Theris A. Touhy

Elimination

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

“UI (urinary incontinence) is like being a bad kid or a big baby.”

“There’s nothing that can be done. Well, I don’t think there is anything else but a diaper.”

“Sometimes I have to wet my bed before they get here, you know, and they are all busy and I have to wait for somebody, then I can’t control it.”

“I do something that is very wrong. I try not to drink too much but that’s so wrong. So how can you drink a lot, you would be soaked all the time.”

Comments from participants in a study of living with urinary incontinence in long-term care (MacDonald & Butler, 2007).

UI is a preventable and treatable condition and yet, “continence remains undervalued and UI remains underassessed. Even though UI is a basic nursing issue, nurses are not claiming it as one.”

Comment from nurses in expert continence care (Mason et al., 2003, p. 3).

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Define urinary and fecal incontinence.

• List factors contributing to urinary and fecal incontinence.

• Explain the types of urinary incontinence and their causes.

Glossary

Detrusor A body part that pushes down, such as the bladder muscle

Incontinence The inability to control excretory function

Micturition Urination

Transient Temporary

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Elimination

The body must remove waste products of metabolism to sustain healthy function, but bladder and bowel activity are fraught with social implications. Bladder and bowel function in later life, although normally only slightly altered by the physiological changes of age, can contribute to problems severe enough to interfere with the ability to continue independent living and can seriously threaten the body’s capacity to function and to survive. The effects of uncontrolled bladder and bowel action are a threat to the person’s independence and well-being. Elimination is a private matter, not publicized socially. As children, correct behavior in dealing with our own body waste is taught early. Deviations from this are socially unacceptable and can lead to chastisement, ostracism, and social withdrawal. Nurses are in a key position to implement evidence-based assessment and interventions to enhance continence and improve function, independence, and quality of life for older people.

Bladder function

Normal bladder function requires an intact brain and spinal cord, competent lower urinary tract function, the motivation to maintain continence, the functional ability to use a toilet, and an environment that facilitates the process. A full bladder increases pressure and signals the spinal cord and the brainstem center of the desire to micturate. Social training then dictates whether micturition should be attended to or should be postponed until there is an appropriate opportunity to seek out toilet facilities. However, when the bladder contents reach 500 mL or more, the pressure is such that it becomes more difficult to control the urge to void. As volume increases, emptying the bladder becomes an uncontrollable act.

Age-related changes

Bladder changes with aging include decreased capacity, increased irritability, contractions during filling, and incomplete emptying. In about 10% to 20% of well older adults, aging of the urinary tract is associated with an increased frequency of involuntary bladder contractions (Ham et al., 2007). These changes may lead to frequency, nocturia, urgency, and vulnerability to infection. The warning period between the desire to void and actual micturition is shortened. Postvoid residual urine volume increases to 75 to 100 mL in some cases. The first urge to void occurs at a lower bladder volume (150 to 300 mL) and total bladder capacity decreases to 300 to 600 mL (Ham et al., 2007). In combination with age-related changes, illness, cognitive impairments, difficulty in walking to the toilet or in handling a bedpan or urinal, and problems in manipulating clothing can affect an older person’s ability to maintain continence. Drugs that increase urinary output and sedatives, tranquilizers, and hypnotics, which produce drowsiness, confusion, or limited mobility, promote incontinence by dulling the transmission of the desire to urinate.

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI) is the involuntary loss of urine sufficient to be a problem (Dowling-Castronovo, 2008; Dowling-Castronovo & Bradway, 2012). UI is an important yet neglected geriatric syndrome. Because of the high prevalence and chronic but preventable nature of UI, it is most appropriately considered a public health problem (Lawthorne et al., 2008). UI is also a costly health problem with estimates that about 19.5 billion dollars are spent on UI care each year.

UI is a stigmatized, underreported, underdiagnosed, undertreated condition that is erroneously thought to be part of normal aging. About half of persons with UI have never discussed the concern with their primary care provider, and only one in eight who has experienced bladder control problems has been diagnosed. On average, women wait 6.5 years from the first time they experience symptoms until they obtain a diagnosis for their bladder control problems (Muller, 2005).

Individuals may not seek treatment for UI because they are embarrassed to talk about the problem or think that it is a normal part of aging. They may be unaware that successful treatments are available. Men may be unlikely to report UI to their primary care provider because they feel it is a woman’s disease. Further research is necessary to explore the prevalence and experience of UI in men. A guideline for UI in men can be found in the Evidence-Based Practice box. Older people want more information about bladder control, and nurses must take the lead in implementing approaches to continence promotion and public health education about UI (Palmer & Newman, 2006).

Without an adequate knowledge base of continence care and use of evidence-based practice guidelines, nursing care will continue to consist of containment strategies, such as the use of pads and briefs, to manage UI (Dowling-Castronovo & Spiro, 2008). UI tends to be viewed as an inconvenience rather than a condition requiring assessment and treatment (MacDonald & Butler, 2007). Nurses in all practice settings with older adults should be prepared to assess data that relate to urine control and implement nursing interventions that promote continence (Dowling-Castronovo & Bradway, 2012). There is a growing role for nurses in continence care and advanced training and certification are available through specialty organizations such as the Society of Urologic Nurses and Associates (www.suna.org) and the Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society (www.wocncb.org).

Prevalence of UI

UI affects millions of adults worldwide. Of those who experience UI, 75% to 80% are female; the prevalence of UI increases with age and functional dependency. Twenty-five percent of young women, 44% to 57% of middle-aged and postmenopausal women, and 75% of older women in nursing homes experience some involuntary urine loss (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2012). Some evidence suggests that European American women have higher rates of moderate and severe UI compared with African American and Asian women (Dowling-Castronovo & Bradway, 2012; Townsend et al., 2011).

Risk factors for UI

Cognitive impairment, limitations in daily activities, and institutionalization are associated with higher risks of UI. Stroke, diabetes, obesity, poor general health, and comorbidities are also associated with UI (Shamliyan et al., 2007). Pregnancy, childbirth, menopause, and hysterectomy are other factors that contribute to UI. Older people with dementia are at high risk for UI. Hospital patients with dementia are more likely than other older people to develop new incontinence.

Dementia does not cause urinary incontinence but affects the ability of the person to find a bathroom and recognize the urge to void. Mobility problems and dependency in transfers are better predictors of continence status than dementia, suggesting that persons with dementia may have the potential to remain continent as long as they are mobile. Making toilets easily visible, providing assistance to the bathroom at regular intervals, and implementing prompted voiding protocols can assist in continence promotion for people with dementia. Box 10-1 presents risk factors for UI.

Consequences of UI

UI is identified as a marker of frailty in community-dwelling older adults. UI is associated with falls, skin irritations and infections, urinary tract infections (UTIs), pressure ulcers, and sleep disturbance. UI affects self-esteem and increases the risk for depression, anxiety, social isolation, and avoidance of sexual activity. Older adults with UI experience a loss of dignity, independence, and self-confidence, as well as feelings of shame and embarrassment (MacDonald & Butler, 2007; Dowling-Castronovo & Spiro, 2008). The psychosocial impact of UI affects the individual as well as the family caregivers.

Types of UI

Incontinence is classified as either transient (acute) or established (chronic). Transient incontinence has a sudden onset, is present for 6 months or less, and is usually caused by treatable factors such as UTIs, delirium, constipation and stool impaction, and increased urine production caused by metabolic conditions such as hyperglycemia and hypercalcemia. Iatrogenic (or treatment-induced) incontinence is a type of transient UI that results from the use of restraints, limited fluid intake, bed rest, or intravenous fluid administration. Use of medications such as diuretics, anticholinergic agents, antidepressants, sedatives, hypnotics, calcium channel blockers, and α-adrenergic agonists and blockers can also lead to transient UI (Dowling-Castronovo & Bradway, 2012).

Established UI may have either a sudden or gradual onset and is categorized into the following types: (1) urge; (2) stress; (3) urge, mixed, or stress UI with high postvoid residual (originally termed overflow UI); (4) functional UI; and (5) mixed UI.

Urge incontinence (overactive bladder) is defined as involuntary urine loss that occurs soon after feeling an urgent need to void. Overactive bladder is a syndrome that overlaps with urge UI. With overactive bladder syndrome, individuals have urinary frequency (more than eight voids in 24 hours), nocturia, urgency, with or without incontinence (Zarowitz & Ouslander, 2007). The bladder muscles are overactive and cause a sudden urge to void—the “Gotta Go Right Now” syndrome (Bucci, 2007). Defining characteristics of urge UI include loss of urine in moderate to large amounts before getting to the toilet and an inability to suppress the need to urinate. Postvoid residual urine reveals a low volume. Urge UI is the most common type of urinary incontinence in older adults.

Stress incontinence (outlet incompetence) is defined as an involuntary loss of less than 50 mL of urine associated with activities that increase intraabdominal pressure (e.g., coughing, sneezing, exercise, lifting, bending). Stress UI is more common in women because of short urethras and poor pelvic muscle tone. Stress UI occurs in men who have experienced prostatectomy and radiation. Postvoid residual urine is low.

Urge, mixed, or stress UI with high postvoid residual incontinence (formerly called overflow UI) occurs when the bladder does not empty normally and becomes overdistended with frequent and nearly constant urine loss (dribbling). Other symptoms include hesitancy in starting urination, slow urine stream, passage of infrequent or small volumes of urine, a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, and large postvoid residuals. Persons with diabetes and men with enlarged prostates are at risk for this type of UI. Calcium channel blockers, anticholinergics, and adrenergics also contribute to symptoms.

Functional incontinence refers to a situation in which the lower urinary tract is intact but the individual is unable to reach the toilet because of environmental barriers, physical limitations, or severe cognitive impairment. Individuals may be dependent on others for assistance to the toilet but have no genitourinary problems other than incontinence. Older adults who are institutionalized have higher rates of functional incontinence (Dowling-Castronovo & Bradway, 2012). Functional UI may also occur in the presence of other types of UI.

Mixed incontinence is a combination of more than one urinary incontinence problem, usually stress and urge. Mixed UI is the most prevalent type of UI in women, and with increasing age older women with stress UI begin to experience urge UI (Shamliyan et al., 2007).

Implications for gerontological nursing and healthy aging

Assessment

Continence must be routinely addressed in the initial assessment of every older person, yet many older people do not bring up their concerns about incontinence, and many health professionals do not ask. Health care personnel must begin to change their thinking about incontinence and acknowledge that incontinence can be cured. If it cannot be cured, it can be treated to minimize its detrimental effects. Nurses are often the ones to identify urinary incontinence, but neither nurses nor physicians have been particularly aggressive in its management. “Nurses have long been the providers of personal hygiene information for those entrusted to their care. Therefore, it is essential that nurses play a leading role in assessing and managing UI . . .” (Dowling-Castronovo & Bradway, 2007, p. 7).

To begin the assessment, screening questions such as “Have you ever leaked urine? If yes, how much does it bother you?” are suggested (Dowling-Castronovo & Bradway, 2007). Assessment is multidimensional. It includes a health history, targeted physical examination (abdominal, rectal, genital), urinalysis, and determination of postvoid residual urine. For women, evaluation of the reproductive system and gynecological history and examination is recommended since gynecological factors may contribute to the urological problem. More extensive examinations are considered after the initial findings are assessed. Individuals who do not fit a simple pattern on UI should be referred promptly for urodynamic assessment (Ham et al., 2007).

A thorough health history should focus on the medical, neurological, gynecological, and genitourinary history. It should include functional assessment, cognitive assessment, psychosocial effects; strategies currently used to control UI; a medication review of both prescribed and over-the-counter drugs; a detailed exploration of the symptoms of the urinary incontinence; and associated symptoms and other factors. In care facilities, an environmental assessment including the accessibility of bathrooms, room lighting, and the use of aids such as raised toilet seats or commodes is also important. A link to a video of a nurse performing an assessment to evaluate transient incontinence can be found in the Evidence-Based Practice box.

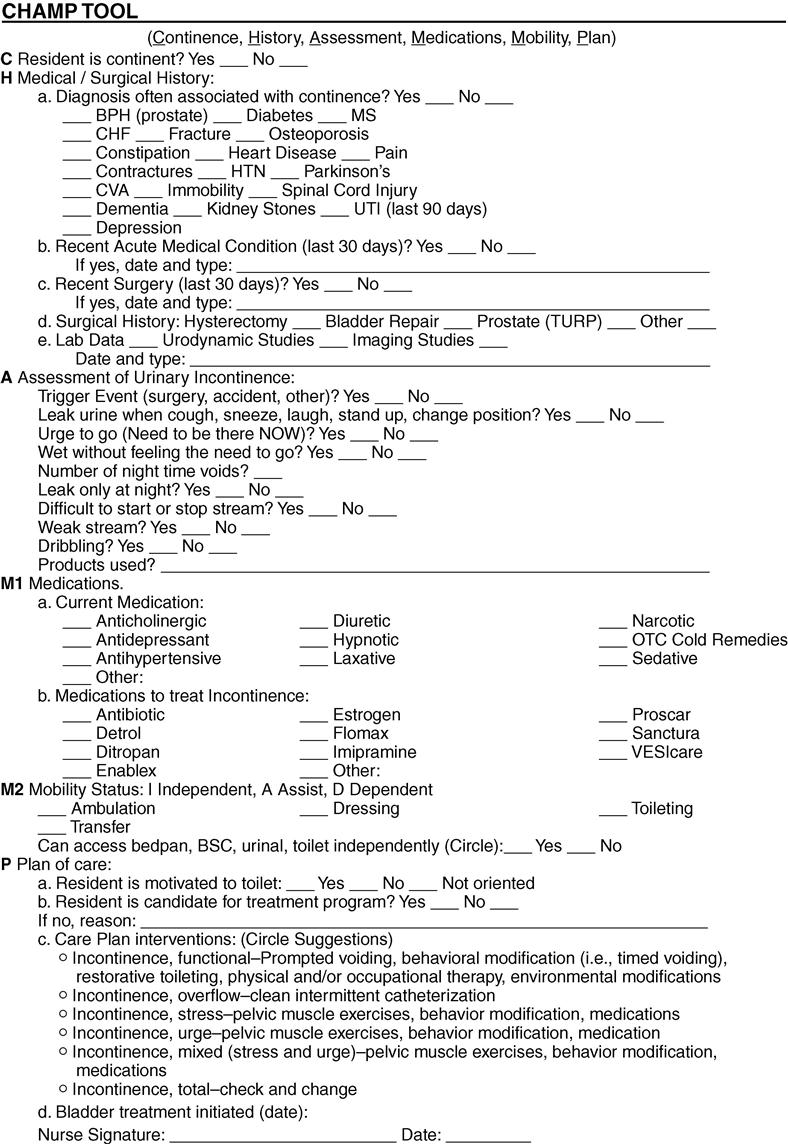

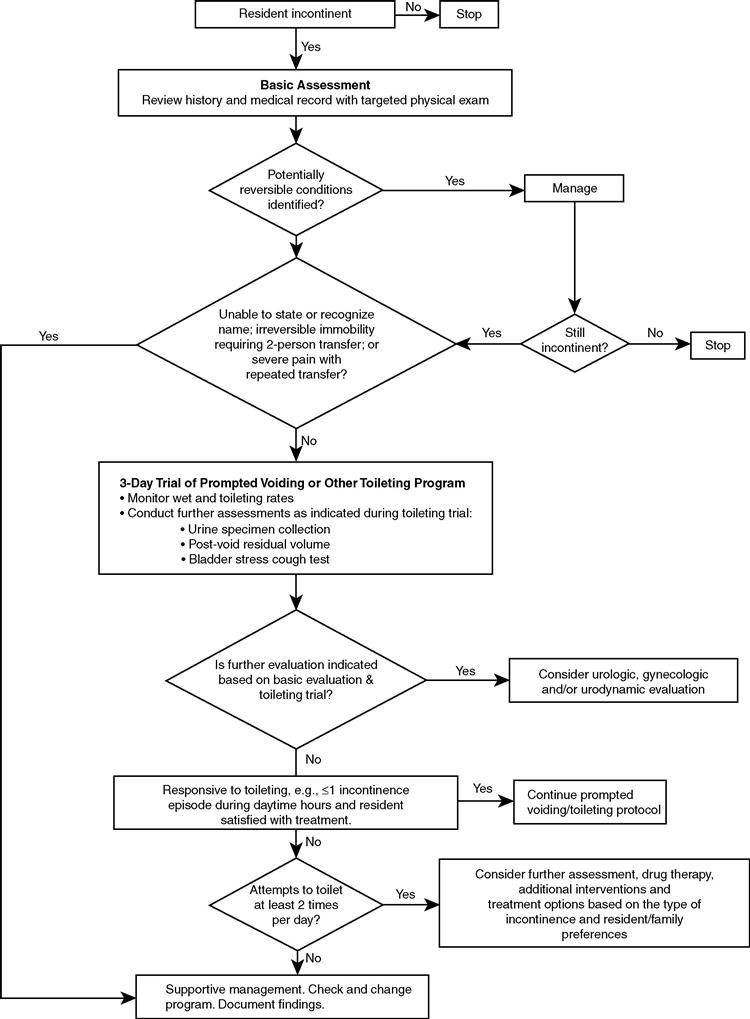

In the nursing home, continence is assessed with the Minimum Data Set 3.0 (MDS) which provides a comprehensive overview of the assessment, treatment, and evaluation of bladder and bowel continence based on the new Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) guidelines (Johnson & Ouslander, 2006). All newly admitted nursing home residents should have a thorough assessment of continence status as well as ongoing evaluations during their length of stay (Figure 10-1). Both acute and long-term care facilities should perform comprehensive assessments of continence. Figure 10-2 presents a guide for the diagnostic assessment and management of UI in the nursing home setting.

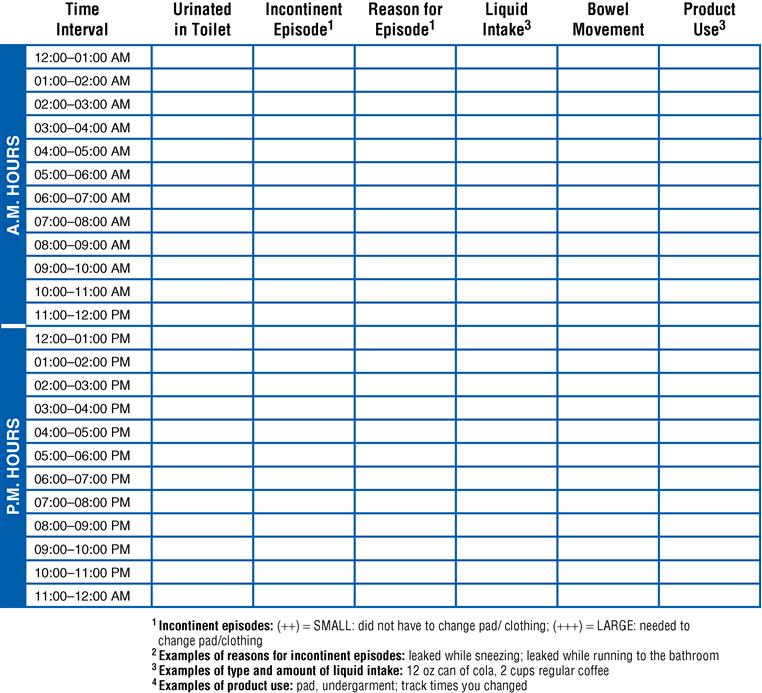

One of the best ways to establish the presence of and describe incontinence problems is with a voiding diary. This is considered the “gold standard” for obtaining objective information about the person’s voiding patterns and the UI episodes and their severity (Dowling-Castronovo & Bradway, 2007, p. 314) (Figure 10-3). The voiding diary can be used by both community-dwelling and institutionalized elders. The character of the urine (color, odor, sediment, or clear) and difficulty starting or stopping the urinary stream should be recorded. Activities of daily living (ADLs), such as ability to reach a toilet and use it and finger dexterity for clothing manipulation, should be documented.

Interventions

Behavioral

Urinary incontinence can be improved when appropriate care is provided. A number of behavioral interventions have a good basis in research and can be implemented by nurses without extensive and expensive evaluation. These treatments are viewed as healthy bladder behavior skills (HBBSs) (Dowling-Castronovo & Bradway, 2012). These interventions will do no harm and if there is no improvement, further evaluation can be sought. Before instituting HBBSs, the nurse should assess the motivation of the patient, informal caregiver, and/or nursing staff because behavior management is the premise of HBBSs. Behavioral techniques, such as scheduled voiding, prompted voiding, bladder training, biofeedback, and pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFMEs), are recommended as first-line treatment of UI.

Selection of a modality and interventions will depend on a comprehensive assessment, the type of incontinence and its underlying cause, and whether the outcome is to cure or to minimize the extent of the incontinence. Interventions for UI should be multidisciplinary, and everyone involved with the person’s care should be involved in the treatment plan. If the person has mobility impairments, physical and occupational therapy and/or restorative nursing programs should be implemented as part of the treatment plan for UI. Box 10-2 lists the numerous modalities available in the treatment of incontinence. Nursing interventions focus primarily on the appropriate assessment of continence and implementation and evaluation of supportive and therapeutic modalities to promote and restore continence and to prevent incontinence-related complications, such as skin breakdown.