Care of Patients with HIV/AIDS

Objectives

1. Summarize the modes of transmission for HIV.

2. List the tests used to diagnose HIV and to monitor the immune status of an HIV-positive patient.

3. Identify the signs and symptoms of AIDS.

6. Identify the nursing diagnoses needed for a patient with AIDS.

1. Perform nursing interventions needed for opportunistic infections.

2. Implement a teaching plan for a patient being started on HAART.

3. Review a nursing care plan for an HIV/AIDS patient hospitalized with a low CD4 count.

Key Terms

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (ă-KWĪRD ĭm-ū-nō-dĕ-FĬSH-ĕn-sē SĬN-drōm, p. 217)

anasarca (p. 226)

dermatomes (p. 221)

disseminated (p. 223)

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (ĭm-ū-nō-dĕ-FĬSH-ĕn-sē VĪ-rŭs, p. 217)

immune deficiency (ĭ-MŪN dĕ-FĬSH-ĕn-sē, p. 215)

immunocompetence (p. 215)

opportunistic infections (OIs) (ŏp-pŏr-tū-NĬS-tĭk ĭn-FĔK-shŭnz, p. 217)

prodrome (p. 221)

protease inhibitors (PIs) (prō-tē-ās ĭn-hĭb-ĭ-tŏrz, p. 222)

replicate (RĔP-lĭ-kāt, p. 217)

retrovirus (rĕ-trō-VĪ-rŭs, p. 217)

reverse transcriptase (rē-VĔRS trănz-SCRĬP-tās, p. 217)

sentinel infections (SĔN-tĭ-nĕl ĭn-FĔK-shŭnz, p. 219)

suppression (sū-PRĔ-shŭn, p. 217)

wasting syndrome (p. 229)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Immunocompetence occurs when a threat to the immune system stimulates certain physiologic responses (i.e., the vascular system, initiation of chemical responses, and the release of white blood cells) to protect the body against invasion from microorganisms or toxins.

Abnormal responses of the immune system are typically the result of an infection, medical therapy, or exposure to select toxins. An immune deficiency can occur when there is insufficient production of antibodies, immune cells, or both.

Acquired immune deficiency can result from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or administration of chemotherapy for cancer can temporarily reduce the ability of the bone marrow to produce white blood cells (WBCs).

Disorders of Immune Deficiency

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

In the early years, HIV was a fatal disease and treatment involved comfort measures and hospice care. Today, there is still no cure for HIV/AIDS, but there are approximately 16 approved HIV medications, and the prognosis for HIV has dramatically improved with early diagnosis. HIV is now considered a chronic controllable disease which requires adherence to prescribed medications, routine appointments, and recommended HIV tests (Figure 11-1, on the following page).

Pathophysiology

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is the most serious of the immune deficiency disorders. A person with AIDS also has HIV; however, a person with HIV does not necessarily have AIDS. Current research shows that those who are HIV positive will usually not develop AIDS if compliant with effective HIV treatment.

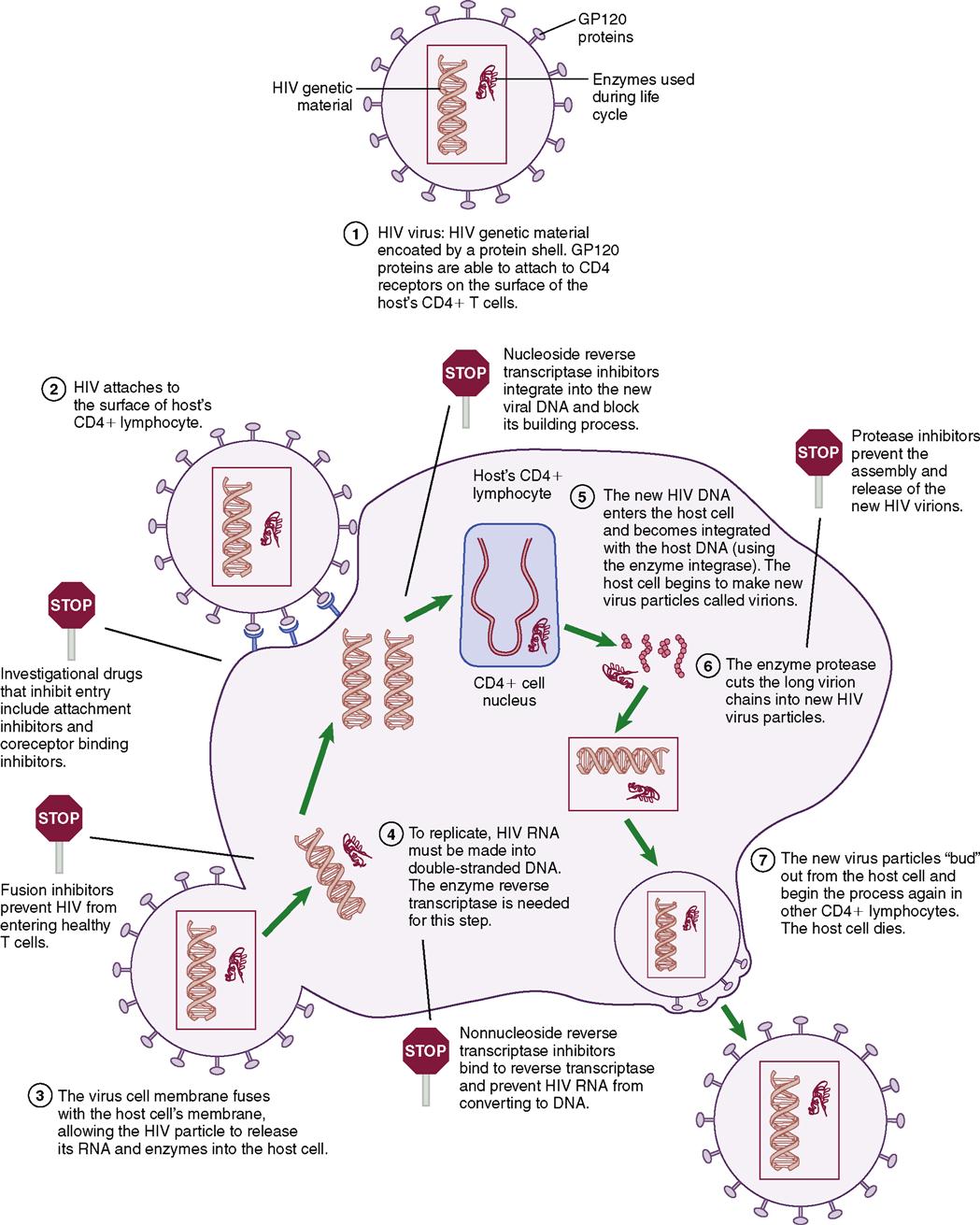

HIV is a retrovirus that integrates itself into the genetic material of the host cell, changing the proviral DNA and encoding structural, regulatory, and accessory proteins within the cell. A retrovirus differs from other viruses because of an enzyme called reverse transcriptase, which helps the virus reproduce in the host cell. HIV primarily attaches to the CD4 cell wall receptors found on lymphocytes and some monocytes. The virus must go through several stages (Table 11-1) before it can effectively infect a host cell. Once infected with HIV, the host cell and the ability of the cell-mediated immune response is seriously impaired. Once the infection occurs in the CD4 lymphocytes and produces HIV, the CD4 cell itself dies.

Table 11-1

| Stage | Action |

| Entry | Virus binds to envelope protein to CD4 molecule causing virus to fuse to host cell. Fusion releases RNA and HIV-1 proteins into the target cell cytoplasm. |

| Reverse transcription | RNA is transcribed into double-stranded DNA through the encoded protein. This phase is very error prone and can lead to mutations. |

| Integration | The new DNA inserts into the host gene. |

| Viral mRNA and protein expression | Viral protein production is activated and T cells are modified by HIV-1 protease. |

| Assembly and budding | Virus then attaches to host plasma membrane and new virions are produced. |

The most recent revision of the definitions of AIDS and HIV infection by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was done in 1993. (See Evolve for the classification system for HIV.) Suppression or inhibition of the immune response as a result of HIV infection is the cause of AIDS. HIV-1 is the most common cause of HIV infection in the United States, Europe, and Asia. HIV-2 is widespread in western Africa. Research shows that HIV-2 spreads at a lower rate, has a lower plasma viral load, takes longer to incubate, and persons with this strain have a lesser risk of developing full-blown AIDS (American Academy of HIV Medicine, 2007).

HIV-1 and HIV-2 are both retroviruses and have only ribonucleic acid (RNA) as their genetic material. When they replicate (reproduce), their genetic material is placed in the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of the host cell. The resulting new DNA continues the process of replication, and produces as many as 50 million to 2 billion viral particles a day. These viral particles are released from the host cell into the circulatory system, where they infect other cells, such as macrophages and lymphoid tissue.

The T cells that have the protein CD4 on their surface are known as CD4 positive (CD4+) and as T helper cells. Normally CD4+ T cells activate B cells, natural killer cells, and phagocytes. These cells participate in both cellular and humoral immunity. The infected person becomes more prone to opportunistic infections (OIs), including normal flora found in the body (see Chapter 6). The diagnosis of AIDS is usually made in an HIV-infected patient with a CD4 T-lymphocyte count less than 200 cells/µL or with a specific OI being diagnosed.

Transmission

Research has shown that HIV cannot be transmitted by casual contact, routine nursing care (which includes following Standard Precautions), or by household contact. The only mode of transmission is by exposure to HIV-infected blood, body fluids, or tissue (Box 11-1). Any break in skin or mucous membranes is an entry portal for HIV. The highest risks for becoming infected with HIV are: having unprotected sex (oral, vaginal, or anal) or sharing needles and syringes with an HIV-infected person and maternal-fetal exposure.

A CDC report in 2009 stated that as of 2007, there were 42,495 newly confirmed cases of HIV in the United States (CDC, 2009a). The largest proportion of new cases (53%) was found in men having sex with other men (known as MSM). The increased numbers of heterosexual cases may be from a bisexual MSM engaging in unprotected sex with a female partner. The second highest rate (32%) of HIV-positive cases is found in the heterosexual population, especially among those involved in the high-risk behaviors (CDC, 2009a).

An unsafe practice that is a known method of HIV transmission is to be the receptive partner in anal or vaginal intercourse without using some form of barrier precaution such as a latex condom. Participating in unprotected anal intercourse with an HIV-positive partner will increase the risk of exposure via the microscopic tears that can occur in the lining of the anus (a lining that is thinner than the vaginal walls).

Another unsafe practice is orogenital (fellatio or cunnilingus) or oroanal (rimming) stimulation without a barrier (dental dam). Contact with any body fluids, such as semen or vaginal secretions and blood, must absolutely be avoided when the partner has HIV.

There is no reason for HIV-infected individuals to completely discontinue sexual activity. Touch and various forms of intimacy are important parts of any relationship. However, there is a need to reduce the risk of transmitting the virus to others and to prevent exposure to other sexually transmitted infections, as additional infection is more difficult to treat when the immune system is compromised by HIV.

Tattoos and Body Piercings

To date, there have been no documented cases of HIV transmission from tattoos and body piercings. However, there have been a significant number of confirmed cases of hepatitis B transmission from these activities and HIV and hepatitis B are transmitted in the same manner. There is a risk if needles and instruments for tattooing are not properly disinfected and sterilized between uses and if leftover ink is used. For tattoos and piercings, it is important to use licensed businesses which follow blood-borne pathogen procedures and other safety measures (Lehman et al., 2010).

Blood Products

For more than 25 years, all blood, blood products, and prospective organ donors have been screened for blood-borne pathogens such as hepatitis and HIV. According to the CDC, the current risk of contracting HIV from receiving a blood transfusion, blood products, or a donated organ or tissue is extremely small, even in populations with a high incidence of HIV infection.

Vaccine Development

The International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, which includes a network of professional researchers and physicians in more than 23 countries, seeks effective treatments for AIDS and an effective HIV vaccine. HIV mutates rapidly and to date, almost 2 million mutations have been found among slightly fewer than 56,000 individuals infected with HIV (CDC, 2010). Mutations are found in newly infected as well as chronically infected individuals. People who take antiretroviral medications and have unprotected sex, or who share needles and syringes among intravenous drug users increase the risk of spreading the drug-resistant strains of HIV. Developing a vaccine is extremely challenging and currently, the primary emphasis is on preventing the spread of HIV.

Prevention Through Education

Providing basic understandable information helps to dispel the myths and fears associated with becoming infected with HIV. A nurse can contribute to prevention, in accordance with the Healthy People 2020 objectives to reduce the incidence of HIV/AIDS , by obtaining accurate facts related to HIV and by educating others—patients, colleagues, and the community—about their individual roles in helping to prevent the spread of this virus. Nurses must also assess for risk behaviors and implement individualized education.

, by obtaining accurate facts related to HIV and by educating others—patients, colleagues, and the community—about their individual roles in helping to prevent the spread of this virus. Nurses must also assess for risk behaviors and implement individualized education.

Signs and Symptoms

Some people infected with HIV have no symptoms for many years. A person’s preexisting health status influences the length of time needed for the humoral (antibody-mediated) and cellular (cell-mediated) immune responses to lodge a defense against HIV. Some newly infected individuals have no symptoms; other individuals may have flulike symptoms, which may be accompanied by maculopapular rash and lymphadenopathy. However, the HIV test may be negative at this phase of the disease.

As the immune system begins to fail, symptoms of sentinel infections (opportunistic infections that indicate immunosuppression) appear, such as oral thrush, recurrent vaginal yeast infections, or skin disorders. HIV has variable clinical presentations and latent periods without obvious symptoms. Often, the initial signs and symptoms of HIV infection are similar to flu: fever, fatigue, diarrhea, and loss of appetite. These symptoms may be ignored and the infected person typically does not seek health care until more obvious signs or symptoms begin to appear, such as skin rashes, night sweats, swollen lymph glands, and significant unintended weight loss. Symptoms may disappear and then recur and take longer to resolve. Additional illnesses (recurrent yeast infections or pneumonias, memory or movement problems) may prompt the person to seek treatment.

Diagnosis

Testing is available through a physician, local public health clinic, community agency, or by home test kit (Box 11-2). Home Access HIV-1 Test System is the only self-test kit that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The patient can anonymously purchase the kit, collect the required specimen, and send it to a specified lab and receive coded results through the mail. Other testing products on the market are not approved by the FDA because of their questionable methods or results; therefore patients must be advised about products.

Clinical laboratories and some physician offices have rapid HIV tests that can be performed with oral fluids and in some cases with urine. HIV tests search for antibodies to the virus. After exposure to HIV, there may be a delay before antibodies appear in the blood. A negative HIV test after initial exposure is not considered final; a second test, using a different test method than the first test, must be conducted 1 to 3 months later. The most common test used in a clinical laboratory setting is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Most HIV experts recommend that a confirmatory ELISA test be performed for any positive rapid HIV test. A positive HIV ELISA test is usually confirmed by performing a Western blot (WB) HIV gene sequence test. The HIV Western blot test can be negative, positive, or indeterminate. A negative Western blot test means that the positive ELISA test was a false positive. A positive HIV Western blot confirms the true positive nature of the ELISA positive test. An indeterminate test means that this test cannot be adequately read and is not an early positive test. The patient may also have other tests for concurrent hepatitis or sexually transmitted infections.

It is recommended that any sexually active adult between ages 15 and 65 be offered HIV testing at the time of a complete physical examination (CDC, 2006) . The age group included is a point of controversy. It is estimated that 25% of HIV-infected patients are unaware of their HIV infection and thus may be unintentionally infecting others (Box 11-3). The CDC has previously recommended HIV testing in pregnant women. If the patient elects to “opt out” of HIV testing, a note is made in the clinical record that the patient has declined HIV testing. It is now not necessary to get a specific request for HIV testing or perform pretest and post-test HIV counseling; however, it is important for the nurse to be familiar with state or local HIV testing requirements. The results of HIV antibody tests are confidential patient information.

. The age group included is a point of controversy. It is estimated that 25% of HIV-infected patients are unaware of their HIV infection and thus may be unintentionally infecting others (Box 11-3). The CDC has previously recommended HIV testing in pregnant women. If the patient elects to “opt out” of HIV testing, a note is made in the clinical record that the patient has declined HIV testing. It is now not necessary to get a specific request for HIV testing or perform pretest and post-test HIV counseling; however, it is important for the nurse to be familiar with state or local HIV testing requirements. The results of HIV antibody tests are confidential patient information.

Management of HIV Infection

When an individual is confirmed to have HIV, a comprehensive history and physical examination for health status should be conducted, including additional baseline laboratory and diagnostic studies (Table 11-2). A CD4 lymphocyte count should be performed to establish the stage of HIV infection and to assist in determining when to initiate antiretroviral therapy (ART) and prophylaxis for OIs.

Table 11-2

Additional Laboratory and Diagnostic Studies for Patients Newly Diagnosed with HIV*

| Laboratory/Diagnostic Study | Purpose |

| HIV antibody confirmatory study | Confirm diagnosis of HIV |

| CD4 count (reported as cells/µL) | Identify what stage of HIV infection patient may be in; can be used to determine when to start prophylactic therapy for OIs; should be obtained every few months to assess immune and/or therapeutic response and evaluate need for starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) |

| Quantitative plasma HIV-RNA level (viral load, reported as copies/mL) | Assess degree of clinical progression; help determine need for starting ART and if it needs adjustment |

| Drug resistance test (genotype: mutations, phenotype: viral replication) | Determine which ART will be most effective; prevent further development of drug-resistant strain of HIV |

| Complete blood cell (CBC) count | Assess for anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia; certain ARTs may be less effective if any of these are present |

| Comprehensive chemistry panel (includes electrolytes, BUN/creatinine, liver enzymes, cholesterol/triglycerides, glucose) | Determine baseline kidney and liver function, as well as lipid profile; results can be used to determine potential for complications with proposed ART |

| Sexually transmitted infections | Establish if treatment is needed |

| Toxoplasma gondii IgG | Detects prior exposure; if positive in the newly diagnosed HIV positive, patient is at increased risk of developing CNS difficulties when CD level is <100 µL |

| Hepatitis A, B, C | Determines if prior exposure to hepatitis and also indicates need for vaccination against hepatitis A and B |

*Additional testing may also include tuberculosis; Pap smear for women, and PSA level and prostate examination for men; CMV and eye examination along with routine health maintenance examinations based on age of patient.

Adapted from American Academy of HIV Medicine: AAHIVM Fundamentals of HIV Medicine for the HIV Specialist. (2007). Chicago: The Academy.

Choice of optimal therapy is based on clinical data and individual factors, such as past health status, medication history, quality-of-life issues, and patient expectations of therapy. The World Health Organization (WHO) has established standard criteria for staging HIV infection (Box 11-4). Genotyping or phenotyping blood tests to detect a drug-resistant strain of HIV are strongly recommended before starting drug therapy. Certain viral subtypes have a higher likelihood of developing drug resistance than others, and may require closer monitoring. Table 11-3 presents the current classes of antiretroviral medications with select nursing implications and side effects. Typically a three-drug regimen that often includes two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and one nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) will be prescribed. Occasionally, a protease inhibitor (PI) will be prescribed.

Table 11-3

Table 11-3

Classifications of Antiretroviral Medications for HIV/AIDS Therapy*

| Classification | Activity | Nursing Implications and Side Effects* |

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) | Block conversion from RNA to DNA thus preventing HIV genetic material from entering host cells | |

| Nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor | Prevents the virus from altering healthy CD4 cells | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|