptation Model is useful in guiding nursing practice in institutional settings. It has been implemented in a neonatal intensive care unit, an acute surgical ward, a rehabilitation unit, two general hospital units, an orthopedic hospital, a neurosurgical unit, and a 145-bed hospital, among others (Roy & Andrews, 1999).

Weiland (2010) described use of the Roy Adaptation Model in the critical care setting by advanced practice nurses to incorporate spiritual care into nursing care of patients and families. Spiritual care is an important, but often overlooked, aspect of nursing care for patients in the critical care setting.

The Roy Adaptation Model has been applied to the nursing care of individual groups of patients. Examples of the wide range of applications of the Roy Adaptation Model are found in the literature. Villareal (2003) applied the Roy Adaptation Model to the care of young women who were contemplating smoking cessation. The author provides a comprehensive discussion of the use of Roy’s six-step nursing process to guide nursing care for women in their mid-twenties who smoked and were members of a closed support group. The researcher performed a two-level assessment. In the first level, stimuli were identified for each of the four adaptive modes. In the second level, the nurse made a judgment about the focal (nicotine addiction), contextual (belief that smoking is enjoyable, makes them feel good, relaxes them, brings them a sense of comfort, and is part of their routine), and residual stimuli (beliefs and attitudes about their body image and that smoking cessation causes weight gain). The nurse made the nursing diagnosis that for this group, a lack of motivation to quit smoking was related to dependency. The women in the support group and the nurse mutually established short-term goals to change behaviors, rather than the long-term goal of smoking cessation. The intervention focused on discussion of the effects of smoking on the body, reasons and beliefs about smoking and smoking cessation, stress management, nutrition, physical activity, and self-esteem. During the evaluation phase, it was determined that the women had moved from pre-contemplation to the contemplation phase of smoking cessation. The author concluded that the Roy Adaptation Model provided a useful framework for providing care to women who smoke.

Samarel, Tulman, and Fawcett (2002) examined the effects of two types of social support (telephone and group social support) and education on adaptation to early-stage breast cancer in a sample of 125 women. Women in the experimental group received both types of social support and education (n = 34); women in the first control group received only telephone support and education, and women in the second control group received only education. Mood disturbance and loneliness were reduced significantly for the experimental group and for the first control group but were not reduced for the second control group. No differences were observed among the groups in terms of cancer-related worry or well-being. This study provides an excellent example of how the Roy Adaptation Model can be used to guide the conceptualization, literature review, theory construction, and development of an intervention.

Zeigler, Smith, and Fawcett (2004) described the use of the Roy Adaptation Model to develop a community-based breast cancer support group, the Common Journey Breast Cancer Support Group. A qualitative study design was used to evaluate the program from both participant and facilitator perspectives. Responses from participants were categorized using the Roy Adaptation Model. Findings from this study showed that the program was effective in providing support for women with various stages of breast cancer.

Newman (1997a) applied the Roy Adaptation Model to caregivers of chronically ill family members. With a thorough review of the literature, Newman demonstrated how the Roy Adaptation Model was used to provide care for this population. Newman views the chronically ill family member as the focal stimulus. Contextual stimuli include the caregiver’s age, gender, and relationship to the chronically ill family member. The caregiver’s physical health status is a manifestation of the physiological adaptive mode. The caregiver’s emotional responses to caregiving (i.e., shock, fear, anger, guilt, increased anxiety) are effective or ineffective responses of the self-concept mode. Relationships with significant others and support indicate adaptive responses in the interdependence mode. Caregivers’ primary, secondary, and tertiary roles are strained by the addition of the caregiving role. Practice and research implications illuminate the applicability of the Roy Adaptation Model for providing care to caregivers of chronically ill family members.

The Roy Adaptation Model has been applied to adult patients with various medical conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder (Nayback, 2009), to women in menopause (Cunningham, 2002), and to the assessment of an elderly man undergoing a right, below-the-knee amputation. The Roy Adaptation Model has been used to evaluate the care of needs of adolescents with cancer (Ramini, Brown, & Buckner, 2008), asthma (Buckner, Simmons, Brakefield, et al., 2007), high-normal or hypertensive blood pressure readings (Starnes & Peters, 2004), and death and dying (Dobratz, 2011).

Kan (2009) used the Roy Adaptation Model to study perceptions of recovery following coronary artery bypass surgery for patients who had undergone this surgery for the first time. Findings revealed a positive relationship between perception of recovery and role function. Knowledge of adaptive responses following cardiac surgery has important implications for discharge planning and discharge teaching.

Education

The Roy Adaptation Model defines the distinct purpose of nursing for students, which is to promote the adaptation of persons in each of the adaptive modes in situations of health and illness. This model distinguishes nursing science from medical science by having the content of these areas taught in separate courses. She stresses collaboration but delineates separate goals for nurses and physicians. According to Roy (1971), it is the nurse’s goal to help the patient put his or her energy into getting well, whereas the medical student focuses on the patient’s position on the health-illness continuum with the goal of causing movement along the continuum. She views the model as a valuable tool for analyzing the distinctions between the two professions of nursing and medicine. Roy (1979) believes that curricula based on this model support students’ understanding of theory development as they learn about testing theories and experience theoretical insights. Roy (1971, 1979) noted early on that the model clarified objectives, identified content, and specified patterns for teaching and learning.

The Roy Adaptation Model has been used in the educational setting and has guided nursing education at Mount Saint Mary’s College Department of Nursing in Los Angeles since 1970. As early as 1987, more than 100,000 student nurses had been educated in nursing programs based on the Roy Adaptation Model in the United States and abroad. The Roy Adaptation Model provides educators with a systematic way of teaching students to assess and care for patients within the context of their lives rather than just as victims of illness.

Dobratz (2003) evaluated the learning outcomes of a nursing research course designed from the perspective of the Roy Adaptation Model and described in detail how to teach the theoretical content to students in a senior nursing research course. The evaluation tool was a Likert-type scale that contained seven statements. Students were asked to disagree, agree, or strongly agree with seven statements. Four open-ended questions were included to elicit information from students about the most helpful learning activity, the least helpful learning activity, methods used by the instructor that enhanced learning and grasp of research, and what the instructor could have done to increase learning. The researcher concluded that a research course based on the Roy Adaptation Model helped students put the pieces of the research puzzle together.

Research

If research is to affect practitioners’ behaviors, it must be directed toward testing and retesting theories derived from conceptual models for nursing practice. Roy (1984) has stated that theory development and the testing of developed theories are the highest priorities for nursing. The model continues to generate many testable hypotheses to be researched.

Roy’s theory has generated a number of general propositions. From these general propositions, specific hypotheses can be developed and tested. Hill and Roberts (1981) have demonstrated the development of testable hypotheses from the model, as has Roy. Data to validate or support the model are created by the testing of such hypotheses; the model continues to generate more of this type of research. The Roy Adaptation Model has been used extensively to guide knowledge development through nursing research (Frederickson, 2000).

Roy (1970) has identified a set of concepts that form a model from which the process of observation and classification of facts would lead to postulates. These postulates concern the occurrence of adaptation problems, coping mechanisms, and interventions based on laws derived from factors that make up the response potential of focal, contextual, and residual stimuli. Roy and colleagues have outlined a typology of adaptation problems or nursing diagnoses (Roy, 1973, 1975, 1976b). Research and testing continue in the areas of typology and categories of interventions that have been derived from the model. General propositions also have been developed and tested (Roy & McLeod, 1981).

Practice-based research

DiMattio and Tulman (2003) described changes in functional status and correlates of functional status of 61 women during the 6-week postoperative period following a coronary artery bypass graft. Functional status was measured at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after surgery, using the Inventory of Functional Status in the Elderly and the Sickness Impact Profile. Significant increases were found in all dimensions of functional status except personal at the three measurement points. The greatest increases in functional status occurred at between 2 and 4 weeks after surgery. However, none of the dimensions of functional status had returned to baseline values at the 6-week point. This information will help women who have undergone coronary artery bypass graft surgery to better understand the recovery period and to set more realistic goals.

Young-McCaughan and colleagues (2003) studied the effects of a structured aerobic exercise program on exercise tolerance, sleep patterns, and quality of life in patients with cancer from the perspective of the Roy Adaptation Model. Subjects exercised for 20 minutes, twice a week, for 12 weeks. Significant improvements in exercise tolerance, subjective sleep quality, and psychological and physiological quality of life were demonstrated.

Yeh (2002) tested the Roy Adaptation Model in a sample of 116 Taiwanese boys and girls with cancer (7 to 18 years of age at the time of diagnosis). Two Roy propositions were tested. The first proposition is that environmental stimuli (severity of illness, age, gender, understanding of illness, and communication with others) influence biopsychosocial responses (health-related quality of life [HRQOL]). The second proposition is that the four adaptive modes are interrelated. Using structural equation modeling, the researcher found that severity of illness provided an excellent fit with stage of illness, laboratory values (white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelets, absolute neutrophil count), and total number of hospitalizations. Although it is not altogether clear how the focal and contextual stimuli were defined, this study showed that environmental stimuli (severity of illness, age, gender, understanding of illness, and communication with others) influence the biopsychosocial adaptive responses of children to cancer. Finally, this study demonstrated the interrelatedness of the physiological (physical HRQOL), self-concept (disease and symptoms HRQOL), interdependence (social HRQOL), and role function (cognitive HRQOL) adaptive modes.

Woods and Isenberg (2001) provide an example of theory synthesis. In their study of intimate abuse and traumatic stress in battered women, they developed a middle-range theory by synthesizing the Roy Adaptation Model with the current literature reporting on intimate abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder. A predictive correlational model was used to examine adaptation as a mediator of intimate abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder. The focal stimulus of this study was the severity of intimate abuse, emotional abuse, and risk of homicide by an intimate partner. Adaptation was operationalized within the four adaptive modes and was tested as a mediator between intimate abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder. Direct relationships were reported between the focal stimulus and intimate abuse, and adaptation in each of the four modes mediated relationships between the focal stimulus and traumatic stress.

Chiou (2000) conducted a meta-analysis of the interrelationships among Roy’s four adaptive modes. Using well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, a literature search of the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature yielded eight research reports with diverse samples. One in-press report was included. Convenience samples for the nine studies included only adults, and some were elderly. The meta-analysis revealed small to medium correlations between each two mode set and a nonsignificant association between the interdependence and physiological modes. Zhan (2000) found support for Roy’s proposition about cognitive adaptive processes in relation to maintaining self-consistency. Using Roy’s Cognitive Adaptation Processing Scale (Roy & Zhan, 2001) to measure cognitive adaptation and the Self-Consistency Scale (Zhan & Shen, 1994), Zhan found that cognitive adaptation plays an important role in helping older adults maintain self-consistency in the face of hearing loss. Self-consistency was higher for hearing-impaired men than for hearing-impaired women, but it did not vary for age, educational level, race, marital status, or income.

Nuamah, Cooley, Fawcett, and McCorkle (1999) studied quality of life in 515 patients with cancer. These researchers clearly established theoretical linkages among the concepts of the Roy Adaptation Model, middle-range theory concepts, and empirical indicators. Focal and contextual stimuli were identified. Variables in each of the adaptive modes were operationalized. Using structural equation modeling, the researchers found that two of the environmental stimuli (adjuvant cancer treatment and severity of the disease) explained 59% of the variance in biopsychosocial indicators of the latent variable health-related quality of life. Their findings supported the proposition of the Roy Adaptation Model that environmental stimuli influence biopsychosocial responses.

Samarel and colleagues (1998, 1999) used the Roy Adaptation Model to study women’s perceptions of adaptation to breast cancer in a sample of 70 women who were participating in an experimental support and education group. The experimental group received coaching; the control group received no coaching. Using quantitative content analysis of structured telephone interviews, the researchers found that 51 of 70 women (72.9%) experienced a positive change toward their breast cancer over the study period, which was indicative of adaptation to the breast cancer. The researchers report qualitative indicators of adaptation for each of Roy’s four adaptive modes.

Modrcin-Talbott and colleagues studied self-esteem from the perspective of the Roy Adaptation Model in 140 well adolescents (Modrcin-Talbott, Pullen, Ehrenberger, et al., 1998) and 77 adolescents in an outpatient mental health setting (Modrcin-Talbott, Pullen, Zandstra, et al., 1998). Well adolescents were grouped in terms of early (12 to 14 years), middle (15 to 16 years), or late adolescence (17 to 19 years). Well adolescents were recruited conveniently from a large, southeastern church. Self-esteem in well adolescents did not differ by age group, gender, or whether or not they smoked tobacco. Well adolescents who exercised regularly did score higher on self-esteem. Significant negative relationships were found between self-esteem and depression, state anger, trait anger, anger-in, anger-out, anger control, and anger expression. In the second study, adolescents were sampled from participants of regularly scheduled group sessions as part of an outpatient psychiatric treatment program. Self-esteem significantly differed by age group, with older adolescents scoring lowest on self-esteem. Self-esteem did not differ by gender or whether or not they smoked tobacco. A significant negative relationship was observed between self-esteem and depression. Unlike their study in well adolescents, no statistically significant relationship was found between self-esteem and the dimensions of anger. Self-esteem was not significantly related to parental alcohol use in either group.

Modrcin-Talbott, Harrison, Groer, and Younger (2003) tested the effects of gentle human touch on the biobehavioral adaptation of preterm infants based on the Roy Adaptation Model. According to Roy, infants are born with two adaptive modes: the physiological and interdependence modes. Premature infants often are deprived of human touch, and an environment filled with machines, noxious stimuli, and invasive procedures surrounds them. These researchers found that gentle human touch (focal stimulus) promotes physiological adaptation for premature infants. Heart rate, oxygen saturation stability, increased quiet sleep, less active sleep and drowsiness, decreased motor activity, increased time not moving, and decreased behavioral distress cues were identified as effective responses in the physiological adaptive mode. This study supports Roy’s conceptualization of adaptation in infants.

Weiss, Fawcett, and Aber (2009) used the Roy Adaptation Model to study adaptation in postpartum women following caesarean delivery. Findings showed fewer adaptive responses in women with unplanned caesarean delivery. Cultural differences in adaptive responses were found among African-American and Hispanic women compared to Caucasian women. Implications for nursing practice include early assessment of adaptive responses and learning needs for patients who have had caesarean delivery to develop a discharge teaching plan to facilitate adaptive responses postdischarge.

The University of Montreal Research Team in Nursing Science (Ducharme, Ricard, Duquette, et al., 1998; Levesque, Ricard, Ducharme, et al., 1998) is studying adaptation to a variety of environmental stimuli. Four groups of individuals were included in their studies as follows: (1) informal family caregivers of a demented relative at home, (2) informal family caregivers of a psychiatrically ill relative at home, (3) nurses as professional caregivers in geriatric institutions, and (4) aged spouses in the community. Using linear structural relations (LISREL), perceived stress (focal stimulus), social support (contextual stimulus), and passive and avoidance coping (coping mechanism) were directly or indirectly linked to psychological distress. This finding supports Roy’s proposition that coping promotes adaptation.

DeSanto-Madeya (2009) studied adaptation in individuals with spinal cord injury and their family members using the Roy Adaptation Model. In this study, fifteen patient and family member dyads were included. Of the fifteen dyads, seven dyads were 1 year postinjury, and eight dyads were 3 years postinjury. Telephone interviews using the Adaptation to Spinal Cord Injury Interview Schedule (ASCIIS) were conducted. Findings showed that both individuals and families had moderate adaptation scores at both 1 year and 3 years. Study findings have important implications for nurses who must care for spinal cord injury patients in both acute and outpatient care settings.

Development of adaptation research instruments

The Roy Adaptation Model has provided the theoretical basis for the development of a number of research instruments. Newman (1997b) developed the Inventory of Functional Status–Caregiver of a Child in a Body Cast to measure the extent to which parental caregivers continue their usual activities while a child is in a body cast. Reliability testing indicates that the subscales for household, social, and community child care of the child in a body cast, child care of other children, and personal care (rather than the total score) are reliable measures of these constructs. Modrcin-McCarthy, McCue, and Walker (1997) used the Roy Adaptation Model to develop a clinical tool that may be used to identify actual and potential stressors of fragile premature infants and to implement care for them. This tool measures signs of stress, touch interventions, reduction of pain, environmental considerations, state, and stability (STRESS).

Development of middle-range theories of adaptation

Silva (1986) pointed out early on that merely using a conceptual framework to structure a research study is not theory testing. Many researchers have used Roy’s model but did not actually test propositions or hypotheses of her model. They have provided face validity of its usefulness as a framework to guide their studies. How theory derives from a conceptual framework must be made explicit; therefore, development and testing of middle-range theories derived from the Roy Adaptation Model are needed. Some research of this nature has been conducted with the model, but more is needed for further validation and development of new areas. The model does generate many testable hypotheses related to both practice and nursing theory. The success of a conceptual framework is evaluated, in part, by the number and quality of middle-range theories it generates. The Roy Adaptation Model has been the theoretical source of a number of middle-range theories (Roy, 2011a). The utility of those theories in practice sustains the life of the model.

Dunn (2004) reports the use of theoretical substruction to derive a middle-range theory of adaptation for chronic pain from the Roy Adaptation Model. In Dunn’s model of adaptation to chronic pain, pain intensity is specified as the focal stimulus. Contextual stimuli include age, race, and gender. Religious and nonreligious coping are functions of the cognator subsystem. Manifestations of adaptation to chronic pain are its effects on functional ability and psychological and spiritual well-being.

Frame, Kelly, and Bayley (2003) developed the Frame theory of adolescent empowerment by synthesizing the Roy Adaptation Model, Murrell-Armstrong’s empowerment matrix, and Harter’s developmental perspective. The theory of adolescent empowerment was tested using a quasi-experimental design in which children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were randomly assigned to a treatment or a control group. Ninety-two fifth and sixth grade students were assigned to the treatment or the control group. Children in the treatment group attended an eight-session, school nurse–led support group intervention (twice weekly for 4 weeks). The treatment was designed to teach the children about ADHD; the gifts of having ADHD, powerlessness versus empowerment; empowerment with one’s feelings, teachers, family, and classmates; and how to learn to relax. Children in the control group received no intervention. Using analysis of covariance, children in the treatment group reported significantly higher perceived social acceptance, perceived athletic competence, perceived physical appearance, and perceived global self-worth.

Jirovec, Jenkins, Isenberg, and Baiardi (1999) have proposed a middle-range urine control theory derived from the Roy Adaptation Model, intended to explicate the phenomenon of urine control and to decrease urinary incontinence. According to the theory of urine control, the focal stimulus for urine control is bladder distention. Contextual stimuli include accessible facilities and mobility skills. A residual stimulus is the intense socialization about bladder and sanitary habits that begin in childhood. This theory takes into account physiological coping mechanisms, regulator (spinal reflex mediated by S2 to S4, and coordinated detrusor muscle contraction and sphincter relaxation) and cognator (perception, learning judgment, and awareness of urgency or dribbling). Adaptive responses to prevent urinary incontinence are described for the four adaptive modes. Effective adaptation is defined as continence, and ineffective adaptation is defined as incontinence. The authors provide limited support for the theory of urine control through case studies. The theory of urine control illuminates the complexity, multidimensionality, and holistic nature of adaptation.

Researchers at the University of Montreal have proposed a middle-range theory of adaptation to caregiving that is based on the Roy Adaptation Model. This middle-range theory has been tested in a number of published studies of informal caregivers of demented relatives at home, informal caregivers of psychiatrically ill relatives at home, professional caregivers of elderly institutionalized patients, and aged spouses in the community. Perceived stress is conceptualized as the focal stimulus. Contextual stimuli include gender, conflicts, and social support. Coping mechanisms include active, passive, and avoidant coping strategies. In this middle-range theory, the adaptive (nonadaptive) response (psychological distress) is manifested in the self-concept mode. LISREL analyses have provided support for many of the propositions of this middle-range theory of adaptation to caregiving and for the Roy Adaptation Model (Ducharme, Ricard, Duquette, et al., 1998; Levesque, Ricard, Ducharme, et al., 1998).

Tsai, Tak, Moore, and Palencia (2003) derived a middle-range theory of pain from the Roy Adaptation Model. In the theory of chronic pain, chronic pain is the focal stimulus, disability and social support are contextual stimuli, and age and gender are residual stimuli. Perceived daily stress is a coping process. Depression is an outcome variable manifested in all four adaptive modes. Path analysis provided partial support for the theory of chronic pain. Greater chronic pain and disability were associated with more daily stress, and greater social support was associated with less daily stress. These three variables accounted for 35% of the variance in daily stress. Greater daily stress explained 35% of the variance in depression.

Other middle-range theories derived from the Roy Adaptation Model have been proposed, but research reports testing these theories were not found at the time of this literature review. Tsai (2003) has proposed a middle-range theory of caregiver stress. Whittemore and Roy (2002) developed a middle-range theory of adapting to diabetes mellitus using theory synthesis. Based on an analysis of Pollock’s (1993) middle-range theory of chronic illness and a thorough review of the literature, reconceptualization of the chronic illness model and the addition of concepts such as self-management, integration, and health-within-illness more specifically extend the Roy Adaptation Model to adapting to diabetes mellitus. Pollock’s (1993) research on adaptation to chronic illness theory included patients with insulin-dependent diabetes, multiple sclerosis, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Further development

The Roy Adaptation Model is an approach to nursing that has made and continues to make a significant contribution to the body of nursing knowledge; however, areas remain for future development as health care progresses. A thoroughly defined typology of nursing diagnoses and an organization of categories of interventions would facilitate its use in nursing practice. Scientists who do research from the perspective of the Roy Adaptation Model continue to note overlap in the psychosocial categories of self-concept, role function, and interdependence. Roy recently has redefined health, deemphasizing the concept of a health-illness continuum and conceptualizing health as integration and wholeness of the person. This approach more clearly incorporates the adaptive mechanisms of the comatose patient in response to tactile and verbal stimuli. However, because health was not conceptualized in this manner in the earlier work, this opens up a new area for research. Based on her integrative review of the literature, Frederickson (2000) concluded that there is good empirical support for Roy’s conceptualization of person and health. She made the following recommendations for future research. First, there is a need to design studies to test propositions related to environment and nursing. Second, interventions based on previously supported concepts and propositions have been tested, while others remain for testing to document evidence.

Critique

Clarity

The metaparadigm concepts of the Roy Adaptation Model (person, environment, nursing, and health) are clearly defined and consistent. Roy clearly defines the four adaptive modes (physiological, self-concept, interdependence, and role function). A challenge of the model that was identified is Roy’s espousal of a holistic view of the person and environment, while the model views adaptation as occurring in four adaptive modes, and person and environment are conceptualized as two separate entities, with one affecting the other (Malinski, 2000). An answer to this challenge is that Roy’s adaptation model is holistic, since change in the internal or external environment (stimulus) leads to response (adapts) as a whole. In fact, Roy’s perspective is consistent with other holistic theories, such as psychoneuroimmunology and psychoneuroendocrinology. As one example, psychoneuroimmunology is a theory that proposes a bidirectional relationship between the mind and the immune system. Roy’s model is broader than psychoneuroimmunology and provides a theoretical foundation for research about, and nursing care of, the person as a whole.

In more recent writings, Roy has acknowledged the holistic nature of persons who live in a universe that is “progressing in structure, organization, and complexity. Rather than a system acting to maintain itself, the emphasis shifts to the purposefulness of human existence in a universe that is creative” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 35).

Roy has written that other disciplines focus on an aspect of the person, and that nursing views the person as a whole (Roy & Andrews, 1999). “Based on the philosophic assumptions of the nursing model, persons are seen as coextensive with their physical and social environments. The nurse takes a values-based stance, focusing on awareness, enlightenment and faith” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 539). Roy contends that persons have mutual, integral, and simultaneous relationships with the universe and God, and that as humans they “use their creative abilities of awareness, enlightenment, and faith in the processes of deriving, sustaining, and transforming the universe” (Roy & Andrews, 1999, p. 35). Using these creative abilities, persons (sick or well) are active participants in their care and are able to achieve a higher level of adaptation (health).

Mastal and Hammond (1980) discussed difficulties with Roy’s model in classifying certain behaviors because concept definitions overlapped. The problem dealt with theory conceptualization and the need for mutually exclusive categories to classify human behavior. Conceptualizing a person’s position on the health-illness continuum is no longer a problem because Roy redefined health as personal integration. Other researchers have referred to difficulty in classifying behavior exclusively in one adaptive mode (Bradley & Williams, 1990; Limandri, 1986; Nyqvist & Sjoden, 1993; Silva, 1987). However, this observation supports Roy’s proposition that behavior in one adaptive mode affects and is affected by the other modes.

Simplicity

The Roy model includes the concepts of nursing, person, health-illness, environment, adaptation, and nursing activities. It also includes two subconcepts (regulator and cognator) and four modes (physiological, self-concept, role function, and interdependence). This model has several major concepts and subconcepts, so the relational statements are complex until the model is learned.

Generality

The Roy Adaptation Model’s broad scope is an advantage because it may be used for theory building and for deriving middle-range theories for testing in studies of smaller ranges of phenomena (Reynolds, 1971). Roy’s model (Roy & Corliss, 1993) is generalizable to all settings in nursing practice but is limited in scope, as it primarily addresses the person-environment adaptation of the patient, and information about the nurse is implied.

Accessibility

Roy’s broad concepts stem from theory in physiological psychology, psychology, sociology, and nursing; empirical data indicate that this general theory base has substance. Roy’s model offers direction for researchers who want to incorporate physiological phenomena in their studies. Roy (1980) studied and analyzed 500 samples of patient behaviors collected by nursing students. From this analysis, Roy proposed her four adaptive modes in humans.

Roy (Roy & McLeod, 1981; Roy & Roberts, 1981) has identified many propositions in relation to the regulator and cognator mechanisms and the self-concept, role function, and interdependence modes. These propositions have received varying degrees of support from general theory and empirical data. Most of the propositions are relational statements and can be tested (Tiedeman, 1983). Over the years, many testable hypotheses have been derived from the model (Hill & Roberts, 1981).

In spite of the progress made over the last 25 years, the greatest need to increase the empirical precision of the Roy Adaptation Model is for researchers to develop middle-range theory based on the Roy Adaptation Model with empirical referents specifically designed to measure concepts proposed in the derived theory. Roy has explicated a significant number of propositions, theorems, and axioms to serve in the development of middle-range theory. The holistic nature of the model serves nurse researchers worldwide who are interested in the complex nature of physiological and psychosocial adaptive processes (Roy, 2011a; 2011b).

Importance

The Roy Adaptation Model has a clearly defined nursing process and is useful in guiding clinical practice. The utility of the model has been demonstrated globally by nurses. This model provides direction for quality nursing care that addresses the holistic needs of the patient. The model is also capable of generating new information through the testing of hypotheses that have been derived from it (Roy, 2011a; Roy & Corliss, 1993; Smith, Garvis, & Martinson, 1983).

Summary

The Roy Adaptation Model has greatly influenced the profession of nursing. It is one of the most frequently used models to guide nursing research, education, and practice. The model is taught as part of the curriculum of most baccalaureate, master’s, and doctoral programs of nursing. The influence of the Roy Adaptation Model on nursing research is evidenced by the vast number of qualitative and quantitative research studies it has guided. The Roy Adaptation Model has inspired the development of many middle-range nursing theories and of adaptation instruments. Sister Callista Roy continues to refine the adaptation model for nursing research, education, and practice.

According to Roy, persons are holistic adaptive systems and the focus of nursing. The internal and external environment consists of all phenomena that surround the human adaptive system and affect their development and behavior. Persons are in constant interaction with the environment and exchange information, matter, and energy; that is, persons affect and are affected by the environment. The environment is the source of stimuli that either threaten or promote a person’s existence. For survival, the human adaptive system must respond positively to environmental stimuli. Humans make effective or ineffective adaptive responses to environmental stimuli. Adaptation promotes survival, growth, reproduction, mastery, and transformation of persons and the environment. Roy defines health as a state of becoming an integrated and whole human being.

Three types of environmental stimuli are described in the Roy Adaptation Model. The focal stimulus is that which most immediately confronts the individual and demands the most attention and adaptive energy. Contextual stimuli are all other stimuli present in the situation that contribute positively or negatively to the strength of the focal stimulus. Residual stimuli affect the focal stimulus, but their effects are not readily known. These three types of stimuli together form the adaptation level. A person’s adaptation level may be integrated, compensatory, or compromised.

Coping mechanisms refer to innate or acquired processes that a person uses to deal with environmental stimuli. Coping mechanisms may be categorized broadly as the regulator or cognator subsystem. The regulator subsystem responds automatically through innate neural, chemical, and endocrine coping processes. The cognator subsystem responds through innate and acquired cognitive-emotive processes that include perceptual and information processing, learning, judgment, and emotion.

Behaviors that manifest adaptation can be observed in four adaptive modes. The physiological mode refers to the person’s physical responses to the environment, and the underlying need is physiological integrity. The self-concept mode refers to a person’s thoughts, beliefs, or feelings about himself or herself at any given time. The basic need of the self-concept mode is psychic or spiritual integrity. The self-concept is a composite belief about self that is formed from internal perceptions and the perceptions of others. The self-concept mode is composed of the physical self (body sensation and body image) and the personal self (self-consistency, self-ideal, and the moral-ethical-spiritual self). The role function mode refers to the primary, secondary, and tertiary roles a person performs in society.

The basic need of the role function adaptive mode is social integrity or for one to know how to behave and what is expected of him or her in society. The interdependence adaptive mode refers to relationships among people. The basic need of the interdependence adaptive mode is social integrity or to give and receive love, respect, and value from significant others and social support systems (Table 17–1).

TABLE 17-1

Overview of the Adaptive Modes

| Subsystem | Adaptive Mode | Coping Need |

| Regulator Neural Chemical Endocrine | Physiological The physiological adaptive mode refers to the way a person, as a physical being, responds to and interacts with the internal and external environment Basic need: Physiological integrity | Oxygenation: To maintain appropriate oxygenation through ventilation, gas exchange, and gas transport Nutrition: To maintain function, to promote growth, and to replace tissue through ingestion and assimilation of food Elimination: To excrete metabolic wastes primarily through the intestines and kidney Activity and rest: To maintain balance between physical activity and rest Protection: To defend the body against infection, trauma, and temperature changes primarily by way of integumentary structures and innate and acquired immunity Senses: To enable persons to interact with their environment by sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell Fluid and electrolyte and acid-base balance: To maintain homeostatic fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance to promote cellular, extracellular, and systemic function Neurological function: To coordinate and control body movements, consciousness, and cognitive-emotional processes Endocrine function: To integrate and coordinate body functions |

| Cognator | Self-Concept | Physical Self |

| The self-concept adaptive mode refers to the psychological and spiritual characteristics of a person. The self-concept consists of the composite of a person’s feelings about himself or herself at any given time. The self-concept is formed from internal perceptions and the perceptions of others’ reactions. The self-concept has two major dimensions: the physical self and the personal self. Basic need: Psychic and spiritual integrityInterdependence Basic need: Relational integrity or security in nurturing relationships Role Function Basic need: Social integrity | Body sensation: To maintain a positive feeling about one’s physical being (i.e., physical functioning, sexuality, or health) Body image: To maintain a positive view of one’s physical body and physical appearance Personal Self Self-consistency: To maintain consistent self-organization and to avoid dysequilibrium Self-ideal or self-expectancy: To maintain a positive or hopeful view of what one is, what one expects to be, and what one hopes to do Moral-spiritual-ethical self: To maintain a positive evaluation of who one is To maintain close, nurturing relationships with people who are willing to give and receive love, respect, and value To know who one is and what society’s expectations are so that one can act appropriately within society |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree