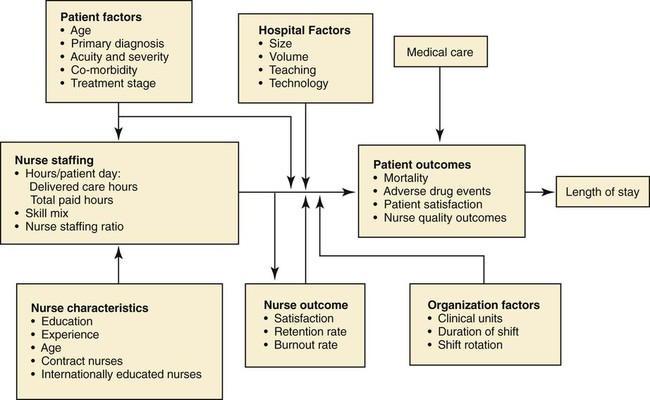

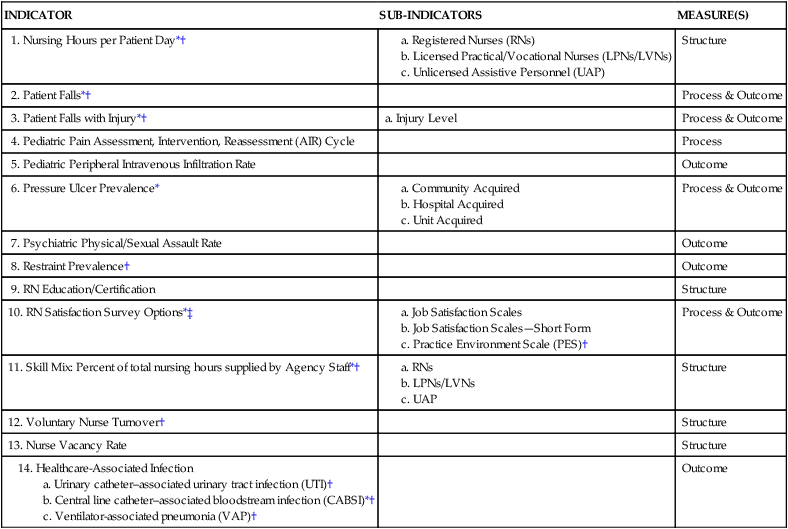

• Evaluate the impact of patient and hospital factors, nurse characteristics, nurse staffing, and other organizational factors that influence nurse and patient outcomes. • Integrate current research into principles to effectively manage nurse staffing. • Analyze activity reports to determine the effectiveness of a unit’s productivity. • Examine personal scheduling needs in relation to patients’ requirements for continuity of care and positive outcomes, as well as the nurse manager’s need to create a schedule that is balanced and fair for all team members. • Relate floating, mandatory overtime, and the use of supplemental agency staff to nurse satisfaction and patient care outcomes. Because of the emphasis on patient safety and ensuring positive patient outcomes in health care, research to define the “best practices” of staffing has been a high priority in the past 15 years. Consistently over that period, the research suggests that increasing the numbers of registered nurses results in many positive benefits to patients, such as a reduction in hospital-related mortality and failure to rescue, both nurses-sensitive outcomes (Kane, Shamliyan, Mueller, Duval, & Wilt, 2007). None of these studies demonstrated a causal relationship. Further, hospitals with an overall commitment to high-quality care through sufficient staffing also invested in other actions that improve quality (Kane et al., 2007). The results of the meta-analysis by Kane et al. (2007) is published in an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) report “Nursing Staffing and Quality of Patient Care” (www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tp/nursesttp.htm). Based on the relevant research, the authors developed a conceptual framework (Figure 14-1) illustrating the complex relationships between nurse staffing and the quality of patient care. The framework considers the impact of patient and hospital factors, nurse staffing, nurse characteristics, nurse outcomes, medical care, and organizational factors on patient outcomes. Hyun, Bakken, Douglas, and Stone (2008) suggest that although data available to decide how to effectively allocate scarce nursing resources in practice are still limited, existing principles, frameworks, and guidelines provide a foundation for evidence-based nurse staffing. So, despite the complex relationships apparent in the AHRQ framework, it can be useful not only for further research but also for nurse managers to develop “best practices” for staffing. The NDNQI® (www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ThePracticeofProfessionalNursing/PatientSafetyQuality.aspx) is the only national nursing database that provides quarterly and annual reporting of structure, process, and outcome indicators to evaluate nursing care at the unit level. This large, longitudinal database is built upon the 1994 American Nurses Association (ANA) Patient Safety and Quality Initiative. This initiative involved a series of pilot studies across the United States to identify nurse-sensitive indicators to use in evaluating patient care quality. These nurse-sensitive indicators include both structures of care and care processes, which in turn influence care outcomes. Nurse-sensitive indicators are distinct and specific to nursing and different from medical indicators of care quality (Montalvo, 2009). Data for the NDNQI® database are collected for eight types of units: critical care, step-down, medical, surgical, combined medical-surgical, rehabilitation, pediatric, and psychiatric. RN survey data are collected for all hospital unit types including outpatient and interventional units (Dunton, Gajewski, Klaus, & Pierson, 2007). Hospitals may join the NDNQI® project, submitting data regarding nurse-sensitive indicators. Hospitals can benchmark (or compare) their own data against other similar hospitals and participate in the ongoing research on nurse-sensitive data. Table 14-1 outlines the nurse-sensitive indicators included in the NDNQI® project. TABLE 14-1 NURSE-SENSITIVE INDICATORS INCLUDED IN THE NDNQI® PROJECT *Original American Nurses Association (ANA) nursing-sensitive indicator. †National Quality Forum (NQF)–endorsed nursing-sensitive indicator “NQF-15.” ‡The RN survey is annual, whereas the other indicators are quarterly. From Montalvo, I. (September 2007). The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators™ (NDNQI®). OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 12(3), 2. A component of the NDNQI® database is the hours per patient day (HPPD) required to provide the necessary care for patients on the unit. This figure may include the HPPD of total nursing care provided or the HPPD of RN care provided. The NDNQI® project reports a number of findings related to the HPPD required by patients. For example, Dunton, et al. (2007) suggest that: • Lower falls rates were related to higher total nursing hours (including RN, licensed practical nurse/licensed vocational nurse [LPN/LVN] and unlicensed nursing assistants) per patient day and a higher percentage of nursing hours supplied by RNs. • For every increase of 1 hour in total nursing HPPD, fall rates were 1.9% lower. • For every increase of 1 percentage point in the nursing hours supplied by RNs, the fall rate was 0.7% lower (Dunton et al., 2007). Nurse managers may also use clinical or human resource indicators other than those identified by NDNQI® to evaluate the effectiveness of the staffing and quality of patient care. Box 14-1 identifies some of these indicators. Over the past 10 years, as the evidence regarding nurse-sensitive indicators has grown, there has been significant controversy regarding the level of nurse staff required for various groups of patients, primarily in acute care hospitals. In 2008, the ANA polled more than 10,000 nurses nationally to determine their perceptions of the impact of staffing levels on their work environment. Of the nurse respondents, 73% did not believe the staffing on their unit or shift was sufficient and 59.8% said they knew of someone who left direct care because of concerns about safe staffing. Of the 51.9% of respondents who were considering leaving their current position, 46% cited inadequate staffing as the reason. Almost 52% of the respondents said that they thought the quality of nursing care on their unit had declined in the past year, and 48.2% would not feel confident having someone close to them receiving care in the facility where they work (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2008). The recognition that the number of nurses providing care to patients is associated with better patient outcomes in acute care leads to a discussion regarding the best model to ensure sufficient staffing. Two major approaches have been put forward. The first requires a specific number of patients cared for by one nurse per shift (mandated nurse-patient ratios). Legislation to mandate specific nurse-patient ratios was implemented in California in 1999 (Keepnews, 2007). The second approach requires the development of a staffing plan, which holds hospitals accountable for projecting the nursing needs on each unit for a period of time, typically for 6 months or a year. Hospitals are also responsible for monitoring the extent to which actual staffing matches the staffing plans, making revisions as necessary. These plans often require that direct care nurses are part of the nurse staffing committee to ensure that safe nurse-to-patient ratios are based on patient needs and other related criteria. The first legislation mandating such a committee was passed by the Texas state legislature in 2002. As of October 2008, seven states had some sort of legislation requiring a nursing staffing plan in acute care hospitals (Haebler, 2008). Those who support a specified nurse-patient ratio based on the type of unit (e.g., ICU, medical-surgical) believe this approach will require hospitals to either find sufficient numbers of nurses to meet the ratio or shut down units. Those who prefer the nurse staffing plan approach believe that use of a staffing plan is built on nursing judgment that will allow staffing to be flexible, depending on patient acuity, nurse experience, configuration of the unit, and other factors. The ANA has developed a website (http://safestaffingsaveslives.org/) devoted specifically to staffing. This website, Safe Staffing Saves Lives, includes the principles of safe staffing developed by ANA that apply to all clinical care settings (Box 14-2). Review the website for more information. Most of the research regarding safe staffing has been done in acute care hospitals or long-term care facilities. As a result, these findings must be applied to other healthcare settings with some caution. In addition, there has been little research regarding the differences in staffing in any clinical environment during off-peak hours (nights and weekends). Despite the fact that hospital activity is at its peak from 7 am to 7 pm weekdays, when maximum resources are available in the nurse’s work environment, this time represents only 36% of the time that nurses work in acute care or long-term care. During the remaining 64% of the time, nurses work in off-peak environments with (1) scaled-back ancillary personnel, (2) fewer (often less-experienced) staff, (3) minimal supervision, and (4) strained communication with on-call healthcare providers (Hamilton, Eschiti, Hernandez, & Neill, 2007). The problems identified by Hamilton et al. (2007) are corroborated in other studies. Researchers have associated weekends and nights with increased mortality in hospitals for more than 25 diagnoses/patient groups. For example, Becker (2007) found acute myocardial infarction more likely to result in death among Medicaid patients admitted on weekends and Goldfarb and Rowan (2000) reported mortality after night discharge from ICU to a general unit to be 2.5 times greater compared with discharge during the day. Peberdy et al. (2008) found lower survival rates from inpatient cardiology units at nights and on weekends, even after adjusting for potentially confounding factors. Although the reasons for the differences in risk in off-peak hours are under investigation, nurse managers must be cognizant of these differences and staff during off-peak times in a prudent manner to minimize patient risk.

Staffing and Scheduling

The Staffing Process

AHRQ Nurse Staffing Model

Patient Factors

National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators®

INDICATOR

SUB-INDICATORS

MEASURE(S)

1. Nursing Hours per Patient Day*†

Structure

2. Patient Falls*†

Process & Outcome

3. Patient Falls with Injury*†

a. Injury Level

Process & Outcome

4. Pediatric Pain Assessment, Intervention, Reassessment (AIR) Cycle

Process

5. Pediatric Peripheral Intravenous Infiltration Rate

Outcome

6. Pressure Ulcer Prevalence*

Process & Outcome

7. Psychiatric Physical/Sexual Assault Rate

Outcome

8. Restraint Prevalence†

Outcome

9. RN Education/Certification

Structure

10. RN Satisfaction Survey Options*‡

Process & Outcome

11. Skill Mix: Percent of total nursing hours supplied by Agency Staff*†

Structure

12. Voluntary Nurse Turnover†

Structure

13. Nurse Vacancy Rate

Structure

Outcome

Nurse Staffing

24-Hour Staffing

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access