Working Together: Collaboration, Coalition Building, and Community Organizing

Adrienne Wald

|

Public health nursing, being closely related to the activities of several other professions and many community organizations, cannot be carried on successfully and productively as an isolated service. The more closely it is coordinated with the interests and activities of other related and cooperating agencies through a constant sharing and interchange of ideas and service, the more soundly and economically will it fulfill its purpose (National Organization for Public Health Nursing, 1939, p. 15).

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to

Define collaboration, coalition building, and community organizing.

Apply collaboration, coalition building, and community organizing strategies at appropriate levels of practice.

Explore evidence-based ways that public health nurses practice these strategies to impact public health outcomes.

KEY TERMS

Coalition building

Collaboration

Community organizing

The interventions in the orange section of the Minnesota Department of Health Population-Based Public Health Nursing Practice Intervention Wheel are presented in this chapter. This orange section includes the three interventions of collaboration, coalition building, and community organizing as depicted in the wheel conceptual model (Keller, Strohschein, & Briske, 2008; Minnesota Department of Health, 2001). This chapter devotes a separate section to each of the three interventions. Section one is about collaboration, section two presents coalition building, and section three discusses community organizing. Together, these three interventions are considered types of “collective action” (Keller et al., 2008, p. 193). Each of these three interventions is discussed with examples of how they are applied at the appropriate level of intervention: individual/family, community, and system. Each of the following sections (collaboration, coalition building, and community organizing) describes evidence-based practices used to address the issue examined in depth in this chapter: physical inactivity. The application of these interventions to this important 21st-century public health crisis illustrates aspects of how each intervention strategy works and reinforces key concepts.

Issue: Physical Inactivity Is a Major 21st Century Public Health Concern

Today, leading experts consider physical inactivity to be one of the most critically important public health problems of our times (Blair, 2009; Sallis, 2009). In 2003, physical inactivity was estimated to be responsible for over 200,000 deaths each year in the United States (Pate et al., 2006). Additionally, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002) estimates that worldwide, 2 million deaths per year can be attributed to physical inactivity, making it a global health crisis as well. For the second time in history, the United Nations met to focus on a public health issue: the problem of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). At this Summit, organized by the WHO, the critical need to better address the enormous global burden of these diseases was recognized. NCDs include heart attacks and strokes, cancers, diabetes, and chronic respiratory disease, and account for over 63% of deaths in the world (WHO, 2011). Every year, NCDs kill 9 million people under the age of 60. According to the WHO, “NCD’s are largely preventable by means of effective interventions that tackle shared risk factors, namely: tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and harmful use of alcohol” (WHO, 2011, para. 1). Substantial improvements in health and quality of life are possible by including moderate amounts of physical activity in daily life, according to evidence-based findings from a major report updated in 2008 by the Surgeon General on physical activity and health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [U.S. DHHS], 1996, 2008). The health benefits of physical activity and its importance in promoting good overall health and in reducing the risk of many chronic diseases, such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, depression, and some cancers, and obesity are well known (Blair, 2009; Pollard, 2003). Strong evidence is emerging on the role of physical activity in brain health and the delay of cognitive decline (Blair, 2009).

In spite of this evidence that regular physical activity is necessary for health promotion and disease prevention for all populations, individuals in age groups from children to adolescents to older adults are not engaging in sufficient physical activity to achieve these benefits. According to the WHO (2002), 60% of the world’s population does not get enough physical activity to achieve even the minimal recommendation of at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity per day. For

those who do not follow the minimum recommendations for physical activity, the risk of getting a cardiovascular disease increases by 1.5 times.

those who do not follow the minimum recommendations for physical activity, the risk of getting a cardiovascular disease increases by 1.5 times.

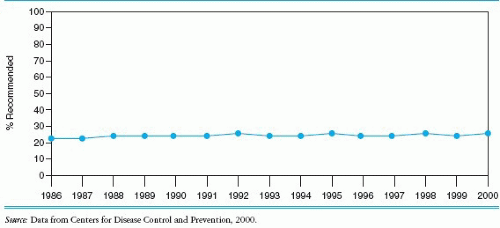

Further, the costs associated with inactivity and obesity accounted for some 9.4% of the national U.S. health expenditure, whereas in Canada physical inactivity accounted for about 6% of total healthcare costs in 1995. Data from 1998 indicate that in the United States, individuals who are physically active save an estimated $500 per year in healthcare costs. It is reported that inactivity alone may have contributed as much as $75 billion to U.S. medical costs in the year 2000 (WHO, 2002). In the United States, there has been no increase in the level of physical activity participation from 1986 through 2000 (Figure 12-1), implying that most of the strategies during this time period have been ineffective in increasing physical activity participation in Americans. Indeed, data for deaths from low (cardiorespiratory) fitness indicate that it kills more Americans than smoking, diabetes, and obesity (“smokadiabesity”) combined (see Figure 12-2) (Khan & Tunaiji, 2011).

Figure 12-2 A comparison of deaths attributable to low fitness (men (m) and women (w)) and the combined effect of smoking (S), diabetes (D) and obesity (O) (men and women). Slide represents the identical data published by Blair (2009). |

Experts suggest that new strategies and innovative approaches are needed to impact physical activity participation and health outcomes (Blair, 2009; Pollard, 2003). As discussed, interventions of collaboration, coalition building, and community organizing can be effective in accomplishing this goal.

