Hitting the Pavement: Intervention of Case Finding: Outreach, Screening, Surveillance, and Disease and Health Event Investigation

Margaret Macali

Marie Truglio-Londrigan

|

While visiting in a home recently to look up a case of a one-year-old child that was blind (and will be so permanently, but could have been given its sight if the proper medical care had been given it when born) I also found a seven-year-old boy whose leg was drawn up in a V-shape with the knee quite rigid. I found the child had fallen, broken the leg at the knee, and, never having had a physician, the bones knit in the position described. I referred the case to a specialist on children who performed an operation and, after lying in a hospital six months, the boy left using both his legs… . The great work of the visiting nurse, socially, lies in this field, not only relieving petty ailments and dealing with the common diseases, but searching out the cases that other wise go unattended (Steel, 1910, p. 341).

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to

Describe the red wedge of the Minnesota Department of Health Population-Based Public Health Nursing Practice Intervention Wheel Strategies, which includes case finding, outreach, screening, surveillance, and disease and health investigation.

Verbalize culturally appropriate and congruent ways to initiate these intervention strategies.

Explore the various ways that public health nurses apply and perform the strategies of case finding, outreach, screening, surveillance, and disease and health investigation.

KEY TERMS

Case finding

Disease and health event investigation

Outreach

Screening

Surveillance

Directly Observed Therapy

Index case

The strength of the Minnesota Department of Health Population-Based Public Health Nursing Practice Intervention Wheel Strategies (Keller, Strohschein, & Briske, 2008; Minnesota Department of Health, 2001) is in the identification of specific intervention strategies and the level of practice (systems, community, and individual/family) that are applied by public health nurses who are charged with protecting the public’s health. “Protecting the public” are words that have historically inspired a few so that the many may live healthy lives. The purpose of this chapter is to present to the reader one section of the intervention wheel (red section), which includes case finding, outreach, screening, surveillance, and disease and health event investigation. Case finding, as an intervention strategy, takes place at the individual/ family level of practice.

This chapter is divided into several sections. The first is the description of these key intervention strategies. The second is a demonstration of how these intervention strategies are applied within the context of several public health issues. The third is the presentation of a case study, so that readers may understand the process of these interventions. The final section is a look at the case study and the application of the intervention strategies to the various levels of practice, including individual/family, community, and system.

Minnesota Department of Health Population-Based Public Health Nursing Practice Intervention Wheel Strategies

Case Finding

Case finding is exactly what the words imply: to find new cases for early identification of a client with a particular disease or to find cases where particular contact person(s) may be at risk for developing a certain disease. Liebman, Lamberti, and Altice (2002) noted that case finding is important from several points of view. First, by identifying individuals with a particular disease, treatment may be provided in a timely way, thus resulting in reduced morbidity. Second, the identification of individual(s) prevents further transmission of the disease. Finally, in addition to the early identification of individual(s) with a disease

through case finding, the process of case finding is also significant in the identification of highrisk individual(s) and “serves as an important opportunity for health education and teaching to promote primary prevention of disease, even among those found not to be infected” (p. 345).

through case finding, the process of case finding is also significant in the identification of highrisk individual(s) and “serves as an important opportunity for health education and teaching to promote primary prevention of disease, even among those found not to be infected” (p. 345).

Case finding is essential to identify individuals at risk for disease. Case finding is also important for early diagnosis of those with infectious and noninfectious disease(s), including foodborne and waterborne illnesses. In recent years the process of case finding has also been instrumental in the identification of individuals experiencing still other noninfectious disease(s), including chronic illness; mental health issues such as anxiety and depression; and social, spiritual, emotional, or environmental issues including abuse, violence, and addictions. Skjerve et al. (2007), for example, studied the use of a cognitive case-finding instrument known as the sevenminute screen in a population of older adults for the identification of dementia. Jack, Jamuson, Wathen, and MacMillan (2008) explored public health nurse perceptions of screening for intimate partner violence (IPV) and noted that “screening using a standard set of questions is difficult to implement … the standard practice is to assess for mothers’ exposure to IPV during in-depth assessment of the family; the nature of in-depth assessment having a case-finding rather than screening approach” (p. 150). Puddifoot et al. (2007) looked at anxiety as a treatable condition that frequently goes untreated because it is not diagnosed; the key question here is how to find the unidentified case. These researchers studied whether two simple written questions would aid in the identification of anxiety in a particular person, thus facilitating case finding and ultimately treatment. Similarly, Damush et al. (2008) noted how post-stroke depression is often undiagnosed and ultimately untreated, resulting in an increase in morbidity and mortality. The purpose of this study was to determine if detecting patients with poststroke depression in administrative databases using a case-finding algorithm among veteran stroke survivors would be possible. The essence of case finding in these particular situations is that this process identifies individuals in need and connects those individuals to resources such as treatments, support groups, agencies, counseling, and other support services. This echoes the words of Keller and colleagues (2008), who stated, “case finding locates individuals and families with identified risk and connects them with resources” (p. 199). There are various strategies that the public health nurse may use that facilitate and sustain this case-finding process. One needs only to ask how to find these cases. The answer is outreach, screening, surveillance, and disease and health event investigation.

Outreach

The public health nurse may use various strategies to engage in case finding. One of these strategies is outreach. The word “outreach” creates a vision for us in which the public health nurse or other public health practitioner actually reaches out into the community and connects with and helps those in need. Keller et al. (2008) noted that “outreach locates populations of interest or populations at risk and provides information about the nature of the concern, what can be done about it, and how services can be obtained” (p. 199). Rajabiun et al. (2007) described a qualitative study in which they investigated the process of engagement in HIV medical care. Analysis of the data demonstrated that the participants frequently cycled in and out of care based on a number of influences. The researchers identified that those individuals who had cycled out of care must be found so that care could be reestablished. Outreach, however, was identified as an intervention that played a significant role

in connecting participants back to the needed care, thus enhancing care of the individual and in the process protecting the public.

in connecting participants back to the needed care, thus enhancing care of the individual and in the process protecting the public.

The process of outreach is not a simple one. The public health nurse must take into account the specific population of interest, the demographics of that population, the particular problem that needs to be addressed, where they live, the resources available to them, that particular population’s values and beliefs, how they live in the world, and whether or not they want to be found. Although the entire process is rather complicated, the actual enactment requires four important steps.

The first is how the outreach will be carried out so that the public health nurse can gain access to the population and find those in need, hence case finding. Is it via mobile van, motorcycle, walking in the community, telephone calls, knocking on doors, or any other method of connecting with the population of interest? In a school-based community health course, Truglio-Londrigan et al. (2000) worked with community health nursing students in a senior housing project. To gain access to the population of older adults to identify their individual needs, the students knocked on the 99 doors of the building. The students in this course believed that the doors in the apartment buildings were there for protection by keeping people out, but they were actually a barrier to care and services. Their answer to this was to knock on every single door and meet every single person living in the apartment complex. Nandi et al. (2008) assessed access to and use of health services in Mexican-born, undocumented individuals in New York City. To gain access to this population, recruitment took place in communities with large populations of Mexican immigrants. Areas were selected in two phases. In the first, the U.S. Census data were used to identify neighborhoods with the highest numbers of the targeted population. The second step in the process was a walk-through of the key identified neighborhoods to conduct interviews. Finally, Liebman et al. (2002) noted that a mobile van was an innovative approach to case finding. The authors identified that the use of the van was a way for professionals to move out into communities and gain access to hard-to-reach populations who may not come into traditional health clinics.

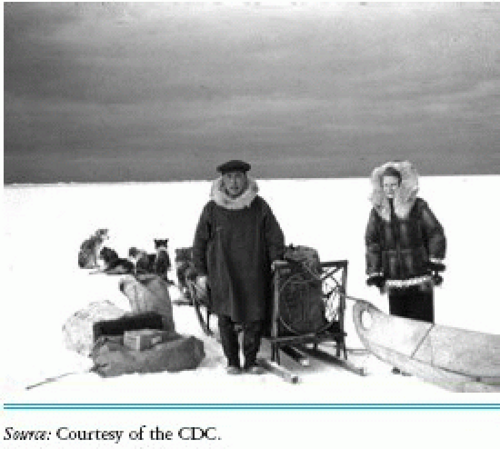

The photo on this page provides an example of how one particular public health nurse reached out and gained access to populations of interest. As you examine this photo, look at the nurse and imagine that it is you in the photo. What are you thinking? Who are you visiting? Where do they live? What do you suppose you will find when you reach the end of your destination? What type of services do you suppose you will provide?

A second important consideration is the person who will be doing the outreach. Will the person be a lay worker who lives in the community and is a member of the population of

interest? Mock et al. (2007) wanted to promote cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese American women. To determine the effectiveness of this approach, a study was designed to look at lay workers who did the outreach plus media-based education (combined intervention) and media-based education only. Vietnamese woman acted in the role of lay outreach coordinators and lay health workers. Ultimately, the combined intervention motivated more Vietnamese American women to obtain their Pap tests than did media education alone, thus identifying that the person doing the outreach may have a significant impact on whether or not individuals in need will be found and ultimately connected with the needed care and/or resources. Findley et al. (2008) presented a coalition-led childhood immunization program that included an outreach component in which trained peer educators were used. Other elements of this initiative included bilingual and communityappropriate materials as well as reminders to parents. Results demonstrated that students enrolled in this program were more likely to receive timely immunizations than children not enrolled in the program, again demonstrating the importance of finding cases and connecting those cases to needed care and resources. Toole et al. (2007) wanted to conduct a survey of homeless individuals to determine their needs. The difficult part of this type of research is how to find these homeless individuals, so the researchers enlisted formerly homeless, trained, research assistants to aid in the process.

interest? Mock et al. (2007) wanted to promote cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese American women. To determine the effectiveness of this approach, a study was designed to look at lay workers who did the outreach plus media-based education (combined intervention) and media-based education only. Vietnamese woman acted in the role of lay outreach coordinators and lay health workers. Ultimately, the combined intervention motivated more Vietnamese American women to obtain their Pap tests than did media education alone, thus identifying that the person doing the outreach may have a significant impact on whether or not individuals in need will be found and ultimately connected with the needed care and/or resources. Findley et al. (2008) presented a coalition-led childhood immunization program that included an outreach component in which trained peer educators were used. Other elements of this initiative included bilingual and communityappropriate materials as well as reminders to parents. Results demonstrated that students enrolled in this program were more likely to receive timely immunizations than children not enrolled in the program, again demonstrating the importance of finding cases and connecting those cases to needed care and resources. Toole et al. (2007) wanted to conduct a survey of homeless individuals to determine their needs. The difficult part of this type of research is how to find these homeless individuals, so the researchers enlisted formerly homeless, trained, research assistants to aid in the process.

A third consideration is how the message will be delivered to the population once the connection is established. Is it via the newspaper, flyers, booklets, television ads, songs, radio announcements, Internet advertisement, text messaging, or some other technological advancement not yet discovered? The importance of knowing the target population is critical. The public health nurse may have a plan for an outreach process that is well developed and the population is identified and accessible, but if the message is developed in a way that is not congruent with the population, the message will miss its mark. For example, several years ago community health nursing students identified a need in conjunction with a county department of health and the office on aging in a local county. That need was to deliver nutritional education to the population of older adults living in a particular community. The community students went to the nutrition center and spoke with the older adults, and indeed these older adults concurred that programs on nutrition would be very beneficial for those who used the nutrition center. The community students spent a great deal of time in the development of the program. On the day in which the program was delivered, this author was conducting an observation and noted that students arrived in costumes of the “Fruit of the Loom Guys” traditionally seen on the television undergarment commercials. The costumes were great and the older adults loved them. When the students progressed up to the stage to deliver the message, it was very clear that while their presentation was intriguing to the older adults, the minute they began to deliver their message they lost the attention of their population. The community students had developed a rap song about the food groups. In the audience the older adults began to look confused, many asking, “What are they saying?” The message was lost because the connection was lost. The message that the students developed was not congruent with the population they were targeting. This is similar to concepts pertaining to health teaching and educational programming, covered later in this text.

Finally, the fourth component for consideration is where the final point of contact or service in the outreach process is being rendered. The example given above concerning

the presentation of a nutritional program for older adults in a community nutrition site is an example of the final point of contact for the program delivery. Toole et al. (2007) discussed the dilemma of the homeless and raised the question of where they may go when they first become homeless. The lack of access to services creates a situation where the homeless person will increasingly be more likely to experience poor health. The investigators of this research had to think about how they could access this population to hear the voices of these vulnerable people. The researchers knew if they were going to be successful in gaining access to this population and to find individuals, they must go to where they were. These areas included “(i) unsheltered enclaves (including abandoned buildings, cars and outdoors) and congregate eating facilities without sleeping quarters; (ii) emergency shelters; and (iii) transitional housing or single room occupancy (SRO) dwellings” (p. 448). It is not unheard of for public health nurses to ride city buses day and night into neighborhoods where they know their clients travel, in an attempt to find them and give the care they may need. Table 9-1 provides examples of points-of-contact for targeted populations.

the presentation of a nutritional program for older adults in a community nutrition site is an example of the final point of contact for the program delivery. Toole et al. (2007) discussed the dilemma of the homeless and raised the question of where they may go when they first become homeless. The lack of access to services creates a situation where the homeless person will increasingly be more likely to experience poor health. The investigators of this research had to think about how they could access this population to hear the voices of these vulnerable people. The researchers knew if they were going to be successful in gaining access to this population and to find individuals, they must go to where they were. These areas included “(i) unsheltered enclaves (including abandoned buildings, cars and outdoors) and congregate eating facilities without sleeping quarters; (ii) emergency shelters; and (iii) transitional housing or single room occupancy (SRO) dwellings” (p. 448). It is not unheard of for public health nurses to ride city buses day and night into neighborhoods where they know their clients travel, in an attempt to find them and give the care they may need. Table 9-1 provides examples of points-of-contact for targeted populations.

Screening

Another strategy that public health nurses may decide to use in their process of case finding is screening. Keller et al. (2008) stated that “screening identifies individuals with unrecognized health risk factors or asymptomatic disease conditions in populations” (p. 199). Leavell and Clark (1965) addressed the concept of screening as an intervention strategy that is beneficial in its ability to engage in case finding for individual(s); it can provide early identification of a disease, thus facilitating prompt treatment. This early identification is considered in the secondary level of prevention during the early pathogenesis period when the person(s) is asymptomatic. The benefits of screening and early identification of disease are numerous:

Early detection and diagnosis, leading to early treatment

Early detection breaking the chain of transmission and development of new cases

Early detection leading to a decrease in morbidity and mortality

Early detection leading to lower costs pertaining to treatments

Early detection protecting the community and/or the targeted population

Table 9-1 Examples of Outreach and Gaining Access to Targeted Populations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

This improvement in health and well-being is documented in the literature. Hartge and Berg (2007) noted that “women can improve their prospects for long-term health by being screened for several cancers with tests proved to decrease morbidity and mortality from colorectal, breast, and cervical cancer” (p. 66). Liebman and coworkers (2002) identified that case finding via screening not only is significant because it breaks the chain of further transmission, but it also may identify individuals who present with high-risk behavior. This knowledge therefore provides opportunities for education that focuses on primary prevention and health promotion. This identification of individuals at risk for a disease through screening presents with the same benefits listed above and also includes the following:

Early detection of high-risk behaviors and modifiable risk factors, leading to prevention of disease

Early detection leading to empowerment of the person or the population being targeted

Early detection leading to improvement in lifestyle and quality of life

The application of screening to identify individuals at risk for developing disease takes us closer to health promotion and disease prevention. Wimbush and Peters (2000) described the implementation of a cardiovascular-specific genogram that may be used to identify persons at risk for cerebrovascular disease within families. These authors further described the complex array of risk factors associated with cerebrovascular disease and noted the differences between modifiable risk factors, such as lack of exercise, high fat and high sodium diets, high blood cholesterol, obesity, smoking, high blood pressure, and stress, as compared with nonmodifiable risk factors, such as age, gender, and genetic predisposition. The application of the genogram, a tool used to illustrate family health and relationship patterns over generations, facilitates the public health nurse’s understanding of risks present in a family and which of those risks are modifiable. The use of the genogram, in this way, demonstrated promise as a tool to obtain data to inform the public health nurse as to individuals at risk for cerebrovascular disease. Fedder, Desai, and Maciunskaite (2006) similarly presented a strategy that was based on an infectious disease management model that would improve early detection. The authors proposed that practitioners consider “a chronic disease event—e.g., a heart attack, breast cancer diagnosis, or diabetes mellitus diagnosis—as the index case and then screen the siblings and progeny (their brothers, sisters, and children), who are predictably at higher risk” (p. 331). Again, the overall goal is to increase awareness and target risky behavior in others, facilitating prevention and health promotion.

Screening takes place in individual and mass screening models. Screening for the individual involves working with one person and performing a screening test such as taking a blood pressure reading. Conversely, a mass screening may be a situation where a particular group is targeted for a particular screening program pertaining to one or even multiple diseases. The reason the particular group may be targeted has to do with data derived either from an assessment or surveillance data. These data are a source of information for the public health nurse and inform the nurses’ decision making.

The data may indicate that the group in question is at greater risk for the development of a particular disease, such as diabetes. In this case, the public health nurse may engage in an initiative to develop and implement a mass screening to identify new cases of this disease.

The data may indicate that the group in question is at greater risk for the development of a particular disease, such as diabetes. In this case, the public health nurse may engage in an initiative to develop and implement a mass screening to identify new cases of this disease.

The benefits of screening are well documented; however, there are limitations as well. One such limitation is what happens to the individual once he or she is informed that the screening test is positive. For example, in the mass screening above, what happens to an individual who is told that his or her blood sugar level is elevated? What type of followup is provided? What good is this type of mass screening if the public health nurse finds a case but there is no mechanism to ensure that the individual has access to care for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up? The University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey’s Mobile Health Care Project addressed this issue. They established a collaborative, joint partnership initiative with the Children’s Health Fund where a nurse-faculty-managed mobile healthcare unit provided care to the underserved population of Newark, New Jersey. One of the goals of this initiative was to provide health promotion services in the form of screenings. Individuals with positive findings were referred to the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey hospitals and affiliates for treatment and additional referrals (McNeal, 2008), thus making sure people had access to the care they needed.

Although the benefits of screening are well known, the public health nurse and other public health practitioners must engage in continual dialogue in terms of deciding if a disease is in fact screenable. Escriba-Aguir, Ruiz-Perez, and Saurel-Cubizolles (2007) discussed this issue and identified that if a screening program is to be undertaken, several assumptions must be met: “(a) existence of a test with good sensibility and specificity, (b) high incidence of the problem, (c) existence of appropriate intervention and support measures…, and (d) the diagnostic tool should be acceptable for the population to whom it is aimed and for professionals who apply it” (p. 133).

The issue of sensibility and specificity is an important one. The UK National Screening Committee (2008) offers advice and recommendations about screening based on evidence: “In any screening program, there is an irreducible minimum of false positive results (wrongly reported as having the condition) and false negative results (wrongly reported as not having the condition)” (n.p.). This concern is further defined by others when they speak to the concepts of sensitivity and specificity to address this issue. “Sensitivity quantifies how accurately the test identifies those with the condition or trait … . Specificity indicates how accurately the test identifies those without the condition or trait” (McKeown & Hilfinger Messias, 2008, p. 261).

It is evident that there are also ethical and economic considerations to be considered in these cases. For example, the public health nurse and other public health practitioners need to consider the following questions with regard to these possibilities. How ethical is it to conduct screening tests that may inform people they have a disease when they do not? Will these individuals engage in unnecessary testing? Who will pay for the cost of this unnecessary testing? Are there any adverse effects of this unnecessary testing? What is the emotional trauma that the individual will experience and is this important to consider? How ethical is it to conduct screening tests that may inform people that they do not have a disease when in fact they do? What will happen to these individuals? How much later will they be diagnosed and will the diagnosis be too late for any effective treatment modality? What is the emotional trauma that

this individual will experience? Will the screening produce positive health outcomes, i.e., a healthier population? The Public Health Action Support Team (2010) posted an online tutorial entitled Health Knowledge: Screening, which addresses many of these questions and speaks about screening not as a singular test but as a process and a program. This tutorial discusses the importance of commissioning high-quality screening “programs” that are efficient, coordinated, and of good value. Taking the time to access this video will provide you with a comprehensive understanding of screening that also considers cultural nuances.

this individual will experience? Will the screening produce positive health outcomes, i.e., a healthier population? The Public Health Action Support Team (2010) posted an online tutorial entitled Health Knowledge: Screening, which addresses many of these questions and speaks about screening not as a singular test but as a process and a program. This tutorial discusses the importance of commissioning high-quality screening “programs” that are efficient, coordinated, and of good value. Taking the time to access this video will provide you with a comprehensive understanding of screening that also considers cultural nuances.

Public health nurses and other public health practitioners may also refer to the work of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for practice decisions with regard to the above. The USPSTF, sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, is a panel of experts in prevention and primary care. The USPSTF conducts rigorous systematic assessments of evidence for the effectiveness of preventive services such as screening, counseling, and preventive medications. The mission of the USPSTF is to “evaluate the benefits of individual services based on age, gender, and risk factor for disease; make recommendations about which preventive services should be incorporated routinely into primary medical care and for which populations and identify a research agenda for clinical preventive care” (USPSTF, 2010, n.p). Based on these evaluations the USPSTF assigns one of five letter grades to each of its recommendations (A, B, C, D, or I). Box 9-1 provides an explanation of this grading system and its application for practice.

As of October 2008 there were new screening guidelines for colorectal cancer. The USPSTF recommends screening for colorectal cancer using fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy in adults beginning at age 50 years and continuing until age 75 years. This guideline was given a grade A recommendation. As seen in Box 9-1, the grade A means that the USPSTF strongly recommends that clinicians routinely provide the service to eligible patients, thus providing guidance to healthcare providers in the clinical practice setting. The guidelines for this particular situation are listed as grade A recommendations for the age group 50 to 75 years, but not for those ages 76 to 85 years. The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for colorectal cancer in adults ages 76 to 85 years; however, there may be considerations that support colorectal cancer screening in an individual patient. In this situation the grade of C recommendation means the USPSTF makes no recommendation for or against routine provision of the service. Finally, the USPSTF recommends against screening for colorectal cancer in adults older than age 85 years. This recommendation was given a grade of D meaning that the evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms (USPSTF, 2008). Again, these recommendations provide guidance to the healthcare provider in the clinical practice setting. These guidelines also state that the USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of computed tomographic colonography and fecal DNA testing as screening modalities for colorectal cancer. In this situation the grade of I is recommended.

Screening is an important strategy for case finding; however, as identified above there are challenges that must be addressed. Wald (2007) addressed these challenges in an editorial, noting that the type of quantitative information needed on the screening performance of a test is usually not even known. “The culture needs to change, so that screening is subject to professional scientific assessment before it is promoted to the public” (Wald, 2007, p. 1).

Box 9-1 USPSTF Grade Definitions

The USPSTF grades its recommendations according to one of five classifications (A, B, C, D, I), reflecting the strength of evidence and magnitude of net benefit (benefits minus harms).

A: The USPSTF strongly recommends that clinicians provide [the service] to eligible patients. The USPSTF found good evidence that [the service] improves important health outcomes and concludes that benefits substantially outweigh harms.

B: The USPSTF recommends that clinicians provide [this service] to eligible patients. The USPSTF found at least fair evidence that [the service] improves important health outcomes and concludes that benefits outweigh harms.

C: The USPSTF makes no recommendation for or against routine provision of [the service]. The USPSTF found at least fair evidence that [the service] can improve health outcomes but concludes that the balance of benefits and harms is too close to justify a general recommendation.

D: The USPSTF recommends against routinely providing [the service] to asymptomatic patients. The USP-STF found at least fair evidence that [the service] is ineffective or that harms outweigh benefits.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access