Theris A. Touhy

Promoting healthy skin and feet

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

I can’t thank you enough for helping me with my feet. I have been to the podiatrist, but no one has made them, and me, feel so good. I feel like I can walk forever now—you are an angel.

Tom, age 86

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Identify age-related changes of the integument and feet.

• Identify skin and foot problems commonly found in late life.

• Identify preventive, maintenance, and restorative measures for skin and foot health.

Glossary

Debride To remove dead or infected tissue, usually of a wound.

Emollient An agent that softens and smoothes the skin.

Eschar Black, dry, dead tissue.

Hyperemia Redness in a part of the body caused by increased blood flow, such as in area of an infection.

Maceration Tissue that is overhydrated and subject to breakdown.

Slough Dead tissue that has become wet, appearing as yellow to white and fibrous.

Tissue tolerance The amount of pressure a tissue (skin) can endure before it breaks down, as in a pressure ulcer.

Xerosis Very dry skin.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Gerontological nurses have an instrumental role in promoting the health of the skin and the feet of the persons who seek their care. These areas of function may often be overlooked when the focus is on management of disease or acute problems. However, preservation of the integrity of the skin and the functioning of the feet is essential to well-being. In order to promote healthy aging, the nurse needs information about common problems encountered by the older adult and skill in developing effective interventions for both acute and chronic conditions.

Skin

The skin is the largest organ of the body. Exposure to heat, cold, water, trauma, friction, and pressure notwithstanding, the skin’s function is to maintain a homeostatic environment. Healthy skin is durable, pliable, and strong enough to protect the body by absorbing, reflecting, cushioning, and restricting various substances and forces that might enter and alter its function; yet it is sensitive enough to relay subtle messages to the brain. When the integument malfunctions or is overwhelmed, discomfort, disfigurement, or death may ensue. However, the nurse can both promptly recognize and help to prevent many of the sources of danger to a person’s skin in the promotion of the best possible health.

Many skin problems are seen with aging, both in health and when compromised by illness or mobility limitations. The skin problems seen in older adults are influenced by the environment and age-related changes. The most common skin problems of aging are xerosis (dry skin), pruritus, seborrheic keratosis, herpes zoster, and cancer. Those who are immobilized or medically fragile are at risk for fungal infections and pressure ulcers, both major threats to wellness.

Common skin problems

Xerosis

Xerosis is extremely dry, cracked, and itchy skin. Xerosis is the most common skin problem experienced by older people. Xerosis occurs primarily in the extremities, especially the legs, but can affect the face and the trunk as well. The thinner epidermis of older skin makes it less efficient, allowing more moisture to escape. Inadequate fluid intake worsens xerosis as the body will pull moisture from the skin in an attempt to combat systemic dehydration.

Exposure to environmental elements such as artificial heat, decreased humidity, use of harsh soaps, and frequent hot baths or hot tubs contributes to skin dryness. Nutritional deficiencies and smoking lead to dehydration of the outer layer of the epidermis. Dry skin may be just dry skin, but it may also be a symptom of more serious systemic disease (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, renal disease) or dehydration.

To prevent excessive loss of moisture and natural oil during bathing, only tepid water temperatures and super-fatted soaps or skin cleansers without hexachlorophene or alcohol should be used. Products such as Cetaphil, Basis, Dove, Tone, and Caress soaps or Jergens, Neutrogena, and Oil of Olay bath washes are effective in helping to prevent the loss of the protective lipid film from the skin surface. Most lubricants such as creams, lotions, and emollients work by trapping moisture and are most effective when applied to towel-patted, damp skin immediately after a bath. Bath oils and other hydrophobic preparations may also be used to hold in moisture. Light mineral oil is as effective and more economical than commercial brands of lotions and oils. However, oils poured directly into a tub or shower increase the risk for falls. It is safer and more effective to apply the oil directly to the moist skin. Water-laden emulsions without perfumes or alcohol are best.

Pruritus

One of the consequences of xerosis is pruritus, that is, itchy skin. It is a symptom, not a diagnosis or disease, and is a threat to skin integrity because of the attempts to relieve it by scratching. It is aggravated by perfumed detergents, fabric softeners, heat, sudden temperature changes, pressure, sweating, restrictive clothing, fatigue, exercise, and anxiety. If rehydration of the stratum corneum is not sufficient to control itching, cool compresses, or oatmeal or Epsom salt baths may be helpful. Failure to control the itching increases the risk for eczema, excoriations, cracks in the skin, inflammation, and infection. Pruritus also may accompany systemic disorders such as chronic renal failure, biliary or hepatic disease, and iron deficiency anemia. The nurse should be alert to signs of infection.

Scabies

Scabies is a skin condition that causes intense itching, particularly at night. Scabies is caused by a tiny burrowing mite called Sarcoptes scabiei. Scabies is contagious and can spread quickly through close physical contact in a family, child care group, school class, or other close communal living facilities such as nursing homes. To diagnose scabies, a close skin examination is conducted to look for signs of mites, including their characteristic burrows. A scraping may be taken from an area of skin for microscopic examination to determine the presence of mites or their eggs.

Scabies treatment involves eliminating the infestation with prescribed lotions and creams (Elimite, Lindane). Treatment is usually provided to family members, caregivers, and other close contacts even if they show no signs of scabies infestation. Medication kills the mites but itching may not stop for several weeks. The oral medication ivermectin (Stromectol) may be prescribed for individuals with altered immune systems, for those with crusted scabies, or for those who do not respond to prescription lotions and creams. All clothes and linen used at least three times before treatment should be washed in hot, soapy water and dried with high heat.

Purpura

Thinning of the dermis leads to increased fragility of the dermal capillaries and to blood vessels rupturing easily with minimal trauma. Extravasation of the blood into the surrounding tissue, commonly seen on the dorsal forearm and hands, is called purpura. These are not related to a bleeding disorder, and individuals who are prone to purpura should be advised to protect the skin against trauma and friction. Health care personnel must be advised to be gentle when handling the skin of older patients because even minor trauma can cause purpura. Long-sleeved shirts reduce shear and friction, and protect the skin against trauma. If a skin tear occurs, use nonadherent dressings secured with tubular retention bandages.

Keratoses

There are two types of keratosis: seborrheic and actinic. Actinic keratosis is a precancerous lesion and is discussed later in the chapter. Seborrheic keratosis is a benign growth that appears mainly on the trunk, the face, the neck, and the scalp as single or multiple lesions. One or more lesions are present on nearly all adults older than 65 years of age and are more common in men. An individual may have dozens of these benign lesions. Seborrheic keratosis is a waxy, raised, verrucous lesion, flesh-colored or pigmented in various sizes. The lesions have a “stuck on” appearance, as if they could be scraped off. Seborrheic keratoses may be removed by a dermatologist for cosmetic reasons. A variant seen in darkly pigmented persons occurs mostly on the face and appears as numerous small, dark, possibly taglike lesions (see www.dermatlas.com).

Herpes zoster

Herpes zoster (HZ), or shingles, is a viral infection frequently seen in older adults. HZ is caused by reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus (VZV) within the sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglion decades after initial VZV infection is established. HZ occurs most commonly in adults over 50 years of age, those who have medical conditions that compromise the immune system, or people who receive immunosuppressive drugs. HZ always occurs along a nerve pathway, or dermatome. The more dermatomes involved, the more serious the infection, especially if it involves the head. When the eye is affected it is always a medical emergency. Most HZ occurs in the thoracic region but it can also occur in the trigeminal area and cervical, lumbar, and sacral areas. HZ vesicles never cross the midline.

The onset may be preceded by itching, tingling, or pain in the affected dermatome several days before the outbreak of the rash. It is important to differentiate HZ from herpes simplex. Herpes simplex does not occur in a dermatome pattern and is recurrent. During the healing process, clusters of papulovesicles develop along a nerve pathway. The lesions themselves eventually rupture, crust over, and resolve. Scarring may result, especially if scratching or poor hygiene leads to a secondary bacterial infection. HZ is infectious until it becomes crusty. HZ may be very painful and pruritic.

Prompt treatment with the oral antiviral agents acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir decreases the severity and duration of acute pain from zoster. Zoster vaccine (Zostavax) is recommended for all persons 60 years of age and over who have no contraindications, including persons who report a previous episode of zoster or who have chronic medical conditions. Before administration of the vaccine, patients do not need to be asked about their history of varicella or have serologic testing to determine varicella immunity.

A common complication of HZ is postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), a chronic, often debilitating pain condition that can last months or even years. The risk of PHN in patients with HV is 10% to 18%. Another complication of HZ is eye involvement, which occurs in 10% to 25% of zoster episodes and can result in prolonged or permanent pain, facial scarring, and loss of vision. The pain of PHN is difficult to control and can significantly affect one’s quality of life. The American Academy of Neurology (2012) treatment guidelines for PHN include the use of tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, steroids, lidocaine skin patches, and opioids, as well as nonpharmacological treatments such as stress reduction techniques and behavioral cognitive therapy. Assessment and management of pain are discussed in Chapter 15.

Photo damage of the skin

Although exposure to sunlight is necessary for the production of vitamin D, the sun is also the most common cause of skin damage and skin cancer. “Photo-damage, not the aging process, has been estimated to account for 90% of age-associated cosmetic problems” (Ham et al., 2007, p. 616). The damage (photo or solar damage) comes from prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light from the environment or in tanning booths. Although the amount of sun-induced damage varies with skin type and genetics, much of the associated damage is preventable. Ideally, preventive measures begin in childhood, but clinical evidence has shown that some improvement can be achieved at any time by limiting sun exposure and using sunscreens regularly.

Skin cancers

Cancer of the skin (including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer) is the most common of all cancers. The exact number of basal and squamous cell cancers is not known for certain because they are not reported to cancer registries, but it is estimated that there are more than two million basal and squamous cell skin cancers found each year. Most of these are basal cell cancers. Squamous cell cancer is less common. Most of these are curable but melanoma, which accounts for less than 5% of skin cancer cases, has the greatest potential to cause death.

Actinic keratosis

Actinic keratosis is a precancerous lesion that may become a squamous cell carcinoma. It is directly related to years of overexposure to UV light. Risk factors are older age and fair complexion. It is found on faces, lips, hands, and forearms, areas of chronic sun exposure in everyday life. Actinic keratosis is characterized by rough, scaly, sandpaper-like patches, pink to reddish-brown on an erythematous base. Lesions may be single or multiple; they may be painless or mildly tender. The person with actinic keratoses should be monitored by a dermatologist every 6 to 12 months for any change in appearance of the lesions. Early recognition, treatment, and removal of these lesions is easy and important. Removal is aimed at preventing the possible conversion to a malignant lesion.

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant skin cancer. It occurs mainly in older age groups but is occurring more and more in younger persons. It is slow-growing, and metastasis is rare. A basal cell lesion can be triggered by extensive sun exposure, especially burns, chronic irritation, and chronic ulceration of the skin. It is more prevalent in light-skinned persons. It usually begins as a pearly papule with prominent telangiectasias (blood vessels) or as a scarlike area with no history of trauma. Basal cell carcinoma is also known to ulcerate. It may be indistinguishable from squamous cell carcinoma and is diagnosed by biopsy. Early detection and treatment are necessary to minimize disfigurement.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer. However, it is aggressive and has a high incidence of metastasis if not identified and treated promptly. Squamous cell cancer is more prevalent in fair-skinned, older men who live in sunny climates and is usually found on the head, the neck, or the hands. Individuals in their mid-60s who have been or are chronically exposed to the sun are prime candidates for this type of cancer. The lesion begins as a firm, irregular, fleshy, pink-colored nodule that becomes reddened and scaly, much like actinic keratosis, but it may increase rapidly in size. It may also be hard and wartlike with a gray top and horny texture, or it may be ulcerated and indurated with raised, defined borders. Because it can appear so differently, it is often overlooked or thought to be insignificant. The best advice to give older patients, especially those who live in sunny climates, is that they should be regularly screened by a dermatologist.

Melanoma

Melanoma, a neoplasm of the melanocytes, accounts for less than 5% of skin cancer cases, but it causes most skin cancer deaths. The number of new cases of melanoma in the United States has been increasing for at least 30 years. In recent years, the increases have been most pronounced in young white women and in older white men. It is one of the most common cancers in people under 30 years of age. Melanoma is more than 10 times more common in white Americans than in African Americans and slightly more common in men than in women (American Cancer Society, 2012).

Persons with a history of frequent blistering sunburns, use of tanning beds, skin cancer, or exposure to carcinogenic materials, or with sun sensitivity or a depressed immune system, are at particular risk. Increasing age along with a history of sun exposure increases one’s risk even further. White individuals with fair skin, freckles, and red or blond hair have a higher risk for melanoma. The legs and backs of women, and the backs of men, are the most common sites of melanoma. Melanoma has a high mortality rate because of its ability to metastasize quickly (American Cancer Society, 2012).

Melanoma has a classical multicolor, raised appearance with an asymmetrical, irregular border. It may appear to be of any size, but the surface diameter is not necessarily reflective of the size beneath the surface, similar in concept to an iceberg. It is treatable if caught early, before it has a chance to invade surrounding tissue. If the nurse finds any questionable lesions, the individual should be referred to a dermatologist immediately. The “ABCD” approach to assessing such potential lesions is used (Box 12-1).

Cancer

The nurse has an active role in the prevention and early recognition of skin cancers. This role may include working with community awareness and education programs, screening clinics, and direct care. In promoting skin health, the nurse is vigilant in observing skin for the changes that require further evaluation.

Age-related skin changes, such as thinning and diminished melanocytes, significantly increase the risk for solar damage and subsequent skin cancer. By far, the most important preventive nursing intervention is to provide education regarding the risks of photo and smoke damage. Preventive strategies include the use of sunscreens and protective clothing and limiting sun exposure.

Secondary prevention is in the form of early diagnosis. After a thorough clinical screening, the elder and his or her intimate partner can be taught to perform regular “checks” of each other’s skin, watching for signs of change and the need to contact a primary care provider or dermatologist promptly. For the person with keratosis and multiple freckles (nevi), photographing the body parts may be a useful reference. The adage “when it doubt, get it checked” is an important one and regular screenings should be a part of the health care of all older adults.

Other skin conditions

Combined with the skin changes discussed previously, older people who are more frail or physically ill and in hospitals or nursing homes are at more risk for the development of pressure ulcers as well as fungal skin infections.

Candidiasis (candida albicans)

The fungus Candida albicans (referred to as “yeast”) is present on the skin of healthy persons of any age. However, under certain circumstances and in the right environment, a fungal infection can develop. Persons who are obese, malnourished, receiving antibiotic or steroid therapy, or have diabetes are at increased risk. Candida grows especially well in areas that are moist, warm, and dark, such as in skinfolds, in the axilla and the groin, and under pendulous breasts. It can also be found in the corners of the mouth associated with the chronic moisture of angular cheilitis. In the vagina it is also called a “yeast infection.” If this is found in an older woman, it may mean that her diabetes either has not yet been diagnosed or is in poor control.

Inside the mouth a Candida infection is referred to as “thrush” and is associated with poor hygiene and immunocompromise, such as those with long-term steroid use, who are receiving chemotherapy, or who test positive for or are infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). In the mouth, candidiasis appears as irregular, white, flat to slightly raised patches on an erythematous base that cannot be scraped off. The infection can extend down into the throat and cause swallowing to be painful. In severely immunocompromised persons the infection can extend down the entire gastrointestinal tract.

On the skin, Candida is usually maculopapular, glazed, and dark pink in persons with less pigmentation and grayish in persons with more pigmentation. If it is advanced, the central area may be completely red and/or dark, and weeping with characteristic bright red and/or dark satellite lesions (distinct lesions a short distance from the center). At this point the skin may be edematous, itching, and burning.

The best approach to managing fungal infections is to prevent them, and the key to prevention is limiting the conditions that encourage fungal growth. Prevention is prioritized for persons who are obese, bedridden, incontinent, or diaphoretic. Attention is given to the adequate drying of bodily target areas after bathing, the prompt management of incontinent episodes, the use of loose-fitting cotton clothing and underwear, the changing of clothing when damp, and the avoidance of incontinence products that are tight or have plastic that touches the skin.

One of the best ways to dry hard-to-reach, vulnerable areas is with a hair dryer set on low. A folded, dry washcloth or cotton sanitary pad can be placed under the breasts or between skinfolds to promote exposure to air and light. Cornstarch should never be used because it promotes the growth of Candida organisms. Optimizing nutrition and glycemic control is also important.

The goal of treatment is to eradicate the infection. This includes not only the use of prescribed antifungal medication, but also the active involvement of the nurse to reduce or eliminate the conditions that created the problem. The affected area of the skin must be cleansed carefully and dried thoroughly before antifungal preparations are applied. A mild soap or cleansing agent, such as Cetaphil, should be used. Antifungal preparations come as powders, creams, and lotions. Because the latter two trap moisture, the powder is recommended. They are usually needed for 7 to 14 days or until the infection is completely cleared.

Antifungal medications include miconazole (Micatin), clotrimazole (Lotrimin), nystatin (Mycostatin), and econazole (Spectazole). Treatment of oral Candida infection includes mouth swishing and swallowing with an antifungal suspension and/or sucking on antifungal troches. Angular cheilitis is treated by application of a topical antifungal ointment to the corners of the mouth. If the Candida cannot be eliminated in the usual course of therapy, it may be necessary to use ketoconazole or fluconazole systemically for a prescribed period.

Pressure ulcers

Definition

The European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) and the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) constitute an international collaboration convened to develop evidence-based recommendations to be used throughout the world to prevent and treat pressure-related wounds. According to this group, a pressure ulcer is “an injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue resulting from pressure or in combination with shear, usually over a bony prominence” (EPUAP & NPUAP, 2009). As tissue is compressed, blood is diverted and blood vessels are forcibly constricted by the persistent pressure on the skin and underlying structures; thus cellular respiration is impaired and cells die from ischemia and anoxia. Intervention at any point in this development can stop the advancement of the pressure ulcer.

Just how much pressure can be endured by tissue (tissue tolerance) is highly variable from body location to location and person to person. Tissue tolerance is inversely affected by moisture, amount of pressure, friction, shearing, and age and is directly related to malnutrition, anemia, and low arterial pressure.

Prevalence

Older people account for 70% of all pressure ulcers (Jamshed & Schneider, 2010). Several studies have reported a higher prevalence and incidence of pressure ulcers among African Americans in nursing homes than other race groups, and these differences remain after adjustment for clinical risk factors and sociodemographic and facility characteristics (Cai et al., 2010; Howard & Taylor, 2009; Li et al., 2011).

Pressure ulcers occur in all settings across the continuum, with the highest incidence reported in hospitalized vulnerable older people undergoing orthopedic procedures (9% to 19%) and individuals with quadriplegia (33% to 60%). Baumgarten and colleagues (2009) reported that approximately one third of hip fracture patients develop at least one new pressure ulcer, at stage 2 or higher, within 32 days of hospital admission. The NPUAP reported that the prevalence of pressure ulcers in acute care settings ranged from 10% to 18%, with 2.3% to 28% in long-term care and 0% to 29% in home care. There is wide variability among institutions. Differences in sample characteristics and study methodologies affect these statistics, but it is clear that pressure ulcers are a significant problem in all settings (Jamshed & Schneider, 2010; Plawecki et al., 2010). Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) includes a goal of reducing the rate of pressure ulcer–related hospitalizations among older adults.

Cost and regulatory requirements

Prevention of pressure ulcers is seen as a “key quality indicator of nursing care and pressure ulcers are widely supported as a nursing sensitive outcome” (Jull & Griffiths, 2010, p. 531). Pressure ulcers are recognized as a geriatric syndrome and efforts at prevention have always been considered an essential nursing intervention, particularly in long-term care (Armstrong et al., 2008). “Though nursing homes have been grappling with increasingly tight regulatory standards regarding wound care for two decades, there have been no similar regulatory incentives for hospitals” (Levine, 2008).

In 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) included hospital-acquired pressure ulcers as one of the eight preventable adverse events. Hospitals will no longer receive additional reimbursement to care for a patient who has acquired pressure ulcers under the hospital’s care. Estimated annual costs for pressure ulcer treatment are from $9 to $11.6 billion per year in the United States. Medicare estimated in 2007 that each pressure ulcer added $43,180 in costs to a hospital stay (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2012).

Characteristics

Pressure ulcers can develop anywhere on the body but are seen most frequently on the posterior aspects, especially the sacrum, the heels, and the greater trochanters. Secondary areas of breakdown include the lateral condyles of the knees and the ankles. The pinna of the ears is another area subject to breakdown, as are the elbows and the scapulae. Heels are particularly prone to the development of pressure ulcers because they are small surfaces that receive a high degree of pressure. Older adults with diabetes are prone to the development of foot ulcers and are at higher risk of earlier death compared to those without diabetes (Brownrigg et al., 2012). Attention to foot care is essential when caring for an older adult with diabetes. More information on diabetes can be found in Chapter 17, and a discussion of foot care is included later in this chapter.

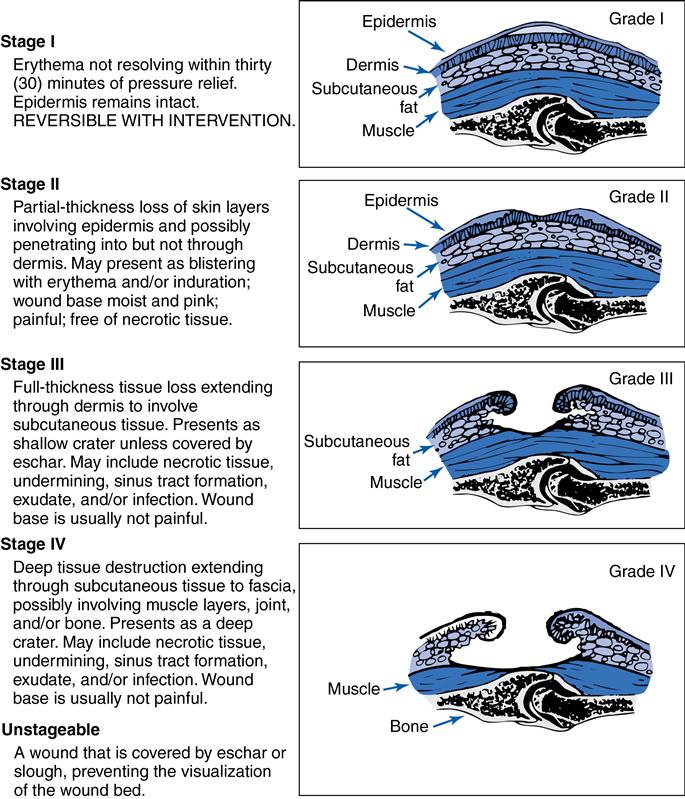

Classification

The EPUAP and NPUAP recommend a four-category classification of pressure ulcers. The NPUAP also describes two additional categories for the United States that do not fall into one of the established or classifiable categories: suspected deep tissue injury and unstageable or unclassified wound (Figure 12-1). Suspected deep tissue injury is defined by a localized area of intact skin or blood-filled blister, maroon or purple in color, caused by damage of the underlying soft tissue from shear and/or pressure (Plawecki et al., 2010).