Child and Adolescent Health

Susan Rumsey Givens and Mary Brecht Carpenter

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Identify major indicators of child and adolescent health status.

2. Describe how socioeconomic circumstances influence child and adolescent health.

3. Discuss the individual and societal costs of poor child health status.

4. Discuss public programs and prevention strategies targeted to children’s health.

Key terms

adolescent pregnancy

child maltreatment

childhood immunization

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

cultural competence

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT)

fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD)

infant mortality

lead poisoning

Medicaid

preconceptional counseling

prenatal care

preterm birth

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

A nation’s destiny lies with the health, education, and well-being of its children. The United States has made tremendous progress over the past century toward improving children’s lives. Improvements in public health measures—such as sanitation, infectious disease control, environmental regulation, health screening, and education—and remarkable strides in medical care have all contributed to the good health status that most children enjoy. However, these improvements have not equally benefited children of all races and ethnic groups, children at all income levels, or children in all geographic areas of the country. For example, significant disparities persist in the health status of white children versus children of color. Children living in suburban areas and most outer urban areas experience superior access to health care services compared with children living in rural areas and inner cities, especially if they are poor.

Although most of the nation’s children are healthy and succeed in school, many are not enjoying optimal health and well-being and are not reaching their full potential as contributing members of society. Despite improvements, the mortality and morbidity rates for U.S. children in all age groups are unacceptably high. Consider:

• More than 28,000 infants die every year before reaching their first birthday.

• Eighteen percent of children aged 0 to 18 years live in poverty.

• More than 140,000 girls aged 15 to 17 years give birth each year.

• Violence is the second leading cause of death among adolescents (National Center for Health Statistics, 2009).

The health of a child has long-term implications. The health habits adopted by children and youth will profoundly influence their potential to lead healthy, productive lives. The physical and emotional health experienced by a child plays a pivotal role in his or her overall development and the well-being of the entire family. Children who go to school sick or hungry, who cannot see the chalkboard or hear the teacher, who have learning disabilities, who are troubled by abusive parents or disruptive living circumstances, or who fear for their safety at home or in school often do not perform on the level of their counterparts who are healthy, well nourished, well cared for at home, and safe and secure in their world. From fetal life onward, the health and well-being of individuals has a substantial impact on their futures.

In 2007, there were about 73.9 million children in the United States under age 18 years, forming about 25% of the country’s population. The number of children is expected to increase to 80 million by the year 2020, but the proportion of children as compared with adults has been decreasing since the mid-1960’s baby boom (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2008). The demographic composition of the nation is important to planners and policy makers because it influences how resources will be allocated. For example, a growing child population necessitates more resources for schools, child care, and health care.

The ethnic and racial composition of the United States’ child and adolescent population is also changing. The percentage of children living in the United States with at least one foreign-born parent rose from 15% in 1994 to 22% in 2007. About 20% of school-age children speak a language other than English at home.

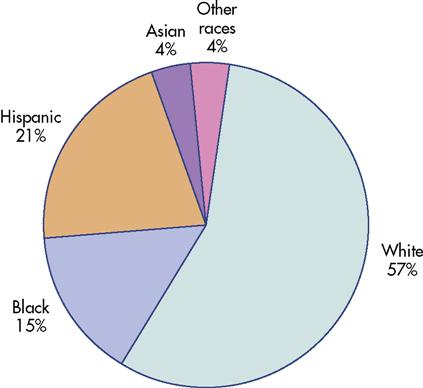

In 2007, 57% of children living in the United States were white, non-Hispanic; 21% were Hispanic; 15% were black; 4% were Asian; and 4% were of all other races (Figure 16-1). The percentage of children who are Hispanic has increased faster than that of any other racial or ethnic group, growing from 9% of the child population in 1980 to 21% in 2007. By 2020, it is projected that nearly one in four children in the United States will be of Hispanic origin (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2008).

Children are a dependent population and rely primarily on parents or other adults to protect and promote their health and well-being. Community health nurses can learn more about this important population group and the positive and negative factors that influence their health. Nurses can use this information to help improve the chances that children will grow up to be healthy, both physically and emotionally.

This chapter focuses on the health status of children and adolescents and the medical, socioeconomic, environmental, educational, safety, and public health factors that community health nurses must address to improve child and adolescent health. This chapter also discusses indicators of child and adolescent health status, the individual and societal costs of poor child health, public programs targeted to children’s health, and strategies to improve child and adolescent health at the individual, family, and community levels.

Issues of pregnancy and infancy

The health of the mother before, during, and after pregnancy has a direct impact on the health of her children. Predictors of healthy child development include genetic endowment, maternal health, environmental stresses, and health behaviors throughout her life. The conditions that surround a child’s fetal development and early years shape his or her life. Protection and promotion of maternal and child health can help ensure a healthy future for the child.

The first year of life is the most hazardous until the age of 65 years. Therefore, it is particularly important for women to be as healthy as possible before becoming pregnant, to receive prenatal care and adopt healthy lifestyle choices, and for infants to receive primary health care to maintain health and prevent or minimize serious, long-lasting health problems.

Infant Mortality

Infant mortality, the death of an infant during the first year of life, is a critical gauge of children’s health status. It is an important marker because it is related to several factors, including maternal health, medical care quality and access, socioeconomic conditions, and public health practices. Infant mortality reflects the health and welfare of an entire community and is used as a broad indicator of health care and health status. Box 16-1 lists some terms and definitions associated with infant health and mortality.

Surprisingly, the United States ranks a dismal twenty-ninth in infant mortality behind most other industrialized nations, including Japan, Sweden, Spain, Hong Kong, Italy, France, and Canada (Table 16-1). Fifty years ago, the United States ranked twelfth. The gap in infant mortality between the United States and other nations has occurred despite the United States’ comparatively high per capita spending on health care and technological advancements.

TABLE 16-1

International Comparisons of Infant Mortality Rates* for Selected Countries and Territories (2004)

| Rank | Country | Rate |

| 1 | Singapore | 2.0 |

| 2 | Hong Kong | 2.5 |

| 3 | Japan | 2.8 |

| 4 | Sweden | 3.1 |

| 5 | Norway | 3.2 |

| 6 | Finland | 3.3 |

| 7 | Spain | 3.5 |

| 8 | Czech Republic | 3.7 |

| 9 | France | 3.9 |

| 10 | Portugal | 4.0 |

| 11 | Germany | 4.1 |

| 11 | Greece | 4.1 |

| 11 | Italy | 4.1 |

| 11 | Netherlands | 4.1 |

| 15 | Switzerland | 4.2 |

| 16 | Belgium | 4.3 |

| 17 | Denmark | 4.4 |

| 18 | Austria | 4.5 |

| 18 | Israel | 4.5 |

| 20 | Australia | 4.7 |

| 21 | Ireland | 4.9 |

| 21 | Scotland | 4.9 |

| 23 | England/Wales | 5.0 |

| 24 | Canada | 5.3 |

| 25 | No. Ireland | 5.5 |

| 26 | New Zealand | 5.7 |

| 27 | Cuba | 5.8 |

| 28 | Hungary | 6.6 |

| 29 | Poland | 6.8 |

| 29 | Slovakia | 6.8 |

| 29 | United States | 6.8 |

| 32 | Puerto Rico | 8.1 |

| 33 | Chile | 8.4 |

| 34 | Costa Rica | 9.0 |

| 35 | Russian Federation | 11.5 |

| 36 | Bulgaria | 11.7 |

| 37 | Romania | 16.8 |

*Infant mortality rate represents infant deaths per 1000 live births.

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Health United States, 2007, 2007: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus07.pdf#025. Accessed May 13, 2009.

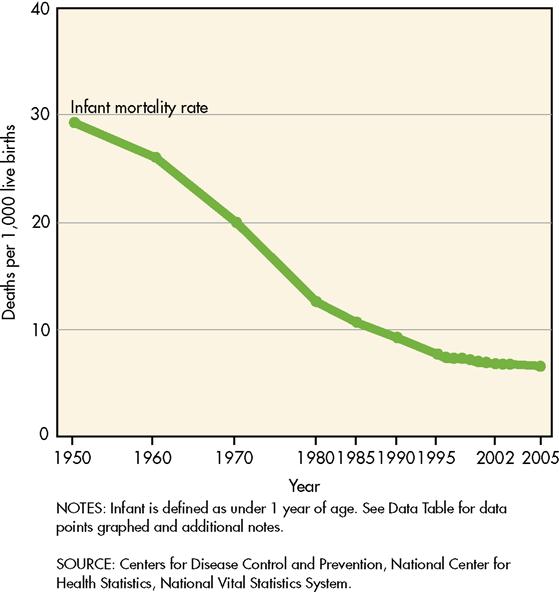

Despite a poor ranking among other nations in the world, in the past century, the infant mortality rate in the United States declined substantially (Figure 16-2). The 2006 infant death rate of 6.71 deaths per 1000 live births (MacDorman and Mathews, 2008) was the lowest infant mortality rate ever recorded in this country. The incidence of infant mortality has decreased largely because of public health measures and improved standard of living (e.g., improved sanitation, a clean milk supply, immunizations against deadly childhood diseases, the increased availability of nutritious food, and enhanced access to maternal health care). Technological advances in neonatal care, for example, the introduction of synthetic lung surfactant, have also contributed to reductions in infant mortality. However, declines in infant mortality have stagnated during the past decade.

The three leading causes of infant death in the United States are congenital malformations, deformities, and chromosomal abnormalities; disorders relating to short gestation and low birth weight; and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (Kung et al., 2007) (Box 16-2). Prematurity is a key risk factor for infant death. Socioeconomic factors also play an important role in infant mortality. Out-of-wedlock births pose greater risks for infant mortality, for example. In 2007, 40% of all babies were born to unmarried women, a rapidly increasing trend, particularly among Latino women (Martin et al., 2009). Infant mortality rates are also higher for children whose mothers receive late or no prenatal care, who are adolescents, who did not complete high school, who are unmarried, or who smoke during pregnancy.

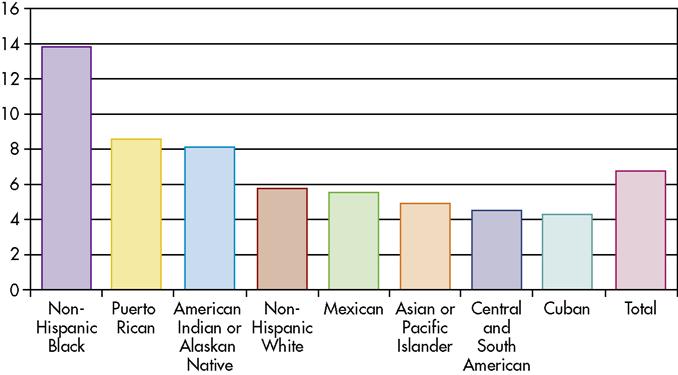

Troubling disparities in infant mortality persist between racial and ethnic populations. For example, black infants continue to die at more than twice the rate of white infants (Figure 16-3) (MacDorman and Mathews, 2008). Identifying and remedying the causes of higher infant mortality rates among certain population subgroups remains a vexing societal problem (Box 16-3).

Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight

Birth weight and length of gestation are the most important predictors of infant health. One reason infant mortality has declined so slowly in recent years is that the preterm rate (birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation) has risen so quickly over the past two decades. About 13% of babies in the United States are born prematurely. A portion of this increase is due to increases in multiple births, but prematurity among single births has also risen (Martin et al., 2007). The greatest rise in preterm births has occurred in babies who are born between 34 and 36 6/7 completed weeks of gestation (late preterm). Indeed, 70% of babies born prematurely are born late preterm (Hamilton et al., 2009).

Infants born preterm or at a low birth weight have a far greater risk of death and physical and mental disabilities such as blindness, deafness, cerebral palsy, learning disabilities, and mental retardation than infants born at term with normal weight. Even babies born late preterm carry a risk for developmental delay that is 36% higher than for babies born at term (Morse et al., 2009).

Prematurity and low birth weight overlap. About half of preterm infants are born at low birth weight, but only two thirds of low-birth-weight babies are born prematurely. Babies born at term but at low birth weight are considered “growth restricted.” Non-Hispanic black infants are disproportionately affected by preterm birth and low birth weight; indeed, they are nearly twice as likely as white infants to be born at low birth weight (Hamilton et al., 2009). Factors associated with preterm birth and low birth weight include the following:

• Maternal age of less than 17 years and more than 35 years

• Chronic health problems such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension

• Induced labor and elective cesarean birth

The development of advanced life-support technologies for small infants has significantly improved the survival rate of low-birth-weight babies. Success stories of tiny survivors are sensationalized in the news, but the long-term consequences of babies born even a few weeks early are not well publicized. Medical management of high-risk pregnancy and increasing numbers of labor inductions and elective cesarean births have helped to push the rate of late preterm birth upward. Consequences of late preterm birth can be long lasting and costly (Petrini et al., 2009; Morse et al., 2009; Bettegowda et al., 2008; Adams-Chapman, 2006; Institute of Medicine, Section IV, 2006). Because late preterm births account for the majority of preterm births, it is imperative that all possible measures are taken to decrease elective births before 39 weeks of gestation (Oshiro et al., 2009).

Preventing the occurrence of prematurity and low birth weight is a high priority for clinical and public health research and policy. Nurses can play important roles in preventing prematurity, through the provision of evidence-based primary care, research, screening, counseling, education, advocacy, referral, and implementation of interventions to reduce risk among target population groups.

Preconceptional Health

The good health of a woman before becoming pregnant is imperative to the health of her baby. Adapting healthy lifestyles and obtaining regular medical care before becoming pregnant can help to ensure a healthy pregnancy. Tiny developing fetal organ systems are highly vulnerable to the effects of maternal nutrition, drugs, alcohol, tobacco, chronic maternal diseases, environmental toxins, and other exposures. The fetus can suffer damage very early in pregnancy, even before a woman knows she is pregnant. This is important because approximately half of the pregnancies in the United States are unintended (Finer and Henshaw, 2006). Because of the likelihood that a woman may become pregnant, all women of childbearing age should adapt healthy lifestyles. Measures known to help ensure fetal health such as consuming 0.4 mg of the B vitamin folic acid every day, even before conception, will decrease the likelihood of defects of the brain and spine, known as neural tube defects (Wolff et al., 2009). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 50% to 70% of neural tube defects could be prevented if this recommendation were followed before and during early pregnancy, yet fewer than one third of women get the recommended amount of folic acid (CDC, 2008). For women planning to become pregnant, preconceptional counseling is a prevention strategy that helps to identify potential risks to a fetus before pregnancy. Preconception assessment encourages health and lifestyle modifications that can lead to healthier babies.

Prenatal Care

Obtaining early and regular prenatal care greatly enhances a woman’s chance of delivering a healthy, term baby. Prenatal care includes client education, risk identification, and monitoring and treatment of symptoms. It also includes referral to health, nutrition, and social service programs that can help a woman optimize her chances for a healthy pregnancy. In the past two decades, the Medicaid program was expanded to cover health care for increasing numbers of low-income pregnant women and infants. Still, fewer than 70% of women receive prenatal care beginning in the first trimester. Large disparities by race persist in the receipt of prenatal care. Non-Hispanic black and Hispanic women are more than twice as likely as non-Hispanic white women to receive late or no care (Martin et al., 2009). Examples of population groups that are less likely to receive early prenatal care include the following:

• Poor women who are under age 20 years and unmarried

• African-American, Hispanic, or Native-American women

• Women who live in isolated rural areas or medically underserved urban areas

• Women with less than 12 years of education

Timely and comprehensive prenatal care increases the identification of specific and treatable causes of infant morbidity and mortality, such as maternal anemia, diabetes, hypertension, urinary tract infections, sexually transmitted infections, and poor nutrition. Comprehensive prenatal care is particularly important for low-income women. It can help them obtain other services such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program, food stamps, smoking cessation, housing, child care, job training, substance abuse treatment, and domestic violence counseling.

Health education and counseling also are a part of comprehensive prenatal care and can provide women with the information they need to make lifestyle changes to help ensure a healthy pregnancy. Ideally, such counseling and treatment of chronic health conditions should begin before a woman becomes pregnant. Optimal health across her lifespan including treatment of chronic health conditions and the adaptation of a healthy lifestyle will have far more of an impact on healthy pregnancy than prenatal care alone.

Prenatal Substance Use

Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use are social factors that affect health. During pregnancy, substance use profoundly affects the neurological and physical development of the fetus. The use of these substances, in any combination, worsens infant health and development outcomes.

Smoking

The adverse health effects of tobacco use during pregnancy are well documented and include low birth weight, prematurity, stillbirth, intrauterine growth retardation, preterm premature rupture of membranes, placenta previa, placental abruption, neurodevelopmental impairment, and SIDS (CDC, 2007b). Cigarette smoke contains more than 2500 chemicals. The fetal effects of most of these chemicals are unknown. However, what is known is when a pregnant woman inhales cigarette smoke, the oxygen supply to her fetus is disrupted by nicotine and carbon monoxide. Nicotine crosses the placenta and becomes concentrated in fetal blood and amniotic fluid. Nicotine concentrations in the fetus of a smoking woman can be as much as 15% higher than maternal levels. Secondhand smoke exposure also is dangerous to the fetus and newborn. It is linked to SIDS, decreased respiratory functioning, and childhood asthma. Pregnant women who are exposed to secondhand smoke have 20% higher odds of giving birth to a low-birth-weight baby than women who are not exposed to secondhand smoke during pregnancy (Leonardi-Bee et al., 2008; CDC, 2007b).

About 13% of women reported smoking during the last three months of pregnancy. Teenagers and young women have the highest rates of maternal smoking (CDC, 2007b). The elimination of tobacco use among pregnant women would significantly reduce the percentage of low-birth-weight infants, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and infant mortality. Quitting is best. Merely reducing cigarette use during pregnancy may not be enough to benefit the fetus because women who cut back tend to inhale more deeply or take more puffs to get an equivalent amount of nicotine.

The need for widespread implementation of smoking cessation programs for women in the childbearing years is clear. Many smoking cessation programs have been developed and implemented by national, state, and local governments and organizations. Because pregnant women who have received even brief smoking cessation counseling are more likely to quit smoking, nurses should offer effective smoking cessation interventions to pregnant smokers at the first prenatal visit and throughout the pregnancy (Tong et al., 2008).

Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use

The use of alcohol and illicit drugs is a major risk factor for poor infant outcomes. No level of alcohol intake has been determined to be safe during pregnancy, but binge drinking (five or more drinks on the same occasion) is especially harmful to fetal development. Women who are pregnant or who may become pregnant should abstain from alcohol, yet an estimated 12% of pregnant women use alcohol during pregnancy and 2% of pregnant women report binge drinking (CDC, 2009a). Alcohol use during pregnancy can lead to spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, and a cluster of congenital defects, including the nervous system dysfunction called fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs). FASDs range from mild, subtle learning disabilities to severe learning disabilities. Children with FASD are at risk for psychiatric problems, criminal behavior, unemployment, and incomplete education. Many children with FASD also have physical abnormalities, growth deficiencies, and central nervous system disorders (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2007).

Like alcohol, illicit drugs can also cause permanent harm to an unborn baby. Nearly 4% of pregnant women report using drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy and other stimulants, and heroin. Risks to the baby include prematurity, low birth weight, birth defects, newborn withdrawal symptoms, and learning and behavioral problems. Further, illicit drug use often goes hand in hand with other maternal risks including tobacco and alcohol use, poor nutrition, and risk of sexually transmitted infections (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 2006).

Substance use is often a sign of more complex psychosocial problems such as depression, poverty, abuse, and violence. Because of serious potential risks to the developing fetus, women who are pregnant, or who could become pregnant, should be counseled to abstain from alcohol and the use of illicit drugs. For those women who already use alcohol and drugs, a comprehensive and long-lasting approach to treatment is required.

Childhood health issues

At all ages, appropriate and timely medical care plays an important role in children’s health status. However, other factors, including parental influences, nutrition, environmental hazards, community safety, and the overall quality of home life, exert even stronger influences over a child’s well-being. Childhood is generally a healthy time of life, as evidenced by the improvement in many indicators of child health status over the past century. For example, the incidence of childhood disease has decreased because the majority of children receive a full complement of immunizations during infancy and toddlerhood.

The causes of childhood death vary with age. Parents and the community have important responsibilities in promoting healthy lifestyles, creating safe environments, and ensuring access to medical care. They must take steps to protect children from the leading threats to children’s health (i.e., accidental injury and exposure to environmental toxins, abuse, and violence). Box 16-4 discusses screening newborns for genetic disorders.

Accidental Injuries

Infants and young children are at great risk for accidental injuries. They are curious and eager to explore their environments, but they often lack the coordination and cognitive abilities to keep themselves safe from harm. Their small size and developing bones and muscles make them especially susceptible to injury. The leading cause of injury death for children under the age of 1 year is accidental suffocation due to choking or strangulation (CDC, 2008).

Motor vehicle injuries are the leading cause of death for children over the age of 1 year in the United States (CDC, 2008). Many injuries occur because adults fail to secure children in car seats in the back seat of the vehicle or to insist that older children buckle up. The most important step that a parent can take to ensure children’s safety in a motor vehicle is to correctly secure them into car seats, or seat belts when they are older, for each ride. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration recommends booster seats for children until they are at least 8 years of age or 4 feet 9 inches tall (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2009). The risk for motor vehicle accidents is highest for teens aged 16 to 19 years. Not wearing seat belts and drinking and driving contribute dramatically to this risk.

Traumatic brain injury is a leading cause of injury for adolescents, accounting for more than 240,000 emergency room visits, 36,000 hospitalizations, and more than 5700 deaths each year (CDC, 2008). High school sports–related concussions are an important contributor. Head injury from cycling and other wheeled sports, such as skateboarding, is a leading cause of child death and disability. Without proper head protection, a fall from as little as 2 feet can cause traumatic brain injury. The use of helmets and proper protective equipment can substantially reduce the risk of injuries. Other leading causes of accidental injury in children include pedestrian accidents, drowning, and burns. Box 16-5 discusses how toys can be another threat to small children.

Obesity

Obesity is a genuine health crisis in this country. With approximately 23 million children overweight or obese, this could be the first generation to lead sicker, shorter lives than their parents. (Levi et al., 2008)

Seventeen percent of children between the ages of 6 and 17 years are obese (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2008). The percentage of obese children has nearly tripled since 1980. African-American children, particularly those living in the rural South, have the highest obesity levels. Minority groups, those with less income, and those with lower education levels are more likely to be overweight (Levi et al., 2008). The higher cost of healthy foods, food insecurity, and the lack of access to safe places to exercise contribute to obesity in lower-income communities (Widome et al., 2009).

Obesity in children is calculated on the basis of growth charts, physical development, gender, and age. Children at or above the 95th percentile are defined as obese. Those between the 85th and 95th percentile are overweight. Children at the 99th percentile or above are severely obese. Being overweight in childhood can lead to childhood type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The American Diabetes Association describes type 2 diabetes as a “new epidemic” among American children. Although there are a number of genetic risk factors associated with childhood type 2 diabetes, obesity is largely driving the trend toward this serious disease. In addition, overweight children often face social discrimination, which may lead to poor self-esteem and depression. Further, overweight adolescents are more likely to become obese adults. Obesity in adulthood can lead to a number of health problems, including hypertension, coronary disease, and diabetes.

A number of factors contribute to childhood obesity. The typical American diet, which is high in fat and calories and low in nutrients, has resulted in an increase in obesity. Widely available fast food, increasing portion sizes, vending machines in schools, sugar-sweetened drinks, and fewer meals eaten at home have contributed to the trend. Modern technologies such as electronic games, television, and readily accessible transportation have also contributed to more sedentary lifestyles.

Nurses can play a leading role in generating public awareness of factors that contribute to obesity, and focus on preventative measures is key. For example, breastfeeding provides some protection against later obesity. At least 60 minutes of moderately strenuous exercise is recommended for children most days of the week. Nurses can design and implement nutrition, healthy eating, and physical activities policies and standards in schools, and challenge policymakers and industry leaders such as fast-food restaurants to mobilize resources for good nutrition and fitness.

Immunization

Childhood immunization is a benchmark of child health. Maintaining appropriate immunization protects all members of the community, especially immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women who are particularly vulnerable to certain infectious diseases. Adequate immunization protects children against several diseases that kill or disable many children. Polio, a crippling disease of the past, has been eliminated in the United States thanks to the public health effort that made the polio vaccine accessible and affordable. Over the ensuing decades, new vaccines have been developed and children can now be protected from more than fourteen vaccine-preventable diseases. State laws requiring proof of vaccination before entry to school or child care have helped to ensure high vaccination levels.

Vaccine-preventable disease levels are at or near record lows, but many children and adolescents remain underimmunized. Widespread fears that childhood vaccines are linked to autism have prevented some parents from vaccinating their children. In 2009, however, the U.S. Court of Federal Claims ruled that childhood vaccines do not cause autism. This ruling is consistent with eighteen major scientific studies that have failed to show a link between vaccines and autism (U.S. Court of Federal Claims, 2009). Nurses can help to educate community members about the safety of vaccines and the consequences of undervaccination. The following vaccines are recommended for children and adolescents (CDC, 2009c):

• Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine

• Rotavirus vaccine (for selected populations)

• Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine

• Varicella (chickenpox) vaccine

• Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine (Hib)

• Influenza (yearly, for selected populations)

• Pneumococcal vaccine (for selected populations)

• Meningococcal vaccine (for selected populations)

• Human papilloma vaccine (for selected female adolescent populations)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree