Economics of Health Care

Carrie Morgan and Melanie McEwen

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Discuss factors that influence the cost of health care.

2. Identify terms used in the financing of health care.

3. Discuss public financing of health care.

4. Discuss private financing of health care.

5. Discuss health insurance plans.

6. Describe trends in health care financing.

7. Describe the effects of economics on health care access.

Key terms

access

actuarial classifications

adverse selection

ambulatory care

capitated reimbursement

carrier

carve-out service

coinsurance

co-payment

cost containment

cost shifting

current procedural terminology (CPT) codes

deductible

diagnosis-related group (DRG)

effectiveness

flexible spending account

gatekeepers

health care providers

health insurance plans

health maintenance organization (HMO)

indemnity plan

managed care groups

managed care plans

mandates

Medicaid

Medicare

medigap insurance

outcomes

out-of-pocket expenses

preferred provider organization (PPO)

premiums

primary care provider

prospective payment system (PPS)

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

Economics represents the science of allocation of resources. Resources are commonly known as goods or services, for example, health care services. Economics affects all aspects of health care. Nurses have traditionally avoided the arena of health care economics, preferring to focus on the actual, direct care of the client. So strong is the feeling of social justice that some nurses express a reluctance to be informed of the individual client’s health care financing source for fear that this knowledge will influence their care. Community health nurses who deal with the medically underserved have had more experience in this area. However, even these nurses may have only rudimentary knowledge.

Health care costs continue to rise and consume a greater percentage of our nation’s resources. Nursing can no longer ignore the intricacies of health care financing. The health of individuals, families, and aggregates is influenced by economics. Economically disadvantaged individuals who have difficulty obtaining the basics, such as food and shelter, are less likely to have access to health care. Passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PL 111-148), however, should dramatically influence health care access. Indeed, when fully implemented, almost all citizens will have health insurance, either provided by their employers, through private purchase, or, for those from low income groups, through state and federal government sources (ie Medicare, Medicaid, CHIPs).

This chapter focuses on the economics of health care. It specifically discusses factors that influence health care costs, terminology of health care financing, and trends in health care economics. This chapter also addresses the future of health care financing. Box 11-1 presents terms and definitions that are important to the discussion of these topics.

Factors influencing health care costs

Historical Perspective

Until the 1930s, the predominant method of individual health care financing in the United States was self-payment. Health care providers charged a fee for the services they rendered, and the patient paid these out-of-pocket expenses. The price of the service was under the control of the provider and generally represented the cost of providing that service. A certain amount of “charity” services was expected. The assumption was that those who could pay would pay and those who could not pay should receive care and pay what they could.

The concept of public financing of health care for a specific aggreagate was restricted and varied from geographic area to area until the term public health came into common use.

The following types of hospitals existed:

This system worked well as long as the number of those who could pay outnumbered those who could not. During the Great Depression, with more than 25% of the population out of work, the number of those capable of paying for health care was greatly reduced. Because public financing of health care was limited, hospitals, physicians, and other providers of health care went bankrupt.

In 1929, schoolteachers in Dallas, Texas negotiated a prepaid health provision contract with Baylor Hospital. The teachers paid a sum of money each month, which guaranteed them access to health care through Baylor Hospital. The concept of insurance for health care proved extremely successful for Baylor Hospital. By 1939, this insurance plan had grown to include other groups and hospitals and became Blue Cross-Blue Shield (Koch, 2008).

Health insurance, or the idea of paying a small fee for guaranteed health care, appealed to the public. Societal concerns were mainly focused on sick care and acquisitions of curative therapies whenever needed. A public view that health insurance would provide freedom from fear that illness would impoverish them developed and prevails today. Health care providers envisioned guaranteed payment for their services (Higgins, 1997). During World War II, faced with a limited workforce and governmental restrictions on wages, employers began to see health insurance as a means of supplying workers’ benefits without granting a wage increase.

To extend this same “insurance” to the general population, the Social Security Act of 1935 was amended in 1965 to create Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare provided indemnity insurance to those over the age of 65 years, and Medicaid, a state-administered health plan, provided a source for financing health care for the poor and the disabled.

As a result of these health care resources, the majority of the population was protected by indemnity health care insurance from various sources. The indemnity plans lacked an incentive for limitation of use and few or no provisions for health promotion. The emphasis was placed on illness care, providers received a fee only when a service was rendered, and all costs of services were reimbursed. Insulated from rising health care costs, health care consumers demanded complex and technologically advanced services whenever illness struck. These demands for costly services represented the major driving force in rising health care costs.

By the 1980s, the first efforts to curtail health care costs were made by the federal government. With institution of the prospective payment system (PPS), hospital reimbursement for Medicare patients was based on a classification system that identified costs according to diagnosis and client characteristics. The PPS prompted an evolution towards managed care, dramatically altering health care financing through the end of the twentieth century, and into the first decade of the 21st century. Despite containment efforts, however, costs of health care have continued to rise.

The spiraling health care costs starting from the mid 1960s and persisting into the 21st century were fueled by the presence of technologic advances, society’s sense of entitlement to these therapies, a guaranteed payer, and the prevailing medical orientation toward curative measures. Prior to implementation of Medicare and Medicaid, national health expenditures represented less than 5% of the GDP. Forty years later, however, costs have risen exponentially, and now comprise about 17% of the GDP (CMS, 2010a).

Use of Health Care

According to economic principles, use is influenced by the existence of a desirable product, the demand for the product, and the availability of financial funding for a product. Health care is the product, and the demand for this product increases when funding is available. In an attempt to reduce unnecessary utilization, insurance plans began to limit coverage for certain services and people; thus the move toward ‘managed care’. Restrictions on use of health care, such as the establishment of a “gatekeeper,” requirement of preauthorization for some services, limited coverage for preexisting illnesses, and exclusion of those participants whose use was deemed exorbitant, have been instituted. These restrictions have had only limited success in curbing health care costs. In 2004, spending for health care in the U.S. was more than double that of other developed countries (i.e. those in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OCED]). Indeed, average per capita spending in that year was $2560 (8.9% of GDP) for OCED countries, compared with $6102 (15.3% of GDP) in the U.S. (Congressional Research Service, 2007).

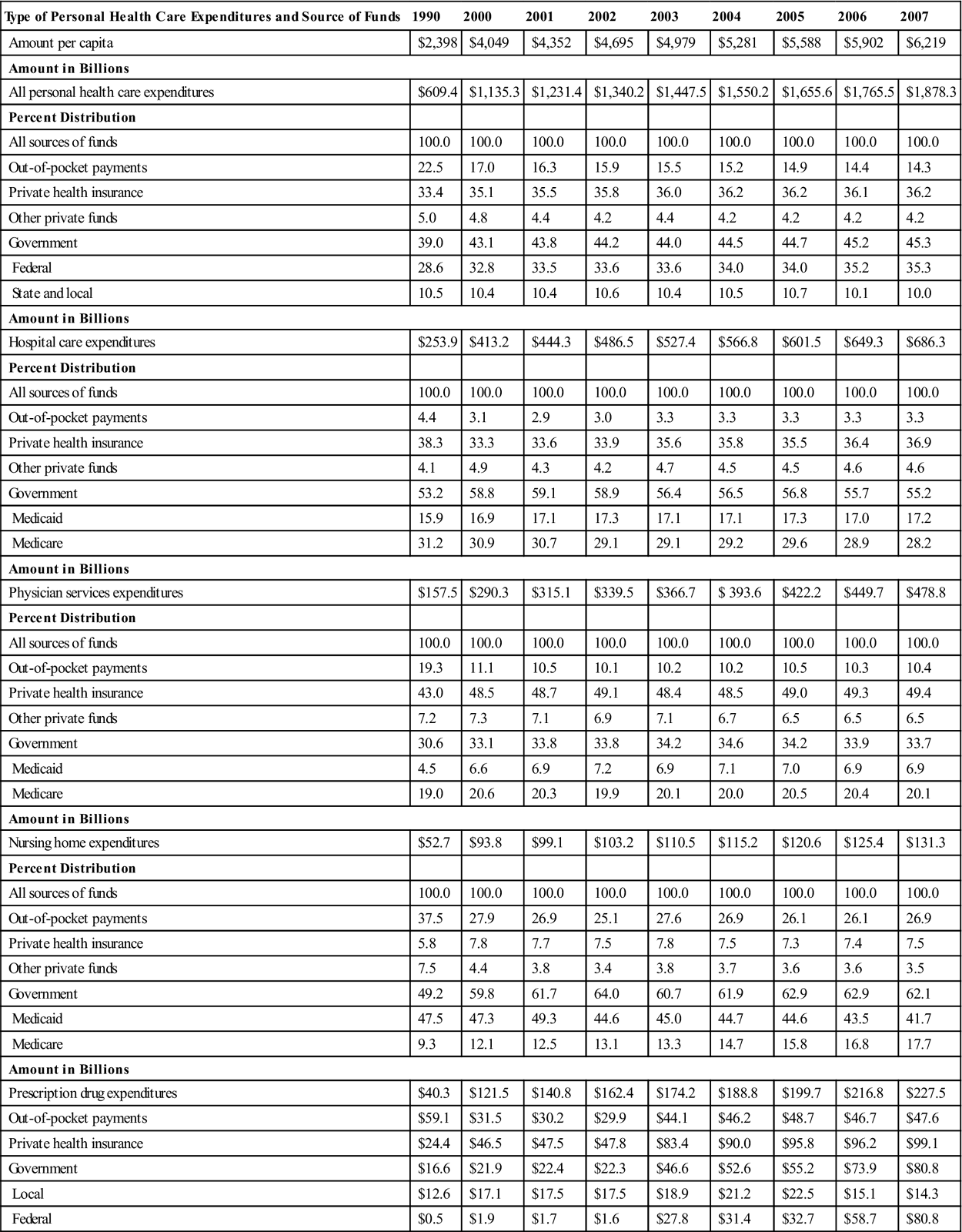

Expenses for health care vary according to types of care and sources of funding (Table 11-1). In 1960, out-of-pocket expenditure for physicians’ fees was 61.6% compared with 7.2% governmental expenditure for these fees. By 2007, the out-of-pocket expenditure for physicians’ fees was only 10.4%, and governmental expenditure proportion had risen to 33.7%. Similar patterns are evident for other health costs as a percentage of government financing has increased across all sectors. For example, by 2007, 55% of hospital costs and more than 62% of nursing home costs were paid by governmental sources (CMS, 2010a).

TABLE 11-1

| Type of Personal Health Care Expenditures and Source of Funds | 1990 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

| Amount per capita | $2,398 | $4,049 | $4,352 | $4,695 | $4,979 | $5,281 | $5,588 | $5,902 | $6,219 |

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| All personal health care expenditures | $609.4 | $1,135.3 | $1,231.4 | $1,340.2 | $1,447.5 | $1,550.2 | $1,655.6 | $1,765.5 | $1,878.3 |

| Percent Distribution | |||||||||

| All sources of funds | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Out-of-pocket payments | 22.5 | 17.0 | 16.3 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 15.2 | 14.9 | 14.4 | 14.3 |

| Private health insurance | 33.4 | 35.1 | 35.5 | 35.8 | 36.0 | 36.2 | 36.2 | 36.1 | 36.2 |

| Other private funds | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| Government | 39.0 | 43.1 | 43.8 | 44.2 | 44.0 | 44.5 | 44.7 | 45.2 | 45.3 |

| Federal | 28.6 | 32.8 | 33.5 | 33.6 | 33.6 | 34.0 | 34.0 | 35.2 | 35.3 |

| State and local | 10.5 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 10.0 |

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| Hospital care expenditures | $253.9 | $413.2 | $444.3 | $486.5 | $527.4 | $566.8 | $601.5 | $649.3 | $686.3 |

| Percent Distribution | |||||||||

| All sources of funds | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Out-of-pocket payments | 4.4 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| Private health insurance | 38.3 | 33.3 | 33.6 | 33.9 | 35.6 | 35.8 | 35.5 | 36.4 | 36.9 |

| Other private funds | 4.1 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Government | 53.2 | 58.8 | 59.1 | 58.9 | 56.4 | 56.5 | 56.8 | 55.7 | 55.2 |

| Medicaid | 15.9 | 16.9 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.1 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.0 | 17.2 |

| Medicare | 31.2 | 30.9 | 30.7 | 29.1 | 29.1 | 29.2 | 29.6 | 28.9 | 28.2 |

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| Physician services expenditures | $157.5 | $290.3 | $315.1 | $339.5 | $366.7 | $ 393.6 | $422.2 | $449.7 | $478.8 |

| Percent Distribution | |||||||||

| All sources of funds | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Out-of-pocket payments | 19.3 | 11.1 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 10.4 |

| Private health insurance | 43.0 | 48.5 | 48.7 | 49.1 | 48.4 | 48.5 | 49.0 | 49.3 | 49.4 |

| Other private funds | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| Government | 30.6 | 33.1 | 33.8 | 33.8 | 34.2 | 34.6 | 34.2 | 33.9 | 33.7 |

| Medicaid | 4.5 | 6.6 | 6.9 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.9 |

| Medicare | 19.0 | 20.6 | 20.3 | 19.9 | 20.1 | 20.0 | 20.5 | 20.4 | 20.1 |

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| Nursing home expenditures | $52.7 | $93.8 | $99.1 | $103.2 | $110.5 | $115.2 | $120.6 | $125.4 | $131.3 |

| Percent Distribution | |||||||||

| All sources of funds | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Out-of-pocket payments | 37.5 | 27.9 | 26.9 | 25.1 | 27.6 | 26.9 | 26.1 | 26.1 | 26.9 |

| Private health insurance | 5.8 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.5 |

| Other private funds | 7.5 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| Government | 49.2 | 59.8 | 61.7 | 64.0 | 60.7 | 61.9 | 62.9 | 62.9 | 62.1 |

| Medicaid | 47.5 | 47.3 | 49.3 | 44.6 | 45.0 | 44.7 | 44.6 | 43.5 | 41.7 |

| Medicare | 9.3 | 12.1 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 13.3 | 14.7 | 15.8 | 16.8 | 17.7 |

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| Prescription drug expenditures | $40.3 | $121.5 | $140.8 | $162.4 | $174.2 | $188.8 | $199.7 | $216.8 | $227.5 |

| Out-of-pocket payments | $59.1 | $31.5 | $30.2 | $29.9 | $44.1 | $46.2 | $48.7 | $46.7 | $47.6 |

| Private health insurance | $24.4 | $46.5 | $47.5 | $47.8 | $83.4 | $90.0 | $95.8 | $96.2 | $99.1 |

| Government | $16.6 | $21.9 | $22.4 | $22.3 | $46.6 | $52.6 | $55.2 | $73.9 | $80.8 |

| Local | $12.6 | $17.1 | $17.5 | $17.5 | $18.9 | $21.2 | $22.5 | $15.1 | $14.3 |

| Federal | $0.5 | $1.9 | $1.7 | $1.6 | $27.8 | $31.4 | $32.7 | $58.7 | $80.8 |

Data are compiled from various sources by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. From Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary: National health accounts, national health expenditures, Baltimore, 2009, The Author: www.cms.hhs.gov/statistics/nhe.

Lack of Preventive Care

Until recently, little to no incentive has existed to prevent illness or promote health. Curative measures have traditionally been the focus of health care. Soaring health care costs and an improved knowledge of health have heightened the public’s awareness of their obligation to assume responsibility for their health by amending many unhealthy behaviors. As a result, more people are demanding preventive health care from the provider and their health care contractors. Public financing of health care has increased funding for such preventive care as screening tests, periodic examinations, and immunizations. Use of these preventive health services has increased, but disparities persist relating to ethnic background and economic status (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2009). There continues to be a gap between the amount of funding available for preventive treatment modalities and funding for curative treatments.

Lifestyle and Health Behaviors

A healthy lifestyle does not ensure good health but has been shown to contribute to longevity and productivity (Harvard Men’s Health Watch, 2009). The five leading causes of death and illness can be positively affected by changes in lifestyle. Recent studies have found that a low-fat diet, exercise, maintaining a optimal weight, smoking cessation, and stress reduction can modify or even prevent most chronic illnesses. Smoking cessation reduces the incidence of lung cancer. Seat belt use reduces the severity of injuries incurred during moving vehicle accidents. Effective treatment of illness must be coupled with a change in lifestyle. In the near future, access to expensive and unique medical treatment will probably be influenced less by the patient’s ability to pay and more by the person’s commitment to compulsory lifestyle changes. For example, legislation has levied “sin taxes” on products whose use has been associated with chronic illnesses. The Commonwealth of Kentucky has the highest rate of adult smoking in the country. To offset the cost of Medicaid care, the legislature has levied a $0.30 per package cigarette tax. This income will be utilized to fund care for, prevention of, and research on chronic illness (Commonwealth of Kentucky Department of Revenue, 2005).

Old movies dramatize the change in lifestyle that has taken place in the past 30 years. The current “smoke-free” environment appears shocking when contrasted to the nonchalant attitude toward smoking that was pervasive 40 years ago. The advent of the Health Belief Model and Pender’s Health Prevention Model has given rise to numerous studies into methods of achieving lifestyle changes. The total effects of these changes are just now being seen. Meanwhile, the health care system must continue to contend with the results of years of unhealthy lifestyles.

Health care funding has changed to provide funding for preventive services. Some insurance plans provide monetary incentives, such as reduction in insurance premiums, for those who participate in behavioral changes toward a healthier lifestyle. Medicare will pay for many screening procedures performed for specific persons at specified times (CMS, 2010b). Funding for behavioral changes, however, is often limited, inadequate, or unavailable. Weight loss programs, support groups for smoking cessation, or participation in relaxation programs are not considered reimbursable treatment regimens, but more expensive pharmaceutical interventions are reimbursable.

Societal Beliefs

With the advent of such wonders as penicillin, society began to believe that the eradication of disease was just a few years away. More and more resources were dedicated to this elusive search. Armed with the belief that disease would soon be eliminated, societal interest in preventive care was limited. The general belief was that more money available for health care meant better health care and the greater likelihood that illness would be cured. Society views insurance as an economic shield protecting against all disease and illness. The belief in cure rather than prevention, combined with this financial safety net, encouraged society to become a passive participant in health care. The feeling “I don’t have to worry, I have insurance” became the pervasive societal thought (Sloan, 2004).

Health care professionals also were slow to embrace preventive care. Most efforts were directed toward curing illness. With what seemed to be an unending source of financing for curative care, illness prevention seemed counterproductive.

As health care costs accelerated at an alarming rate and technological advances did not keep up with the increase in illnesses, the health of society had to become a collaborative effort between society itself and the health care industry. Although the United States spends more money on health care than any other industrialized country, it ranks significantly behind many other countries in health status indicators (NCHS, 2009; OECD, 2008). People still expect the health care industry to cure them when they are ill, but there is an increase in preventive care interest. Interest in health education, health promotion, and behavioral changes has increased. Research into barriers and facilitators to lifestyle changes has increased but is not funded at the same level as curative measures (OECD, 2008).

Technological Advances

Modern society has come to expect miraculous technological advances. In response to this demand, and supplied with funding from various sources, technological advances have become too numerous to mention. The United States leads the world in laboratory and clinical research. People come from all over the world for education and to train in leading American centers for excellence (Weintraub and Shine, 2004). The United States exceeds other industrialized countries in the availability and use of these technological advances. For example, in 2006, France reported 5.3 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners for every 1 million population compared with the 26.5 MRI scanners available in the United States. For the same year, the United Kingdom performed angioplasties at a rate of 54.2 per 100,000 population and the United States performed 250.2 per 100,000 population (OECD, 2008). Technological advances can save the lives of people who would otherwise die. These advances, although remarkable, are expensive and result in 20% of the population consuming 80% of the health care resources. As the health care dollar shrinks, these advances raise ethical questions involving health care access and rationing. Restriction on technology can result in significantly reduced cost of health care, but the delays, inconvenience, and limitations to care with rationing will be strongly resisted by most Americans.

Aging of Society

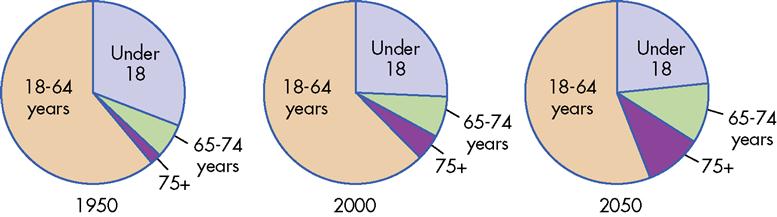

Health care expenditures increase with age. According to the most recent population projections, individuals older than 65 years constituted about 13% of the total population in 2010. This population is expected to increase to almost 21.5% by the year 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). Further, the percentage of those older than 85 years will increase from the present level of 1.9% of the total population to about 4.4% of the total population. This is concerning because health care costs increase dramatically as individuals age. For example, the average health care expenditures for Americans aged 65 to 75 years was $10,800 in 2004, compared with $25,700 for those 85 years and older (NCHS, 2009). The number of persons aged 20 to 64 years will decrease from 58.1% to 53.4% during the next 40 years (Figure 11-1). This means that the number of those consuming the greatest amount of health care resources will increase more rapidly than those who provide the monetary support for these resources. It has been estimated that nearly one third of expenditures for health care are incurred during middle age; half will be incurred during the senior years; and for those older than 85 years, one third will be incurred during the last year of life (Alemayehu and Warner, 2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree