Drugs Used for Anxiety Disorders

Objectives

1 Define the key words that are associated with anxiety states.

2 Describe the essential components of a baseline assessment of a patient’s mental status.

3 Cite the drug therapy used to treat anxiety disorders and any adverse effects that may result.

Key Terms

anxiety ( ) (p. 241)

) (p. 241)

generalized anxiety disorder (

) (p. 241)

) (p. 241)

panic disorder ( ) (p. 241)

) (p. 241)

phobias ( ) (p. 242)

) (p. 242)

obsessive-compulsive disorder ( ) (p. 242)

) (p. 242)

compulsion ( ) (p. 242)

) (p. 242)

anxiolytics ( ) (p. 242)

) (p. 242)

tranquilizers ( ) (p. 242)

) (p. 242)

Anxiety Disorders

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Anxiety is a normal human emotion that is similar to fear. It is an unpleasant feeling of apprehension or nervousness, and it is caused by the perception of potential or actual danger that threatens a person’s security. Mild anxiety is a state of heightened awareness of one’s surroundings, and it is seen in response to day-to-day circumstances. This type of anxiety can be beneficial as a motivator for the individual to take action in a reasonable and adaptive manner. It is sometimes said that people find the inner strength to meet their challenges or “rise to the occasion.”

Patients are considered to have anxiety disorders when their responses to stressful situations are abnormal or irrational and when they impair normal daily functioning. The National Institute of Mental Health identifies anxiety disorders as the most commonly encountered mental disorders in clinical practice; 16% of the general population will experience anxiety disorders during their lifetimes. Anxiety disorders usually begin before the age of 30 years, and they are more common among women than men. Patients who develop anxiety disorders often have more than one. They may also have major depression or develop substance abuse problems. The most common disorders are generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, simple phobia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Generalized anxiety disorder is described as excessive and unrealistic worry about two or more life circumstances (e.g., finances, illness, misfortune) for 6 months or more. Symptoms are both psychological (e.g., tension, fear, difficulty concentrating, apprehension) and physical (e.g., tachycardia, palpitations, tremor, sweating, gastrointestinal upset). The disease has a gradual onset, usually among individuals in the 20- to 30-year-old age-group, and it is equally common among both men and women. This illness usually follows a chronic fluctuating course of exacerbations and remissions that are triggered by stressful events in the person’s life. Patients with generalized anxiety disorder often develop other psychiatric disorders (e.g., panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, major depression) at some time during their lives.

Panic disorder is recognized as a separate entity and not as a more severe form of chronic generalized anxiety disorder. The average age of onset is during the late 20s; the disorder is often relapsing, and it may require lifetime treatment. Panic disorder is estimated to affect 1% to 2% of Americans at some time during their lives. Women are affected two to three times more frequently than men. Genetic factors appear to play a significant role in the disease; 15% to 20% of patients will have a close relative with a similar illness. Panic disorder begins as a series of acute or unprovoked anxiety (panic) attacks, which involve an intense, terrifying fear. The attacks do not occur as a result of exposure to anxiety-causing situations, as phobias do. Initially, the panic attacks are spontaneous, but later during the course of the illness they may be associated with certain actions (e.g., driving a car, being in a crowded place). Symptoms include dyspnea, dizziness, palpitations, trembling, choking, sweating, numbness, and chest pain. There are usually feelings of impending doom or a fear of losing control. Patients with panic disorder often develop other psychiatric disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder, personality disorders, substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, major depression) at some time during their lives.

Phobias are irrational fears of specific objects, activities, or situations. Unlike other anxiety disorders, the object or activity that creates the feeling of fear is recognized by the patient, who also realizes that the fear is unreasonable. The fear persists, however, and the patient seeks to avoid the situation. Social phobia is described as a fear of certain social situations in which the person is exposed to scrutiny by others and fears doing something embarrassing. A social phobia involving public speaking is fairly common, and the activity is usually avoided. If the public speaking is unavoidable, it is done with intense anxiety. Social phobias are rarely incapacitating, but they do cause some interference with social or occupational functioning. A simple phobia is an irrational fear of a specific object or situation, such as heights (acrophobia), closed spaces (claustrophobia), air travel, or driving. Phobias that involve animals such as spiders, snakes, and mice are particularly common. If the person with the phobia is exposed to the object, there is an immediate feeling of panic, sweating, and tachycardia. People are aware of their phobias, and they simply avoid the feared objects.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder is the most disabling of the anxiety disorders, although it is responsive to treatment. The primary features of the illness are recurrent obsessions or compulsions that cause significant distress and interfere with normal occupational responsibilities, social activities, and relationships. The average age of onset of the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder is during late adolescence to the early 20s. The condition occurs with equal frequency in men and women, and there also appears to be a genetic component to the disease. An obsession is an unwanted thought, idea, image, or urge that the patient recognizes as time-consuming and senseless but that repeatedly intrudes into that patient’s consciousness, despite his or her attempts to ignore, prevent, or counteract it. Examples of obsessions are recurrent thoughts of dirt or germ contamination, a fear of losing things, a need to know or remember something, a need to count or check something, blasphemous thoughts, or concerns about something happening to the self or others. An obsession produces a tremendous sense of anxiety in the affected person. A compulsion is a repetitive, intentional, purposeful behavior that must be performed to decrease the anxiety associated with an obsession. The act is done to prevent a vague dreaded event, but the person does not derive pleasure from the act. Common compulsions deal with cleanliness, grooming, and counting. When patients are prevented from performing a compulsion, there is a sense of mounting anxiety. In some individuals, the compulsion can become the person’s lifetime activity.

Drug Therapy for Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is a component of many medical illnesses that involve the cardiovascular, pulmonary, digestive, and endocrine systems. It is also a primary symptom of many psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, mania, depression, dementia, and substance abuse. Therefore, the evaluation of the anxious patient requires a thorough history as well as physical and psychiatric examinations to determine whether the anxiety is a primary condition or secondary to another illness. Persistent irrational anxiety or episodic anxiety generally requires medical and psychiatric treatment. The treatment of anxiety disorders usually requires a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies. When it is decided to treat the anxiety in addition to the other medical or psychiatric diagnoses, antianxiety medications—also known as anxiolytics or tranquilizers—are prescribed. Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a complex condition that requires a highly individualized and integrated approach to treatment that includes pharmacologic, behavioral, and psychosocial components.

Actions

A great many medications have been used over the decades to treat anxiety. They range from the purely sedative effects of ethanol, bromides, chloral hydrate, and barbiturates to drugs with more specific antianxiety and less sedative activity, such as benzodiazepines, buspirone, meprobamate, hydroxyzine, and propranolol (a beta-adrenergic antagonist). More recently, tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., imipramine), serotonin agonists (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (extended-release venlafaxine), and serotonin antagonists (e.g., ondansetron) have been studied for the treatment of anxiety disorders. See the individual drug monographs later in this chapter for the mechanisms of action of these agents.

Uses

Generalized anxiety disorder is treated with psychotherapy and the short-term use of antianxiety agents. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved four classes of compounds or medications for treatment: (1) specific benzodiazepines; (2) paroxetine and escitalopram (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors); (3) extended-release venlafaxine; and (4) buspirone. To some extent, the beta-adrenergic blocking agents (see Chapter 13) are also used. Barbiturates, meprobamate, and antihistamines such as hydroxyzine are infrequently prescribed. Panic disorders may be treated with a variety of agents in addition to behavioral therapy. Alprazolam and clonazepam (benzodiazepines) as well as sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of panic disorder. Other agents that show benefit are the tricyclic antidepressants desipramine and clomipramine as well as mirtazapine and nefazodone (see Chapter 17). Phobias are treated with the use of avoidance, behavior therapy, and benzodiazepines or beta-adrenergic blockers such as propranolol or atenolol. Obsessive-compulsive disorder is treated with behavioral and psychosocial therapy in addition to paroxetine, sertraline, fluoxetine, or fluvoxamine.

Nursing Implications for Antianxiety Therapy

Nursing Implications for Antianxiety Therapy

Assessment

History of Behavior.

Obtain a history of the precipitating factors that may have triggered or contributed to the individual’s current anxiety. Has the individual been using alcohol or drugs? Has the patient had a recent adverse event, such as a job or relationship loss, the death of a loved one, or a divorce? Has the individual witnessed or survived a traumatic event? Does the individual have any medical problems (e.g., hyperthyroidism) that could be related to these symptoms? Are there symptoms present that could be attributed to a panic attack, such as a feeling of choking, palpitations, sweating, chest pain or discomfort, nausea, abdominal distress, or fear of losing control, going crazy, or dying? Does the person have symptoms of obsessions or compulsions? Does the individual have a history of agoraphobia (i.e., situations in which he or she feels trapped or unable to escape)? Did the attack occur in response to a social or performance situation? Is the client also depressed? What specific fears does the individual have?

Take a detailed history of all medications that the individual is taking. Is there any use of central nervous system (CNS) stimulants (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines) or CNS depressants (e.g., alcohol, barbiturates)? Adverse effects of medications being taken may be aggravating the person’s anxiety level.

Ask for details regarding how long the individual has been exhibiting anxiety. Has the person been treated for anxiety previously? When did the symptoms start? Did they begin during intoxication or withdrawal from a substance?

Basic Mental Status.

Note the patient’s general appearance and appropriateness of attire. Is the individual clean and neat? Is the posture stooped, erect, or slumped? Is the person oriented to date, time, place, and person? Determine whether the patient is at risk for harming herself or himself or others. Is he or she able to participate in self-directed activities of daily living, including eating and providing the self-care that is required to sustain life? These areas are regularly assessed to determine whether acute hospitalization is indicated. Otherwise, the outpatient setting is the most common setting for the treatment of anxiety disorders.

What coping mechanisms has the individual been using to deal with the situation? Are these mechanisms adaptive or maladaptive? Identify the individual’s ability to understand new information, follow directions, and provide self-care.

Identify events that trigger anxiety in the individual. Discuss the patient’s behavior and thoughts, and foster an understanding of this with his or her family members. Involve the family and significant others in the discussion of the anxiety-producing events or circumstances, and explain how these individuals can help the patient to reduce anxiety or cope more adaptively with stressors. Identify support groups.

Mood and Affect.

Is the individual tearful, excessively excited, angry, hostile, or apathetic? Is the facial expression tense, fearful, sad, angry, or blank? Ask the person to describe his or her feelings. Is there worry about real-life problems? Are the person’s responses displayed as an intense fear, detachment, or absence of emotions? If the patient is a child, are there episodes of tantrums or clinging?

Patients who are experiencing altered thinking, behavior, or feelings require the careful evaluation of their verbal and nonverbal actions. Often, the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are displayed are inconsistent with the so-called “normal responses” of individuals in similar circumstances. Identify management techniques for handling anxiety-producing situations effectively.

Assess whether the mood being described is consistent with or appropriate for the circumstances being described. For example, is the person speaking of death while smiling?

Clarity of Thought.

Evaluate the coherency, relevancy, and organization of the patient’s thoughts. Ask specific questions about the individual’s ability to make judgments and decisions. Is there any memory impairment? Identify areas in which the patient is capable of having input into setting goals and making decisions. (This will help the patient to overcome a sense of powerlessness over certain life situations.) When the patient is unable to make decisions, set goals to involve the patient to the degree of his or her capability, because abilities change with treatment.

Psychomotor Functions.

Ask specific questions regarding the activity level that the patient has maintained. Is the person able to work or go to school? Is the person able to fulfill responsibilities at work, socially, or within the family? How have the person’s normal responses to daily activities been altered? Is the individual irritable, angry, easily startled, or hypervigilant? Observe the patient for gestures, gait, hand tremors, voice quivering, and actions such as pacing or the inability to sit still.

Obsessions or Compulsions.

Does the individual experience persistent thoughts, images, or ideas that are inappropriate and cause increased anxiety? Are there repetitive physical or mental behaviors, such as handwashing, needing to arrange things in perfect symmetrical order, praying, or silently repeating words? If obsessions or compulsions are present, how often do these occur? Do the obsessions or compulsions impair the person’s social or occupational functioning?

Sleep Pattern.

What is the person’s normal sleep pattern, and how has it varied since the onset of the symptoms? Ask specifically whether insomnia is present. Ask the individual to describe the amount and quality of the sleep. What is the degree of fatigue that is present? Is the individual having recurrent stressful dreams (e.g., after a traumatic event)? Is there difficulty falling or staying asleep?

Dietary History.

Ask questions about the individual’s appetite, and note weight gains or losses not associated with intentional dieting.

Implementation

• Deal with problems as they occur; practice reality orientation.

• Identify signs of escalating anxiety; decrease the escalation of anxiety.

• Establish a trusting relationship with the patient by providing support and reassurance.

Allow the patient to make decisions of which he or she is capable; make decisions when the client is not capable; and provide a reward for progress when decisions are initiated appropriately. Involve the patient in self-care activities. During periods of severe anxiety or during escalating anxiety, the individual may be unable to have insight or to make decisions appropriately.

Encourage the individual to develop coping skills with the use of various techniques, such as rehearsing or role-playing responses to threatening stressors. Have the individual practice problem solving, and discuss the possible consequences of the solutions that are offered by the patient.

Assist individuals with nonpharmacologic measures, such as music therapy, relaxation techniques, or massage therapy.

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Patient Education and Health Promotion

Orient the individual to the unit and the rules of the unit. Explain the process of privileges and how they are obtained or lost. (The extent of the orientation and explanations given will depend on the individual’s orientation to date, time, place, and abilities.)

Explain activity groups and resources that are available within the community. A variety of group process activities (e.g., social skills group, self-esteem groups, work-related groups, physical exercise groups) exist in particular therapeutic settings. Meditation, biofeedback, and relaxation therapy may also be beneficial.

Involve the patient and his or her family in goal setting, and integrate them into the available group processes to develop positive experiences for the individual to enhance his or her coping skills.

Patient education should be individualized and based on assessment data to provide the individual with a structured environment in which to grow and enhance self-esteem. Initially, the individual may not be capable of understanding lengthy explanations; therefore, the approaches used should be based on the patient’s capabilities.

Explore the coping mechanisms that the person uses in response to stressors, and identify methods of channeling these toward positive realistic goals as an alternative to the use of medication.

Fostering Health Maintenance.

Throughout the course of treatment, discuss medication information and how the medication will benefit the patient. Stress the importance of the nonpharmacologic interventions and the long-term effects that compliance with the treatment regimen can provide. Additional health teaching and nursing interventions for adverse effects are described in the drug monographs later in this chapter. Seek cooperation and understanding regarding the following points so that medication compliance is increased: the name of the medication; its dosage, route, and times of administration; and its adverse effects. Instruct the patient not to suddenly discontinue prescribed medications after having been on long-term therapy. Withdrawal should be undertaken with instructions from a health care provider, and it usually requires 4 weeks of gradual reduction in dosage and widen the intervals of administration.

Written Record.

Enlist the patient’s help with developing and maintaining a written record of monitoring parameters (see the Patient Self-Assessment Form for Antianxiety Medication on the Evolve ![]() Web site). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track patient response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form, and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions that have been prescribed.

Web site). Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track patient response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form, and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions that have been prescribed.

Drug Class: Benzodiazepines

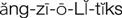

Benzodiazepines are most commonly used because they are more consistently effective, they are less likely to interact with other drugs, they are less likely to cause overdose, and they have less potential for abuse than barbiturates and other antianxiety agents. They account for perhaps 75% of the 100 million prescriptions that are written annually for anxiety. Six benzodiazepine derivatives are used as antianxiety agents (Table 16-1).

![]() Table 16-1

Table 16-1

Benzodiazepines Used to Treat Anxiety

| Generic Name | Brand Name | Availability | Initial Dosage (Given by Mouth) | Maximum Daily Dosage (mg) |

| alprazolam | Xanax, Apo-Alpraz | Tablets: 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 mg Tablets, orally disintegrating: 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 mg Solution: 1 mg/mL | 0.25-0.5 mg three times daily | 10 |

| Xanax XR | Tablets, extended release, 24 hour: 0.5, 1, 2, 3 mg | 0.5-1 mg daily | 6 | |

| chlordiazepoxide | Librium | Capsules: 5, 10, 25 mg | 5-10 mg three or four times daily | 300 |

| clorazepate | Tranxene T, Novo-Clopate | Tablets: 3.75, 7.5, 15 mg | 10 mg once to three times daily | 60 |

| diazepam | Valium, Apo-Diazepam | Tablets: 2, 5, 10 mg Liquid: 5 mg/5 mL Concentrate: 5 mg/mL Injection: 5 mg/mL in 2-mL prefilled syringe Rectal gel: 2.5, 10, 20 mg/ rectal delivery system | 2-10 mg two to four times daily | — |

| lorazepam | Ativan, Nu-Loraz | Tablets: 0.5, 1, 2 mg Liquid: 2 mg/mL Injection: 2, 4 mg/mL in 1-, 10-mL vials) | 2-3 mg two or three times daily | 10 |

| oxazepam | Apo-Oxazepam | Capsules: 10, 15, 30 mg | 10-15 mg three or four times daily | 120 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree