Theris A. Touhy

Promoting safety

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

After that fall last year when I slipped on the urine in the bathroom, I feel so insecure. I find myself taking small, shuffling steps to avoid falling again, but it makes me feel awkward and clumsy. When I was younger, I never worried about falling, but now I’m so afraid I will break a bone or something.

Betty, age 75

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Identify older adults who are at risk for falls and list several measures to reduce fall risk.

• Discuss the use of assistive technologies to promote self-care, safety, and independence.

• Understand the effects of restraints and discuss appropriate alternatives for safety promotion.

• Identify factors in the environment that contribute to the safety and security of the older person.

• Develop a nursing care plan appropriate for an elder at risk of falling.

Glossary

Orthostatic (postural) hypotension A drop in blood pressure occurring when a person assumes an upright position after being in a lying-down position.

Proprioception Sensations from within the body regarding spatial position and muscular activity.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Promotion of safety

Promotion of safety and fall prevention are public health issues and are addressed in many national initiatives including those from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Council on Aging (NCOA), Joint Commission, National Center for Patient Safety, and Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN). For older adults, promotion of a safe environment and prevention of falls, accidents, and injuries in all settings is essential to optimal function and quality of life. This chapter focuses on falls and fall risk reduction, measures to promote safety without the use of restraints, aids and interventions that are useful when mobility is impaired, and assistive technologies to enhance self-care, safety, and independence. Issues related to transportation and driving as essential aspects of environmental mobility are also included. Activity and exercise are discussed in Chapter 11 and bone and joint problems affecting mobility are discussed in Chapter 18.

Falls and fall risk reduction

Falls are one of the most important geriatric syndromes and the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for people older than 65 years of age. Thirty to forty percent of people 65 years of age or older fall at least once each year (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF], 2012). Nursing home residents, who are more frail, fall frequently (Quigley et al., 2010). Falls among nursing home residents are estimated at 2.6 per year (Gray-Micelli, 2010).

Falls are a significant public health problem. Falls rank as the seventh leading cause of unintentional injury fatality among older adults and the most common cause of nonfatal injuries and hospital admissions for trauma (Gray-Micelli & Quigley, 2012; CDC, 2010a). Falls and their subsequent injuries result in physical and psychosocial consequences. Twenty percent to 30% of people who fall suffer moderate to severe injuries (bruises, hip fractures, traumatic brain injury [TBI]). Estimates are that up to two thirds of falls may be preventable (Lach, 2010). Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) includes several goals related to falls (see the Healthy People box). Box 13-1 presents statistics of falls and fall-related concerns.

Falls are considered a nursing-sensitive quality indicator. Patient falls have been reported to account for at least 40% of all hospital adverse occurrences (Ireland et al., 2010). All falls in the nursing home setting are considered sentinel events and must be reported to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The Joint Commission (JC) has established national patient safety goals (NPSG) for fall reduction in all JC-approved institutions across the health care continuum (Capezuti et al., 2008). In the hospital, falls with resultant fractures, dislocations, and crushing injuries are considered one of the 10 hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) that are not covered under Medicare (www.cms.gov/HospitalAcqCond/06_Hospital-Acquired_Conditions.asp).

Falls are a symptom of a problem and are rarely benign in older people. The etiology of falls is multifactorial; falls may indicate neurological, sensory, cardiac, cognitive, medication, or musculoskeletal problems or impending illness. Episodes of acute illness or exacerbations of chronic illness are times of high fall risk. The presence of dementia increases risk for falls twofold, and individuals with dementia are also at increased risk of major injuries (fracture) related to falls (Oliver et al., 2007).

Consequences of falls

Hip fractures

More than 95% of hip fractures among older adults are caused by falls. Hip fracture is the second leading cause of hospitalization for older people, occurring predominantly in older adults with underlying osteoporosis (Andersen et al., 2010). Hip fractures are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. Only 50% to 60% of patients with hip fractures will recover their prefracture ambulation abilities in the first year postfracture. Older adults who fracture a hip have a five to eight times increased risk of mortality during the first 3 months after hip fracture. This excess mortality persists for 10 years after the fracture and is higher in men. Existing research also suggests that mortality and morbidity limitations are higher in nonwhite people as compared with white people. Most research on hip fractures has been conducted with older women, and further studies of both men and racially and culturally diverse older adults are necessary (Andersen et al., 2010; CDC, 2010a; Haentjens et al., 2010).

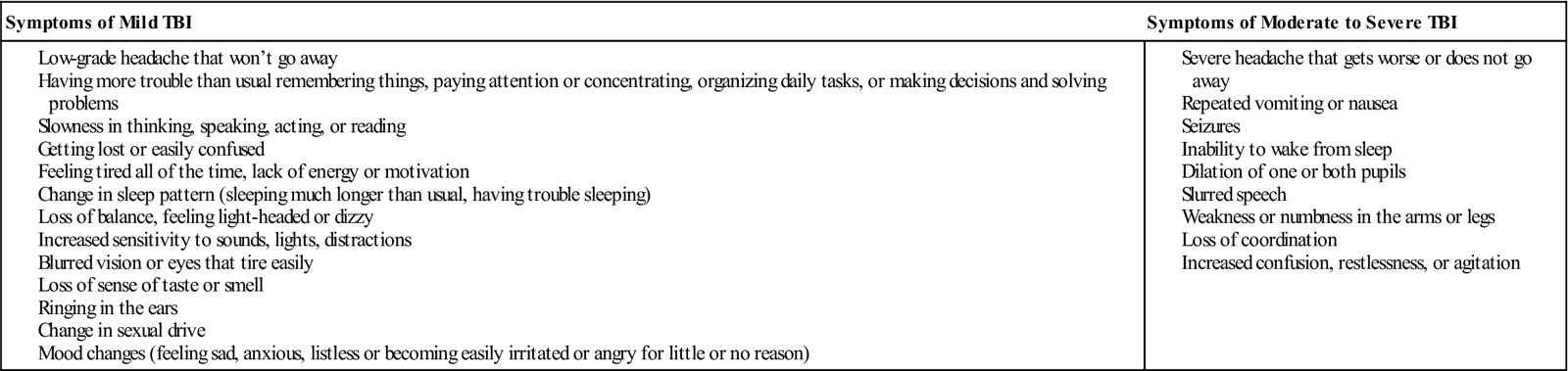

Traumatic brain injury

Older adults (75 years of age and older) have the highest rates of TBI-related hospitalization and death. TBI has been called the “silent epidemic” and older adults with TBI are an even more silent population within this epidemic. Falls are the leading cause of TBI for older adults. Advancing age negatively affects the outcome after TBI, even with relatively minor head injuries (Timmons & Menaker, 2010). A new CDC initiative, Help Seniors Live Better Longer: Prevent Brain Injury, provides educational resource materials on TBI for older adults, caregivers, and health care professionals in both Spanish and English (http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/seniors.html.)

Factors that place the older adult at greater risk for TBI include the presence of comorbid conditions, use of aspirin and anticoagulants, and changes in the brain with age. Brain changes with age, although clinically insignificant, do increase the risk of TBIs and especially subdural hematomas, which are much more common in older adults. There is a decreased adherence of the dura mater to the skull, increased fragility of bridging cerebral veins, and increases in the subarachnoid space and atrophy of the brain, which creates more space within the cranial vault for blood to accumulate before symptoms appear (Timmons & Menaker, 2010). Falls are the leading cause of TBI, but older people may experience TBI with seemingly more minor incidents (e.g., sharp turns or jarring movement of the head). Some patients may not even remember the incident.

In cases of moderate to severe TBI, there will be cognitive and physical sequelae obvious at the time of injury or shortly afterward that will require emergency treatment. However, older adults who experience a minor incident with seemingly lesser trauma to the head often present with more insidious and delayed symptom onset. Because of changes in the aging brain, there is an increased risk for slowly expanding subdural hematomas. TBIs are often missed or misdiagnosed among older adults (CDC, 2010b).

Health professionals should have a high suspicion of TBI in an older adult who falls and strikes the head or experiences even a more minor event, such as sudden twisting of the head For older adults who are receiving warfarin and experience minor head injury with a negative CT scan, a protocol of 24-hour observation followed by a second CT scan is recommended (Menditto et al., 2012). Manifestations of TBI are often misinterpreted as signs of dementia, which can lead to inaccurate prognoses and limit implementation of appropriate treatment (Flanagan et al., 2006). Table 13-1 presents signs and symptoms of TBI.

TABLE 13-1

Signs and Symptoms of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) in Older Adults

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Preventing traumatic brain injury in older adults (2010). Available at www.cdc.gov/BrainInjuryInSeniors.

Fallophobia

Even if a fall does not result in injury, falls contribute to a loss of confidence that leads to reduced physical activity, increased dependency, and social withdrawal (Rubenstein et al., 2003; Hill et al., 2010). Fear of falling (fallophobia) may restrict an individual’s life space (area in which an individual carries on activities). Fear of falling is an important predictor of general functional decline and a risk factor for future falls. Resnick (2002) suggests that nursing staff may also contribute to fear of falling in their patients by telling them not to get up by themselves or by using restrictive devices to keep them from independently moving about. More appropriate nursing responses include assessing fall risk and designing individual interventions and safety plans that will enhance mobility and independence, as well as reduce fall risk.

Factors contributing to falls

Individual risk factors can be categorized as either intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic risk factors are unique to each patient and are associated with factors such as reduced vision and hearing, unsteady gait, cognitive impairment, acute and chronic illnesses, and effect of medications. Extrinsic risk factors are external to the patient and related to the physical environment and include lack of support equipment by bathtubs and toilets, height of beds, condition of floors, poor lighting, inappropriate footwear, improper use of or inadequate assistive devices (Tzeng & Yin, 2008).

Falls in the young-old and the more healthy old occur more frequently because of external reasons; however, with increasing age and comorbid conditions, internal and locomotor reasons become increasingly prevalent as factors contributing to falls. The risk of falling increases with the number of risk factors. Most falls occur from a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors that come together at a certain point in time (Table 13-2).

TABLE 13-2

| Conditions | Situations |

| Sedative and alcohol use, psychoactive medications, opioids, diuretics, anticholinergics, antidepressants, cardiovascular agents, anticoagulants, bowel preparations Four or more medications Unrelieved pain Previous falls and fractures Female, 80 years of age or older Acute and recent illness Cognitive impairment (delirium, dementia) Diabetes Chronic pain Dehydration Weakness of lower extremities Abnormalities of gait and balance Unsteadiness, dizziness, syncope Foot problems Depression, anxiety Decreased vision or hearing Fear of falling Orthostatic hypotension Postprandial drop in blood pressure Decreased weight Sleep disorders Skeletal and neuromuscular changes that predispose to weakness and postural imbalance Functional limitations in self-care activities Inability to rise from a chair without using the arms Slow walking speed Wheelchair-bound | Urinary incontinence, urgency, nocturia Environmental hazards Recent relocation, unfamiliarity with new environment Inadequate response to transfer and toileting needs Assistive devices used for walking Inadequate or missing safety rails, particularly in bathroom Poorly designed or unstable furniture High chairs and beds Uneven floor surfaces Glossy, highly waxed floors Wet, greasy, icy surfaces Inadequate visual support (glare, low wattage bulbs, lack of nightlights) General clutter Inappropriate footwear/clothing Pets that inadvertently trip an individual Electrical cords Loose or uneven stair treads Throw rugs Reaching for a high shelf Inability to reach personal items, lack of access to call bell or inability to use it Side rails, restraints Lack of staff training in fall risk–reduction techniques |

In institutional settings, factors such as limited staffing, lack of toileting programs, and restraints and side rails also interact to increase fall risk. Inadequate staff communication and training, incomplete patient assessments and reassessments, environmental issues, incomplete care planning or delayed care provision, and an inadequate organizational culture of safety have been reported as factors contributing to falls in hospitals (Tzeng & Yin, 2008).

Gait disturbances

Gait disturbances are frequently seen in older people, especially those 85 years of age and older. Marked gait disorders are not normally a consequence of aging alone but are more likely indicative of an underlying pathological condition. Arthritis of the knee may result in ligamentous weakness and instability, causing the legs to give way or collapse. Diabetes, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, alcoholism, and vitamin B deficiencies may cause neurological damage and resultant gait problems.

Foot deformities

Foot deformities and ill-fitting footwear also contribute to gait problems. Care of the feet is an important aspect of mobility, comfort, and a stable gait, and is often neglected (see Chapter 12). Some older persons are unable to walk comfortably, or at all, because of neglect of corns, bunions, and overgrown nails. Other causes of problems may be traced to loss of fat cushioning and resilience with aging, diabetes, ill-fitting shoes, poor arch support, excessively repetitious weight-bearing activities, obesity, or uneven distribution of weight on the feet. As many as 35% of persons living at home may have significant foot disability that goes untended.

Postural and postprandial hypotension

Declines in depth perception, proprioception, vibratory sense, and normotensive response to postural changes are important factors that contribute to falls, although the majority of falls occur in individuals with multiple medical problems. Appropriate assessment of postural changes in pulse and blood pressure is important. Clinically significant postural hypotension (orthostasis) is detected in up to 30% of older people (Tinetti, 2003). Postural hypotension is considered a decrease of 20 mm Hg (or more) in systolic pressure or a decrease of 10 mm Hg (or more) in diastolic pressure.

Assessment of postural hypotension in everyday nursing practice is often overlooked or assessed inaccurately. Postural hypotension is more common in the morning, and therefore assessment should occur then. All older persons should be cautioned against sudden rising from sitting or supine positions, particularly after eating.

Postprandial hypotension (PPH) occurs after ingestion of a carbohydrate meal and may be related to the release of a vasodilatory peptide. PPH is more common in people with diabetes and Parkinson’s disease but has been found in approximately 25% of persons who fall. Lifestyle modifications such as increased water intake before eating or substituting six smaller meals daily for three larger meals may be effective, but further research is needed (Luciano et al., 2010).

Cognitive impairment

Older adults with cognitive impairment, such as dementia and delirium, are at increased risk for falls. Fall risk assessments may need to include more specific cognitive risk factors, and cognitive assessment measures may need to be more frequently scheduled for at-risk individuals. One study (Harrison et al., 2010) reported that use of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) to screen for delirium (see Chapter 21), and the symptom of inattention, has the potential to improve early detection of fall risk in cognitively impaired hospitalized individuals.

Vision and hearing

Formal vision and hearing assessments are important interventions to identify remediable problems. Although a significant relationship exists between visual problems and falls and fractures, little research has been conducted on interventions for visual problems as part of fall–risk reduction programs. Hearing ability is also directly related to fall risk. For someone with only a mild hearing loss, there is a threefold increased chance of having falls (Lin & Ferrucci, 2012).

Implications for gerontological nursing and healthy aging

Screening and assessment

The American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society Clinical Practice Guideline: Prevention of Falls in Older Persons (2010) recommends that all older individuals should be asked whether they have fallen in the past year and whether they experience difficulties with walking or balance. In addition, ask about falls that did not result in an injury and the circumstances of a near fall, mishap, or misstep because this may provide important information for prevention of future falls (Zecevic et al., 2006). Older people may be reluctant to share information about falls for fear of losing independence, so the nurse must use judgment and empathy in eliciting information about falls, assuring the person that there are many modifiable factors to increase safety and help maintain independence.

If the person reports a fall, they should be asked about the frequency and circumstances of the fall(s) and should be evaluated for gait and balance (Figure 13-1). Multifactorial fall risk assessments may be performed depending on the individual circumstances but are not automatically recommended to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults because the likelihood of benefit is small. They may be appropriate for older people who are frail, ill, or have had prior falls (USPSTF, 2012).

Patients who fall present a complex diagnostic challenge and require multifactorial assessment. In the acute and long-term care settings, an interprofessional team (physician, nurse, health care provider, risk manager, physical and occupational therapist, and other designated staff) should be involved in planning care on the basis of findings from an individualized assessment. Attention to modifying risk factors through appropriate medical management is essential, and this may include medication reduction, treatment of cardiac irregularities, cataract surgery, and management of pain.

Assessment is an ongoing process that includes “multiple and continual types of assessment, reassessment, and evaluation following a fall or intervention to reduce the risk of a fall. Assessment includes: (1) assessment of the older adult at risk; (2) nursing assessment of the patient following a fall; (3) assessment of the environment and other situational circumstances upon admission and during institutional stays; (4) assessment of the older adult’s knowledge of falls and their prevention, including willingness to change behavior, if necessary, to prevent falls” (Gray-Micelli, 2008, p. 164).

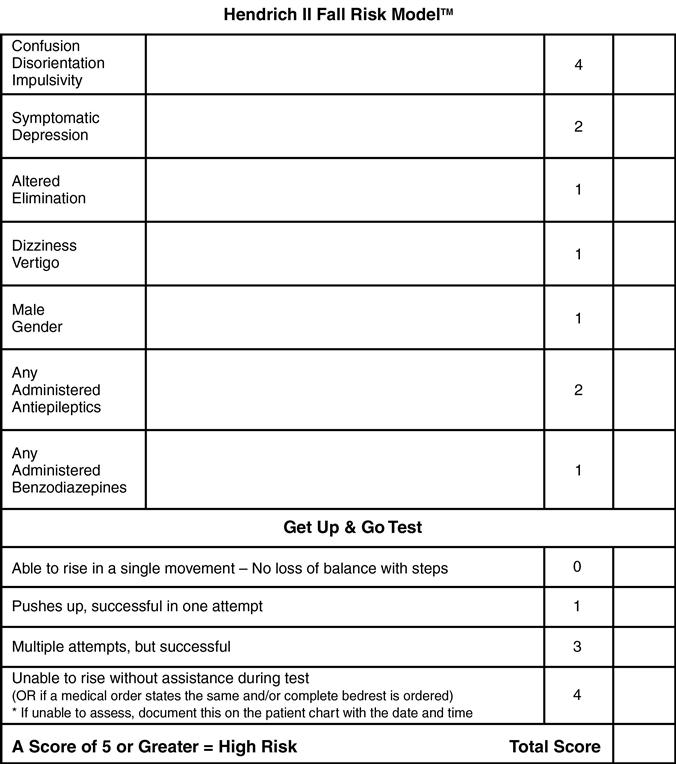

Fall risk assessment instruments

Fall risk is formally assessed through administration of fall risk tools. Instruments that have been evaluated for reliability and validity should be used rather than creating new instruments (Gray-Micelli, 2008; Gray-Micelli & Quigley, 2012). The National Center for Patient Safety recommends the Morse Falls Scale, but not for use in long-term care. The Hendrich II Fall Risk Model (Hendrich et al., 2003) (see Figure 13-1), recommended by the Hartford Foundation for Geriatric Nursing (New York, NY), is an example of an instrument that has been validated with skilled nursing and rehabilitation populations. In the skilled nursing facility, the Minimum Data Set (MDS 3.0) includes information about history of falls and hip fractures as well as an assessment of balance during transitions and walking (moving from seated to standing, walking, turning around, moving on and off toilet, and transfers between bed and chair or wheelchair) (see Chapter 7).

Fall risk assessments provide first-level assessment data as the basis for comprehensive assessment but comprehensive postfall assessments (PFAs) must be used to identify multifactorial, complex fall and injury risk factors in those who have fallen (Gray-Micelli & Quigley, 2012). All assessment data on an individual’s risk for falls must be tailored with individual assessment so that appropriate fall risk–reduction interventions can be developed and modifiable risk factors identified and managed.

The following concerns have been identified related to fall risk assessment instruments:

• The scores used to identify patients at high risk may not be based on research.

• Nurses’ clinical judgment is not considered and may be as effective at identifying high-risk patients as use of fall-risk screening tools (Harrison et al., 2010; Lach, 2010).

Lach (2010) reported that “the problems with fall risk assessment tools caused one author to wonder whether these tools should be ‘put to bed’” (p. 152). Additional research is needed to develop valid, reliable instruments to differentiate levels of fall risk in various settings.

Postfall assessment

Determination of why a fall occurred (postfall assessment [PFA]) is vital and provides information on underlying fall etiologies so that appropriate plans of care can be instituted. Incomplete analysis of the reasons for a fall can result in repeated incidents. “When important details are overlooked, missing information leads to an inappropriate plan of care” (Gray-Micelli, 2008, p. 33). The purpose of the PFA is to identify the clinical status of the person, verify and treat injuries, identify underlying causes of the fall when possible, and assist in implementing appropriate individualized risk-reduction interventions.

PFAs include a fall-focused history; fall circumstances; medical problems; medication review; mobility assessment; vision and hearing assessment; neurological examination (including cognitive assessment); and cardiovascular assessment (orthostatic B/P, cardiac rhythm irregularities) (Gray-Micelli & Quigley, 2012). If the older adult cannot tell you about the circumstances of the fall, information should be obtained from staff or witnesses. Because complications of falls may not occur immediately, all patients should be observed for 48 hours after a fall and vital signs and neurological status monitored for 7 days or more, as clinically indicated. Standard “incident report” forms do not provide adequate postfall assessment information. The Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Patient Safety (http://www.patientsafety.gov/SafetyTopics/fallstoolkit/index.html) provides comprehensive information about fall assessment, fall risk reduction, and policies and procedures. Box 13-2 presents information for a PFA that can be used in health care institutions.

Interventions

Randomized controlled trials support the effectiveness of multicomponent fall prevention strategies in reducing fall risks (Tinetti et al., 2008; Cameron et al., 2010). However, Frick and colleagues (2010) suggest that multifactorial approaches aimed at all older people, or high-risk elders, are not necessarily more cost-effective or better than focused intervention approaches and that further research is needed. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends exercise or physical therapy and vitamin D supplementation to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults (USPSTF, 2012).

Choosing the most appropriate interventions to reduce the risk of falls depends on appropriate assessment at various intervals depending on the person’s changing condition and tailoring to individual cognitive function and language (American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society, 2010). A one-size-fits-all approach is not effective and further research is needed to determine the type, frequency, and timing of interventions best suited for specific populations (community-living, hospital and institutionalized, and racially and culturally diverse older adults).

Ireland and colleagues (2010) also suggest that each institution needs to design strategies to meet organizational needs and to match patient population needs and clinical realities of the staff. Use of the Acute Care of the Elderly (ACE) units; Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders (NICHE) program; and the Geriatric Resource Nurse (GRN) model, which utilize a system-level quality improvement approach, including educational programs for staff, realized a decrease in fall rate by 5.8% (Gray-Micelli & Quigley, 2012) (see Chapter 3).

Box 13-3 presents an innovative fall risk–reduction program, designed by a nurse in an acute care facility that has been adopted around the country and included in fall risk–reduction guidelines. Other innovative programs in nursing homes include the Visiting Angels and neighborhood watch teams. In the Visiting Angels program, alert residents visit and converse with cognitively impaired residents in the late afternoon and evening when fall risk starts to rise. Neighborhood watch teams involve the evening and night staff in morning reviews of any fall or incident that happened during the night (Kilgore, 2010). The components most commonly included in efficacious interventions are shown in Box 13-4. There are many excellent sources of information for both consumers and health care professionals on interventions to reduce fall risk (see the Evidence-Based Practice box).