Minnesota Department of Health Population-Based Public Health Nursing Practice Intervention Wheel Strategies and Levels of Practice

Collaboration

A working definition of collaboration has been offered as:

{A} mutually beneficial and well-defined relationship entered into by 2 or more organizations (individuals) to achieve common goals. The relationship includes a commitment to: a definition of mutual relationships and goals; a jointly developed structure and shared responsibility; mutual authority and accountability for success; and a sharing of resources and rewards. (Mattessich & Monsey, 1992, p. 7)

Collaboration has been defined in the intervention wheel as an approach that “commits 2 or more persons or organizations to achieving a common goal through the enhancement of the ability of one or more of them to promote and protect health” (Keller et al., 2008, p. 204). We know that public health nursing may be practiced by one public health nurse or by a group of public health nurses working together or collaboratively.

Clearly, collaboration with other healthcare professionals or with those in other organizations working toward mutual goals is often part of the work of the public health nurse to promote the health of any population. In fact, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has called for the integration of interprofessional education into health professions curricula to improve healthcare quality. Six professions, including nursing, collaborated in producing the Interprofessional Education Collaborative report, which states that “policy, curricular, and/or accreditation changes to strengthen teamwork preparation are at various stages of development among the six professions represented in this report” (2011, p. 5). In addition, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing has integrated interprofessional collaboration behavioral expectations into its Essentials for Baccalaureate, Master’s and Doctoral Education for Advanced Practice.

Working in collaboration with others to achieve goals requires that public health professionals and practitioners possess or acquire skills that are applied to develop a shared vision and agree on an effective plan of action (Sullivan, 1998). However, although collaboration is often highly effective in increasing the quality of results and offers the potential of many benefits, including the opportunity for a more comprehensive evaluation and assessment of issues, collaborative projects may not always work (Gray, 1998). An understanding of how successful collaborations are formed is important in considering, or undertaking, a collaborative effort.

In 1992, the Wilder Research Center offered a theoretical understanding of what is needed for collaboration to succeed (Mattessich & Monsey, 1992). An initial review of 133 studies identified 18 relevant and valid studies, and the combined findings from these studies resulted in identification of 19 factors reported to influence whether or not a collaboration formed by government agencies and nonprofit organizations will succeed. These factors were grouped into six key categories: (1) environment, (2) membership,

(3) process/structure, (4) communications, (5) purpose, and (6) resources. The 19 factors are listed in the category to which they belong and are described in Box 12-1.

(3) process/structure, (4) communications, (5) purpose, and (6) resources. The 19 factors are listed in the category to which they belong and are described in Box 12-1.

This information can be useful in guiding the decision to enter into a partnership with potential collaborators by a careful evaluation of whether the important factors for success exist before undertaking an effort. Not every collaboration, however, is the same, and the exact combination of the factors for success may not always be identical. Consideration of these factors can assist those who work in public health in assessing the potential of a collaborative approach and in maximizing the impact of collaborative projects (Mattessich & Monsey, 1992).

Collaborative approaches to the problem of physical inactivity have taken on a new importance as the evidence base on physical activity has grown. New models of health behavior and health promotion, such as the social-ecological model, have been developed and are being applied to areas such as physical activity participation (Elder et al., 2007). These models offer new understanding of the many determinants of physical activity and suggest potential interventions at multiple levels of influence on behavior, with a growing emphasis on environmental and policy influences. These models are used to target behavior change beyond the individual level only. As a result, it is increasingly evident to those working in public health and prevention that the decisions and policies in sectors ranging from agriculture to transportation to education may have a huge impact on physical activity participation and health. Yet these groups have not traditionally understood the connections between them nor have they often sought opportunities to collaboratively engage in health promotion efforts.

Box 12-1 Six Categories of Factors That Influence the Success of Collaboration

Environment

A history of collaboration exists in the community.

The collaborative group is seen as a community leader in the area in which it is focused. There is a favorable political/social climate.

Membership

There is mutual respect, understanding, and trust.

Cross-section of members in the group is appropriate.

Collaboration is viewed as being in the self-interest of members.

There is the ability to compromise.

Process/structure

Members share a stake in both the process and groups.

There are multiple layers of decision making.

There is flexibility and openness.

Clear roles and policy guidelines are developed.

There is adaptability in the face of changing conditions.

Communications

There is open and frequent communication.

Formal and informal communication links exist.

Purpose

There is a concrete and unique purpose.

There are clear, realistic, and attainable goals.

There is a shared vision, with an agreed-on mission, objectives, and strategy.

Resources

Funding is sufficient to support operations.

The leader, or convener, of the collaborative group is skilled interpersonally and is fair and respected by partners.

Source: Adapted from Mattessich and Monsey, 1992.

Important environmental and policy approaches may be implemented by applying collaboration, coalition building, and community organizing interventions. These approaches can effect physical activity participation at the population-based level, complementing the individual-level focus of changing one person’s behavior at a time (Heath et al., 2006).

Projects that involve the collaboration of those from multiple sectors are promising approaches to impact physical activity at the population level (Pollard, 2003). The impact of the built environment—the man-made physical structures and infrastructure of communities (Prevention Institute, 2009)—on health and the potential to alter aspects of the built environment to promote health are now being recognized by public health professionals (Pollard, 2003). Offering opportunities for walking and cycling as a regular part of daily life, for example, are important to increasing physical activity and to improving health among a largely sedentary population in the United States. To promote healthier communities, multiple approaches directed at all levels of the government—local, state, and federal—are needed. The creation of communities and transportation systems that promote physical activity require the support of public health professionals working collaboratively with other disciplines such as architects, builders, public officials, bike and pedestrian advocates, and others on common concerns (Pollard, 2003).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree