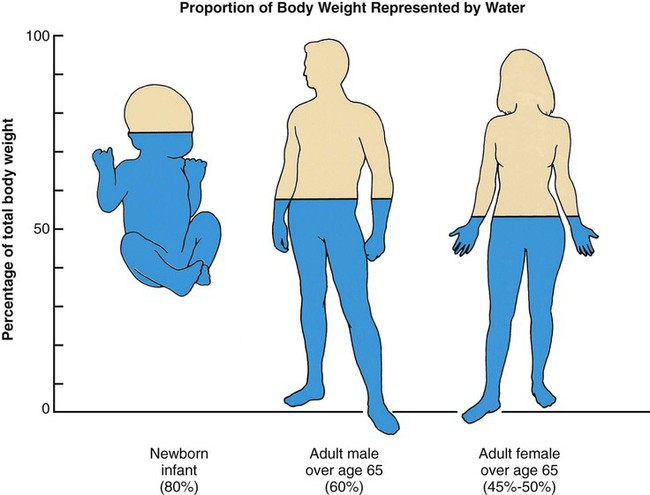

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Identify and discuss the normal age-related changes to the human physiological systems. 2. Begin to differentiate normal changes with aging from potentially pathological conditions. 3. Discuss the implications of the normal age-related changes on the promotion of healthy aging. 4. Identify nursing interventions that promote healthy physiological aging. Physiological changes with aging pick up speed in the 30s. By the 40s the changes begin to become noticeable; more so in the 50s and beyond. Although changes are occurring at the cellular level (see Chapter 3), external signs are the clues by which most people judge someone as “getting older.” This external appearance is an expression of one’s genetic make-up and epigenetic influence and is referred to as the “aging phenotype.” Several of the normal age-related changes are similar to those seen in the presence of pathological conditions. Differentiating these from those that are expected is sometimes difficult. Many internal changes mimic disease manifestations and might be interpreted as a pathological state in need of medical attention (Box 4-1). On the other hand, normal changes can mask early signs of potentially reversible disease processes, such as when the changes are incorrectly attributed to aging (Box 4-2). It is important for those who care for older adults to carefully explore the changes that do occur rather than immediately categorize them as either pathological or normal. Although normal age-related changes have usually been studied in concert with the most common pathological or disease conditions seen in late life, it is important for the gerontological nurse to be aware that they are not one and the same. The integument is the largest organ of the body (Figure 4-1). It provides clues to hereditary, dietary, physical, and emotional conditions and health. The skin serves as a means of communication and enables us to experience touch, warmth, cold, and pain. It protects the internal organs, helps regulate body temperature, serves as an efficient vehicle for the excretion of salts, water, and organic wastes, and stores fat. It helps protect the person from the damage of ultraviolet rays and produces vitamin D. Finally, the integument gives each person his or her unique and changing appearance. The integument is composed of the skin, hair, and nails. The skin is made up of three layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the underlying subcutaneous layers between the skin and the muscles. The age-related changes in skin, hair, and nails are obvious to others and may be the first things noticed and attributed to “old age.” Characteristic thinning, dryness, roughness, wrinkles, and lightening are to be expected. These changes may be of clinical significance, such as those altering the absorption of topical medications (see Chapter 9). Extrinsic causes of skin changes include environmental factors such as exposure to pollutants, chemicals, and solar radiation. Sun exposure, in particular, increases the extent and speed of the normal changes in aging skin. An increased incidence of skin cancer is usually the result of a lifetime of solar exposure. An increased number of allergic rashes, irritations, and infections is associated with lessened immunity. Intrinsic changes occur gradually over time and have been tied to the oxidation and cross-link theories of aging (see Chapter 3). The epithelium in a healthy young adult renews itself every 20 days, whereas epithelial renewal in an older adult may take 30% to 50% longer because the keratinocytes become smaller and regeneration slows (Saxon et al., 2010). This has significant implications for the slowed wound healing seen in the older adult. The number of melanocytes in the epidermis decreases about 10% to 20% per decade, resulting in lightening of the overall skin tone, regardless of original skin color, with a decrease in the amount of protection from ultraviolet rays (Saxon et al., 2010). Pigment spots (freckles and nevi) enlarge with age and can become more numerous with increased exposure to natural and artificial light. Lentigines, referred to as “age spots” or “liver spots,” are common in older, lighter skinned persons. They are frequently found on the backs of the hands, wrists, and faces of light-skinned persons older than 50 years. Thick, brown, raised lesions with a “stuck on” appearance (seborrheic