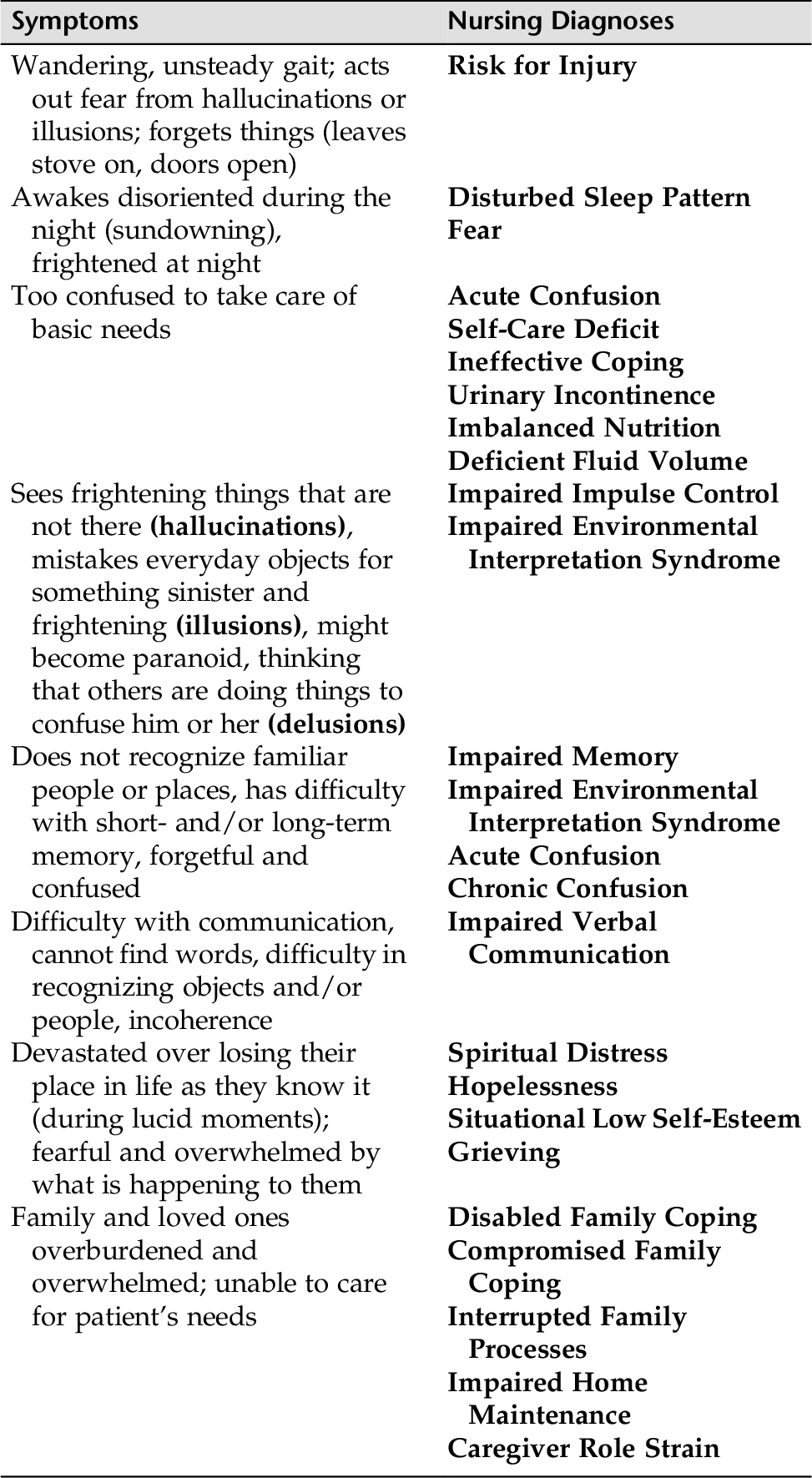

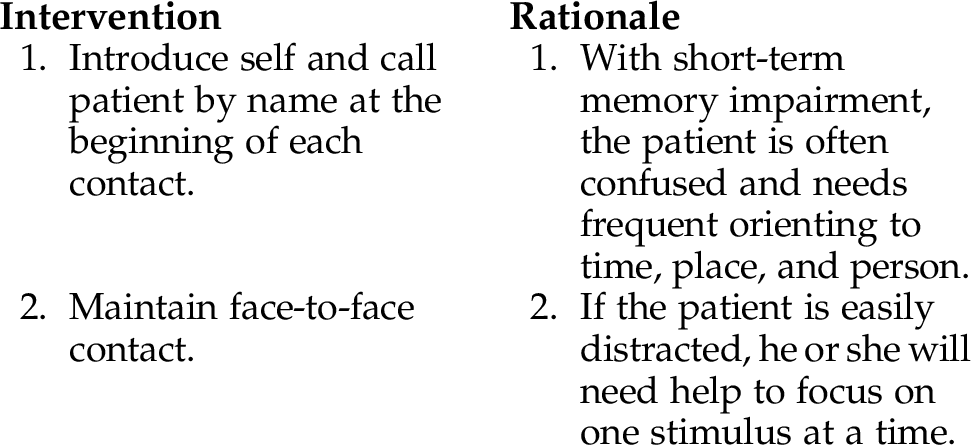

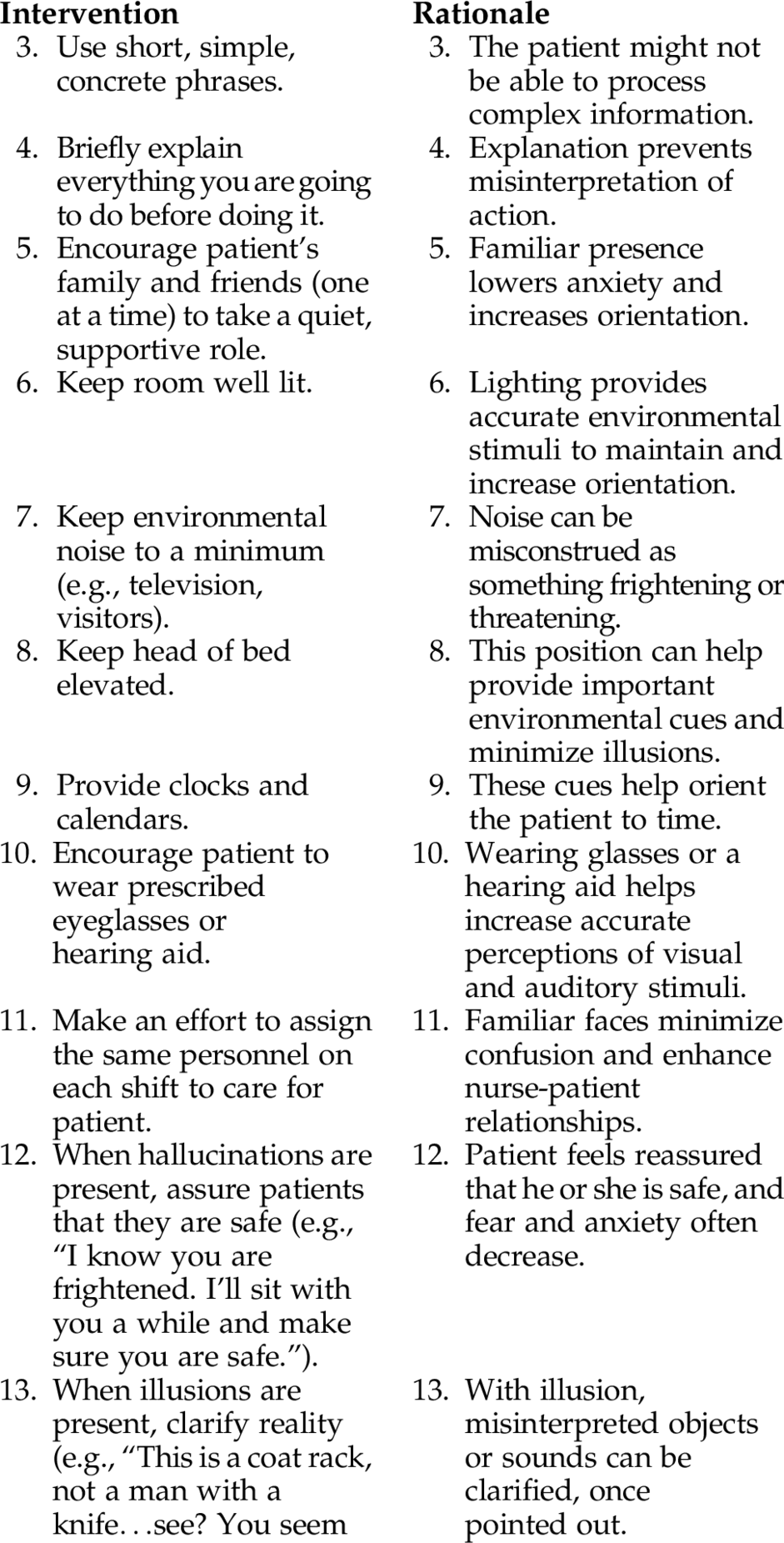

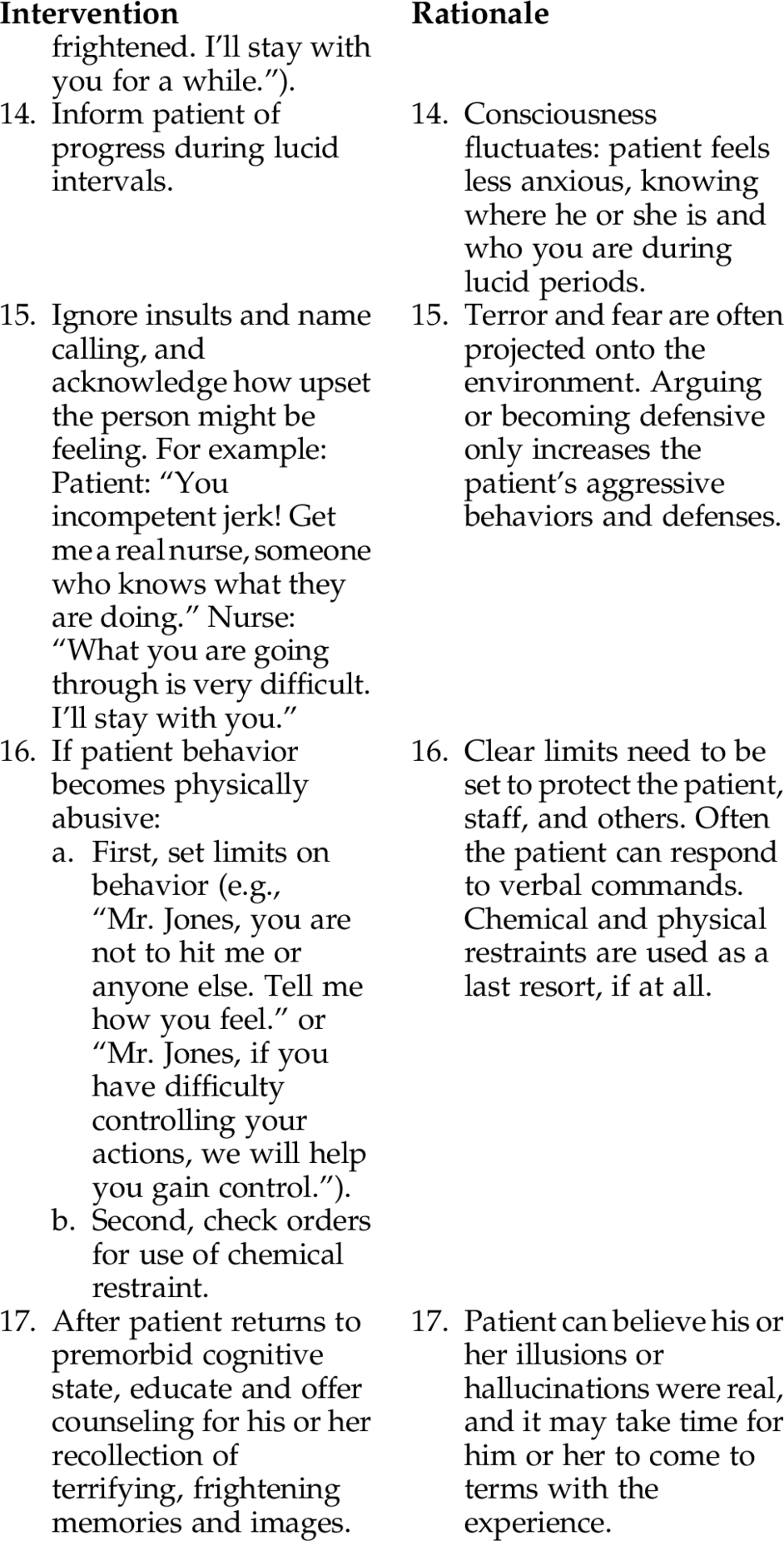

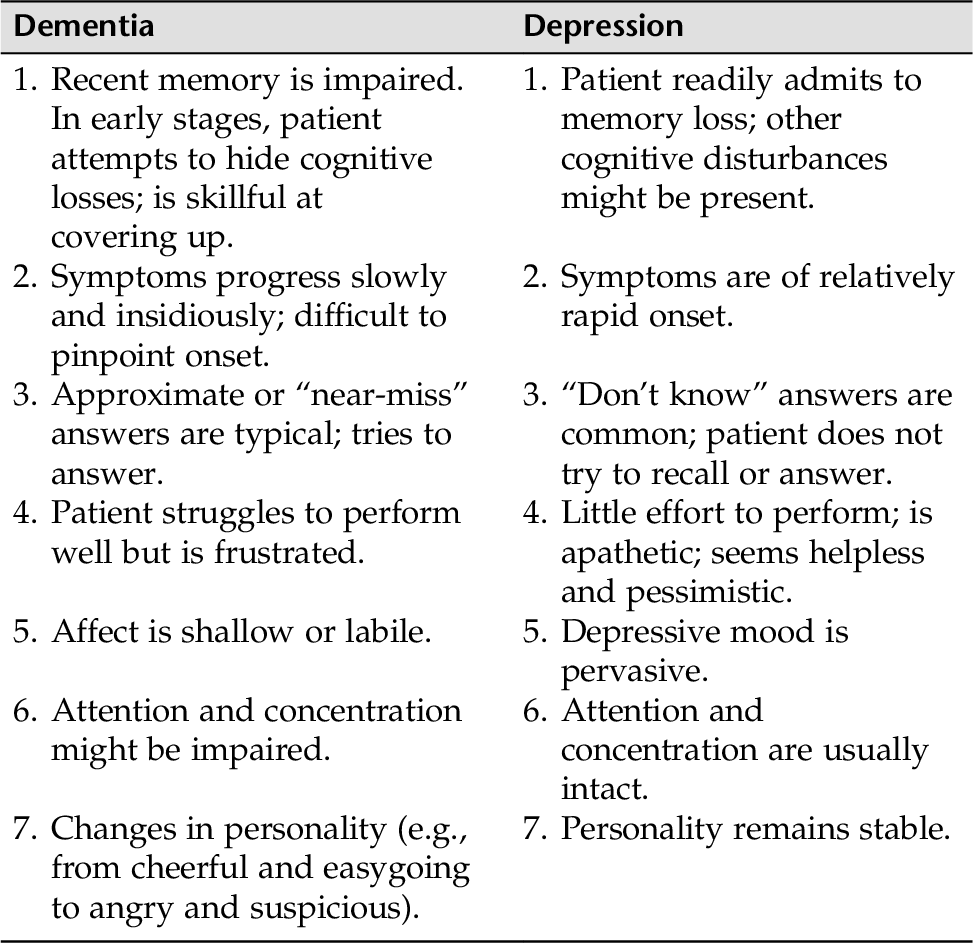

CHAPTER 13 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) identifies three neurocognitive syndromes: Major Neurocognitive Syndrome (dementia), Minor Neurocognitive syndrome (delirium), and Mild Neurocognitive Disorder. Cognition is the operation of the mind that includes “the mental faculty of knowing, perceiving, recognizing, conceiving, judging, reasoning, and imagining” (American Heritage Medical Dictionary, 2007). Cognition includes the ability to understand and process information, focus attention, solve problems and reliable source of memory function. Neurocognitive disorders affect the brain’s ability to function and interfere with a person’s intellect, emotional stability, social ability, and certainly occupational functioning. For our purposes, we will discuss two main categories of the cognitive/neurocognitive disorders: delirium and dementia. Delirium is a syndrome that is associated with minor neurocognitive disorders. It is characterized by a mental state of confusion, which comes on suddenly and fluctuates in intensity. Delirium can have multiple causes but is always secondary to another condition, such as a general medical condition (i.e., infections, diabetes), or may be substance induced (drugs, medications, or toxins). Delirium is usually a transitory condition and reversed when interventions are timely. Prolonged delirium can lead to dementia. Dementia is a syndrome associated with a major neurocognitive disorder. Dementia develops more slowly and is characterized by multiple cognitive deficits that include impairment in short-term and long-term memory. Dementia is usually irreversible. Dementia can be primary or secondary to another condition. Table 13-1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the characteristics of delirium and dementia. Table 13-1 Nursing Assessment: Delirium versus Dementia Varcarolis, E. (2012). Essentials of psychiatric mental health nursing (2nd ed.). St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders, p. 334. In a Mild Neurocognitive Disorder people have mild cognitive impairments (MCI), but this category excludes people with dementia and age-associated memory impairment. The impairment primarily involves a mild cognitive decline. Cognitive declines according to the DSM-5”may present in one or more difficulties with complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual motor, or social cognition” (APA, 2013,p.605). A person with Mild Cognitive Disorder is still able to maintain independence in their living, working, and social lives, although not up to their optimum level and with the aid of compensatory mechanisms and with greater effort. Delirium is a syndrome, and is always secondary to a medical disorder or toxicity, it is often seen on medical and surgical units. Delirium is often experienced by older adults, children with a high fever, postoperative patients, and patients with cerebrovascular disease and congestive heart failure. Delirium can occur in people with infections, metabolic disorders, drug intoxications and withdrawals, medication toxicity, neurological diseases, tumors, and certain psychosocial stressors. Delirium is important to recognize because if it continues without intervention, irreversible brain damage can occur. • Impaired ability to reason and carry out goal-directed behavior • Alternating patterns of hyperactivity to hypoactivity (slow down activity to stupor or coma) • Behaviors seen when hyperactive include: • Restlessness • Incoherent, loud, or rapid speech • Irritability • Anger and/or combativeness • Profanity • Euphoria • Distractibility • Tangentiality • Nightmares • Persistent abnormal thoughts (delusions) • Behaviors seen when hypoactive include: • Speaks and moves little or slowly • Has spells of staring • Reduced alertness • Generalized loss of awareness of the environment • Impaired attention span • Cognitive changes not accounted for by dementia: • Memory impairment • Disorientation to time and place • Language disturbance; might be incoherent • Perceptual disturbance (hallucinations and illusions) • Alterations in sleep/wake cycles • Fear and high levels of anxiety When assessing individuals with confusional states, it is helpful to use structured cognitive screening tests such as the Neurocognitive Mental Status Exam. (The latter may be found in Appendix D-9A.) 1. Assess for fluctuating levels of consciousness, which is key in delirium. 2. Interview family or other caregivers. 3. Assess for past confusional states (e.g., prior dementia diagnosis). 4. Identify other disturbances in medical status (e.g., dyspnea, edema, presence of jaundice). 5. Identify any electroencephalogram (EEG), neuroimaging, or laboratory abnormalities in patient’s record. 6. Assess vital signs, level of consciousness, and neurological signs. 7. Ask the patient (when lucid) or family what they think could be responsible for the delirium (e.g., medications, withdrawal of substance, other medical condition). 8. Assess potential for injury (is the patient safe from falls, wandering). 9. Assess need for comfort measures (pain, cold, positioning). 10. Are immediate medical interventions available to help prevent irreversible brain damage? Individuals experiencing delirium often misinterpret environmental cues (illusions) or imagine they see things (hallucinations) that they most likely believe are threatening or harmful. When patients act on these interpretations of their environment, they are likely to demonstrate a Risk for Injury. The symptoms of confusion usually fluctuate, and nighttime is the most severe (this is often called sundowning). Therefore, these patients often have Disturbed Sleep Pattern. During times of severe confusion, individuals are usually terrified and cannot care for their needs or interact appropriately with others, so Fear, Self-Care Deficit, and Impaired Social Interaction are also potential diagnoses. This section on delirium concerns Acute Confusion, which covers many of the problems mentioned. Please note that many of the interventions, especially those for communication with the patient with delirium when confused, are also applicable to the patient with dementia when confused. Table 13-2 identifies potential nursing diagnoses that are useful for the confused patient (delirium or dementia). 2. When patients are confused and frightened and are having a difficult time interpreting reality, they might be prone to accidents. Therefore, safety is a high priority. 3. Delirium is a terrifying experience for many patients. When some individuals recover to their premorbid cognitive function, they are left with frightening memories and images. Some clinicians advocate preventive counseling and education after recovery from acute brain failure. 4. Refrain from using restraints. Encourage one or two significant others to stay with the patient to provide orientation and comfort. • Oriented to time, place, and person • Resume usual cognitive and physical activities • Absence of untoward effects from episode of delirium • Patient will correctly state time, place, and person within a few days • Patient will remain free from injury (e.g., falls) throughout periods of confusion • Patient and others will remain safe during patient’s periods of agitation or aggressive behaviors. • Patient will respond positively to staff efforts to orient him or her to time, place, and person throughout periods of confusion. • Patient will take medication as offered to help alleviate the condition. Dementia is a syndrome that is marked by progressive deterioration in intellectual function, memory, and ability to solve problems and learn new skills. Judgment and moral and ethical behaviors decline as personality is altered. Unlike delirium, dementia can be of a primary nature and is usually not reversible. Dementia is usually a slow and insidious process progressing over months or years. Dementia affects memory and ability to learn new information or to recall previously learned information. Dementia also compromises intellectual functioning and the ability to solve problems. Common causes of dementia are: • Vascular dementia (multi-infarct) • HIV • Head trauma • Parkinson’s disease • Huntington’s disease • Pick’s disease • Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease • General medical conditions (e.g., brain tumors, subdural hematoma) • Substance use However, the most prevalent primary dementia is dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT). The second most common form of dementia is vascular dementia, which is caused by multiple strokes. As mentioned above, substances can effect memory and also lead to dementia (e.g., alcohol, inhalants, phencyclidine, piperidine, and a host of other drugs both legal and illegal), as can other medical conditions. The DSM-5 also allows the degree of impairment to give the diagnoses of a major Neurocognitive disorder. For example for Alzheimer’s disease, the diagnoses might be “Major space or Mild Neurocognitive Disorder To to Alzheimer’s Disease” • Clear evidence of memory impairment, usually short-term memory first • Progressive decline in cognitive functions, both predominantly with Alzheimer’s: Aphasia: language disturbance, difficulty finding words, using words incorrectly Apraxia: inability to carry out motor activities despite motor functions being intact (e.g., putting on clothes) Agnosia: loss of sensory ability; inability to recognize or identify familiar objects (e.g., a toothbrush) or sounds (e.g., telephone ringing); loss of ability to problem solve, plan, organize, or abstract • Significant gradual decline in previous level of functioning; poor judgment • Mood disturbances, anxiety, hallucinations, delusions, and impaired sleep A variety of other medical problems can masquerade as dementia. For example, depression in older adults is often misdiagnosed as dementia. Table 13-3 highlights the difference between dementia and depression and can be a useful guide for assessment.

Neurocognitive Disorders

OVERVIEW

Minor Neurocognitive Disorders

Major Neurocognitive Disorder

Delirium

Dementia

Onset

Acute impairment of orientation, memory, intellectual function, judgment, and affect

Slow, insidious deterioration in cognitive functioning

Essential feature

Disturbance in consciousness, fluctuating levels of consciousness, and cognitive impairment

Progressive deterioration in memory, orientation, calculation, and judgment; symptoms do not fluctuate

Cause

The syndrome is secondary to many underlying disorders that cause temporary, diffuse disturbances of brain function.

The syndrome is either primary in etiology or secondary to other disease states or conditions

Course

The clinical course is usually brief (hours to days); prolonged delirium may lead to dementia.

Progresses over months or years; often irreversible

Speech

May be slurred; reflects disorganized thinking

Generally normal in early stages; progressive aphasia; confabulation

Memory

Short-term memory impaired

Short-term, then long-term, memory destroyed

Perception

Visual or tactile hallucinations; illusions

Hallucinations not prominent

Mood

Fear, anxiety, and irritability most prominent

Mood labile; previous personality traits become accentuated (e.g., paranoid, depressed, withdrawn, and obsessive-compulsive)

Electroencephalogram

Pronounced, diffuse slowing or fast cycles.

Mild Neurocognitive Disorder

Minor Neurocognitive Impairment: Delirium

ASSESSMENT

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Assessment Tools

Assessment Guidelines

Delirium

NURSING DIAGNOSES WITH INTERVENTIONS

Discussion of Potential Nursing Diagnoses

Overall Guidelines for Nursing Interventions

Delirium

Selected Nursing Diagnoses and Nursing Care Plans

Some Related Factors (Related To)

Metabolic disorder, neurological disorder, chemicals, medications, infections, fluid and electrolyte imbalances

Metabolic disorder, neurological disorder, chemicals, medications, infections, fluid and electrolyte imbalances

Defining Characteristics (As Evidenced By)

Fluctuation in sleep/wake cycle

Fluctuation in sleep/wake cycle

Fluctuation in level of consciousness

Fluctuation in level of consciousness

Misperceptions of the environment (e.g., illusions, hallucinations)

Misperceptions of the environment (e.g., illusions, hallucinations)

Lack of motivation to initiate and/or follow through with goal-directed or purposeful behavior

Lack of motivation to initiate and/or follow through with goal-directed or purposeful behavior

Outcome Criteria

Long-Term Goals

Short-Term Goals

INTERVENTIONS AND RATIONALES

Major Cognitive Disorder: Dementia

ASSESSMENT

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Assessment Tools

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree