Cultural Diversity and Community Health Nursing

Carrie L. Abele*

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Critically analyze racial and cultural diversity in the United States.

4. Apply the principles of transcultural nursing to community health nursing practice.

Key Terms

biomedical

cultural imposition

cultural negotiation

cultural stereotyping

culture

culture shock

culture specific

culture universal

culture-bound syndrome

culturological assessment

dominant value orientation

ethnocentrism

Leininger’s theory of culture care diversity and universality

magicoreligious

naturalistic

norms

poverty

religion

socioeconomic status (SES)

spirituality

subculture

transcultural nursing

value

yin-yang theory

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Cultural diversity

Cultural diversity is a multifaceted and complex concept that refers to the differences among people, especially those related to values, attitudes, beliefs, norms, behaviors, customs, and ways of living. It is essential that all nurses understand how cultural groups view life processes, how cultural groups define health and illness, how healers cure and care for members of their respective cultural groups, and how the cultural background of the nurse influences the way in which care is delivered. Nurses in community health settings also need to understand the diversity or differences that occur in families, groups, neighborhoods, communities, and public and community health care organizations.

Transcultural perspectives on community health nursing

Nurses’ knowledge of culture and cultural concepts improves the health of the community by enhancing their ability to provide culturally competent care. Culturally competent community health nursing requires that nurses understand the lifestyle, value system, and health and illness behaviors of diverse individuals, families, groups, and communities. Nurses also should understand the culture of institutions that influence the health and well-being of communities. Nurses who have knowledge of, and an ability to work with, diverse cultures are able to devise effective interventions to reduce risks in a manner that is culturally congruent with community, group, and individual values.

In the United States, metaphors such as melting pot, mosaic, and salad bowl describe the cultural diversity that characterizes the population. Although there is a tendency to identify the federally defined racial and ethnic minority groups when referring to the cultural aspects of community health nursing, all individuals, families, groups, communities, and institutions, including nurses and the nursing profession, have cultural characteristics that influence community health. When planning and implementing health care, community health nurses need to balance cultural diversity with the universal human experience and common needs of all people.

Population trends

The population of the United States is becoming increasingly diverse. In recent years, the populations within the federally defined minority groups have grown faster than the population as a whole. In 1970, minority groups accounted for 16% of the population. By 1999, this share increased to 30%. Assuming that current trends continue, the U.S. Census Bureau (2009) projects that, by 2025, more than half of all children will be minorities and that, by 2050 minorities will account for 54% of the total population. For the first time in U.S. history, minorities will make up a majority of the total population.

Furthermore, the numbers of certain minority groups, such as Hispanics, are growing considerably faster than those of whites and other groups. If current demographic trends continue, the United States will have the following population composition by the year 2050: white, 44%; Hispanic, 30%; black, 15%; Asian, 9%; and American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009).

Although the nursing profession has representatives from diverse groups, minorities are generally underrepresented. Currently about 81.8% of registered nurses (RNs) in the United States are white/non-Hispanic. Estimates for each minority group are as follows: black, 4.2%; Hispanic, 1.7%; Asian and Pacific Islander, 3.1%; and Native American and Alaska Native, 0.3% (Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], 2009). Additionally, each minority group is distributed differently around the country. Black nurses are more likely to be found in the South, Hispanics in the West or South (i.e., especially states bordering Mexico), and Asian and Pacific Islanders in the West or Northeast. Native American and Alaska Native nurses are predominantly in states with reservations.

The United States has grown and achieved its success largely through immigration. Since 1991, more than 13 million legal immigrants have come to United States (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2006). In 2003, the U.S. population included 33.5 million foreign-born individuals, or 11.7% of the total population. Among those foreign born, 53.3% were born in Latin America, 25% in Asia, 13.7% in Europe, and the remaining 8% in other regions of the world (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004). The number of immigrants and refugees in the United States is projected to continue to increase.

In addition, people from other countries will continue to seek treatment in U.S. hospitals, particularly for cardiovascular, neurological, and cancer care, and U.S. nurses will have the opportunity to travel abroad to work in a variety of health care settings in the international marketplace. In the course of a nursing career, it is possible to encounter foreign visitors, international university faculty members, international high school and university students, family members of foreign diplomats, immigrants, refugees, as well as members of more than 130 different ethnic groups, and Native Americans from more than 557 federally recognized tribes. A serious conceptual problem exists within nursing in that nurses are expected to know, understand, and meet the health needs of these culturally diverse individuals, groups, and communities.

Members of some cultural groups desire culturally relevant health care that incorporates their specific beliefs and practices. An increasing expectation exists among members of certain cultural groups that health care providers will respect their “cultural health rights,” an expectation that frequently conflicts with the unicultural, Western biomedical worldview taught in most U.S. educational programs that prepare nurses and other health care providers.

Given the multicultural composition of the United States and the projected increase in the number of individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds, concern for cultural beliefs and practices of people in community health nursing is becoming increasingly important. Nursing is inherently a transcultural phenomenon, in that the context and process of helping people involves at least two people who often have different cultural orientations or intracultural lifestyles.

Cultural perspectives and healthy people 2020

Healthy People 2020, the new proposed prevention agenda for the nation, identifies priority areas and objectives. By developing a set of national health targets, which includes eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in health, U.S. health officials, together with state and local officials and members of the private sector, set goals to increase the quality and years of healthy life for all Americans (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2009).

The Healthy People 2020 proposed objectives embrace and focus on ways to close the gaps in health outcomes. Particularly targeted are racial and ethnic disparities in areas including diabetes, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), heart disease, infant mortality rates, cancer screening and management, and immunizations. The objectives bring focus on disparities among racial and ethnic minorities, women, youth, older adults, people of low income and education, and people with disabilities (USDHHS, 2000). The Healthy People 2020 box lists selected objectives from Healthy People 2020 specific to cultural health issues.

The aims of Healthy People 2020 are the promotion of healthy behaviors, promotion of healthy and safe communities, improvement of systems for personal and public health, and prevention and reduction of diseases and disorders. The initiative is a tool for monitoring and tracking health status, health risks, and use of health services.

Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care

As in many nations, people in the United States who come from various racial, ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds often experience marked disparities in health care. The occurrence of many diseases, injuries, and other public health problems is disproportionately higher in some groups; access to health care may be more restricted, and the overall quality of health care is deemed inferior, for people from certain racial, ethnic, and cultural populations. Although the overall health of the U.S. population has improved during the past several decades, research reveals that all people have not shared equally in those improvements. For example, 17% of Hispanic adults and 16% of black adults report that they are in fair or poor health, compared with 10% of non-Hispanic whites (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005).

Primary care provides the foundation for the health care system, and research indicates that having a usual source of care increases the chance that people will receive adequate preventive care and other important health services. Data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2005) reveal the following facts:

During the past two decades, health disparities have become the focus of numerous federal, state, and local government studies, and one of the major goals of Healthy People 2020 is to achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups (USDHHS, 2009). Therefore, it is essential to look at how to overcome these and other identified factors that contribute to poorer health among members of some minority groups. A recent study by the Commonwealth Fund (2007) found that disparities in health care can be reduced or even eliminated when adults have health care insurance and a medical home, which is defined as “a health care setting that provides patients with timely, well-organized care and enhanced access to providers.” According to the survey, when adults have insurance and a medical home, “their access to needed care, receipt of routine preventive screenings, and management of chronic conditions improve substantially.”

Transcultural nursing

In 1959, Madeleine Leininger, a nurse-anthropologist, used the term transcultural nursing to define the philosophical and theoretical similarities between nursing and anthropology. In 1968, Leininger proposed her theory-generated model, and, in 1970, she wrote the first book on transcultural nursing, Nursing and Anthropology: Two Worlds to Blend (Leininger, 1970). According to Leininger (1978), transcultural nursing is “a formal area of study and practice focused on a comparative analysis of different cultures and subcultures in the world with respect to cultural care, health and illness beliefs, values, and practices with the goal of using this knowledge to provide culture-specific and culture-universal nursing care to people” (p. 493). Culture specific refers to the “particularistic values, beliefs, and patterning of behavior that tend to be special, ‘local,’ or unique to a designated culture and which do not tend to be shared with members of other cultures” (Leininger, 1991, p. 491), whereas culture universal refers to the “commonalties of values, norms of behavior, and life patterns that are similarly held among cultures about human behavior and lifestyles and form the bases for formulating theories for developing cross-cultural laws of human behavior” (Leininger, 1991, p. 491).

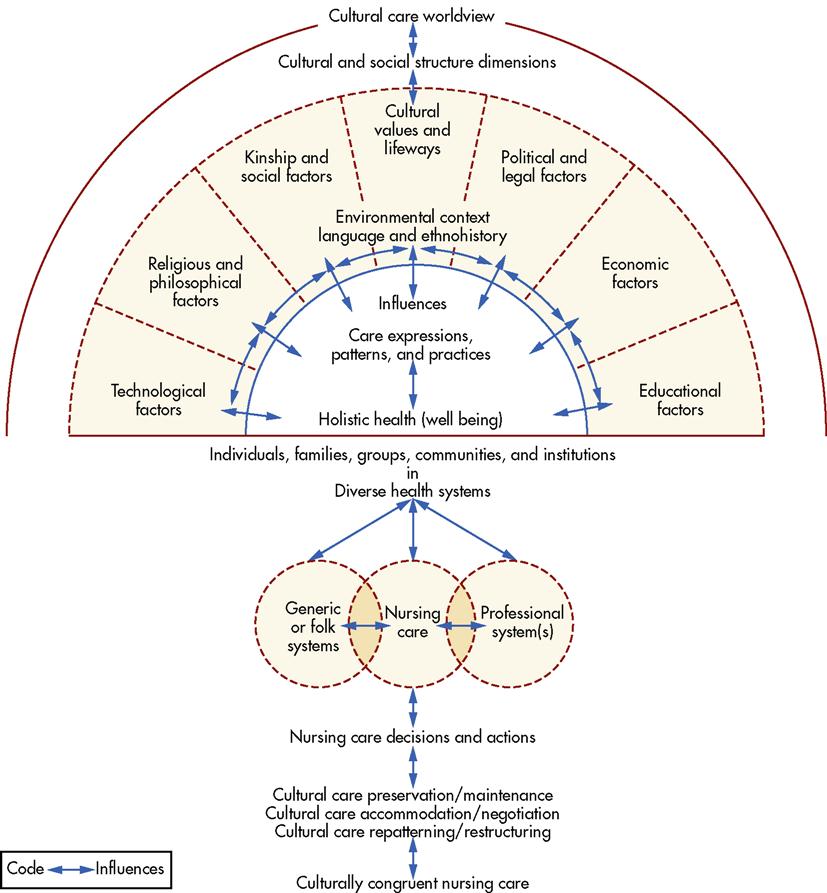

Although many nurse-scholars have developed theories of nursing, Leininger’s theory of culture care diversity and universality is the only one that gives precedence to understanding the cultural dimensions of human care and caring. Leininger’s theory is concerned with describing, explaining, and projecting nursing similarities and differences focused primarily on human care and caring in human cultures. Leininger used worldview, social structure, language, ethnohistory, environmental context, and the generic or folk and professional systems to provide a comprehensive and holistic view of influences in cultural care and well-being. The following three models of nursing decisions and actions may be useful in providing culturally congruent and competent care (Andrews and Boyle, 2008; Leininger, 1978, 1991, 1995; Leininger and McFarland, 2002):

Among the strengths of Leininger’s theory is its flexibility for use with individuals, families, groups, communities, and institutions in diverse health systems. Leininger’s Sunrise Model (Figure 13-1) depicts the theory of cultural care diversity and universality and provides a visual representation of the key components of the theory and the interrelationships among its components.

The term cross-cultural nursing is sometimes used synonymously with transcultural nursing. The terms intercultural nursing and multicultural nursing and the phrase “ethnic people of color” are also used. Since Leininger’s early work, many nurses have contributed significantly to the advancement of nursing care of culturally diverse clients, groups, and communities, and some of their contributions are mentioned in this chapter.

One of the major challenges that community health nurses face in working with clients from culturally diverse backgrounds is overcoming individual ethnocentrism, which is a person’s tendency to view his or her own way of life as the most desirable, acceptable, or best and tendency to act in a superior manner toward individuals from another culture. Nurses also must beware of cultural imposition, which is a person’s tendency to impose his or her own beliefs, values, and patterns of behavior on individuals from another culture. When clients’ cultural values and expressions of care differ from those of the nurse, the nurse must exercise caution to ensure that mutual goals have been established.

Overview of culture

In 1871, the English anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor was the first to define the term culture. According to Tylor (1871), culture refers to the complex whole, including knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, law, customs, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by virtue of the fact that one is a member of a particular society. Culture represents a person’s way of perceiving, evaluating, and behaving within his or her world, and it provides the blueprint for determining his or her values, beliefs, and practices. Culture has four basic characteristics:

1. It is learned from birth through the processes of language acquisition and socialization.

2. It is shared by members of the same cultural group.

Culture is an all-pervasive and universal phenomenon. However, the culture that develops in any given society is always specific and distinctive, encompassing the knowledge, beliefs, customs, and skills acquired by members of that society. Within cultures, groups of individuals share beliefs, values, and attitudes that are different from those of other groups within the same culture. Ethnicity, religion, education, occupation, age, sex, and individual preferences and variations bring differences. When such groups function within a large culture, they are termed subcultural groups.

The term subculture is used for fairly large aggregates of people who share characteristics that are not common to all members of the culture and that enable them to be a distinguishable subgroup. Ethnicity, religion, occupation, health-related characteristics, age, sex, and geographic location are frequently used to identify subcultural groups. Examples of U.S. subcultures based on ethnicity (e.g., subcultures with common traits such as physical characteristics, language, or ancestry) include blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Chinese Americans. Subcultures based on religion include members of the more than 1200 recognized religions, such as Catholics, Jews, Mormons, Muslims, and Buddhists. Those based on occupation include health care professionals (e.g., nurses and physicians), career military personnel, and farmers. Those based on health-related characteristics include the blind, hearing impaired, and mentally challenged. Subcultures based on age include adolescents and older adults, and those based on sex or sexual preference include women, men, lesbians, and gay men. Those based on geographic location include Appalachians, Southerners, and New Yorkers.

Culture and the Formation of Values

According to Leininger (1995), value refers to a desirable or undesirable state of affairs. Values are a universal feature of all cultures, although the types and expressions of values differ widely. Norms are the rules by which human behavior is governed and result from the cultural values held by the group. All societies have rules or norms that specify appropriate and inappropriate behavior. Individuals are rewarded or punished as they conform to, or deviate from, the established norms. Values and norms, along with the acceptable and unacceptable behaviors associated with them, are learned in childhood.

Every society has a dominant value orientation, a basic value orientation that is shared by the majority of its members as a result of early common experiences. In the United States, the dominant value orientation is reflected in the dominant cultural group, which is made up of white, middle-class Protestants, typically those who came to the United States at least two generations ago from northern Europe. Many members of the dominant cultural group are of Anglo-Saxon descent; thus, they are sometimes referred to as white Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs). In the United States, the dominant cultural group places emphasis on educational achievement, science, technology, individual expression, democracy, experimentation, and informality.

Although an assumption is sometimes made that the term white refers to a homogeneous group of Americans, a rich diversity of ethnic variation exists among the many groups that constitute the dominant majority. Countries of origin include those of eastern and western Europe (e.g., Ireland, Poland, Italy, France, Sweden, and Russia). The origins of people in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa can ultimately be traced to western Europe. Appalachians, the Amish, Cajuns, and other subgroups are also examples of whites who have cultural roots that are recognizably different from those of the dominant cultural group.

Values and norms vary, sometimes significantly, among various cultural groups. According to Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961), several basic human problems exist for which all people must find a solution. They identified the following five common human problems related to values and norms:

1. What is the character of innate human nature (human nature orientation)?

2. What is the relationship of the human to nature (person-nature orientation)?

3. What is the temporal focus (i.e., time sense) of human life (time orientation)?

4. What is the mode of human activity (activity orientation)?

5. What is the mode of human relationships (social orientation)?

Human Nature Orientation

Innate human nature may be good, evil, or a combination of good and evil. Some believe that life is a struggle to overcome a basically evil nature; they consider human nature to be unalterable or able to be perfected only through great discipline and effort. For others, human nature is perceived as fundamentally good, unalterable, and difficult or impossible to corrupt.

According to Kohls (1984), the dominant U.S. cultural group chooses to believe the best about a person until that person proves otherwise. Concern in the United States for prison reform, social rehabilitation, and the plight of less fortunate people around the world is a reflective perception of the belief in the fundamental goodness of human nature. Recent scientific advances, such as the advent of stem cell research and genome studies, have necessitated consideration of ethical quandaries regarding human nature. Questions emerge as to whether science can or should pursue activities that could alter the basic human orientation.

Person-Nature Orientation

The following three perspectives examine the ways in which the person-nature relationship is perceived:

1. Destiny, in which people are subjugated to nature in a fatalistic, inevitable manner

2. Harmony, in which people and nature exist together as a single entity

Most Americans consider humans and nature clearly separated; this is an incomprehensible perspective for many individuals of Asian heritage. The idea that a person can control his or her own destiny is alien to many individuals of culturally diverse backgrounds. Many cultures believe that people are driven and controlled by fate and can do very little, if anything, to influence it. Americans, by contrast, have an insatiable drive to subdue, dominate, and control their natural environment.

For example, the reader should consider three individuals in whom hypertension has been diagnosed, where each embraces one of the values orientations described. The person whose values orientation is destiny may say, “Why should I bother watching my diet, taking medication, and getting regular blood pressure checks? High blood pressure is part of my genetic destiny and there is nothing I can do to change the outcome. There is no need to waste money on prescription drugs and health checkups.” The person whose values orientation embraces harmony may say, “If I follow the diet described and use medication to lower my blood pressure, I can restore the balance and harmony that were upset by this illness. The emotional stress I’ve been feeling indicates an inner lack of harmony that needs to be balanced.” The person whose values orientation leads to belief in active mastery may say, “I will overcome this hypertension no matter what. By eating the right foods, working toward stress reduction, and conquering the disease with medication, I will take charge of the situation and influence the course of my disease.”

Time Orientation

People can perceive time in the following three ways:

The dominant U.S. cultural group is characterized by a belief in progress and a future orientation. This implies a strong task or goal focus. This group has an optimistic faith in what the future will bring. Change is often equated with improvement, and a rapid rate of change is usually normal.

Activity Orientation

This values orientation concerns activity. Philosophers have suggested the following three perspectives:

The person often directs the doing toward achievement of an externally applied standard, such as a code of behavior from a religious or ethical perspective. The Ten Commandments, Pillars of Islam, Hippocratic oath, and Nightingale pledge are examples of externally applied standards.

The dominant cultural value is action oriented, with an emphasis on productivity and being busy. As a result of this action orientation, Americans have become proficient at problem solving and decision making. Even during leisure time and vacations, many Americans value activity.

Social Orientation

Variations in cultural values orientation are also related to the relationships that exist with others. Relationships may be categorized in the following three ways:

The social orientation among the dominant U.S. cultural group is toward the importance of the individual and the equality of all people. Friendly, informal, outgoing, and extroverted members of the dominant cultural group tend to scorn rank and authority. For example, nursing students may call faculty members by their first names, clients may call nurses by their first names, and employees may fraternize with their employers.

Members of the dominant culture have a strong sense of individuality. However, family ties are relatively weak, as demonstrated by the high rate of separation and divorce in the United States, as well as the frequently widespread geographic separation of extended families. In many U.S. households, the family has been reduced to its smallest unit: the single-parent family.

When making health-related decisions, clients from culturally diverse backgrounds rely on relationships with others in various ways. If the cultural values orientation is lineal, the client may seek assistance from other members of the family and allow a relative (e.g., parent, grandparent, or elder brother) to make decisions about important health-related matters. If collateral relationships are valued, decisions about the client may be interrelated with the influence of illness on the entire family or group. For example, among the Amish, the entire community is affected by the illness of a member because the community pays for health care from a common fund. Members join together to meet the needs of the client and family for the duration of the illness, and the roles of many in the community are likely to be affected by the illness of a single member.

In another example, there are approximately 10.3 million undocumented residents living in the United States (Passel, 2005). These individuals often create their own social groups in which they seek to protect themselves from being discovered by immigration authorities. These groups fear that attempting to access the health care system may lead to deportation, and they often have “underground” or private access to home remedies and pharmaceuticals for their health care. As a result, they often enter the formal health care system via emergency departments when their health status has declined considerably.

A values orientation that emphasizes the individual is predominant among the dominant cultural majority in the United States. Decision making about health and illness is often an individual matter, with the client being responsible, although members of the nuclear family may participate to varying degrees.

Culture and the Family

The family remains the basic social unit in the United States. Although various ways exist to categorize families, the following are commonly recognized types of constellations in which people live together in society:

• Nuclear (i.e., husband, wife, and child or children)

• Nuclear dyad (i.e., husband and wife alone, either childless or with no children living at home)

• Single parent (i.e., either mother or father and at least one child)

• Blended (i.e., husband, wife, and children from previous relationships)

• Extended (i.e., nuclear plus other blood relatives)

• Communal (i.e., group of men and women with or without children)

• Cohabitation (i.e., unmarried man and woman sharing a household with or without children)

In addition to structural differences in families cross-culturally, accompanying functional diversity may exist. For example, among extended families, kin residence sharing has long been recognized as a viable alternative to managing scarce resources, meeting child care needs, and caring for a handicapped or older family member. Sometimes the shared household is an adaptation for survival and protection. In general, families with a culturally diverse heritage include a large number of adults and a larger number of children.

The family constellations associated with teen parenting are unique and provide a special socialization context for infants. For example, Hispanic teen mothers receive more child care help from grandmothers and peers than do white teen mothers. Among blacks and Puerto Ricans, the presence of the maternal grandmother ameliorates the negative consequences of adolescent childbirth on the infant. In addition, grandmothers are more responsive and less punitive in their interactions with the infant than their daughters (Andrews and Boyle, 2008). Three-generational households can have an influence on the infant’s development: by influencing the mother’s knowledge about development and providing other more responsive social interactions with infants.

Families from diverse backgrounds are often characterized as being more conservative in terms of sex roles and parenting values and practices than white families. For example, traditional Japanese-American and Mexican-American families are family centered, enforce strict gender and age roles, and emphasize children’s compliance with authority figures. Children of culturally diverse backgrounds are involved in family interactions that differ from those of children from the dominant U.S. cultural group. The values of children of immigrants typically evolve, depending on how far removed they are from the country of origin. These children may detach from their cultural traditions, becoming more individually focused or autonomous—often to the dismay of the elders in the family. Often the language of the ancestors is forgotten, or in certain subcultures, forbidden to be spoken, so that the children may assimilate to the dominant culture.

Relationships that may seem apparent sometimes warrant further exploration by nurses interacting with clients from culturally diverse backgrounds. For example, the dominant cultural group defines siblings as two people with the same mother, the same father, the same mother and father, or the same adoptive parents. In some Asian cultures, a sibling relationship is defined as involving infants who are breastfed by the same woman. In other cultures, certain kinship patterns, such as maternal first cousins, are sibling relationships. In some African cultures, anyone from the same village or town may be called “brother” or “sister.”

Certain subcultures, such as Roman Catholics, who may be further subdivided by ethnicity into those who are Italian, Polish, Spanish, Mexican, and so on, recognize relationships such as “godmother” and “godfather.” The godmother/godfather is an individual who is not the biological parent but promises to assist with the moral and spiritual development of an infant and agrees to care for the child in the event of parental death. The godparent makes these promises during the religious ceremony of baptism.

When providing care for infants and children, the nurse must identify the primary provider of care because this individual may or may not be the biological parent. For example, among some Hispanic groups, female members of the nuclear or extended family (e.g., sisters or aunts) are sometimes the primary providers of care. In some black families, the grandmother may be the decision maker and primary caregiver of the children.

Culture and socioeconomic factors

No single indicator can adequately capture all facets of economic status for entire populations, but measures such as median or average annual income, employment rate, poverty rate, and net worth are most often used. The economic status of most individuals, especially children, is better reflected by the pooled resources of family or household members than by their individual earnings or incomes. Socioeconomic status (SES) is a composite of the economic status of a family or unrelated individuals based on income, wealth, occupation, educational attainment, and power. It is a means of measuring inequalities based on economic differences and the manner in which families live as a result of their economic well-being. Most families with racially or ethnically diverse backgrounds have a lower SES than the population at large, with a few exceptions (e.g., Cuban Americans and subgroups of Asian Americans).

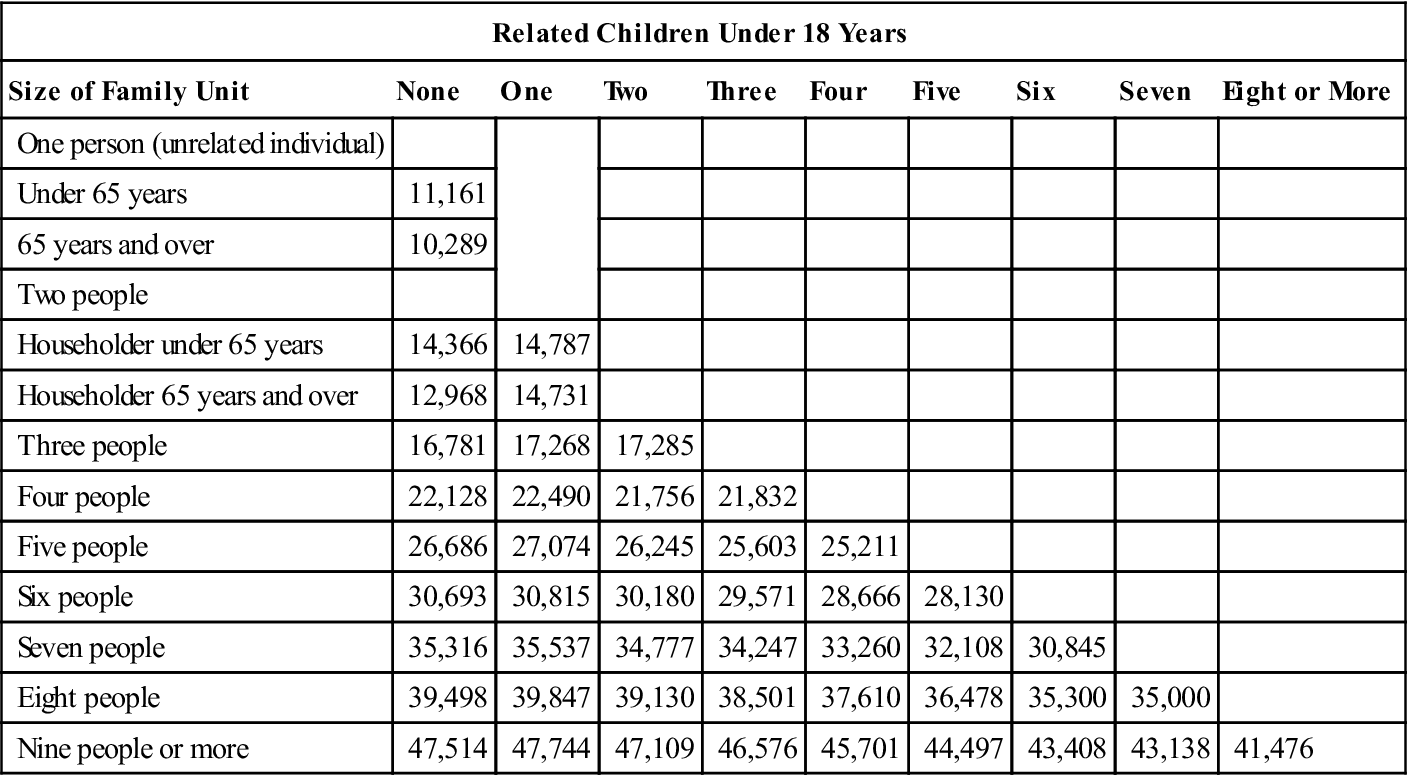

Poverty is another factor that dramatically influences health and well-being. National poverty data are calculated using the official U.S. Census Bureau definition of poverty, which has remained standard since its initial introduction in the mid-1960s. Under this definition, poverty is determined by comparing pretax cash income with the poverty threshold, which adjusts for family size and composition. Table 13-1 provides an overview of the poverty thresholds according to size of family and number of related children under age 18 years residing in the home. The poverty guidelines are issued each year by the USDHHS. The guidelines are a simplification of the poverty threshold for administrative purposes, such as determining financial eligibility for federal programs (e.g., Head Start, National School Lunch, Medicaid, Aid to Families with Dependent Children) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2007).

TABLE 13-1

Poverty Thresholds for 2009 by Size of Family and Number of Related Children Under 18 Years

| Related Children Under 18 Years | |||||||||

| Size of Family Unit | None | One | Two | Three | Four | Five | Six | Seven | Eight or More |

| One person (unrelated individual) | |||||||||

| Under 65 years | 11,161 | ||||||||

| 65 years and over | 10,289 | ||||||||

| Two people | |||||||||

| Householder under 65 years | 14,366 | 14,787 | |||||||

| Householder 65 years and over | 12,968 | 14,731 | |||||||

| Three people | 16,781 | 17,268 | 17,285 | ||||||

| Four people | 22,128 | 22,490 | 21,756 | 21,832 | |||||

| Five people | 26,686 | 27,074 | 26,245 | 25,603 | 25,211 | ||||

| Six people | 30,693 | 30,815 | 30,180 | 29,571 | 28,666 | 28,130 | |||

| Seven people | 35,316 | 35,537 | 34,777 | 34,247 | 33,260 | 32,108 | 30,845 | ||

| Eight people | 39,498 | 39,847 | 39,130 | 38,501 | 37,610 | 36,478 | 35,300 | 35,000 | |

| Nine people or more | 47,514 | 47,744 | 47,109 | 46,576 | 45,701 | 44,497 | 43,408 | 43,138 | 41,476 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/threshold/threshold09.html

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2008), the poverty rate in 2007 was 12.5%. The distribution of the poor varies considerably on the basis of certain factors such as age, race or ethnicity, and marital status. For example, 24.5% of the black population, 10.2% of the Asian population, and 21.5% of the Hispanic population live in poverty. In addition, children under 6 years of age are particularly vulnerable to poverty, with 20.8% of all U.S. children in this age-group being poor.

Distribution of Resources

Status, power, and wealth in the United States are not distributed equally throughout society. Rather, a small percentage of the population enjoys most of the nation’s resources, primarily through ownership of multibillion-dollar corporations, large pieces of real estate in prime locations, and similar assets. The U.S. population has traditionally been divided into the following three social classes: upper, middle, and lower. SES may be calculated by considering a variety of factors, but it is customarily determined by examining factors such as total family income, occupation, and educational level. In a less formalized examination of SES, factors such as age, sex, material possessions, health status, family name, location of residence, family composition, amount of land owned, religion, race, and ethnicity may also be considered.

A disproportionate number of individuals from the racially and ethnically diverse subgroups are members of the lower socioeconomic class, whereas a larger percentage of members of the dominant cultural group (i.e., WASPs) belong to the upper and middle socioeconomic classes. The United States has socioeconomic stratification; therefore, the idealization of America as the land of opportunity often applies more to members of the upper and middle classes than to those of the lower class. The outcome of social stratification is social inequality. For example, school systems, grocery stores, and recreational facilities vary significantly between the inner city, which has a high percentage of minority residents, and the suburbs, which are overwhelmingly WASP.

For many years, health care settings have been the subject of study and concern regarding distribution of resources, with members of racial and ethnic minority groups compellingly pointing out the inequalities. Because financing of health care in the United States largely relies on a combination of federally funded insurance (i.e., Medicare) and employer-provided health insurance, those from the highest SES and elders tend to receive the best health care. In contrast, those from low SES groups (i.e., those without health insurance or with Medicaid) tend to receive less health care. Thus, in the United States, SES largely determines acess to health care, as well as the quality of care received.

Education

One of the components considered in determining SES is educational level. Educational attainment is perhaps the single most important factor. In recent years, there has been an improvement in the level of education among those who have historically been less educated (e.g., elders, women, minorities). For example, women have a higher rate of high school completion than men. Also, dropout rates for both blacks and Hispanics are steadily declining (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2008).

Research suggests that differences between white and Mexican-American children’s home educational development can be accounted for by differences in levels of formal schooling rather than by cultural differences or economic indices. According to a study by Garcia Coll (1990), mothers who had received more years of formal education inquired and praised their children more often than did mothers with less education. In contrast, the lower the mother’s level of formal education, the more often she used modeling as a teaching strategy. Compared with white mothers, Hispanic mothers inquired and praised less often and used modeling, visual cues, directives, and negative physical control more often. However, these differences disappeared entirely when the mother’s or father’s educational level was controlled statistically. This study contributes to an understanding of the ways in which educational level attained by people from culturally diverse backgrounds affects the didactic aspects of the child-rearing environment.

Culture and nutrition

Long after assimilation into U.S. culture has occurred, many members of various ethnic groups will continue to follow culturally based dietary practices and eat ethnic foods. When a new group of immigrants arrives in the United States, neighborhood food markets and ethnic restaurants are often established soon after arrival. The ethnic restaurant is often a place for members of the cultural group to meet and mingle, and customers from the dominant cultural group may be of secondary interest. Food is an integral part of cultural identity that extends beyond dietary preferences.

Nutrition Assessment of Culturally Diverse Groups

Factors that must be considered in a nutrition assessment include the cultural definition of food, frequency and number of meals eaten away from home, form and content of ceremonial meals, amount and types of food eaten, and regularity of food consumption. Twenty-four-hour dietary recalls or 3-day food records traditionally used for assessment may be inadequate when dealing with clients from culturally diverse backgrounds. Standard dietary handbooks may fail to provide culture-specific diet information because nutritional content and exchange tables are usually based on Western diets. Another source of error may originate from the cultural patterns of eating. For example, among low-income urban black families, elaborate weekend meals are frequent, whereas weekday dietary patterns are markedly more moderate.

Although community health nurses may assume that food is a culture-universal term, they may need to clarify its meaning with the client. For example, certain Latin-American groups do not consider greens, an important source of vitamins, to be food and fail to list intake of these vegetables on daily records. Among Vietnamese refugees, dietary intake of calcium may appear inadequate because low consumption rates of dairy products are common among members of this group. However, they commonly consume pork bones and shells, providing adequate quantities of calcium to meet daily requirements.

Food is only one part of eating. In some cultures, social contacts during meals are restricted to members of the immediate or extended family. For example, in some Middle Eastern cultures, men and women eat meals separately, or women are permitted to eat with their husbands but not with other males. Among some Hispanic groups, the male breadwinner is served first, then the women and children eat. Etiquette during meals, use of hands, type of eating utensils (e.g., chopsticks or special flatware), and protocols governing the order in which food is consumed during a meal all vary cross-culturally.

Dietary Practices of Selected Cultural Groups

Cultural stereotyping is the tendency to view individuals of common cultural backgrounds similarly and according to a preconceived notion of how they behave. However, not all Chinese like rice, not all Italians like spaghetti, and not all Mexicans like tortillas. Nevertheless, aggregate dietary preferences among people from certain cultural groups can be described (e.g., characteristic ethnic dishes and methods of food preparation, including use of cooking oils); the reader is referred to nutrition texts on the topic for detailed information about culture-specific diets and the nutritional value of ethnic foods.

Religion and Diet

Cultural food preferences are often interrelated with religious dietary beliefs and practices. As indicated in Table 13-2, many religions have proscriptive dietary practices and some use food as symbols in celebrations and rituals. Knowing the client’s religious practice as it relates to food makes it possible to suggest improvements or modifications that will not conflict with religious dietary laws.

TABLE 13-2

Dietary Practices of Selected Religious Groups

| Religion | Dietary Practice |

| Hinduism | All meats are prohibited. |

| Islam | Pork and intoxicating beverages are prohibited. |

| Judaism | Pork, predatory fowl, shellfish, other water creatures (fish with scales are permissible), and blood by ingestion (e.g., blood sausage and raw meat) are prohibited. Blood by transfusion is acceptable. Foods should be kosher (meaning “properly preserved”). All animals must be ritually slaughtered by a shochet (i.e., quickly with the least pain possible) to be kosher. Mixing dairy and meat dishes at the same meal is prohibited. |

| Mormonism (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) | Alcohol, tobacco, and beverages containing caffeine (e.g., coffee, tea, colas, and select carbonated soft drinks) are prohibited. |

| Seventh-Day Adventism | Pork, certain seafood (including shellfish), and fermented beverages are prohibited. A vegetarian diet is encouraged. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020