keratosis) are also common (Figure 4-2). They are the most common benign tumors in older, lighter skinned individuals. In one study of 22 residents of the Orthodox Jewish Home for the Aged (Cincinnati, OH), seborrheic keratosis was found in 29.3% of the men and 37.9% of the women (Balin, 2009). Dermatosis papulosa nigra, a variant of keratosis in persons with darker skin, consists of multiple, firm, smooth, dark brown to black flattened papules 1 to 5 cm in diameter (Nowfar-Rad and Fish, 2009). Although they often begin in youth, they increase significantly with age and are clinically insignificant (Figure 4-3). The dermis loses about 20% of its thickness with aging (Saxon et al., 2010). The thinness of the dermis is what causes older skin to look more transparent and fragile. Dermal blood vessels are reduced, resulting in skin pallor and cooler skin temperature. Cross-linkage increases (see Chapter 3) and collagen synthesis decreases, causing the skin to “give” less under stress and to tear more easily. Elastin fibers, especially susceptible to cross-linking, thicken and fragment, leading to loss of stretch and resilience and a “sagging” appearance. The effect of changes in collagen and elastin can be found throughout the body, as is discussed below. Vascular hyperplasia causes more pronounced varicosities, benign cherry angiomas, and venous stars. Skin becomes dryer because of decreases in sebum production, and the risk for cracking and xerosis increases (see Chapter 11). Alteration in body weight occurs as lean mass declines and body water is lost with a concomitant higher risk for dehydration (Figure 4-4). Subcutaneous fat seems to “shift” locations with aging. Loss of fat around the orbit of the eye creates a sunken appearance. Landmarks become more prominent, and muscle contours are easily identified. Women older than 45 years begin to see the skinfolds on the back of their hands diminish, even if weight gain is substantial. At the same time, the amount of adipose tissue increases in the abdomen and, for women, in the thighs, even without a change in actual body weight. One study found that women’s waist circumference increased up to 5.7 cm in the 6 years surrounding menopause (Sowers et al., 2007). Despite the increase in adiposity, the ability to regulate temperature is diminished by a number of causes. The risk for hyperthermia is elevated with the reduced efficiency of the eccrine glands. They become fibrotic, and surrounding connective tissue becomes avascular, resulting in a decline in the body’s ability to cool itself through perspiration; there is an increased risk for heat exhaustion and heat stroke. There is also an increased risk for hypothermia. As sebaceous glands secrete less oil, moisture evaporates more readily. Windy, dry, cold weather can accelerate loss of body heat by evaporation (Cunningham and Brookbank, 1988). Changes in hair are sex-based. For men, vertex and frontal and temporal hair loss, or androgenic alopecia, may begin in the late teens or early 20s, and by 60 years of age 80% of men are substantially bald. The amount of hair increases in the ears, nose, and eyebrows (Saxon et al., 2010). Women may experience the same pattern of hair loss as men, but it is less pronounced. Their hair is more likely to become thinner overall and finer. Terminal hair can occur in the face and chin area after menopause with the altered balance of estrogen and androgens. For both men and women, axillary, extremity, and pubic hair diminishes and, in some instances, disappears. Absence of lower extremity hair may be misinterpreted as a sign of peripheral vascular disease. Race, gender, sex-linked genes, and hormonal balance influence the maximal amount of hair that one has and the changes that will occur throughout life. Persons of Asian descent are less hairy than white individuals, and Native Americans may have little or no body hair (Rossman, 1986). Due in part to decreased circulation, fingernails and toenails thicken, change shape and color. Nails become more brittle, flat or concave (rather than convex), with longitudinal striations. Nails may yellow or appear grayish with poorly defined or absent lunulae. Pigmented bands may appear in the nails of persons with darker skin tones and must be differentiated from melanoma. Brittle nails with splitting ends or layers commonly occur. The cuticle becomes less thick and wide. Vigorous manipulation of the cuticle, such as in manicures, may lead to slowed nail growth. Although not a normal part of aging, onychogryphosis (thickening and distortion of the nail plate) and the fungal infection onycholysis are common. Vertical ridges (onychorrhexis) may appear as a result of poor nutrition, microtrauma, and disease (Chiu, 2000). Although the nails need more careful attention, this may be less possible because of other changes, such as loss of close vision. See Box 4-3 for interventions that promote healthy skin and potential implications for gerontological nursing. Changes in stature and posture are two of the obvious outward signs of aging. They occur very gradually and are caused by multiple developmental factors involving skeletal, muscular, subcutaneous, and fat tissue. Vertebral disks become thin as a result of gravity and dehydration, causing a shortening of the trunk. When combined with a slight curving of the cervical vertebra, height is lost; loss of up to 3 inches is not uncommon. The long bones, which are not affected, take on the appearance of disproportionate size. A stooped, slightly forward-bent posture is common and may be accompanied by slightly flexed hips and knees and somewhat flexed arms, bent at the elbows. To maintain eye contact, it may be necessary to tilt the head backward, which makes it appear that the person is jutting forward. Posture and structural changes occur primarily because of age-related bone calcium loss and atrophic cartilage and muscle (Figure 4-5). Bones are composed of both organic tissue and inorganic products, especially minerals. Bone is a constantly changing tissue. There is ongoing and cyclic resorption (into the bloodstream) and renewal (into the bone) of minerals, especially calcium. With age, resorption is more rapid than renewal (Box 4-4). This results in reduced bone mineral density (BMD). Reduced BMD is four times more common in older women than in men. For women it is directly associated with hormonal changes following menopause, with the most rapid loss in the first 5 to 10 years. Women who are not taking hormone replacement may lose up to 50% of their cortical bone mass by the time they are 70 years old (Crowther-Radulewicz, 2010). In men, reduced BMD is primarily due to prolonged steroid use. Excessive loss of BMD leads to in osteopenia or osteoporosis (see Chapter 15). Osteoporosis of the cervical spine results in a C-shaped or kyphotic neck. Resorption of the bone in the mandible leads to poorly fitting dentures and painful sensations when chewing or biting. But by far the most important issue related to osteoporosis is the increased risk for fall-related fractures. See Chapter 12 for a detailed discussion related to falls. Age-related changes in articular cartilage result from biochemical changes: increases in transglutaminase and possibly calcium pyrophosphates. As the cartilage in the joint dries, it becomes thinner, and results in less fluidity of movement or pain as bone rubs on bone. With progressive loss of cartilage, the common pathological condition of osteoarthritis may develop (see Chapter 15). Cartilage in the nose and ears continues to grow throughout life, leading to a change in facial appearance in late life, especially for men. The three types of muscles are skeletal, smooth, and cardiac. Skeletal muscle is essential for movement, posture, and heat production; much of it is under voluntary control. Smooth muscle, under the control of the autonomic nervous system, is found throughout the body, primarily in the lining of the organs and blood vessels. Cardiac muscle is a special muscle found only in the heart. Muscle mass can continue to build until a person is in his or her 50s. However, between 30% and 40% of the skeletal muscle mass of a 30-year-old may be lost by the time the person is in his or her 90s (Crowther-Radulewicz, 2010). Suggested nursing interventions to promote healthy aging of bones and muscles can be found in Box 4-5. The cardiovascular system comprises the blood, the blood vessels, and the heart. The cardiovascular system is responsible for the transport of oxygen and nutrient-rich blood to the organs and the transport of metabolic waste products to the excretory organs. The most relevant age-related changes in this system are myocardial and blood vessel stiffening, decreased β-adrenoceptor responsiveness, impaired autonomic reflex control of the heart rate, left ventricular hypertrophy, and fibrosis (Brashers and McCance, 2010). In health, changes in the cardiovascular system are minimal and have little or no effect on its ability to function except when the need for blood flow is increased as in illness. However, the prevalence of cardiovascular disease, particularly heart disease, is so high that it is sometimes mistaken as normal in later life. Much heart disease is preventable (see Chapter 15). Electrocardiographic changes with aging under normal circumstances are minimal. PR, QRS, and QT intervals lengthen slightly. Catecholamines and certain enzymes that influence the force and speed of heart contractions diminish in concentration, resulting in a longer interval between contractions, weakened cardiac force, and a greater energy demand on heart muscle. Lower contractile strength, reduced cardiac output, and reduced enzymatic stimulation together cause the heart to respond to the work demand with less efficient performance and greater energy expenditure than would be required at a younger age (Brashers and McCance, 2010). During the third and fourth decades of life, and accelerating in the sixth decade, SA node cells decrease in number. The number of SA cells at age 75 years is only 10% of that which existed at age 20 years (Taffet and Lakatta, 2003). Similarly, the AV node and the bundle of His lose a number of conductive cells into the fourth decade, and the left bundle loses cells between the fifth and seventh decades (Saxon et al., 2010). The most significant age-related change is reduced elasticity. Elastin fibers fray, split, straighten, and fragment. While there is little change in flow to the coronary arteries or the brain, perfusion of other tissues and organs is reduced. Reductions in the perfusion of the liver and kidneys can be significant in relation to medication metabolism (see Chapter 9). Key points in promoting a healthy heart can be found in Box 4-6. The respiratory system is the vehicle for ventilation and gas exchange, particularly the transfer of oxygen into and the release of carbon dioxide from the blood. The respiratory structures depend on the musculoskeletal and nervous systems for full function. Like the cardiovascular system, in healthy aging only subtle changes occur in the respiratory system. The changes are seen in every component of each systems, including the lungs, thoracic cage, respiratory muscles, and respiratory centers in the central nervous system, and these changes are mostly insignificant. Specific age-related changes include loss of elastic recoil, stiffening of the chest wall, inefficiency in gas exchange, and increased resistance to air flow (Figure 4-6). Respiratory problems are common but are almost always attributed to exposure to environmental toxins (e.g., pollution, cigarette smoke) rather than the aging process itself (Sheahan and Musialowski, 2001). As with the cardiovascular system, the biggest change in the aging respiratory system is its lower efficiency, in this case of gas exchange and ability to handle secretions. Under normal conditions this has little or no effect on the performance of customary life activities. However, when an older individual is confronted with a sudden demand for increased oxygen or is exposed to noxious or infectious agents, a respiratory deficit may become evident and can be life-threatening (Table 4-1). TABLE 4-1 AGE-RELATED CHANGES IN THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

Physiological Changes

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/TwdHlthAging

The Integument

Skin

Epidermis

Dermis

Hypodermis

Thermoregulation

Hair

Nails

The Musculoskeletal System

Structure and Posture

These changes can cause a potential loss of as much as 6 to 9 inches in height. Note the exaggerated thoracic and lumbar curves at age 70 years. (From Ignatavicius DD, Workman ML: Medical-surgical nursing: patient centered collaborative care, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2010, WB Saunders. Data from Sattin RW, Easley KA, Wolf SL, et al: Reduction in fear of falling through intense tai chi exercise training in older, transitionally frail adults, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53:1168, 2005.)

Bones

Joints, Tendons, and Ligaments

Muscles

The Cardiovascular System

Heart

Conductivity

Blood Vessels

The Respiratory System

RESPIRATORY FUNCTION

PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Mechanics of breathing

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Physiological Changes

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access