Care of Patients with Disorders of the Lower Respiratory System

Objectives

3. Analyze ways a nurse can contribute to prevention and prompt treatment of tuberculosis.

4. Summarize the pathophysiologic changes that occur during an asthma attack.

5. Evaluate problems that occur with aging that may cause a restrictive pulmonary disorder.

2. Review nursing interventions for the tracheostomy patient on oxygen therapy.

3. Teach a patient how to use a peak flowmeter.

Key Terms

aerosols (ĂR-ō-sŏlz, p. 320)

asthma (ĂZ-mă, p. 306)

atelectasis (ă-tĕ-LĔK-tă-sĭs, p. 303)

bronchiectasis (brŏng-kē-ĔK-tă-sĭs, p. 301)

bronchodilators (brŏng-kō-DĪ-lā-tĕrz, p. 317)

cor pulmonale (kŏr pŭl-mō-NĂ-lē, p. 304)

emphysema (ĕm-fĭ-SĒ-mă, p. 303)

health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP) (p. 296)

hemoptysis (hē-MŎP-tĭ-sĭs, p. 299)

hemothorax (hē-mō-THŌ-răks, p. 313)

hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) (p. 297)

intrathoracic (ĭn-tră-thōr-RĂ-sĭk, p. 315)

latent TB infection (LTBI) (p. 298)

leukotriene (lĕw-kō-trī-ēn, p. 320)

nebulizer (NĔ-bū-lī-zĕr, p. 320)

pleurisy (PLŪR-ă-sē, p. 302)

pneumonectomy (nū-mō-NĔK-tō-mē, p. 311)

pneumonia (nū-MŌ-nē-ă, p. 295)

pneumothorax (nū-mō-THŌ-răks, p. 313)

polycythemia (pŏl-ē-sī-THĒ-mē-ă, p. 303)

sarcoidosis (săr-koy-DŌ-sĭs, p. 302)

subcutaneous emphysema (sŭb-kū-TĀ-nē-ĕs ĕm-fĭ-SĒ-mă, p. 315)

thoracentesis (thŏ-ră-sĕn-TĒ-sĭs, p. 302)

thoracotomy (thō-ră-KŎT-ō-mē, p. 315)

thrombolytic (thrŏm-bō-LĬT-ĭk, p. 312)

tuberculosis (TB) (tū-BĔR-kū-LŌ-sĭs, p. 298)

ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) (p. 297)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Respiratory infectious diseases

Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis frequently is an extension of an upper respiratory infection involving the trachea (tracheobronchitis) and is usually viral in origin. Other causes of acute bronchitis include inhalation of physical or chemical agents such as dust, automobile exhaust, industrial fumes, and tobacco smoke.

Early symptoms of acute bronchitis are similar to those of the common cold. In acute bronchitis, the symptoms progress to chest pain, fever, and a dry, hacking, and irritating cough. Later the cough becomes more productive of mucopurulent sputum. The fever may be moderate (≤101° F [38° C]) and accompanied by chills, muscle soreness, and headache. The physician relies on history and signs and symptoms for diagnosis.

Symptomatic treatment includes humidification using either warm or cool moist air. Cough mixtures or bronchodilators are used to reduce coughing and soothe the irritated tracheal and bronchial mucosa. Nutrition and fluid balance should be maintained. Rest is recommended to avoid progression from an acute condition to a chronic one. Antibiotics are used if a sputum culture shows specific organisms.

Influenza

Etiology

Influenza is an acute, highly infectious disease of the upper and lower respiratory tracts that occurs in isolated cases or in epidemics. Every year there are between 25 and 50 million cases resulting in more than 200,000 hospitalizations and between 30,000 and 40,000 deaths. Influenza is caused by three major types (A, B, and C) and numerous subtypes of influenza viruses. Type A is the most virulent and usually affects young adults first and then spreads to the very young and very old in the community. Influenza is spread by direct and indirect contact with infected people by coughing and sneezing and by virus transferred from contaminated hands to objects.

There are emerging infectious diseases that cause flulike symptoms (Box 15-1). Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) appears to be spread by person-to-person contact, whereas avian flu and West Nile virus are spread by vectors such as certain birds and mosquitoes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010).

Pathophysiology

The influenza viruses affect the respiratory mucosa, causing inflammation and necrosis of tissue and shedding of the virus into the secretions. The inflammation may involve the lungs, pharynx, sinuses, and eustachian tubes. The necrotic tissue provides an environment for the growth of bacteria that cause secondary infection.

Signs and Symptoms

The first symptoms of influenza appear suddenly 2 to 3 days after exposure and include headache, fever (often 101° to 103° F [38° to 40° C]), chills, and muscle aches. Sore throat, hacking cough, runny nose, and nasal congestion and light sensitivity, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea can also occur.

Diagnosis

Chest radiographs and auscultation usually show no abnormality. The white cell count is normal or slightly below normal. Diagnosis is usually based on clinical findings. To confirm the diagnosis, viral culture, serology, rapid antigen testing, or polymerase chain reaction and/or immunofluorescence assays must be performed.

Treatment and Nursing Management

Antibiotics are given only if there is evidence of bacterial infection secondary to the viral infection. If a person is known to be at high risk for influenza and has been exposed to type A influenza, the physician may choose to provide prophylaxis with an antiviral agent such as amantadine (Symmetrel), rimantadine (Flumadine), zanamivir (Relenza), or oseltamivir (Tamiflu). These drugs must be started within 48 hours of the start of symptoms.

Uncomplicated influenza usually is managed more effectively by nursing intervention than by drugs or other forms of medical treatment. Nursing interventions for patients with flu symptoms might include:

• Increase oral fluid intake to at least 3000 mL per 24 hours, unless contraindicated.

• Encourage patient to take analgesics when discomfort first appears.

• Saline gargles for a sore throat.

• Administer suppressant cough medicine at bedtime and during the night as prescribed.

• Cater to patient’s food and drink preferences within limits of dietary restrictions.

• Give antipyretics and perform sponge bath and other measures to reduce high fever.

• Splint chest and abdomen with pillow during coughing attacks.

• Apply emollient to lips and nares as needed.

• Clear nostrils as much as possible to prevent mouth breathing.

• Provide for periods of uninterrupted rest.

Pneumonia

Etiology and Pathophysiology

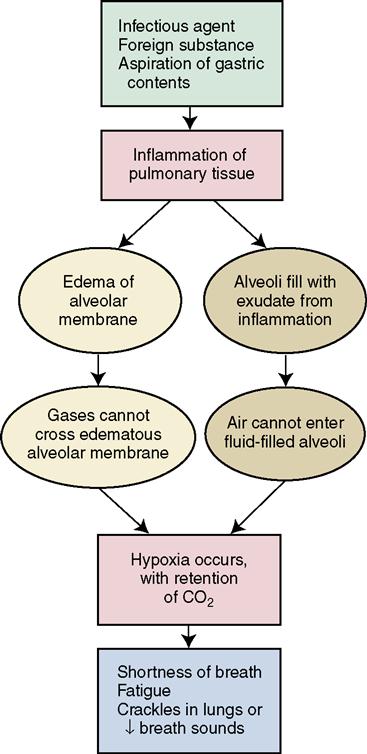

Pneumonia is an extensive inflammation of the lung with either consolidation of the lung tissue as it fills with exudate or interstitial inflammation and edema. It can affect one or both lungs or only one lobe of a lung (lobar pneumonia). In 2006, 55,477 people died of pneumonia; it is the eighth leading cause (combined with influenza) of death in the United States (American Lung Association, 2010a). Pneumonia is classified as community acquired or hospital acquired. Viral pneumonia does not produce exudate; it causes interstitial inflammation and it tends to be less severe than bacterial pneumonia. Bacterial pneumonia usually produces exudate leading to consolidation. It most commonly affects only one lung. Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is the most common cause of bacterial pneumonia. Pathogenic microorganisms are always present in the upper respiratory tract; pneumonia can occur when resistance is lowered by some other factor, such as chronic disease, alcoholism, debilitation, physical inactivity, or extremes in age (very young or very old). Pneumonia frequently occurs after an influenza infection. Concept Map 15-1 presents the pathophysiology of pneumonia.

Pneumonia also can result from inhalation of irritating gases (chemical pneumonia) or accidental aspiration of foods or liquids that cause a pneumonitis progressing to pneumonia (aspiration pneumonia). Hypostatic pneumonia results from lying in bed for extended periods because of lack of physical exercise and inadequate aeration of the lungs. Fungi also may cause opportunistic pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Cytomegalovirus has become a cause of pneumonia in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with AIDS or transplant patients on immunosuppressive drugs.

Prevention

People over age 65, and those with chronic respiratory disease, should receive Pneumovax, the pneumococcal pneumonia vaccine. A second dose may be needed 5 years after the first dose for immunocompromised patients or those over 65 years.

A variety of nursing interventions can help prevent pneumonia, including:

• Strengthening the patient’s natural defenses and avoiding infection.

• Avoiding thin liquids for patients who are at risk for aspiration.

• Encouraging pneumonia vaccine for those most at risk for developing the disease.

Patients are at risk for health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP) (formerly known as nosocomial pneumonia). These at-risk circumstances include hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) where symptoms occur more than 48 hours after admission or ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) where pneumonia occurs 48 to 72 hours after endotracheal intubation. HCAP is also associated with nursing home or long-term care; intravenous therapy, chemotherapy, immunosuppressive treatment, or wound care; severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); or child care facilities, hospitals, or dialysis centers (Atkinson, 2010). HAP is a major problem that lengthens hospital stays and increases the cost of health care. VAP is the second most common hospital-acquired infection; however, vigilant and aggressive nursing and respiratory care can greatly decrease the incidence.

People who are on gastrointestinal acid–suppressive therapy should be educated that this may make them more susceptible to community-acquired pneumonia (Restrepo et al., 2010). Normal gastric acid helps prevent pathogens from colonizing the upper GI tract, where they can then be introduced into the respiratory tract.

Signs, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

In typical infectious pneumonia, there is usually a high fever accompanied by chills, a cough that produces rusty or blood-flecked sputum, sweating, chest pain that is made worse by respiratory movements, and a general feeling of malaise and aching muscles. Diagnosis is confirmed by chest radiograph, which reveals densities in the affected lung.

In atypical pneumonia, body temperature can be normal or subnormal, breath sounds can be normal with perhaps only occasional crackles and wheezes, and there may be no pleural involvement and therefore no pain, dry cough, or feeling of extreme fatigue. Chest radiography reveals diffuse, patchy areas of density.

Treatment

Typical pneumonia is treated with intravenous (IV) or oral antibiotic agents, such as erythromycin or the new macrolides (clarithromycin [Biaxin]), cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, or fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin (Cipro).

Atypical pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma species usually is treated with either erythromycin, clarithromycin, or azithromycin. Viral, atypical pneumonia requires no anti-infective therapy, but antiviral medication may be administered. Pneumocystis jiroveci infection associated with AIDS is treated with aerosolized and intravenous pentamidine, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim), trimetrexate glucuronate (NeuTrexin), dapsone, clindamycin, or atovaquone.

According to the Joint Commission’s Core Measures (2010), the first antibiotic dose should be administered within 6 to 8 hours of presentation whenever the admission  diagnosis is community-acquired pneumonia. The timeliness of this therapy is related to decreased mortality rates. Supplemental oxygen is provided as needed. Some patients require mechanical ventilation.

diagnosis is community-acquired pneumonia. The timeliness of this therapy is related to decreased mortality rates. Supplemental oxygen is provided as needed. Some patients require mechanical ventilation.

Nursing Management

The nursing care plan for a patient with pneumonia should include interventions to:

• Control elevated temperature

• Maintain nutritional and fluid intake

• Monitor vital signs and respiratory status

• Prevent irritation of the lungs by smoke and other irritants

The patient should deep breathe and cough 5 to 10 times each hour while awake. It is important that the nurse assess for signs of increasing impairment of gas exchange. Fluid intake, unless contraindicated, should be increased to 2500 to 3000 mL/day. Because abdominal distention, nausea, and vomiting also may accompany pneumonia, nursing interventions to deal with these problems may be indicated. Other problems include altered states of consciousness (delirium and confusion) or the development of such complications as empyema (see later) and congestive heart failure. For the young adult, convalescence with rest should extend for at least a week after acute symptoms subside. The older adult needs several weeks to do usual activities without undue fatigue.

Empyema

Empyema occurs when the fluid within the pleural cavity becomes infected and the exudate becomes thick and purulent. The organisms causing the infection may be staphylococci or streptococci. One or more chest tubes are inserted and a closed drainage system is established to remove excess fluid from the pleural cavity. A specimen of the fluid is sent for a culture and sensitivity, which determines the choice of antibiotic therapy.

Fungal Infections

The most common fungal lung infections are coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis. Coccidioidomycosis occurs primarily in the western United States and exposure occurs during desert recreational activities or when working in occupations that require digging in the earth. Typically, there are no symptoms or mild respiratory symptoms, but 40% will have cough, fever, pleuritic chest pain, myalgias, and arthralgias. Sometimes a flat red rash with dark red papules occurs. Histoplasmosis occurs in central and eastern portions of North America. The fungus lives in moist soil such as that in which mushrooms grow, on the floors of chicken houses and bat caves, and in bird droppings. Clinical signs are fever, fatigue, cough, dyspnea, and weight loss over 1 to 2 months.

The other fungal infections, such as blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, aspergillosis, and candidiasis, are seen mostly in immunocompromised people or those with cystic fibrosis. Pneumocystis carinii is now considered a fungus, renamed Pneumocystis jiroveci. It is found only in immunocompromised patients and is highly lethal (see Chapter 12). Fungal infections are diagnosed by history, signs and symptoms, and positive skin test reaction to the fungus. Treatment is IV amphotericin B for up to 12 weeks.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Etiology

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease, characterized by lesions within the lung tissue. The lesions may degenerate and become necrotic, or they may heal by fibrosis and calcification. The causative organism is the true tubercle bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Latent TB infection (LTBI) refers to an infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis but no current active disease. LTBI may develop into active TB if the immune system is weakened by a serious illness such as HIV, or when the system is less efficient, as with advanced age.

Contrary to popular belief, TB is not highly contagious. Infection most often occurs after prolonged exposure, but not everyone contracts the disease, even after close and extensive contact with infected persons.

Tuberculosis is a major health problem throughout the world. The increase in the number of immunodeficient people with AIDS, the influx of immigrants who are infected with TB, and an increase in the population of malnourished urban poor are major causes of the increase in the United States.

In countries where there are high rates of TB, the World Health Organization strongly recommends the widespread use of bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, which seems to reduce the morbidity of TB. The vaccine’s ability to increase resistance is in question, so it is not used in the United States.

Pathophysiology

Mycobacterium is an acid-fast, aerobic, slow-growing bacillus. When the organism enters the lungs, a local inflammatory reaction occurs, usually in the upper lobe. Bacilli migrate to the lymph nodes and activate a cell-mediated hypersensitivity response. This triggers granuloma formation with influx of macrophages and lymphocytes at the site of inflammation. The bacillus is walled off, forming a tubercle. Caseation necrosis (a core of cheeselike material) develops in the center of the tubercle. In a healthy person, the tubercles eventually calcify. In the unhealthy individual, the bacilli spread to other parts of the lung and to other organs. Bacilli may remain viable in a dormant state inside the tubercle for many years. The bacilli are difficult to eradicate when released into the environment because the bacillus is resistant to drying and to many disinfectants.

Signs and Symptoms

The onset of TB is gradual; a patient may have an active, progressive lesion before symptoms appear. Typical symptoms are cough, low-grade fever in the afternoon, anorexia, loss of weight, fatigue, night sweats, and sometimes hemoptysis (blood in sputum). Tight or dull chest pain and mucopurulent sputum may occur as the disease progresses. Persons with LTBI are asymptomatic and have a negative chest radiograph.

Diagnosis

Early detection of TB is of great importance because:

• The anti-TB drugs are more effective in the early stages of the disease.

• The period of disability is much shorter.

Tuberculin Skin Testing

Food handlers, those working with children, and health care workers must be periodically tested. Others who are symptomatic or have been exposed to someone with TB should be tested. Skin testing for TB is done by the Mantoux test. In this test, 0.1 mL of purified protein derivative (PPD) tuberculin is injected intradermally. The test is called the tuberculin skin test (TST) (formerly known as PPD test). The test is positive when the swelling at the site of injection is more than 5 mm in diameter 48 to 72 hours after injection in people who have a history of contact with infectious TB or in immunocompromised patients. Induration of more than 10 mm in diameter is positive in recent immigrants from countries where TB is prevalent, in medically underserved groups, and the homeless. For those persons at low risk, induration of more than 15 mm is considered positive. Skin testing is not used on people who have received BCG vaccine within the previous 10 years; this includes those in whom BCG has been used to treat bladder cancer.

A positive tuberculin test indicates that the person has been infected with the tubercle bacillus; however it does not indicate whether the disease is active or inactive, only that the body tissues are sensitive to tuberculin. A positive reaction indicates a need for further evaluation. Once positive, subsequent TSTs will always be positive.

A newer blood test, the QuantiFERON-TB Gold, is less likely to produce false-positive readings. It means one visit to the clinic or office for a blood draw, rather than the two required for the TST (the second visit is for reading the result). It is accurate even for people who have had BCG.

Radiographic Examinations and Sputum Cultures

A radiographic examination of the chest may or may not reveal tubercular lesions in the lung, but calcified and healed lesions can usually be seen on radiographs. A diagnosis of active TB is established when the tubercle bacillus has been found in the sputum or gastric washings. A sample of stomach contents may be examined if the patient cannot produce an adequate sputum specimen (gastric analysis). Sputum cultures are slow growing, and culture results take 1 to 3 weeks to allow identification of the bacillus.

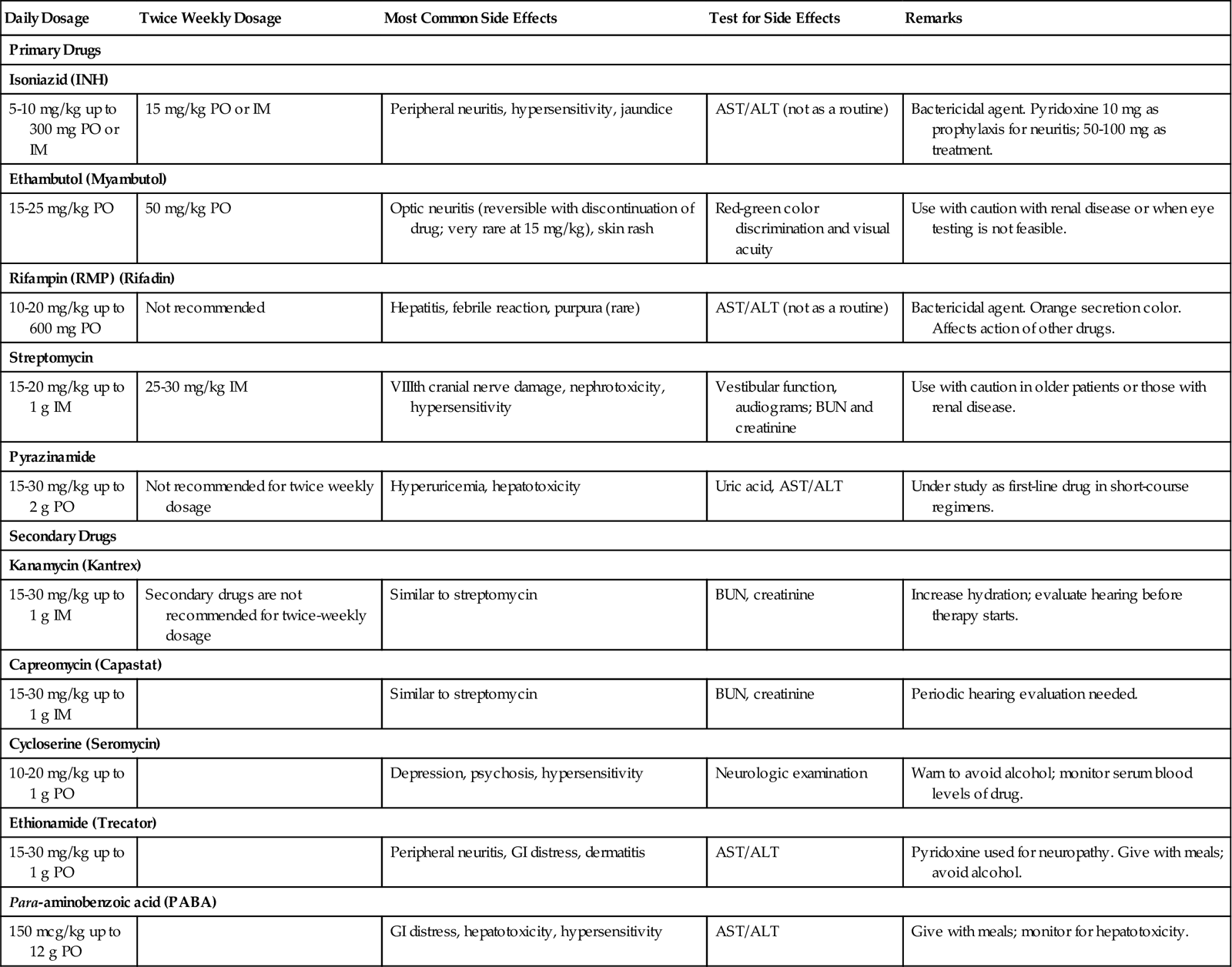

Treatment

Uncomplicated pulmonary TB is managed in the outpatient setting. Only those who are extremely debilitated or suffering from another chronic illness are hospitalized. Treatment consists of at least four drugs for an extended period of time (Table 15-1). The microscopic-observation drug susceptibility (MODS) test described in Chapter 13 is used to determine the best drugs. The drugs are given in varying combinations on varying numbers of days per week. Noncompliance is an issue because of side effects, the requirement to avoid alcohol, and the long duration of therapy. Two new drug combinations have made compliance easier for patients: Rifamate, containing rifampin and isoniazid, and Rifater, containing rifampin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide. Rifapentine (Priftin) may make treatment easier as it is taken once a week during the last four months of therapy, in combination with other drugs. Effective cure can be obtained within 6 to 9 months for most patients with pulmonary TB.

Table 15-1

Table 15-1

Drugs Commonly Used in the Treatment of Tuberculosis

| Daily Dosage | Twice Weekly Dosage | Most Common Side Effects | Test for Side Effects | Remarks |

| Primary Drugs | ||||

| Isoniazid (INH) | ||||

| 5-10 mg/kg up to 300 mg PO or IM | 15 mg/kg PO or IM | Peripheral neuritis, hypersensitivity, jaundice | AST/ALT (not as a routine) | Bactericidal agent. Pyridoxine 10 mg as prophylaxis for neuritis; 50-100 mg as treatment. |

| Ethambutol (Myambutol) | ||||

| 15-25 mg/kg PO | 50 mg/kg PO | Optic neuritis (reversible with discontinuation of drug; very rare at 15 mg/kg), skin rash | Red-green color discrimination and visual acuity | Use with caution with renal disease or when eye testing is not feasible. |

| Rifampin (RMP) (Rifadin) | ||||

| 10-20 mg/kg up to 600 mg PO | Not recommended | Hepatitis, febrile reaction, purpura (rare) | AST/ALT (not as a routine) | Bactericidal agent. Orange secretion color. Affects action of other drugs. |

| Streptomycin | ||||

| 15-20 mg/kg up to 1 g IM | 25-30 mg/kg IM | VIIIth cranial nerve damage, nephrotoxicity, hypersensitivity | Vestibular function, audiograms; BUN and creatinine | Use with caution in older patients or those with renal disease. |

| Pyrazinamide | ||||

| 15-30 mg/kg up to 2 g PO | Not recommended for twice weekly dosage | Hyperuricemia, hepatotoxicity | Uric acid, AST/ALT | Under study as first-line drug in short-course regimens. |

| Secondary Drugs | ||||

| Kanamycin (Kantrex) | ||||

| 15-30 mg/kg up to 1 g IM | Secondary drugs are not recommended for twice-weekly dosage | Similar to streptomycin | BUN, creatinine | Increase hydration; evaluate hearing before therapy starts. |

| Capreomycin (Capastat) | ||||

| 15-30 mg/kg up to 1 g IM | Similar to streptomycin | BUN, creatinine | Periodic hearing evaluation needed. | |

| Cycloserine (Seromycin) | ||||

| 10-20 mg/kg up to 1 g PO | Depression, psychosis, hypersensitivity | Neurologic examination | Warn to avoid alcohol; monitor serum blood levels of drug. | |

| Ethionamide (Trecator) | ||||

| 15-30 mg/kg up to 1 g PO | Peripheral neuritis, GI distress, dermatitis | AST/ALT | Pyridoxine used for neuropathy. Give with meals; avoid alcohol. | |

| Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) | ||||

| 150 mcg/kg up to 12 g PO | GI distress, hepatotoxicity, hypersensitivity | AST/ALT | Give with meals; monitor for hepatotoxicity. | |

Adapted from Lewis, S.L., Heitkemper, M.M., & Dirksen, S.R. (2011). Medical-Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems (8th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

A new drug, PA-824, is in phase II clinical trials and holds promise for shortening the TB treatment regimen (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2009), which could solve some problems related to compliance with TB therapy.

There is an increase in the incidence of multidrug-resistant TB, and patients with these infections do not fare well. For this reason, directly observed therapy (DOT) is recommended for patients who are known to be at risk of noncompliance with therapy (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2009).  DOT involves the visual observation of the ingestion of each required dose of medication for the entire course of treatment. Often a public health nurse administers the medication at a clinic site. Follow-up visits are necessary for 12 months after completion of therapy to monitor for the presence of resistant strains.

DOT involves the visual observation of the ingestion of each required dose of medication for the entire course of treatment. Often a public health nurse administers the medication at a clinic site. Follow-up visits are necessary for 12 months after completion of therapy to monitor for the presence of resistant strains.

Nursing Management

A complete history and assessment of TB risk factors is needed. A focused assessment of the respiratory system is performed (see Focused Assessment on p. 263).

Nursing objectives are to control the spread of the infectious agent, promote immunity, and strengthen potential recovery in a patient with an infectious disease.

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with TB may include:

• Ineffective breathing pattern related to decreased lung capacity

• Activity intolerance related to fatigue, febrile status, and poor nutritional status

• Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to anorexia, fatigue, and productive cough

Control of Infection

Airborne Infection Isolation in addition to Standard Precautions (see Appendix B) is recommended for the hospitalized patient who has an active case of TB and is just beginning drug therapy. The patient is placed in a negative-pressure isolation room with an anteroom. A high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) respirator mask that tightly fits the face is required for all personnel when caring for the patient. The home care patient does not need Airborne Infection Isolation because family members have already been exposed by the time of diagnosis. Patients and families should be educated about the importance of medication compliance and the basic principles of infection control: covering the mouth when coughing or sneezing, disposing of tissues in plastic bags, practicing good hand hygiene, and wearing a mask when in contact with crowds until medication effectively suppresses the infection. Sputum examinations are required every 2 to 4 weeks. When three consecutive sputum cultures are negative, the patient is considered no longer infectious and may resume work and other usual social activities.

Promotion of Immunity

Improving living conditions and carrying out sound health practices are essential to maintaining a natural resistance to TB. Close contacts are monitored with skin testing. Treatment of LTBI (previously called preventive therapy or chemoprophylaxis) is indicated for those at increased risk of progression to active TB. Isoniazid (INH) has a 90% effectiveness. The drug is taken once daily for 9 months; research suggests that a 4-month course of rifampin would improve compliance (Menzies et al., 2008). INH therapy is recommended for:

• Those living with—or closely associating with—a person who is newly diagnosed as having TB.

• People who have positive TST, but who have normal chest radiographs.

A recombinant vaccine—rBCG30—has been developed at the University of California at Los Angeles, and the first clinical trials in humans began in 2004. It is hoped that this vaccine will provide a strong protective immune response against TB (Horowitz, 2010).

Support

When a person first learns that he has tuberculosis, he will need support in sorting out his feelings and overcoming any fears and misinformation he might have.

When a person first learns that he has tuberculosis, he will need support in sorting out his feelings and overcoming any fears and misinformation he might have.

It is also important that the patient name all close contacts, so that they can be notified and appropriately tested and treated. Giving the names of contacts may be very difficult for the patient because of the social stigma that is still attached to TB in certain cultural groups.

Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis

It is possible for the tubercle bacillus to attack and damage parts of the body other than the lungs. This is called extrapulmonary or miliary tuberculosis. The areas most frequently affected are the bones, meninges, urinary system, and reproductive system. Tuberculosis of the spine, called Pott’s disease, can cause kyphosis, or “hunchback,” but the condition is rare in the United States.

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is a chronic respiratory disorder in which one or more bronchi are permanently dilated. It is thought to occur as a result of frequent respiratory infections in childhood.

Cystic Fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a major cause of bronchiectasis. It is a genetic disease (more frequent among whites) in which there is excessive mucus production because of exocrine gland dysfunction. The lungs, intestines, sinuses, reproductive tract, sweat glands, and pancreas are all affected. It is diagnosed by history, physical examination, and a positive sweat test.

Lung damage occurs in cystic fibrosis because of excessive secretion of abnormally thick mucus, impairment of ciliary action in the lungs, airway obstruction, and repeated infections, which cause scarring. It was once a pediatric disease, because children with cystic fibrosis died before reaching adulthood. Cystic fibrosis patients now live into their 40s and beyond with aggressive respiratory treatment and antibiotics. In 1989, the gene responsible for cystic fibrosis was identified (National Human Genome Research Institute, 2009). Work is continuing on ways to isolate and replace the missing gene to prevent or cure the disease.

Treatment includes bronchodilators, expectorants, oral pancreatic enzymes, double doses of fat-soluble vitamins, and mucolytics. A high-protein, high-calorie, moderate-fat diet is prescribed. Dornase alfa (Pulmozyme) reduces the frequency of respiratory infections and improves pulmonary function for patients with CF. Breathing exercises and chest physiotherapy are used daily. A handheld device called the flutter valve; looks like a fat pipe. By exhaling actively into the pipe, the device causes vibrations of the airway walls, loosening secretions so that they can be coughed up. DNase, a recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) medication is used to reduce the number of lung infections, to improve lung function, and to extend the average life span of the CF patient. Lung transplantation is a possible lifesaving measure.

Occupational Lung Disorders

Coal dust, dust from hemp, flax, and cotton processing, and exposure to silica in the air all can cause work-related lung disorders. Asbestos exposure may cause mesothelioma, a rare cancer of the chest lining (Mesothelioma Research Foundation, 2010). Asbestos exposure also causes scarring of lung tissue. The other exposures cause obstruction of small airways or scarring and loss of elasticity and compliance. Occupational history is part of the respiratory assessment.

Interstitial Pulmonary Disease

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a lung disease characterized by granulomas. This disease causes fibrotic changes in the lung tissue and other tissues over time. A cellular immune response seems to be responsible, but the exact cause is unknown. Sarcoidosis is 10 times more common in African Americans than in whites, and most cases occur between ages 20 and 40. The fibrotic changes cause a reduction in function in lung tissue. Although there is no specific treatment for sarcoidosis, occasionally patients recover without treatment.

Pulmonary Fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis occurs from severe infection, repeated infection, or inflammation that causes scarring of the lung tissue. The scarring decreases functional lung tissue. Occupational inhalation of lung irritants, smoking, and chronic aspiration are risk factors. Signs and symptoms are exertional dyspnea, nonproductive cough, and inspiratory crackles, and sometimes clubbed fingers. Diagnosis is by chest radiograph and pulmonary function testing. There is a 30% to 50% survival rate at 5 years after diagnosis. Treatment is with corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and the antifibrotic agent colchicine. Lung transplantation is an option for some patients.

Restrictive pulmonary disorders

Restrictive pulmonary disorders are caused by decreased elasticity or compliance of the lungs, or decreased ability of the chest wall to expand. Disorders of the central nervous system or of the neuromuscular system can cause a restrictive lung disorder. Myasthenia gravis and arthritis are examples of extrapulmonary causes. Kyphosis of the spine or severe scoliosis may hamper lung expansion, but the lung tissue remains normal.

Pleurisy

Pleurisy—an inflammation of the pleura—could be caused by tuberculosis, pneumonia, neoplasm, or pulmonary infarction. Pleurisy pain is sharp and abrupt in onset and is most evident on inspiration. This causes shallow breathing. A pleural friction rub may be heard. Treatment is aimed at the underlying cause and providing pain relief. Lying on the affected side or splinting the affected side during coughing may provide some relief. An intercostal nerve block may be done for severe pleurisy pain.

Pleural Effusion

Pleural effusion is a collection of fluid in the pleural space. Transudate is a thin fluid containing no protein that passes from cells into interstitial spaces or through a membrane. A transudate occurs in noninflammatory conditions and is often a result of congestive heart failure, chronic liver failure, or renal disease. Exudate is thicker, contains cells, proteins, and other substances, and is slowly discharged from cells into a body space or to the outside of the body. Exudative pleural effusion is due to the increased capillary permeability characteristic of the inflammatory reaction. This type of effusion occurs with lung cancer, pulmonary embolism, pancreatic disease, and pulmonary infections.

When pleurisy is accompanied by effusion of serous fluid, the physician may perform a thoracentesis (removal of fluid from the pleural cavity) for diagnostic tests or symptom relief. It is not uncommon for as much as 500 mL to be removed during a thoracentesis (see Table 13-3).

Obstructive pulmonary disorders

Obstructive pulmonary disorders are characterized by problems with moving air in and out of the lungs. Narrowing of the openings in the tracheobronchial tree increases resistance to the flow of air, making it difficult for oxygen to enter; this contributes to air trapping, thus exhalation is also difficult. Asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis are examples of diseases that cause chronic airflow limitation (CAL). The increase in the morbidity and mortality rates due to obstructive disorders is attributed to cigarette smoking and rising levels of air pollution. A third factor is genetic susceptibility to the destruction of lung tissue. Alpha1–antitrypsin (AAT) is a serum protein which inhibits the activity of the enzyme elastase, which tends to break down lung tissue. In the absence of AAT, lung tissue is more easily destroyed by the enzyme. Patients with a deficiency of AAT may develop severe lung disease at an early age.

Atelectasis

Atelectasis is an incomplete expansion, or collapse, of alveoli. It may occur from compression of the lungs from outside, a decrease in surfactant, or bronchial obstruction that prevents air from reaching the alveoli. Postoperatively it occurs from retained secretions that accumulated during anesthesia, positioning on the operating room table for an extended period without movement, and hypoventilation related to surgical pain. It usually is a reversible condition. Breath sounds are diminished when the airways are collapsed, and oxygen saturation (SaO2) will decrease. Treatment consists of expelling secretions by coughing. Deep breathing and use of the incentive spirometer helps to keep the alveoli open and functional.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the term used to describe a condition that includes two diseases, emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Approximately 12.7 million people in the United States have COPD and 24 million have impaired lung function with probable underlying COPD (American Lung Association, 2010b).

Etiology and Diagnosis of COPD

Smoking and AAT deficiency are the primary causes of emphysema and chronic bronchitis, with air pollution and occupational exposure being contributing factors. Diagnosis is by history, physical assessment, chest x-ray, pulmonary function testing, arterial blood gas analysis, and, if needed, lung biopsy.

Emphysema

Pathophysiology

In emphysema, there is destruction of alveolar and alveolar-capillary walls, as well as narrowed and tortuous small airways. This leads to large, permanently inflated alveolar air spaces. Air that is inhaled becomes trapped and it becomes harder to exhale air than to inhale it (Figure 15-1). As emphysema progresses, lung elasticity decreases.

Signs and Symptoms

Dyspnea is an early symptom of emphysema. There is minimal coughing with small amounts of mucoid sputum. As the disease progresses, dyspnea worsens and eventually interferes with activities of daily living. The diaphragm becomes permanently flattened by overdistention of the lungs, the muscles of the rib cage become rigid, and the ribs flare outward. The patient develops a “barrel chest” (see Figure 13-4).

To compensate for the loss of normal muscular action, the patient begins to use the neck and shoulder muscles. The shoulders are held high in an attempt to enlarge the space for lung expansion. The patient may look anxious or tense. The skin is a pink tone in whites even though hypoxia may be present. Carbon dioxide is usually not retained, and therefore an acid-base imbalance is unlikely.

Chronic Bronchitis

Pathophysiology

In chronic bronchitis there is excess secretion of thick, tenacious mucus that decreases ciliary function and interferes with airflow and causes inflammatory damage to the bronchial mucosa. Airways become edematous and narrowed, and air trapping occurs. Initially the larger airways are affected, and then the smaller airways also become obstructed. Inflammation of the bronchi is considered chronic when a recurrent cough is present for at least 3 months of each year for at least 2 years. Respiratory infections occur frequently because the thick mucus provides a growth medium for bacteria.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms can range from a mildly irritating “cigarette” cough in the morning with production of small amounts of sputum to a severe disabling condition. The latter extreme is characterized by increased resistance to airflow, hypoxia, and frequently hypercapnia (excess CO2).

Pulmonary function testing reveals an increased residual volume due to the premature closure of the narrowed airways during exhalation. The patient has a marked increase in partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) levels and a marked decrease in partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) levels. The retention of carbon dioxide and deficiency of oxygen give the skin and/or mucous membranes a reddish blue color. The reddish color is also related to an increase in the red blood cell count (polycythemia) which is an attempt by the body to compensate for chronic hypoxia. Hemoglobin and hematocrit levels are elevated for patients with chronic bronchitis. Table 15-2 presents a comparison of emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

Table 15-2

Comparison of Pulmonary Emphysema and Chronic Bronchitis

| Clinical Features/Characteristics | Emphysema | Chronic Bronchitis |

| Age of Onset (Years) | 40-50 | 30-40 |

| Pathophysiology | Destruction of alveolar walls Loss of elasticity, impaired expiration, hyperinflation | Increased mucous secretion, inflammation and infection, obstruction of airways |

| Health History | Generally healthy | Frequent URI, acute episodes |

| Smoking | Usually | Usually |

| Clinical Features | ||

| Barrel chest | Yes | May be present |

| Weight loss | May be severe in late disease | Infrequent |

| Shortness of breath | Absent early; pronounced late in disease | Early symptom; especially with activity |

| Decreased breath sounds | Yes | Variable |

| Wheezing | Usually absent | Variable |

| Sputum | Absent or develops late in disease | Early sign; frequent infections with purulent sputum |

| Cyanosis | Usually absent; appears late in disease with low PaO2 | Yes; worsens as disease progresses |

| Cor pulmonale | Occasional | Common |

| Polycythemia | May appear in advanced disease | Frequently present |

| Blood gases | Normal until late in disease | May display hypercapnia |

| Hypoxemia frequent | ||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (2009) recommends annual influenza vaccination for the following groups: (CDC, 2009).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (2009) recommends annual influenza vaccination for the following groups: (CDC, 2009).