Health Care System

Anita W. Finkelman

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1. Analyze landmark health care legislation and its influence on the delivery system.

4. Describe the roles of the members of the health care team.

6. Discuss future concerns for the health care delivery system.

Key terms

accreditation

alternative therapies

client rights

community health center

health care reform

managed care

managed care organizations (MCOs)

Medicaid

Medicare

outcomes measures

public health

quality care

telehealth

Additional Material for Study, Review, and Further Exploration

The health care system of the United States is dynamic, multifaceted, and not comparable with any other health care system in the world. It is regularly praised for its technological breakthroughs, frequently criticized for its high costs, and often difficult to access by those most in need. This chapter describes landmark health care legislation, the components of the health care system, critical health care organization and provider issues, and the role of government in public health and health care reform and presents a futuristic perspective.

Major legislative actions and the health care system

An examination of the major legislative actions that federal and state governments have taken and recognition of their influence on health and health care delivery are critical to understand the evolution of the health care system in the United States. Throughout the twentieth century, the U.S. Congress enacted bills that had a major influence on the private and public health care subsystems. Legislation pertaining to health increased in scope in each decade of the twentieth century, with the goal of improving the health of populations and coping with changing health care needs. During the last two decades, concerns about an increase in health care costs and the growth of managed care stimulated even more legislation. Indeed, health care reform/health insurance reform were major issues during the 2008 presidential election. Further, throughout much of 2009, Congress debated numerous bills and amendments proposed to help reduce costs, increase access, and improve quality.

Federal Legislation

The following discussion describes some of the landmark federal laws that have influenced health services and health care professionals. These are summarized in Table 10-1.

TABLE 10-1

Critical Federal Legislation Related to Health Care

| Date | Legislation |

| 1906 | Pure Food and Drugs Act |

| 1912 | Children’s Bureau Act |

| 1921 | Sheppard-Towner Act |

| 1935 | Social Security Act |

| 1944 | Public Health Act |

| 1945 | McCarren-Ferguson Act |

| 1946 | Hill-Burton Act |

| 1953 | Department of Health, Education and Welfare as a cabinet-status agency; in 1979 divided into U.S. Department of Education and DHHS |

| 1956 | Health Amendments Act |

| 1964 | Nurse Training Act |

| 1965 | Social Security Act amendments: Title XVIII Medicare; Title XIX Medicaid |

| 1970 | Occupational Safety and Health Act |

| 1972 | Social Security Act amendments: Professional Standards Review Organization; further benefits under Medicare and Medicaid, including dialysis |

| 1973 | Health Maintenance Act |

| 1974 | National Health Planning Resources Act |

| 1981, 1987, 1989, 1990 | Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Acts |

| 1982 | Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act |

| 1985 | Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act |

| 1988 | Family Support Act |

| 1990 | Health Objectives Planning Act |

| 1996 | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| 1996 | Welfare Act |

| 2004 | Nurse Reinvestment Act |

| 2003 | Medicare Reinvestment Act |

| 2008 | Mental Health Parity and Addictions Equity |

| 2010 | Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act |

• Medicare, Title XVIII Social Security Amendment (1965): This federal program, administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (formerly Health Care Financing Administration [HCFA]), pays specified health care services for all people 65 years of age and older who are eligible to receive Social Security benefits. People with permanent disabilities and those with end-stage renal disease are also covered. The objective of Medicare is to protect older adults and the disabled against large medical outlays. The program is funded through a payroll tax of most working citizens. Individuals or providers may submit payment requests for health care services and are paid according to Medicare regulations. See Chapter 11 for more information on Medicare.

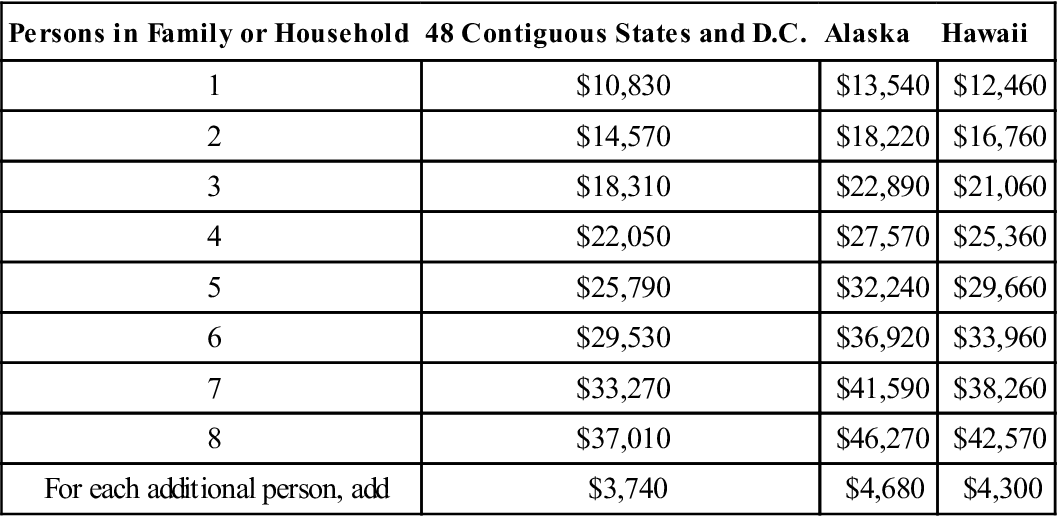

• Medicaid, Title XIX Social Security Amendment (1965): This combined federal and state program provides access to care for the poor and medically needy of all ages. Each state is allocated federal dollars on a matching basis (i.e., 50% of costs are paid with federal dollars). Each state has the responsibility and right to determine services to be provided and the dollar amount allocated to the program. Basic services (i.e., ambulatory and inpatient hospital care, physical therapy, laboratory, radiography, skilled nursing, and home health care) are required to be eligible for matching federal dollars. States may choose from a wide range of optional services including drugs, eyeglasses, intermediate care, inpatient psychiatric care, and dental care. Limits are placed on the amount and duration of service. Unlike Medicare, Medicaid provides long-term care services (e.g., nursing home and home health) and personal care services (e.g., chores and homemaking). In addition, Medicaid has eligibility criteria based on level of income. Table 10-2 provides the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) poverty guidelines for 2009. The Medicaid population has complex needs, and managed care organizations may not be able to provide optimum services to these beneficiaries. See Chapter 11 for more information on Medicaid.

• Public Health Act of 1944: The Public Health Act consolidated all existing public health legislation into one law. Since then, many new pieces of legislation have become amendments. Examples of some of its provisions, either in the original law or in amendments, provided for or established the following:

• Health services for migratory workers

• National Institutes of Health (NIH)

• Traineeships for graduate students in public health

• Home health services for people with Alzheimer’s disease

• Prevention and primary care services

• Communicable disease control

• McCarren-Ferguson Act of 1945: The McCarren-Ferguson Act has had a major influence on the insurance industry by giving states the exclusive right to regulate health insurance plans (Knight, 1998). No federal government agency is solely responsible for monitoring insurance. Some federal agencies are involved in insurance reimbursement; however, the structure of the benefit program for federal employees and military personnel, Medicare, and Medicaid allows Congress to pass laws that can override state laws if the laws meet certain criteria.

• Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970: The Occupational Safety and Health Act focuses on the health needs and risks in the workplace and environment. It continues to provide critical programs important to the workplace and the community. See Chapter 30 for more information on both the Occupational Safety and Health Act and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

• Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982: The Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act was a major amendment to the Social Security Act of 1935, establishing the prospective payment system (PPS) for Medicare, the diagnosis-related group (DRG) system. This law changed health care radically by introducing a new reimbursement method. See Chapter 11 for more information on DRGs.

• Welfare Reform Act of 1996: The Welfare Reform Act placed restrictions on eligibility for AFDC, Medicaid, and other federally funded welfare programs. This law decreased the number of people on welfare and forced many individuals to take low-paying jobs, many of which do not offer health insurance. Between 1994 and March 1999, welfare rolls dropped 47% (DeParle, 1999). Many individuals, particularly underserved women and children, subsequently lost Medicaid coverage.

• Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010: The Health Care Reform Act is an extremely complex and comprehensive piece of legislation. One of the primary intents of the act is to reduce the number of uninsured Americans, and a number of provisions directly address this intent. For example, it requires all U.S. citizens and legal residents to have qualifying health coverage, either provided through employers, individually purchased, or provided by federal plans (i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, CHIPS). It also dramatically changes eligibility requirements for Medicaid, allowing coverage of childless adults with incomes up to 133% of the federal poverty line and expands CHIPS. Further, it subsidizes premiums for lower and middle income families, and requires coverage of dependent adult children up to age 26 for those with group policies (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010).

TABLE 10-2

2009 Usdhhs Poverty Guidelines

| Persons in Family or Household | 48 Contiguous States and D.C. | Alaska | Hawaii |

| 1 | $10,830 | $13,540 | $12,460 |

| 2 | $14,570 | $18,220 | $16,760 |

| 3 | $18,310 | $22,890 | $21,060 |

| 4 | $22,050 | $27,570 | $25,360 |

| 5 | $25,790 | $32,240 | $29,660 |

| 6 | $29,530 | $36,920 | $33,960 |

| 7 | $33,270 | $41,590 | $38,260 |

| 8 | $37,010 | $46,270 | $42,570 |

| For each additional person, add | $3,740 | $4,680 | $4,300 |

From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Computations for the 2009 annual update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines for the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia, 2009: aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/09poverty.shtml.

Until passage of the Health Care Reform Act in 2010, the thrust of federal legislation has been on either prevention of illness through influencing the environment (e.g., Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970) or provision of funding to support programs that influence health care (e.g., Social Security Act of 1935). Beginning with the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921 and continuing to the present, federal grants have increased the involvement of state and local governments in health care. The involvement of the federal government through fiscal allocations to state and local governments provided money for programs not previously available to state and local areas. Similar services became available in all states. Funds supporting these services were accompanied by regulations that applied to all recipients. Many state and local government programs were developed on the basis of availability of federal funds. The involvement of the federal government through funding has served to standardize the public health policy in the United States (Pickett and Hanlon, 1990).

The rising number of uninsured and underinsured strongly influenced passage of the Health Reform Act of 2010, and although it is anticipated that about 32 million additional citizens will have insurance, universal coverage continues to be a concern. As mentioned, it will take a number of years to fully implement the act and the long-term effects will not be known for at least a decade. Further, legal and legislative challenges to some provisions are anticipated.

State Legislative Role

State governments are also directly involved in health care policy, legislation, and regulation. State governments focus particularly on financing and delivery of services and oversight of insurance. The latter has become important as managed care has grown. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) (1988) report Future of Public Health noted that it is the state’s responsibility to see that functions and services necessary to address the mission of public health are in place throughout the state. The IOM framed the public health enterprise in terms of three functions: assessment, policy development, and assurance. The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) (2007) described the “public health duties of states” and expanded on the three core functions of public health as the basis. The state health care functions are as follows (p. 7):

Legislation Influencing Managed Care

Prior to passage of the Health Care Reform Act in 2010, much of the recent legislation (i.e., usually state level) influencing managed care organizations (MCOs) is in response to consumers’ concerns about MCOs’ efforts to control costs. Considerable variability exists across states in MCO legislation, and usually these acts are in response to consumer calls for reform (Levy, 2002). The following examples describe a growing number of legislative acts that provide more control over managed care:

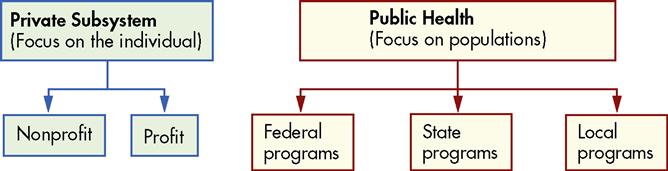

Components of the health care system

The current health care system consists of private and public health care subsystems (Figure 10-1). The private health care subsystem includes personal care services from various sources, both nonprofit and profit, and numerous voluntary agencies. The major focus of the public health subsystem is prevention of disease and illness. These subsystems are not always mutually exclusive, and their functions sometimes overlap.

With the rapid growth of technology and increased demands on the private and public health care subsystems, health care costs have become prohibitive. Cost-effectiveness and cost containment have become a critical driving force as health care delivery system changes are made, and cost-effectiveness often conflicts with the provision of quality care.

Community health nursing requires an understanding of the mission, organization, and role of the private and the public health care subsystems and the contexts within which they function to effectively collaborate with health care organizations to reach community health goals. An organizational framework in which private and voluntary organizations and the government work collaboratively to prevent disease and promote health is essential. Public health and community health nurses are in a unique position to provide leadership and facilitate change in the health care system.

Private Health Care Subsystem

Most personal health care services are provided in the private sector. Services in the private subsystem include health promotion, prevention and early detection of disease, diagnosis and treatment of disease with a focus on cure, rehabilitative-restorative care, and custodial care. These services are provided in clinics, physicians’ offices, hospitals, hospital ambulatory centers, skilled care facilities, and homes. Increasingly, these private sector services are available through MCOs.

Private health care services in the United States began with a simple model. Physicians provided care in their offices and made home visits. Clients were admitted to hospitals for general care if they experienced serious complications during the course of their illness. Currently, a variety of highly skilled health care professionals provide comprehensive, preventive, restorative, rehabilitative, and palliative care. A broad array of services is available, which range from general to highly specialized with multidelivery configurations.

Personal care provided by physicians is delivered under the following five basic models:

1. The solo practice of a physician in an office continues to be present in some communities.

3. Multispecialty group practice provides for interaction across specialty areas.

4. The integrated health maintenance model has prepaid multispecialty physicians.

Managed care has become the dominant paradigm in health care, affecting many aspects of health care delivery. Managed care involves capitated payments for care rather than fee- for-service. Health care providers, including physicians, hospitals, community clinics, and home care providers, are integrated in a system such as an HMO. See Chapter 11 for a more detailed discussion of managed care and reimbursement.

Voluntary Agencies

Voluntary or nonofficial agencies are a part of the private health care system of the United States and developed at the same time that the government was assuming responsibility for public health. In the United States during the 1700s and early 1800s, voluntary efforts to improve health were virtually nonexistent because early settlers from Western Europe were not accustomed to participating in organized charity. Immigration expanded to include slaves from Africa and people from Eastern Europe, and their well-being received little attention.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, new immigrants brought a heritage of social protest and reform. Wealthy businesspeople, such as the Rockefellers, Carnegies, and Mellons, responded to the needs and set up foundations that provided health and welfare money for charitable endeavors. District nurses, such as Lillian Wald, established nursing practices in the large cities for the poor and destitute. Services did not focus just on illness but also on work conditions, health, communicable diseases, living conditions, and language skills.

Voluntary agencies can be classified into the following categories (Hanlon and Pickett, 1990):

2. Organ or body structures, such as the National Kidney Foundation or the American Heart Association

3. Health and welfare of special groups, such as the National Council on Aging or the March of Dimes

4. Particular phases of health, such as the Planned Parenthood Federation of America

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree