Drugs Used for Parkinson’s Disease

Objectives

1 Identify the signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

8 Describe the symptoms that can be attributed to the cholinergic activity of pharmacologic agents.

Key Terms

Parkinson’s disease ( ) (p. 224)

) (p. 224)

dopamine ( ) (p. 224)

) (p. 224)

neurotransmitter ( ) (p. 224)

) (p. 224)

acetylcholine ( ) (p. 224)

) (p. 224)

anticholinergic agents ( ) (p. 226)

) (p. 226)

tremors ( ) (p. 227)

) (p. 227)

dyskinesia ( ) (p. 227)

) (p. 227)

propulsive, uncontrolled movement ( ) (p. 228)

) (p. 228)

akinesia ( ) (p. 228)

) (p. 228)

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease is a chronic progressive disorder of the central nervous system. It is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s disease. An estimated 1% of the U.S. population that is more than 50 years old, 2% of the population that is more than 60 years old, and 4% to 5% of the population 85 years old or older have this disorder. Thirty percent of patients report an onset of symptoms before the age of 50 years; 40% report that the onset occurred between the ages of 50 and 60 years; and the remainder reports that their symptoms began after the age of 60 years. The incidence is slightly higher in men than women, and all races and ethnic groups are affected. Characteristic motor symptoms include muscle tremors, slowness of movement when performing daily activities (i.e., bradykinesia), muscle weakness with rigidity, and alterations in posture and equilibrium. The symptoms associated with parkinsonism are caused by a deterioration of the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, which results in a depletion of dopamine along the nigrostriatal pathway that extends into neurons in the autonomic ganglia, the basal ganglia, and the spinal cord and causes progressive neurologic deficits. These areas of the brain are responsible for maintaining posture and muscle tone, as well as for regulating voluntary smooth muscle activity and other nonmotor activities. Normally, a balance exists between dopamine, which is an inhibitory neurotransmitter, and acetylcholine, which is an excitatory neurotransmitter. With a deficiency of dopamine, a relative increase in acetylcholine activity occurs and causes the symptoms of parkinsonism. About 80% of the dopamine in the neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta of the brain must be depleted for symptoms to develop. Orthostatic hypotension, nocturnal sleep disturbances with daytime somnolence, depression, and progressing dementia are often nonmotor symptoms that are associated with Parkinson’s disease.

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

There are two types of parkinsonism. Primary or idiopathic parkinsonism is caused by a reduction in dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta. The causes are not yet known, but there appear to be both genetic and environmental factors associated with its development. Approximately 10% to 15% of cases appear to be inherited. Secondary parkinsonism is caused by head trauma, intracranial infections, tumors, and drug exposure. Medicines that deplete dopamine and thus cause secondary parkinsonism include dopamine antagonists such as haloperidol, phenothiazines, reserpine, methyldopa, and metoclopramide. In most cases of drug-induced parkinsonism, recovery is complete if the drug is discontinued.

All drugs that are prescribed for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease produce a pharmacologic effect on the central nervous system. An assessment of the patient’s mental status and physical functioning before the initiation of therapy is essential to serve as a baseline so that comparisons can be made with subsequent evaluations.

Parkinson’s disease is, at present, both progressive and incurable. The goals of treatment are to moderate the symptoms and to slow the progression of the disease. It is important to encourage the patient to take the medications as scheduled and to stay as active and involved in daily activities as possible.

Orthostatic hypotension is common with most of the medicines that are used to treat Parkinson’s disease. To provide for patient safety, teach the patient to rise slowly from a supine or sitting position, and encourage the patient to sit or lie down if he or she is feeling faint.

Constipation is a frequent problem among patients with Parkinson’s disease. Instruct the patient to drink six to eight 8-ounce glasses of liquid daily and to increase bulk in the diet to prevent constipation. Bulk-forming laxatives may also need to be added to the daily regimen.

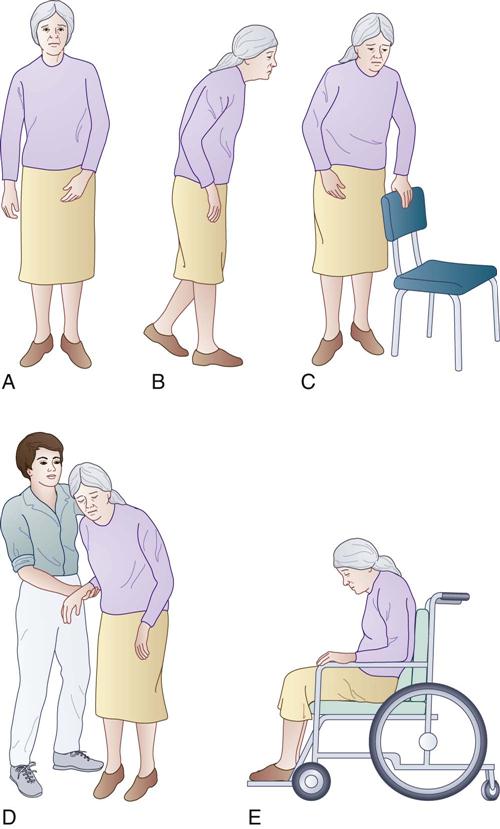

The motor symptoms of parkinsonism start insidiously and are almost imperceptible at first, with weakness and tremors gradually progressing to involve movement disorders throughout the body (Figure 15-1). The symptoms usually begin on one side of the body (i.e., asymmetrical onset and progression) as a tremor of a finger or hand, and they then progress to become bilateral. The upper part of the body is usually affected first. Eventually, the individual has postural and gait alterations that result in the need for assistance with total care needs. Varying degrees of depression are the most common (i.e., 40% to 50%) nonmotor symptom associated with Parkinson’s disease. Most patients with depression also develop feelings of anxiety, and this sometimes includes panic attacks. Those who develop anxiety before depression are very susceptible to depressive episodes after the anxiety. Apathy or depressed emotions with a lack of willpower or the inability to make decisions often accompany depression. Chronic fatigue, which is another common symptom, may also contribute to depression. Dementia, which resembles Alzheimer’s disease, occurs in a significant number of patients, but there is continuing debate as to whether it is part of the Parkinson’s disease process or if it is caused by concurrent drug therapy, Alzheimer’s disease, or other factors. Dementia is characterized by the slowing of the thought processes, lapses in memory, and a loss of impulse control. The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease is based on a careful history taking, a physical examination, and a positive response to dopaminergic treatment. There are no laboratory tests or imaging studies that can confirm the diagnosis.

The patient and the family should understand that Parkinson’s disease often has a course that takes place over decades; that the rate of progression varies greatly from one person to another; and that many approaches are available to reduce symptoms. Patients should be counseled about exercise, including stretching, strengthening, cardiovascular fitness, and balance training. Patients and their families often need assistance to learn about the medical regimen that is used to control the disease’s symptoms and about how to maintain the patient at an optimal level of participation in activities of daily living (ADLs). Drug therapy presents the potential for many adverse effects that all involved parties must understand.

Nurses can have a major influence in the positive use of coping mechanisms as the patient and family express varying degrees of anxiety, frustration, hostility, conflict, and fear. The primary goal of nursing intervention should be to keep the patient socially interactive and participating in daily activities. This can be accomplished through physical therapy, adherence to the drug regimen, and management of the course of treatment.

Drug Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease

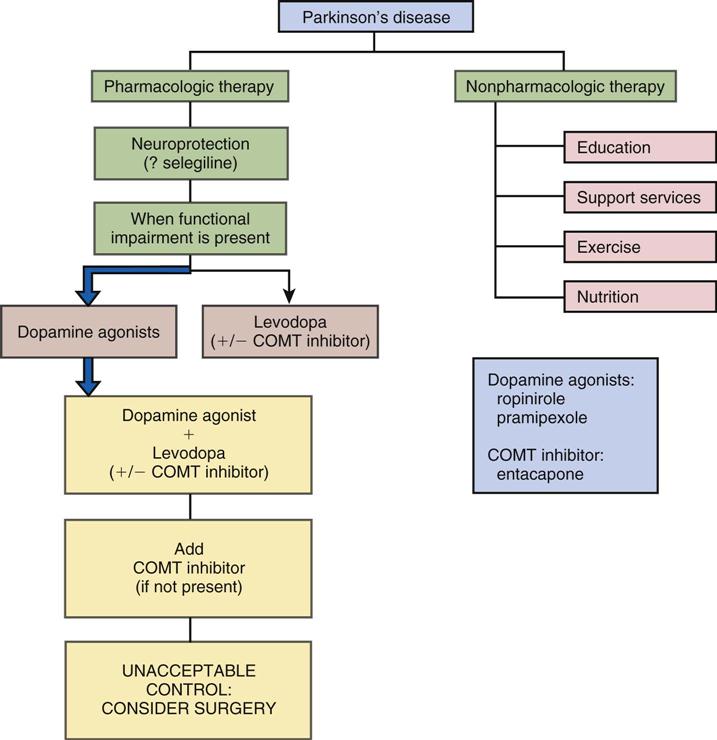

Actions

The goal of the treatment of parkinsonism is minimizing the symptoms, because there is no cure for the disease. Nonpharmacologic therapy focuses on education, support services, exercise, and nutrition. Pharmacologic goals are to relieve symptoms and to restore dopaminergic activity and neurotransmitter function to as close to normal as possible. Treatment is usually started when symptoms progress to interfere with the patient’s ability to perform at work or to function in social situations. Drug therapy includes the use of the following: rasagiline or selegiline, possibly to slow the deterioration of dopaminergic nerve cells; carbidopa-levodopa, ropinirole, pramipexole, amantadine, or entacapone in various combinations to enhance dopaminergic activity; and anticholinergic agents to inhibit the relative excess of cholinergic activity (e.g., tremor). Therapy must be individualized, and realistic goals must be set for each patient. It is not possible to eliminate all symptoms of the disease, because the medications’ adverse effects would not be tolerated. The trend is to use the lowest possible dose of medication so that, as the disease progresses, dosages can be increased and other medicines added to obtain a combined effect. Unfortunately, as the disease progresses, drug therapy becomes more complex in terms of the number of medicines, dosage adjustments, the frequency of dosage administration, and the frequency of adverse effects. Therapies often have to be discontinued because of the impact of adverse effects on the quality of life. Other drug therapy may also be necessary for the treatment of the nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

Uses

Rasagiline or selegiline may be used to slow the course of Parkinson’s disease by possibly slowing the progression of the deterioration of dopaminergic nerve cells. A dopamine receptor agonist—often carbidopa-levodopa—is initiated when the patient develops functional impairment. Carbidopa-levodopa continues to be the most effective drug for the relief of symptoms; however, after 3 to 5 years, the drug’s effect gradually wears off, and the patient suffers from “on–off” fluctuations in levodopa activity. A catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor (entacapone) may be added to carbidopa-levodopa therapy to prolong the activity of the dopamine by slowing its rate of metabolism. Apomorphine may also be administered to treat off periods. Anticholinergic agents provide symptomatic relief from excessive acetylcholine. These agents are often used in combination to promote optimal levels of motor function (e.g., to improve gait, posture, or speech) and to decrease disease symptoms (e.g., tremors, rigidity, drooling). See Figure 15-2 for an algorithm for the treatment for Parkinson’s disease.

Nursing Implications for Parkinson’s Disease Therapy

Nursing Implications for Parkinson’s Disease Therapy

Assessment

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) is often used to identify the baseline of Parkinson’s disease symptoms at the time of diagnosis and to monitor changes in symptoms that may require medicine dosage adjustment. The UPDRS evaluates the following: (1) mentation, behavior, and mood; (2) ADLs; (3) motor examination; (4) complications of therapy; (5) modified Hoehn and Yahr staging; and (6) the Schwab and England ADL scale.

History of Parkinsonism.

Obtain a history of the patient’s exposure to known conditions associated with the development of parkinsonian symptoms, such as head trauma, encephalitis, tumors, and drug exposure (e.g., phenothiazines, reserpine, methyldopa, metoclopramide). In addition, ask if the person has a history of being exposed to toxic levels of metals or carbon monoxide.

Obtain data to classify the extent of parkinsonism that the patient is exhibiting. A rating scale such as the UPDRS may be used to assess the severity of Parkinson’s disease on the basis of the degree of disability exhibited by the patient:

Motor Function.

Patients with Parkinson’s disease progress through the following symptoms.

Tremor.

Tremors are initially so minor that they are observed only by the patient. They occur primarily when the individual is at rest, but they are more noticeable during emotional turmoil or periods of increased concentration. The tremors are often observed in the hands and may involve the jaw, lips, and tongue. A “pill rolling” motion in the fingers and thumbs is characteristic. Tremors are usually reduced with voluntary movement. Emotional stress and fatigue may increase the frequency of tremors.

Assess the degree of tremor involvement and specific limitations in activities that are being affected by the tremors. Obtain a history of the progression of the symptoms from the patient.

Dyskinesia.

Dyskinesia is the impairment of the individual’s ability to perform voluntary movements. This symptom commonly starts in one arm or hand. It is usually most noticeable because the patient ceases to swing the arm on the affected side while walking.

As dyskinesia progresses, movement—especially in the small muscle groups—becomes slow and jerky. This motion is often referred to as cogwheel rigidity. Muscle soreness, fatigue, and pain are associated with the prolonged muscle contractibility. The patient develops a shuffling gait and may have difficulty with halting steps while walking (i.e., festination). When starting movement, there may be brief moments of immobility called freezing. Movements that were formerly automatic, such as getting out of a chair or walking, require a concentrated effort.

In addition to the shuffling gait, the head and spine flex forward, and the shoulders become rounded and stooped. As mobility deteriorates, the steps quicken and become shorter. Propulsive, uncontrolled movement forward or backward is evident, and patient safety becomes a primary consideration. Obtain antislip pads for chairs and other positioning devices. Perform a safety check of the patient’s environment to prevent accidents.

Bradykinesia.

Bradykinesia is the extremely slow body movement that may eventually progress to akinesia (i.e., a lack of movement).

Facial Appearance.

The patient typically appears to be expressionless, as if wearing a mask; the eyes are wide open and fixed in position. Some patients have almost total eyelid closure.

Nutrition.

Complete an assessment of the person’s dietary habits, any recent weight loss, and any difficulties with eating.

Salivation.

As a result of excessive cholinergic activity, patients will salivate profusely. As the disease progresses, patients may be unable to swallow all secretions, and they will frequently drool. If the pharyngeal muscles are involved, the patient will have difficulty chewing and swallowing.

Psychological.

The chronic nature of the disease and its associated physical impairment produce mood swings and serious depression. Patients commonly display a delayed reaction time. Dementia affects the intellectual capacity of about one third of patients.

Stress.

Obtain a detailed history of the manner in which the patient has controlled his or her physical and mental stress.

Safety and Self-Care.

Assess the level of assistance that is needed by the patient for mobility and for the performance of ADLs and self-care.

Family Resources.

Determine what family resources are available as well as the closeness of the family during both daily and stress-producing events.

Implementation

• Reinforce the principles that are taught for gait training.

• Encourage self-maintenance and social involvement.

• Provide a restful environment, and attempt to keep stressors at a minimum.

• Provide for patient safety during ambulation and delivery of care.

• Stress that the effectiveness of medication therapy may take several weeks.

Patient Education

Patient Education

Nutrition.

Teach the patient to drink at least six to eight glasses of water or fluid per day to maintain adequate hydration. Because constipation is often a problem, instruct the patient to include bulk in the diet and to use stool softeners as needed. As the disease progresses, the type and consistency of the foods eaten will need to be adjusted to meet the individual’s needs. Because of fatigue and difficulty with eating, give assistance that is appropriate to the patient’s degree of impairment. Do not rush the individual when he or she is eating, and cut foods into bite-sized pieces. Teach swallowing techniques to prevent aspiration. Plan six smaller meals daily rather than three larger meals.

Instruct the patient to weigh himself or herself weekly. Ask the patient to state the guidelines for weight loss or gain that should be reported to the health care provider.

Stress that vitamins should not be taken unless they have been prescribed by the health care provider. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) will reduce the therapeutic effect of levodopa.

Stress Management.

Explain to the patient and caregivers about the importance of maintaining an environment that is as free from stress as possible. Explain that symptoms such as tremors are enhanced by anxiety.

Self-Reliance.

Encourage patients to perform as many ADLs as they can. Parkinson’s disease is a progressive disorder; explain to caregivers that it is important not to take over and that they should encourage patients’ self-maintenance, continued social involvement, and participation in activities such as hobbies. Use adaptive devices to help the patient with dressing, and purchase clothing with easy closures or fasteners such as Velcro. As mobility diminishes, use a bath chair and handheld shower nozzle to help the patient maintain his or her cleanliness.

Exercise.

Instruct the patient and caregiver about the importance of maintaining correct body alignment, walking as erect as possible, and practicing the gait training taught by the physical therapy department. Gait training is essential if the patient is to delay the onset of shuffling and gait propulsion. Patients should wear sturdy, supportive shoes and use a cane, walker, or other assistive device to maintain mobility. Exercises to maintain the strength of facial muscles and of the tongue help the patient to maintain speech clarity as well as the ability to swallow. Active and passive range-of-motion exercises of all joints help to minimize deformities. Explain that maintaining the exercise program can increase the patient’s long-term well-being.

Mood Alterations.

Explain to the patient and the caregiver that depression and mood alterations are secondary to disease progression (e.g., inability to participate in sex, immobility, incontinence) and are to be expected. Changes in mental outlook should be discussed with the health care provider.

Fostering Health Maintenance.

Provide the patient and his or her significant others with important information contained in the specific drug monographs for the medicines that are prescribed, including the name of the medication; its dosage, route, and administration time; potential adverse effects; and drug-specific patient education. Stress the importance of nonpharmacologic interventions and the long-term effects that compliance with the treatment regimen can provide. Additional health teaching and nursing interventions for the adverse effects of these medications are described in the drug monographs that follow.

Provide information to the patient, family, and caregivers about resources, including the American Parkinson’s Disease Association and the services and information available from this source. There are support groups for patients and families that can serve as caring environments for people with similar experiences and concerns. Respite care may also be available, which provides temporary services to the dependent older adult either at home or in an institutional setting to provide the family with relief from the demands of daily patient care.

Written Record.

Enlist the patient’s help with developing and maintaining a written record of monitoring parameters (e.g., degree of tremor relief, stability, changes in mobility and rigidity, sedation, constipation, drowsiness, mental alertness, deviations from the norm); see the Patient Self-Assessment Form for Antiparkinson Agents on the Evolve Web site![]() . Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track the patient’s response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form, and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions that have been prescribed.

. Complete the Premedication Data column for use as a baseline to track the patient’s response to drug therapy. Ensure that the patient understands how to use the form, and instruct the patient to bring the completed form to follow-up visits. During follow-up visits, focus on issues that will foster adherence with the therapeutic interventions that have been prescribed.

Drug Class: Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors Type B

Actions

Selegiline and rasagiline are potent monoamine oxidase inhibitors type B (MAOI-Bs) that reduce the metabolism of dopamine in the brain, thus allowing for greater dopaminergic activity. Although they are still under investigation, these agents may also be neuroprotective, which means that they may slow the rate of deterioration of the dopamine neurons with the use of other unknown mechanisms.

Uses

Carbidopa-levodopa is the current combination of drugs of choice for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Unfortunately, these agents lose effectiveness (i.e., the on–off phenomenon) and develop more adverse effects (i.e., dyskinesias) over time. It is often necessary to add other dopamine receptor agonists (e.g., pramipexole, ropinirole) or a COMT inhibitor (e.g., entacapone) to improve the patient’s response and tolerance. The MAOI-Bs have similar adjunctive activity to carbidopa-levodopa for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. The combination of either MAOI-B with carbidopa-levodopa improves memory and motor speed, and it may also increase life expectancy.

These agents may also have a neuroprotective effect by interfering with the ongoing degeneration of striated dopaminergic neurons. They may be used early during the treatment of Parkinson’s disease to slow the progression of symptoms and to delay the initiation of levodopa therapy. Selegiline was also recently approved for the treatment of depression (see p. 258).

Selegiline and rasagiline have different metabolic pathways and therefore somewhat different adverse effect profiles. Active metabolites of selegiline, when swallowed, are amphetamines that cause cardiovascular and psychiatric adverse effects. The orally disintegrating tablet dosage form allows the drug to be absorbed from the buccal area in the mouth, thereby avoiding much of the formation of the active metabolites. Note the difference in strength between the tablets and the orally disintegrating tablets. A 10-mg tablet of selegiline is approximately equal in potency to a 1.25-mg orally disintegrating tablet of selegiline. Rasagiline is not metabolized to amphetamines, so cardiovascular and psychiatric adverse effects are minimal.

Therapeutic Outcomes

The primary therapeutic outcomes sought from MAOI-Bs for the treatment of parkinsonism are as follows:

Nursing Implications for Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors Type B Therapy

Nursing Implications for Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors Type B Therapy

Premedication Assessment

1 Perform a baseline assessment of parkinsonism with the use of the UPDRS.

2 Obtain a history of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree