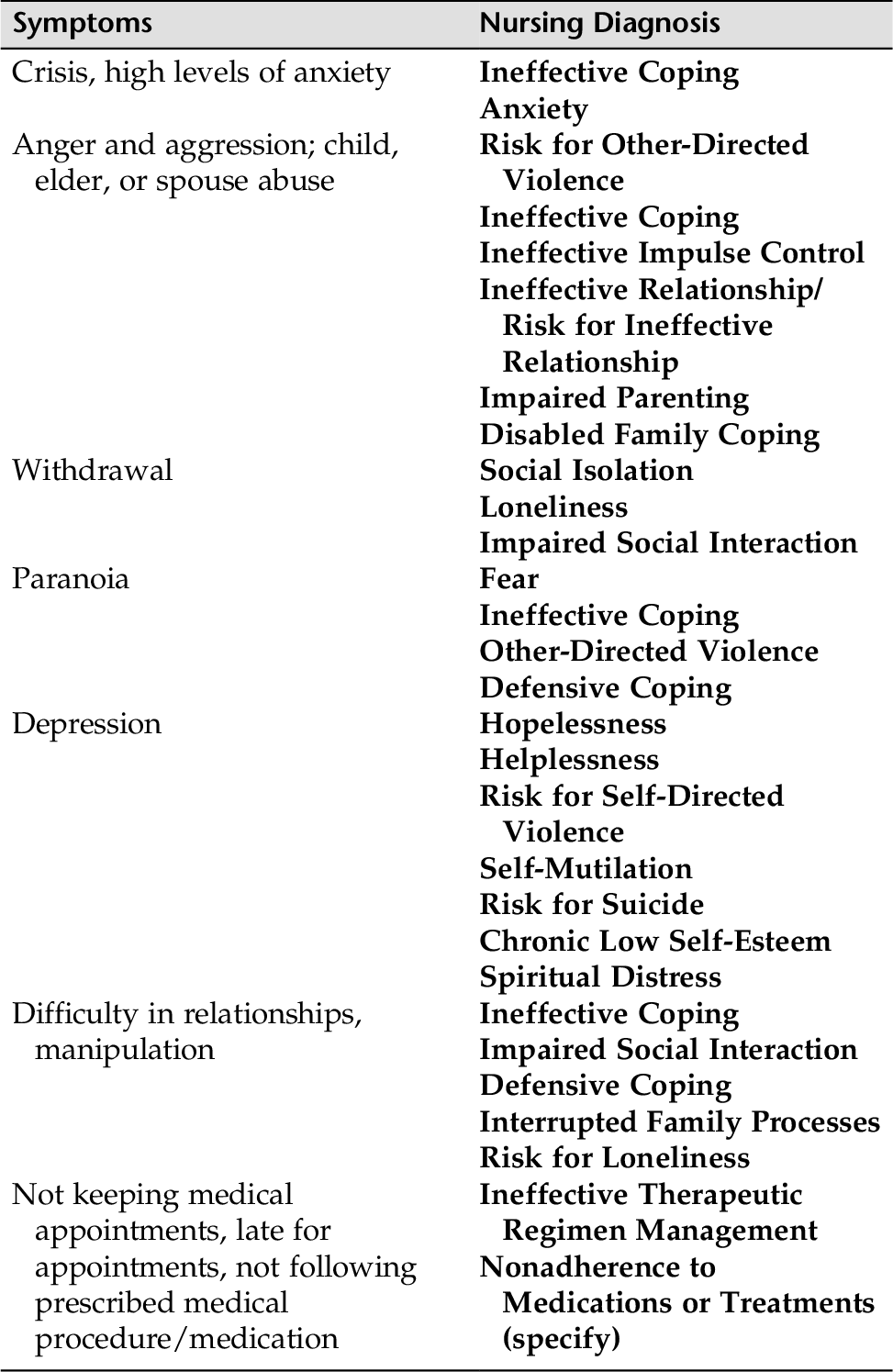

CHAPTER 10 Individuals with personality disorders (PD) present complex and difficult behavioral challenges for themselves and those around them. They are often referred to as “difficult patients.” Personality traits are the enduring styles we use to deal with the world—for example, shyness, rigidity, obsessiveness, manipulation, suspiciousness, and the like. In individuals with PDs, these traits are maladaptive, persistent, and inflexible and cause dysfunction and disruption in their relationships, jobs, social patterns, and more. The intensity and manifestation of presenting problems can vary widely among patients with PD, depending on diagnoses and specific characteristics. Some patients with PDs have milder forms of disability, whereas other patients’ symptoms present as extreme or even psychotic. However, all of the PDs have four common characteristics: 1. Inflexible and maladaptive responses to stress 2. Disability in working and loving 3. Ability to evoke interpersonal conflict in health care providers as well as family and friends 4. Capacity to have an intense effect on others (this process is often unconscious and generally produces undesirable results) Personality disorders frequently occur in conjunction with other psychiatric disorders and/or with general medical conditions. For example, both major depression and anxiety disorders have a high rate of comorbidity (co-occurrence) with PDs, estimated to occur in approximately 40% to 70% of patients. Comorbid PDs are likely to be found in patients with somatization, eating disorder, chronic pain, recurrent suicide attempts, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Boerescu, 2007). Individuals with a substance abuse problem might also have a comorbid PD, which can complicate the therapeutic working relationship and interfere with treatment. Because each PD has its own characteristics, personality traits, and effects on self and others, it is best to deal with them individually. The following sections describe the defining characteristics, identify some intervention guidelines, and offer the most recent treatment modalities for each PD. Some of the most problematic behaviors nurses are confronted with in the health care setting are similar for many of the PDs. These behaviors in part include manipulation (refer to Chapter 20), self-mutilation, suicide (Chapter 17), anger and hostility (Chapter 18), low self-esteem, ineffective coping and/or impaired social interaction, and nonadherence to medication or treatment (Chapter 21). Self-mutilation, low self-esteem, impaired social interaction, and ineffective coping are covered in this chapter. The other common nursing diagnoses of patients with PD are covered in separate chapters. All of these behaviors are commonly seen in a host of disorders, and the guidelines for intervention are similar for all patients. Although individuals with PDs might be hospitalized briefly during a crisis, generally long-term treatment takes place in clinics and community settings. The following discussion provides defining characteristics, guidelines for care, and treatments. • Bears grudges; is unforgiving of insults, injuries, or slights • Reads hidden, demeaning, or threatening meanings into benign remarks or events • Has difficulty establishing close relationships; usually works alone • Perceived as cold and unemotional, and does not share thoughts with others; lacks a sense of humor • Very critical of others, but has a great deal of difficulty accepting criticism • Prone to file lawsuits 1. Avoid being too “nice” or “friendly.” 2. Give clear and straightforward explanations of tests and procedures beforehand. 3. Use simple, clear language; avoid ambiguity. 4. Project a neutral but kind affect. 5. Warn about any changes, side effects of medications, and reasons for delay. Such interventions may help allay anxiety and minimize suspiciousness. 6. A written plan of treatment might help encourage cooperation. Paranoid patients will initially mistrust their therapist’s motives and find it difficult to share personal information. For that reason, therapy is often not sought or sustained among these patients. However, when a person with PPD does enter therapy, initially supportive therapy might help the patient experience trust and even begin to feel some amount of safety in an interpersonal relationship. If a therapeutic alliance can be achieved, cognitive and behavioral techniques might be useful to the patient. The focus is on counteracting fear and relieving stress and worry that are often expressed as hypervigilance and social withdrawal (Boerescu, 2007). Severe symptoms of paranoia can be attenuated with careful use of antipsychotic medication. • Neither desires nor enjoys close relationships, even within own family • Prefers to live apart from others and choose solitary activities. Has little interest in sexual activity with others, and might describe self as “a loner” • Often described as eccentric, emotionally cool/detached, displaying a flattened affect (no show of emotions) • Occupation often involves little interpersonal contact, although may invest enormous energy in non-human contact (e.g., mathematics, astronomy) • Evidence exists that some individuals with schizoid personality traits later develop schizophrenia and/or a delusional disorder. 1. Avoid being too “nice” or “friendly.” 2. Do not try to resocialize these patients, accept their need to be uninvolved. 3. A thorough diagnostic assessment might be needed to identify symptoms or disorders the patient is reluctant to discuss). A schizoid individual is apt to seek treatment only in a crisis situation, and only then to seek relief from acute symptoms. In some cases, supportive psychotherapy with cognitive-behavioral techniques can help reinforce socially outgoing behaviors. Group therapy might be appropriate if the individual needs of each patient are addressed. In some cases, social skills training groups might be an effective intervention, although individuals with this disorder often shy away from others. Short-term use of psychopharmacology might be appropriate for treating anxiety or depression. Low-dose antipsychotic medication can target symptoms such as anger, hostility, paranoia, and ideas of reference if such symptoms are part of the clinical picture. • Share many of the withdrawn, aloof, and socially distant characteristics listed for the schizoid PD patient described earlier in this chapter • Ideas of reference, odd beliefs, magical thinking, or unusual perceptual experiences, including bodily illusions, might be present • Excessive and unrelieved social anxiety frequently associated with paranoid fears • Lack of close friends and confidants • Inappropriate or constricted affect • Behavior or appearance that is odd, eccentric, or peculiar • Because of their illogical speech and unkempt appearances, they lack close friends and confidants • Some individuals diagnosed with schizotypal PD will go on to present with a full-blown schizophrenic illness 1. Respect the patient’s need for social isolation. 2. Be aware of the patient’s suspiciousness and employ appropriate interventions (refer to Chapter 9). 3. As with the schizoid patient, careful diagnostic assessment might be needed to uncover any other medical or psychological symptoms that might need intervention (e.g., suicidal thoughts). As with the schizoid patient, allowing distance and providing supportive measures might encourage the gradual development of a therapeutic alliance. Cognitive and behavioral measures might help patients gain basic social skills. Low-dose therapy with second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics can be effective in allowing the schizotypal patient to be more comfortable, less anxious, and less prone to suspiciousness, and in treating transient psychotic states. Four disorders appear to share dramatic, erratic, or flamboyant behavior as part of their presenting symptoms. As yet, no empirical evidence for this manner of clustering exists, but there does seem to be a high degree of overlap among these disorders. There is also a great deal of comorbidity with mental health disorders such as substance abuse and mood and anxiety disorders, as well as other personality disorders. Deceitfulness (use of aliases, conning others for personal profit or pleasure, repeated lying) • Blames others for their problems (externalize blame outward) • Consistent irresponsibility (failure to honor financial obligations, work responsibilities, family/parenting obligations) • Impassivity and repeated aggressiveness toward others • Total lack of remorse for physically or emotionally hurting or mistreating others or swindling or stealing from others • At times presents as charming, self-assured, and adept • Interaction with others through manipulation, aggressiveness, and exploitation; totally lacking in empathy or concern for others • Substance abuse is the most frequent comorbid disorder. • There is a significant familial pattern to criminality in general and ASPD in particular. • Set clear and realistic limits on specific behavior. • All staff involved should adhere to all limits. • Carefully document objective physical signs of manipulation or aggression when managing clinical problems. • Document behaviors objectively (give times, dates, circumstances). • Provide clear boundaries and consequences. 2. Be aware that antisocial patients can instill guilt when they are not getting what they want. Guard against being manipulated through feeling guilty. 3. Treatment of substance abuse is best handled through a well-organized treatment before counseling and other forms of therapy are started. Very few treatment modalities have proven successful. Nor is there any treatment of choice for ASPD. The most useful approach is to target specific problem behaviors that have been shown to be amenable to modification, combined with other therapies such as psychopharmacology and family therapy. Caregivers need to focus on avoiding being manipulated, and often need guidance on providing clear boundaries with consequences. Some positive results have been obtained through milieu programs (e.g., token economy systems and therapeutic communities). • Relationships with others are intense, unstable, and alternate between intense dependence and rejection. • Behaviors are often impulsive and self-damaging (e.g., spending, unsafe sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, binge eating). • Recurrent suicidal and/or self-mutilating behaviors are common, often in response to perceived threats of rejection or separation. • Chronic feelings of emptiness or boredom and an absence of self-satisfaction. • Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. • Intense affect is manifested in outbursts of anger, hostility, depression, and/or anxiety. • Intense and primitive rage often complicates therapy and takes the form of extreme sarcasm, enduring bitterness, and angry outbursts at others. • Major defense is splitting, which often manifests in pitting one person or group against another (good guy versus bad guy). • Splitting is only one form of manipulation that individuals with BPD use. • Rapid idealization-devaluation is a classic signal behavior suggestive of borderline psychopathology or some other primitive personality. • Transient quasi-psychotic symptoms might develop in the form of paranoid or dissociative symptoms during times of stress. 1. Set realistic goals, use clear action words. 2. Be aware of manipulative behaviors (flattery, seductiveness, guilt instilling). 3. Provide clear and consistent boundaries and limits. 4. Use clear and straightforward communication. 5. When behavioral problems emerge, calmly review the therapeutic goals and boundaries of treatment. 6. Avoid rejecting or rescuing. 7. Assess for suicidal and self-mutilating behaviors, especially during times of stress. Treating individuals with BPD is a challenge. One method has emerged that has been successful for many patients with BPD. Marsha Linehan (1993) developed a behaviorally based treatment that targets the highly dysfunctional behaviors seen in these patients. Her therapeutic approach is called dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). DBT has proven extremely effective in helping borderline individuals gain hope and quality of life. Therapy for a person with BPD is often marked by a period of improvement with alternating periods of worsening. Short-term hospitalization is not uncommon during periods of suicidal or self-mutilating behaviors or severe depression. Long-term outpatient therapy, and at times carefully chosen group therapy if appropriate for the patient, has provided improvement for many patients. A combination of psychotherapy and medication seems to provide the best results for treatment of patients diagnosed with BPD. Medications can reduce anxiety, depression, and disruptive impulses. Approximately 50% of individuals with BPD experience serious episodes of depression. Low-dose antipsychotics might prove useful for severely cognitively disturbed individuals. The newer antidepressants (SSRIs) have helped some BPD patients in dealing with their anger. The anticonvulsant carbamazepine has demonstrated some efficacy in decreasing the frequency and severity of behavioral dyscontrol episodes, suicidality, and temper outbursts (McGee & Linehan, 1997). Patients with BPD pose great challenges for nurse clinicians, and supervision is advised to help with the inevitable strong countertransference issues. • Show excessive emotionality and attention-getting behavior (e.g., display sexually seductive, provocative, or self-dramatizing behaviors) • Intense emotional expressions are shallow, with rapid shifts from person to person or idea to idea • Prone to describe more intimacy in a relationship than is there (e.g., show intense attention to a casual acquaintance) • Are suggestible (easily influenced by others or circumstances) • Others experience them as smothering, destructive; unable to understand and insensitive to anyone else’s experience • Without instant gratification or admiration from others, patients can experience depression and become suicidal. 1. Understand seductive behavior as a response to distress. 2. Keep communication and interactions professional, despite temptation to collude with the patient in a flirtatious and misleading manner. 3. Encourage and model the use of concrete and descriptive rather than vague and impressionistic language. 4. Teach and role-model assertiveness. Individuals with HPD use indirect means to get others to take care of them (physical attractiveness, charm, temper outbursts), and this can greatly complicate the therapeutic process. Therapeutic approaches used are psychoanalytic and cognitive-behavioral methods; however, research on the treatment of HPD is lacking. Most of the literature consists of case reports using various approaches (McGee & Linehan, 1997). • Exploit others to meet their own needs and desires • Come across as arrogant, and demonstrate a demeanor of “persistent entitlement” • Portray a demeanor of grandiosity, a need for admiration, and a lack of empathy for others • May openly agree to another’s demands, but often disrupts or sabotages other people’s projects or plans • May begrudge others for their success or possessions, feeling that they deserve the admiration and privileges more. • Relationships are characterized by superficiality, disruption (frequently provoke arguments), or control (consistently in power struggles). 2. Convey unassuming self-confidence. There have been no controlled trials of efficacy for any one therapeutic approach. The main approaches are supportive or insight-oriented psychotherapy. Milieu therapy might be useful for some NPD patients. Treatment difficulties are based on the patient’s inability to see another point of view other than their own because their own point of view regarding their needs is so ingrained and chronic. Because of this, it is impossible to move forward (Sadock & Sadock, 2010). Most patients do not seek treatment unless they seek treatment for a co-occurring major psychiatric disorder such as anxiety or depression. The following disorders are characterized by high levels of anxiety and the outward signs of fear. These personality types also show social inhibitions, mostly in the sexual sphere (e.g., shyness or awkwardness with potential sexual partners; impotence or frigidity). It is hard for these individuals to express irritation or anger, even in an interpersonal encounter that justifies these feelings. Inhibited patients tend to internalize blame for the frustrations in their lives, even when they are not to blame for these frustrations. • Might manifest an unusual degree of agreeableness or friendliness • These qualities are meant to enhance the dependent person’s ability to attach to another who can act as protector; urgently seeks another relationship as a source of care and support when a close relationship ends • Clinging is a common manifestation, but unfortunately this trait eventually alienates people and threatens to drive them away • Often perfecting the technique of clinging to others takes the place of outside interests, reading, cultivation of friends, or other sustaining activities • Have difficulty making everyday decisions without excessive advice and support from others • Go to excessive lengths to obtain nurture and support from others, even to the point of being mistreated or abused, or suffering extreme self-sacrifice • Need others to assume responsibility for most major areas of life; when others do not take initiative or take responsibility for them, their needs go unmet • Have difficulty expressing disagreements with others for fear of loss of support or approval • At risk for anxiety and mood disorders. DPD can occur in conjunction with BPD, avoidant personality disorder, and HPD • Fear not getting enough care, and often insist on having everything done for them 1. Identify and help address current stresses. 2. Try to satisfy patient’s needs, but set limits in such a manner that the patient does not feel punished, which might lead to withdrawal. 3. Strong countertransference often develops in clinicians because of the patient’s excessive clinging (demands of extra time, nighttime calls, crisis before vacations); therefore, supervision is well advised. 4. Teach and role-model assertiveness. A variety of therapies are useful and might all be appropriate during different phases while working on specific issues. Therapies include supportive therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and group therapy focused on cognitive change training, and social skills. Therapy is usually long-term. • Inflexible, rigid, and need to be in control • Perfectionist to a degree that it interferes with completion of work; cannot delegate • Overemphasis on work to the exclusion of friendships and pleasurable leisure activities • Preoccupied with details to the extent that decision making is impaired • Intimacy in relationships is superficial and rigidly controlled, even though might feel deep and genuine affection for friends and family • Financially extremely stingy, and it is difficult for the patient to part with personal objects, even if they are broken or worthless. • Highly critical of self and others in matters of morality, ethics, or values • The term compulsive refers to the behavioral aspects: preoccupation with lists, rules, schedules, and more. Other traits include indecisiveness, hoarding, and stinginess with money or time. • Often overwhelmed with a concern about loss of control (being too messy, sexy, or naughty); hence, the need to overcontrol and dominate people and situations in their lives. 2. Intellectualization, rationalization, and reaction formation are the most common defense mechanisms that patients with OCPD use. Individual psychotherapy, supportive therapy, and particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy might all be useful, depending on goals and the ego strengths of the patient. Therapeutic issues usually include those of control, submission, and intellectualization. Some medications found to be useful for the obsessional component are clomipramine (tricyclic antidepressant [TCA]), fluoxetine (SSRI), and clonazepam (anxiolytic). Group therapy can also be a useful adjunct to therapy. • Pervasive pattern of social inhibition; virtually all individuals with APD have social phobias • Strong feelings of inadequacy. Because these patients experience fear of rejection and/or criticism, they are very reticent in social situations • Avoid occupational activities that involve significant interpersonal contact because of fears of criticism, disapproval, or rejection • View themselves as socially inept, personally unappealing, or inferior to others • Might be inhibited and reluctant to involve themselves in new interpersonal situations or new activities • It is not uncommon for some patients with APD to have comorbid agoraphobia and OCPD as well as social phobia 1. A friendly, gentle, reassuring approach is the best way to treat patients with APD. 2. Being pushed into social situations can cause extreme and severe anxiety for APD patients. Each patient needs to be assessed individually. For example, if the patient has been taught fearfulness and withdrawal by avoidant parents, treatment would differ from that for the patient whose behavioral and cognitive traits stem from parental brutalization, incest, or sexual molestation in childhood. Because of the inherent social phobia, various forms of treatment can prove useful, such as cognitive therapy, desensitization, social skills training, and other cognitive-behavioral techniques. Group therapy has not proven advantageous over one-on-one supportive or exploratory psychotherapies. However, in the case of incest or other interpersonal trauma, special groups that include individuals with similar backgrounds are considered quite beneficial. Social anxiety might respond to a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). Benzodiazepine anxiolytics might help to contain brief panic episodes. The lowering of frightening anxiety can help patients engage more readily in therapy and can aid treatment adherence when patients are very fearful and anxious. In assessing for a PD, the patient’s history might reveal persistent traits held for long periods of time, causing distress or impairment in functioning. Refer to the sections on individual PDs for specific signs and symptoms. Does the patient: 1. Suspect others of exploiting or deceiving him or her? Bear grudges and not forget insults? 2. Detach self from social relationships? Not desire close relationships or being part of a family? Take pleasure in few if any activities? 3. Have a history of social and interpersonal deficits marked by acute discomfort? Have any cognitive or perceptual distortions? Does the patient: 2. Have a pattern of unstable and chaotic personal relationships? Have a history of suicide attempts or self-mutilation? Have chronic feelings of emptiness, or show intense anger, intense anxiety, and dysphoria? 3. Have a pattern of excessive emotionality and attention-seeking behaviors (e.g., sexually seductive or provocative)? Have very self-dramatic, theatrical, and exaggerated expressions of emotion? 4. Act grandiose, need admiration, and lack empathy for others? Have unreasonable expectations of favored treatment? Act interpersonally exploitive? Does the patient: 2. Have an excessive need to be taken care of, show clinging behaviors within relationships, have intense fear of separation? Have difficulty making everyday decisions without excessive amount of advice and reassurance from others? 3. Have a preoccupation with neatness, perfectionism, and mental and interpersonal control? Show rigidity and stubbornness? Patients with PDs rarely seek treatment. When they do, they rarely continue after the crisis is over. 1. Patient usually comes to the attention of the health care system through a crisis situation. 2. Antisocial patients most often come into the health care system through the courts by means of a court order. 3. Suicide attempts, self-mutilation, or substance abuse are common crises that bring individuals with PDs into treatment. Refer to Appendix D-6 for a sample questionnaire that can be used to identify personality traits. 2. PDs are often exacerbated following the loss of significant supporting people or in a disruptive social situation. 3. A change in personality in middle adulthood or later signals the need for a thorough medical workup or assessment for unrecognized substance abuse disorder. 4. Be cognizant that social stereotypes can influence the clinician’s judgment in that a particular diagnosis can be over- or underdiagnosed (e.g., for males or females because of sexual bias; because of social class or immigrant status). The data the nurse clinician collects provide information about the patient’s presenting problem or behaviors, emotional state, precipitating situations, and maladaptive coping behaviors. Patients with PDs present with any number of problematic behaviors. These behaviors can be pathological or maladaptive. Behaviors that are repetitive or rigid, or those that present an obstacle to meaningful relationships or functioning, are focused on during management of care. Many of these dysfunctional thought processes and behaviors are described earlier in this chapter in the individual presentation of each disorder. Short-term goals usually center on the patient’s safety and comfort and are pertinent to the patient’s physical and mental well-being. Often, the first goals for the management of an acute crisis are to evaluate the need for medication and to identify appropriate verbal interventions to decrease the patient’s immediate emotional stress. Keep in mind that patients have varied degrees of cognitive functioning and disabilities. What might be a short-term goal for one is likely a long-term goal for another. The goals cited here and in other chapters are helpful guidelines, but often the clinician is the one to best estimate patient strengths, capabilities, supports, and current level of functioning when setting specific time limits on goals. (For more on this topic, refer to Chapter 1.) Long-term goals are targeted for the long term and center on skill attainment. It is important to keep goals realistic. Changing lifelong behavior patterns that are inflexible and persistent takes a great deal of time, as well as engagement by the patient. Outcome criteria usually include the following areas: • Linking consequences to both functional and dysfunctional behaviors • Learning and mastering skills that facilitate functional behaviors • Practicing the substitution of functional alternatives during crisis • Ongoing management of anger, anxiety, shame, and happiness • Creating a lifestyle that prevents regressing (e.g., HALT: never getting too Hungry, too Angry, too Lonely, or too Tired) • Nursing crisis intervention strategies PD patients often act very impulsively. The nurse will be called on to intervene in many acting-out behaviors, often marked by impulsivity, such as self-mutilation and/or suicide attempts, anger and hostility toward the nurse clinician, extreme paranoia and blaming others for problems, manipulation and splitting, and intense anxiety. Acting-out behaviors are often most intense during the initial phases of therapy. Dealing with patients when they are acting out, especially during crises, takes persistence, patience, and learned skill on the part of the clinician. Some of the more common behavioral defenses PD patients employ require rigorous interventions. Because it is impossible to deal with all the problem areas of the 10 PDs, we will identify common behaviors for which all nurses are encouraged to develop skills. Common phenomena related to PD patients are (1) manipulation, (2) self-mutilation/suicide attempts, (3) intense low self-esteem, (4) intense anxiety, (5) anger and physical fighting, (6) projecting identification and blame to others, and (7) impulsivity. PD patients are often very demanding of health care personnel and others. Four common phenomena and nursing diagnoses are presented here: Risk for Self-Mutilation (scratching, burning, cutting), Chronic Low Self-Esteem, Impaired Social Interaction, and Ineffective Coping. Nursing interventions for minimizing and preventing manipulation are presented in Chapter 20. Suicide is covered in Chapter 17. Intense anger and hostility are addressed in Chapter 18. Individuals with PDs have great difficulty getting along with others and often elicit intense negative feelings from others. The following behaviors are found in a variety of combinations: demanding, angry, fault finding, suspicious, insensitive to the needs of others, manipulative, clinging, at times withdrawn, and often intensely lonely. Therefore, the interpersonal relationships of those with PDs are often chaotic and unsatisfying for all concerned. Impaired Social Interaction (Defensive Coping/Avoidance, Ineffective Coping) are key nursing diagnoses for individuals with PD; these problems are always present, most often in response to intense feelings of powerlessness. Table 10-1 identifies other possible nursing diagnoses.

Personality Disorders

OVERVIEW

Paranoid Personality Disorder (PPD)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

Schizoid Personality Disorder

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

Schizotypal Personality Disorder*

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

Histrionic Personality Disorder (HPD)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

Dependent Personality Disorder (DPD)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

Avoidant Personality Disorder (APD)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Nursing Guidelines

Treatment

ASSESSMENT

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Assessment Tools

Assessment Guidelines

Personality Disorders

NURSING DIAGNOSES WITH INTERVENTIONS

Discussion of Potential Nursing Diagnoses

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree