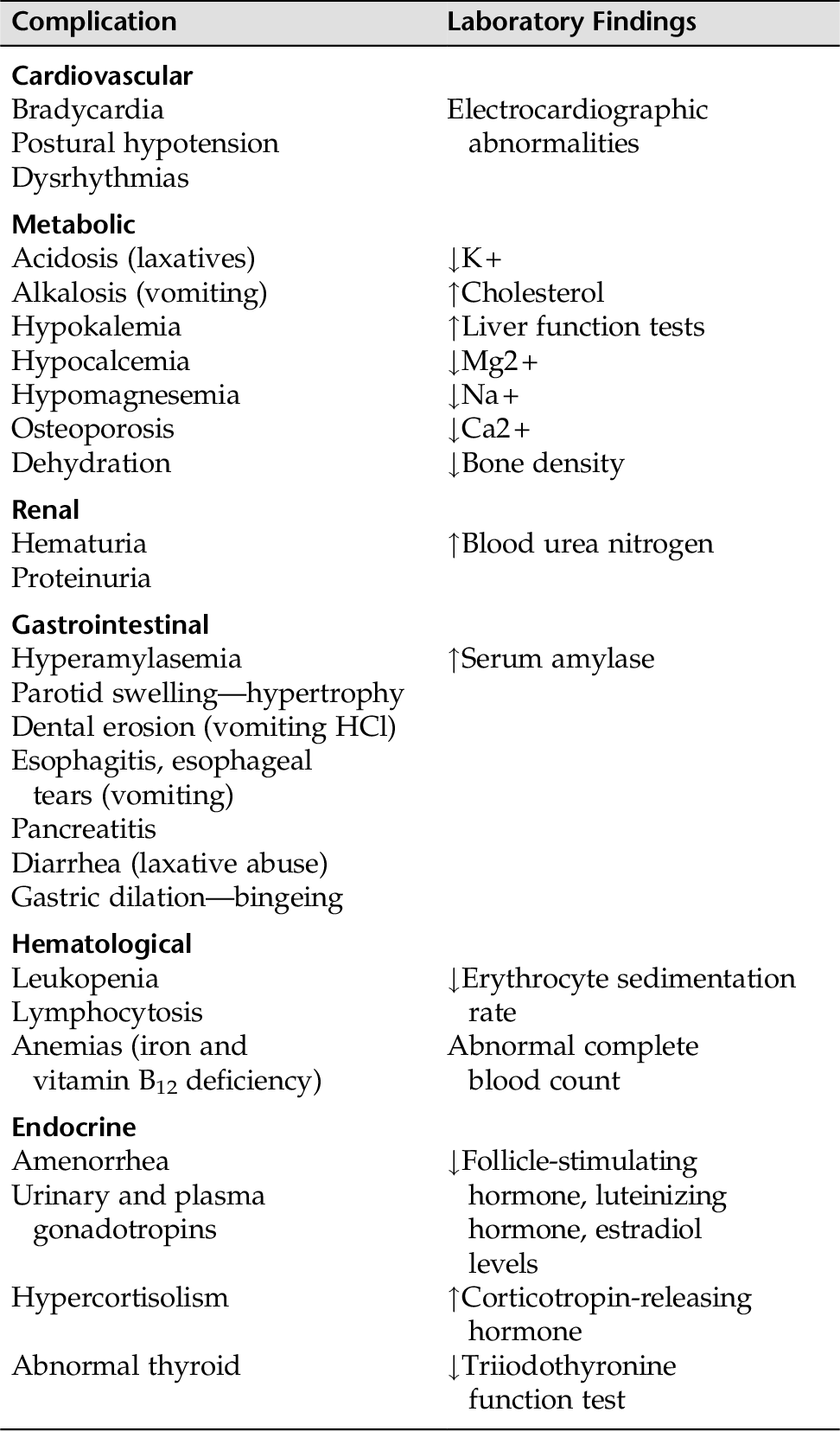

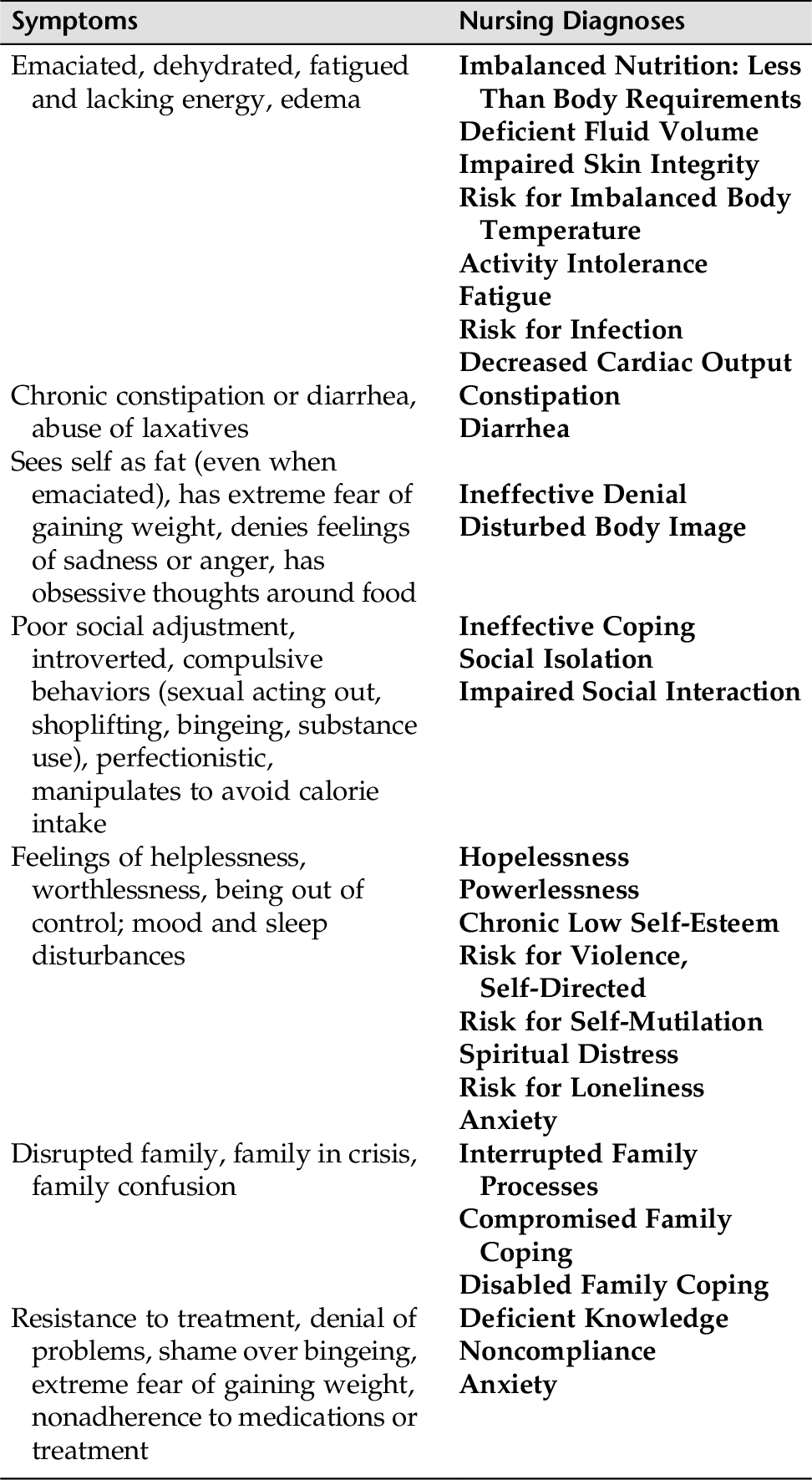

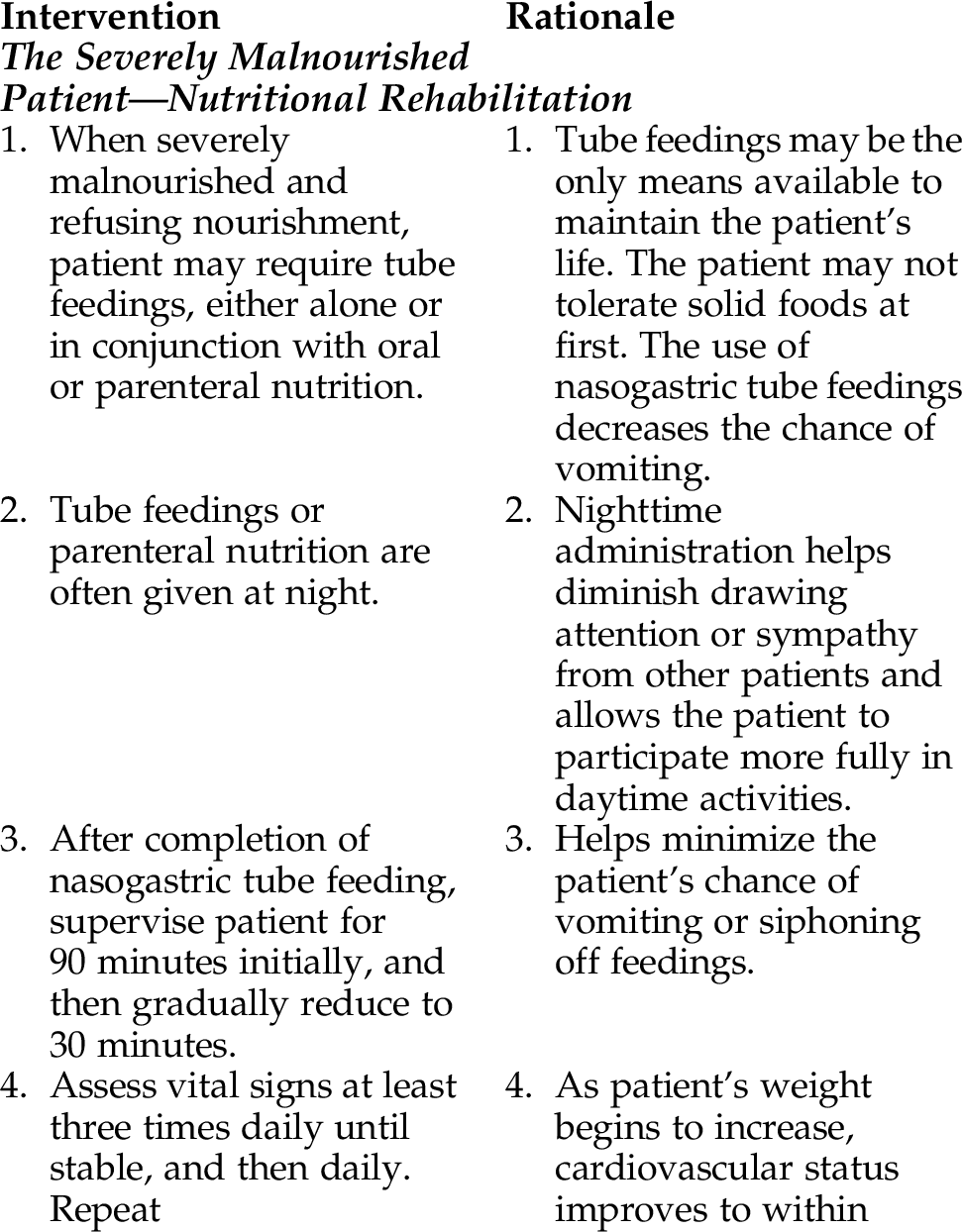

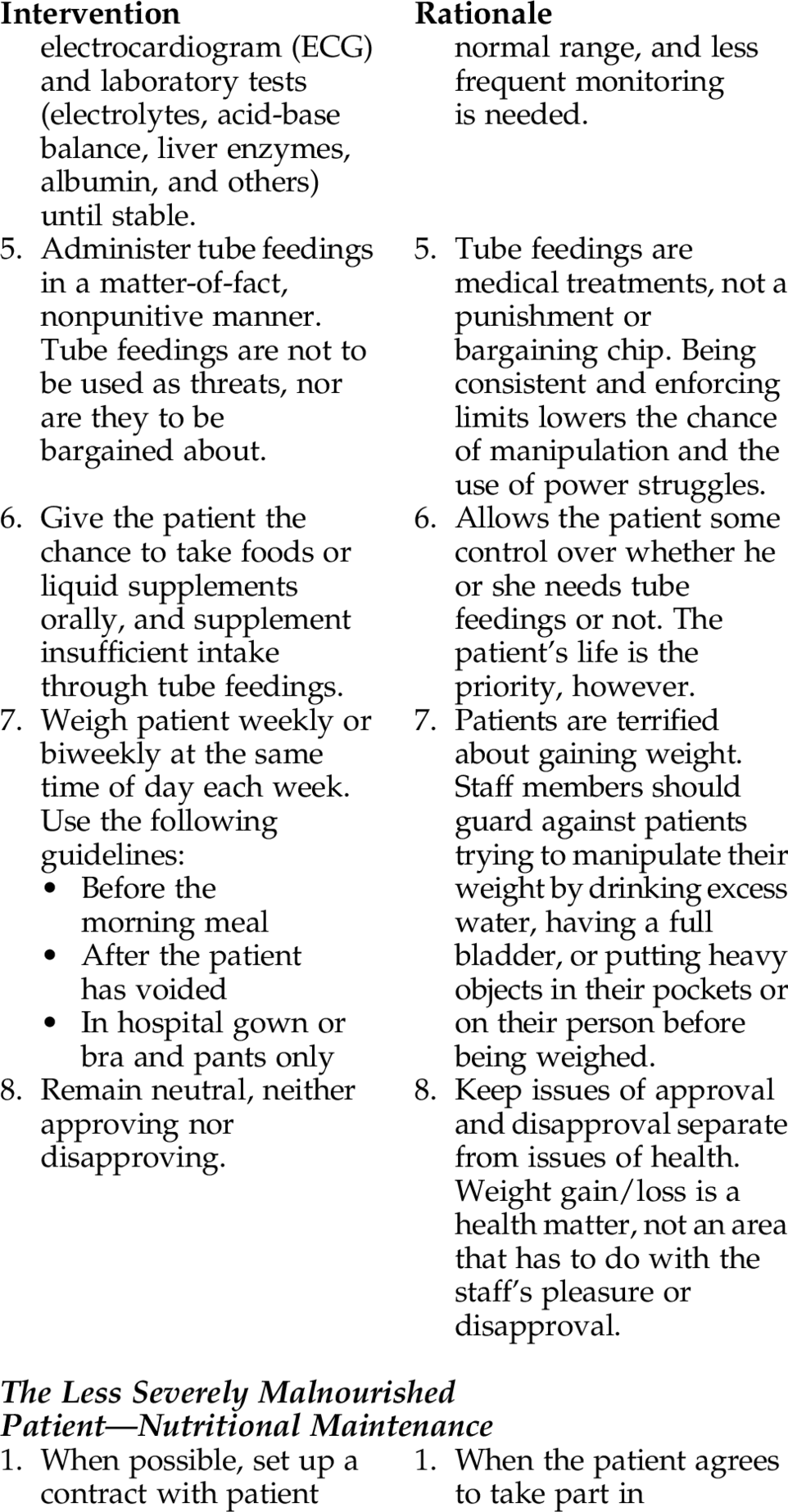

CHAPTER 12 People with eating disorders experience a severe disruption in their normal eating patterns and their perception of body shape and weight. These disorders are severe and disabling, and successful treatment entails long-term care and follow-up. Unlike most psychiatric conditions, these disorders can cause severe physiological damage. Table 12-1 lists some medical complications that can arise in patients with eating disorders. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are both potentially fatal eating disorders. Because anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are chronic, complex disorders, nursing interventions need to include actions to help minimize harm during the acute phase and prevent relapse. These disorders seem to have a familial component, and 20% to 50% of individuals with these disorders are reported to have a history of sexual abuse. These disorders predominantly affect adolescents both male and female and cause great suffering and frustration to families, friends, and loved ones. However, there is an increased incidence of eating disorder diagnosis in midlife, and often these are an exacerbation of a previously established dormant form of anorexia. Treating these disorders can pose a formidable challenge to the health care system. The two primary categories of eating disorders discussed in this section are anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Comorbid personality disorders frequently occur among patients with an eating disorder and account for approximately 50% of individuals with anorexia and 95% with bulimia. Some of the more prominent co-occurring disorders are the mood and anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, body dysmorphic disorders, personality disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and impulse-control disorders, to name a few. Most people associate eating disorders with females, but up to 10% (or more) of people with eating disorders are males. The DSM-5 (2013) has added binge-eating disorder (BED) to the category of eating disorders. BED is diagnosed when individuals engage in repeated episodes of binge eating after which they experience significant distress. BED is a psychiatric disorder. Obesity is a medical disorder. According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, the individual with BED experiences insatiable cravings at any time day and night; the disorder is thought to be rooted in poor body image and low self-esteem and tied to dysfunctional thoughts (ANAD, 2013). Anxiety, depression, and personality disorders often co-occur in BED. These individuals do not regularly use the compensatory behaviors (vomiting, use of laxatives) seen in bulimia nervosa. It is thought to account for 20% to 40% of individuals who seek treatment for obesity. The diagnosis of anorexia nervosa is based on psychological and physical criteria. Psychological criteria include an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat and a gross disturbance in body image. Cardinal symptoms for anorexia nervosa include dangerously low body weight measurements relative to age and gender of the patient (Ibrahim, 2013). Most cases of anorexia nervosa are seen in adolescent female patients, with more than 80% to 85% of cases developing between 13 and 20 years of age. Although most individuals with anorexia nervosa are adolescents, the disorder is being diagnosed in preadolescents, adults, and even older adults. Males account for approximately 19% to 30% of the younger patients diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. The issues and treatment modalities remain the same for both men and women. Characteristically, patients with anorexia are emaciated, but they still feel “fat” and want to hide their “ugly, fat body.” Patients with this disorder might have ritualistic eating patterns and compulsive behaviors; often feel hopeless, helpless, and depressed; and might feel that the only control they can exert in their life is through the food they eat. Anorexia nervosa is called the “deadly disease” because the mortality rate is higher with these individuals than in the general population. Besides starvation, death is also related to substance abuse and suicide. There is also a surprising increased rate of death from natural causes such as cancer. People with this disorder use two methods to control weight: 2. The restrictive approach uses low calorie intake and exercise (restricting type). The course of anorexia can be: • A single episode with weight and psychological recovery • Nutritional rehabilitation with relapses • An unremitting course resulting in death The disease has a mortality rate of 5% (most studies) to 20% (long-term studies on ultimate mortality rate over 20 years or longer). Death occurs from starvation, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, or suicide in chronically ill patients. Elliot (2007) has identified favorable and negative prognostic indicators for anorexia nervosa: 1. Favorable prognostic indicators: b. Return of menses c. Good premorbid school/work history 2. Negative prognostic indicators: a. Failure to respond to prior treatments b. Multiple hospitalizations c. Male d. Being married e. Premorbid disturbed family adjustment in childhood f. Co-occurring psychiatric condition(s) • Extreme fear of gaining weight • Poor social adjustment with some areas of high functioning (e.g., intellectual) • Odd food habits (hoarding, hiding food [e.g., in pockets, under plate]) • Hyperactivity (compulsive and obsessive exercise and/or secretive physical activity in an attempt to burn calories) • Mood and/or sleep disturbances • Obsessive-compulsive behaviors (e.g., eating only one pea at a time, arranging and rearranging food on the plate before each bite, or cutting food into tiny pieces and chewing each piece excessively) • Perfectionist • Introverted; avoids intimacy and sexual activity • Denies feelings of sadness or anger, and will often appear pleasant and compliant • Although cachectic, patients see themselves as fat (a sign of an unrealistic body image) • Families often have rigid rules and high expectations for their members • Emaciated physical appearance • Changes in cardiac status (e.g., bradycardia, hypotension, dysrhythmia) • Dry, yellowish skin • Amenorrhea, infertility • Hair loss, possible presence of lanugo (fine body hair covering) • Decreased metabolic rate • Chronic constipation • Fatigue and lack of energy • Insomnia • Loss of bone mass, osteoporosis • In patients who vomit or use laxatives to purge, loss of tooth enamel and scarring of the back of the hand from inducing vomiting, and enlarged salivary glands might be seen. Serum amylase level is often elevated. • Dehydration, edema • Laboratory abnormalities and medical complications (refer to Table 12-1) The nurse must be able to make a comprehensive nursing assessment, know when a medical or psychological emergency warrants hospitalization, and alert the medical staff. Refer to Appendix D-8 for a guide to help the nurse assess whether the patient with an eating disorder is a candidate for hospital admission. Determine if: 1. The patient has a medical or psychiatric situation that warrants hospitalization. 2. The family has information about the disease and knows where to get support. 3. The patient is amenable to attending appropriate therapeutic modalities and will be adherent. 4. Family counseling has been offered to the family or individual family members for support, or to target a family or individual family member’s problem. 5. A thorough physical examination with appropriate blood work has been done. 6. Other medical conditions have been ruled out. 7. The patient and family need further teaching or information regarding the treatment plan (e.g., psychopharmacological interventions, behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, family therapy, individual psychotherapy). If the patient is a candidate for partial hospitalization, can the patient and family discuss their function? 8. The patient and family desire a support group; if yes, provide referrals. Eating disorders have both physiological and psychological components. The aims of treatment are survival based: • Restore healthy eating habits. • Treat physical complications. • Address dysfunctional beliefs. • Intervene in those dysfunctional thoughts, feelings, and beliefs. • Deal with affective and behavioral issues. • Include family therapy when appropriate and possible. • Teach relapse prevention. The first steps in treating the anorexic patient include nutritional rehabilitation and weight restoration. Psychotherapy is not appropriate at this phase because there are profound psychological effects on mood and behavior from self-starvation. Hospitalization is warranted when emaciation is severe, vomiting is present, outpatient treatment has failed, or the patient has severe depression, suicidal feelings, or physical complications (refer to Appendix D-8). During hospitalization, treatment goals include: • Normalization of eating behavior • Change in the pursuit of thinness • Prevention of relapse Therefore, Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements is a primary nursing diagnosis. Because patients with anorexia have extreme distortions of body image (seeing themselves as fat when emaciated) and an intense fear of being fat, Disturbed Body Image is an important nursing diagnosis. A realistic perception of body size is important to help the patient refrain from the compulsive need to lose weight. There is real threat for self-harm; therefore, Risk for Self-Mutilation or Risk for Violence, Self-Directed might be appropriate diagnoses for some young patients. Refer to Chapter 17 for guidelines on assessment and care. Patients with anorexia are terrified about gaining weight and will do anything to prevent it; they frequently try to manipulate staff. Although briefly addressed here, Chapter 20 has an in-depth discussion on strategies for dealing with manipulative behaviors. It is important to understand that individuals with anorexia nervosa are notoriously disinterested in treatment. Gaining trust and cooperation can be difficult. Table 12-2 offers potential nursing diagnoses for individuals with eating disorders. 2. Do a self-assessment, and be aware of your own reactions that might hinder your ability to help the patient. Some nurses might: • Feel shocked or disgusted by the patient’s behavior or appearance. • Resent the patient, believing that the disorder is self-inflicted. • Feel helpless to change the patient’s behavior, leading to anger, frustration, and criticism. • Become overwhelmed by the patient’s problems, leading to feelings of hopelessness or setting rigid limits to feel more in control of the patient’s behavior. • Be swept up into power struggles with the patient, resulting in angry feelings in the nurse toward the patient. When any of these or other negative feelings toward the patient arise, supervision and/or peer review is needed to help shape the nurse’s perspective and lessen feelings of helplessness, guilt, need for control, frustration, or hopelessness. 3. When problems in the family contribute to the feeling of loss of control, family therapy has provided a significant improvement rate. 4. Individual therapy and group therapy are essential in treating patients with eating disorders. Treatment for anorexic patients often includes a behavior modification program, especially initially. Family therapy and family education are often key to a patient’s success. 5. Behavior therapy is often used to change the eating patterns of an anorexic patient who is seriously close to death. This is usually implemented after the patient has been tube fed to prevent death. 6. Refrain from focusing on the patient’s need to eat; recognize that other nonfood factors are the heart of the problem. 7. Monitor laboratory values, and report abnormal values to the primary clinician. • Food and fluid intake are within normal limits • Weight is maintained within a medically safe range • Patient’s electrolytes will be within normal limits by (date). • Patient’s cardiac status will be within normal limits by (date). • Patient will achieve 85% to 90% of ideal body weight. • Patient will commit to long-term treatment to prevent relapse by (date). • Patient will demonstrate regular independent nutritional eating habits by (date). • Patient will be free from physical complications. Patient will: • Increase caloric and nutritional intake, showing gradual increases on a weekly basis • Gain no more than _____ during the first week of refeeding, as decided by patient and health team • Exercise in limited amounts only when assessed to be both nutritionally and medically stable • Formulate with the nurse a nurse-patient contract facilitating a therapeutic alliance and a commitment to treatment on the part of the patient

Eating Disorders

OVERVIEW

Anorexia Nervosa

ASSESSMENT

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Psychosocial

Physiological and Endocrine Symptoms

ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Assessment Guidelines

Anorexia Nervosa

NURSING DIAGNOSES WITH INTERVENTIONS

Discussion of Potential Nursing Diagnoses

Overall Guidelines for Nursing Intervention

Anorexic Individual

Selected Nursing Diagnoses and Nursing Care Plans

Some Related Factors (Related To)

Inability to ingest or digest food or to absorb nutrients because of biological, psychological, or economic factors

Inability to ingest or digest food or to absorb nutrients because of biological, psychological, or economic factors

Restricting caloric intake or refusing to eat

Restricting caloric intake or refusing to eat

Excessive physical exertion resulting in caloric loss in excess of caloric intake

Excessive physical exertion resulting in caloric loss in excess of caloric intake

Self-induced vomiting related to self-starvation

Self-induced vomiting related to self-starvation

Defining Characteristics (As Evidenced By)

Weight loss 20% or more below ideal body weight

Weight loss 20% or more below ideal body weight

Reported food intake less than RDA (recommended minimum daily allowance)

Reported food intake less than RDA (recommended minimum daily allowance)

Diarrhea and/or steatorrhea (excess fat in the feces), abdominal cramping, pain

Diarrhea and/or steatorrhea (excess fat in the feces), abdominal cramping, pain

Sore buccal cavity (inner aspect of cheek)

Sore buccal cavity (inner aspect of cheek)

Increased growth of hair on body (lanugo)

Increased growth of hair on body (lanugo)

Serious medical complications resulting from starvation (e.g., electrolyte imbalances, hypothermia, bradycardia, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, edema)

Serious medical complications resulting from starvation (e.g., electrolyte imbalances, hypothermia, bradycardia, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, edema)

Outcome Criteria

Long-Term Goals

Short-Term Goals

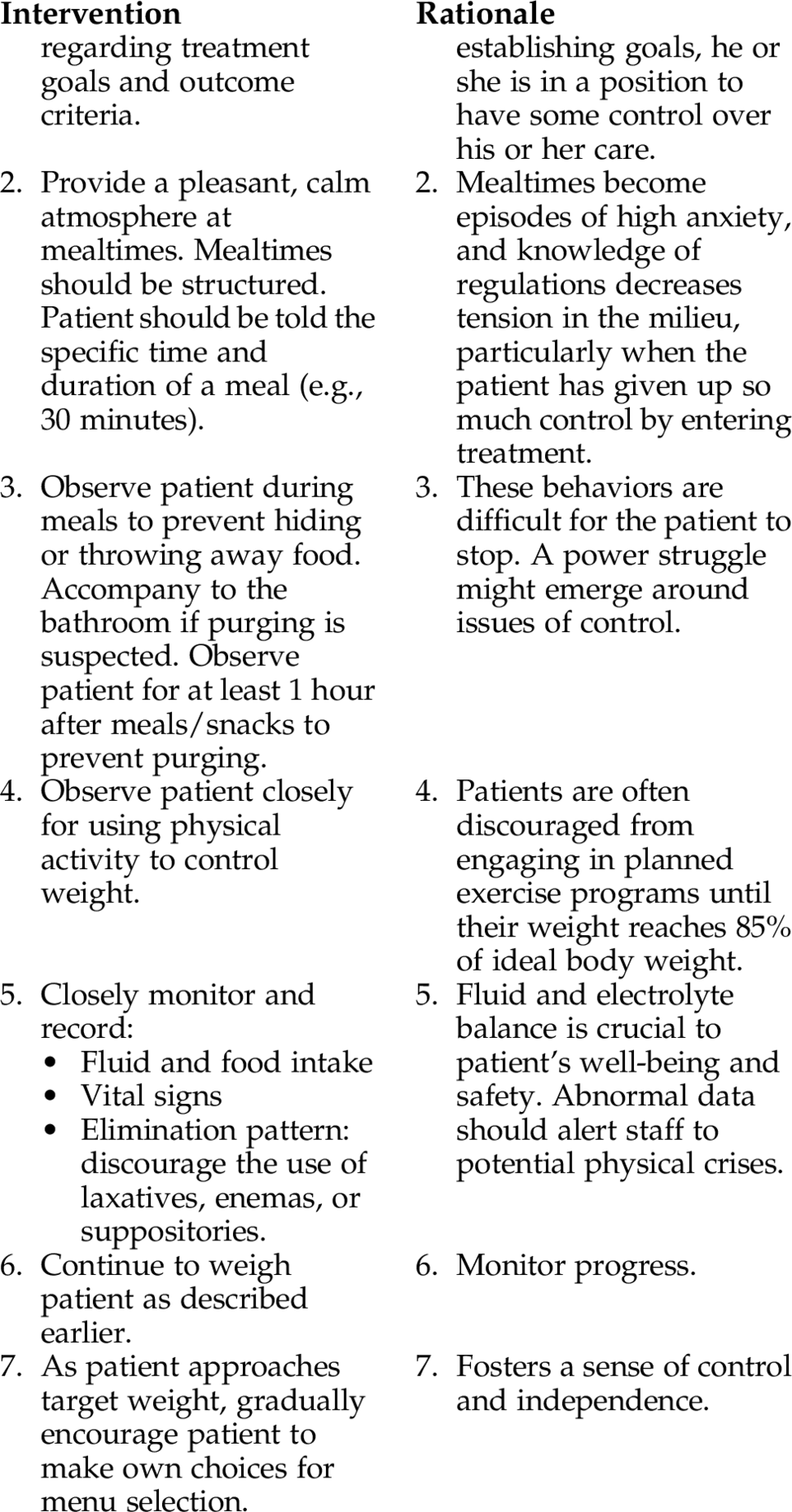

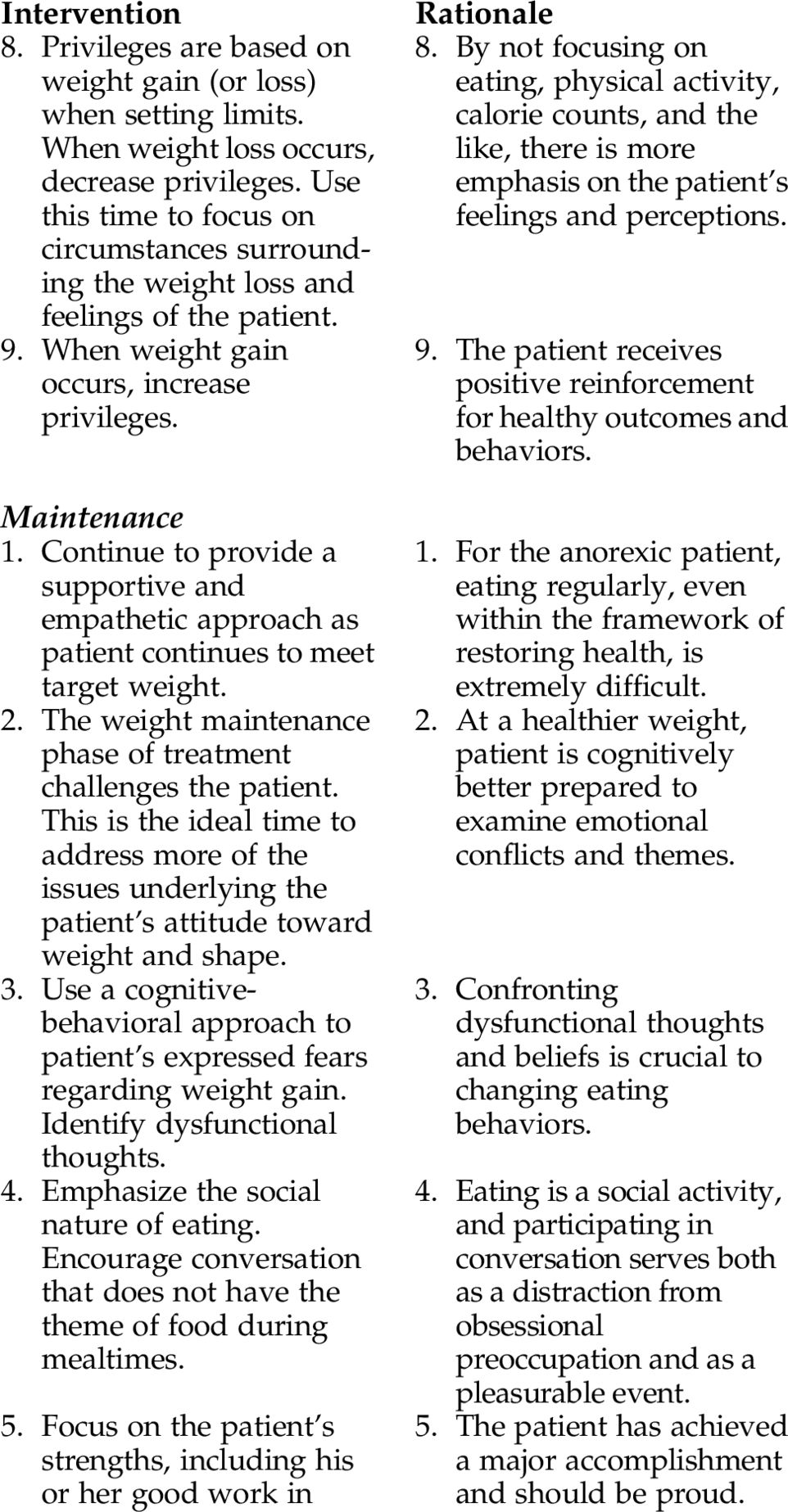

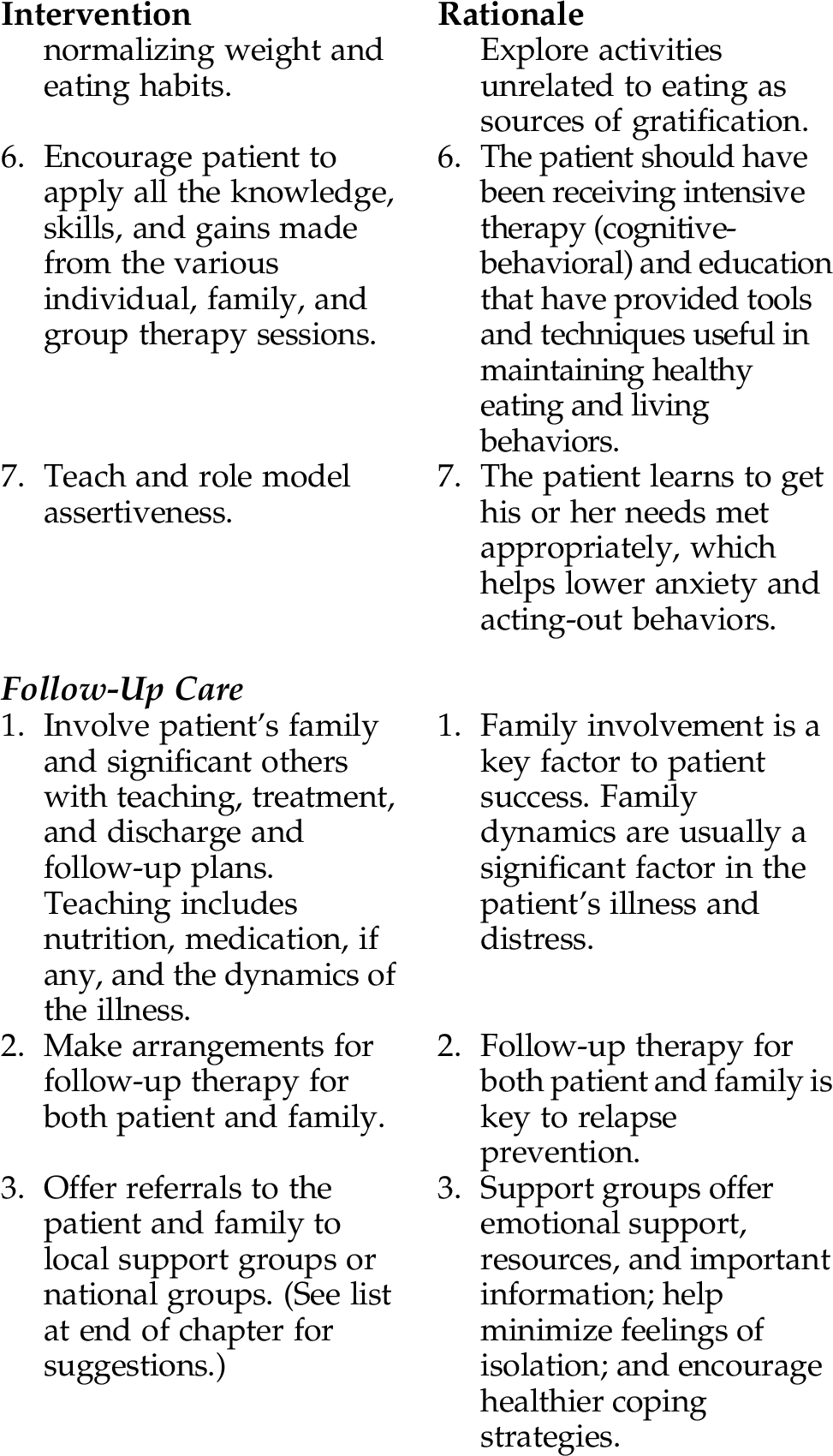

INTERVENTIONS AND RATIONALES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree