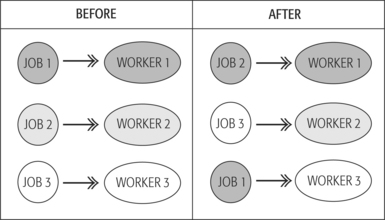

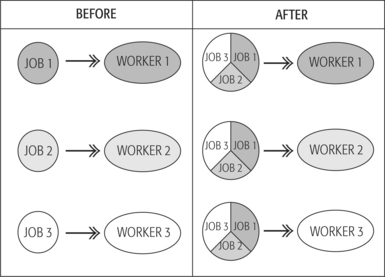

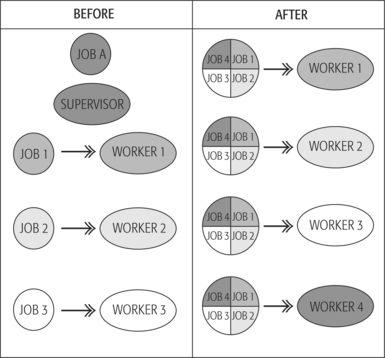

CHAPTER 11 Work design in health care After studying this chapter, the reader should be able to: The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of the way we design work in health care. In an era of increasing industrial restructuring, job design and redesign are important in the role of the health service manager. The jobs of individual workers must be changed to improve quality of care, increase productivity, and reduce costs in response to external pressures, as well as increasing staff satisfaction, motivation and retention. A further important early publication was that by the engineer Charles Babbage in 1835, titled On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, written during the time of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of large factories in the United Kingdom and the United States. This focus on organising work into increasingly divided tasks, which were standardised to allow for easy replication and minimal error, was continued by Frederick Winslow Taylor (1911), Frank and Lillian Gilbreth (1911) and others. Taylor’s (1911) publication, Scientific Management, was the first book to describe efficient work design. Taylor was an engineer with a Pennsylvanian steel company and he believed worker output could be increased through work redesign. His influence on management practices and worker productivity has been enormous. Much like Adam Smith in the eighteenth century, Taylor (1911) believed in the division of labour such that each job should be examined scientifically, broken down into small parts and standardised in order that workers should perform at maximum efficiency. Workers were also rewarded financially for increased productivity. However, despite the financial incentives associated with Taylor’s approach, there was a high human cost in some industries. These costs included high levels of staff turnover and absenteeism as a result of worker boredom with the repetitious nature of many jobs and general worker dissatisfaction and ‘alienation’ (Braverman 1974). This has led many to claim that Taylor’s approach to management is inhumane. Nevertheless, the popularity of his work with managers gave rise to later movements such as work simplification and human engineering. Importantly, Taylor sought to create a paradigm shift in management and worker thinking in the interests of improved production efficiency. Today, managers use many of his ideas when designing jobs. Among Taylor’s ideas still in vogue (Dunphy 1981) are the: What was missing from classical management theories was an understanding of human behaviour and motivation. The work of the human relations theorists, such as Mayo (1933), Maslow (1943) and Herzberg et al (1959), brought a new job design emphasis to management thinking. These theorists investigated the psychosocial meaning of work and the needs of workers to be ‘enriched’ by work. They recognised that powerful social norms operated within work groups and that these affected worker productivity. These social norms were influenced by formal and informal leaders and modes of communication and by worker participation in decisionmaking. Unlike the classical management theorists, who considered that workers were primarily motivated by ‘extrinsic’ factors, such as money, the human relations theorists emphasised the importance of ‘intrinsic’ motivators such as recognition, selfesteem and self-actualisation (Maslow 1943). Despite these differences, the ultimate intent of both groups of theorists was to increase worker productivity efficiency (viz to achieve more with less). In other words, meeting the higher level social needs of workers was not an end in itself. Herzberg et al (1959, p ix) maintained that both management and workers stood to gain from studies of worker attitudes to their jobs. Among the claimed benefits for management were increased worker productivity, decreased staff turnover and absenteeism, and smoother working relations. Potential benefits for individual workers were a happier work environment, improved job satisfaction and enhanced self-esteem. The origin of the term ‘job design’ is generally attributed to two United States researchers, Davis and Canter (1955), who wrote (p 3): Davis (1979, p 30) originally defined job design as: ‘the organization (or structuring) of a job to satisfy the technical-organizational requirements of the work to be accomplished and the human requirements of the person performing the work …’. The first ‘field’ experiment on job design was conducted in an assembly department in a unionised pharmaceutical plant in the United States. The work was redesigned from a linear assembly line operation with serial work stations to a group-based assembly operation, and finally to an individual product-based assembly operation, in which groups of workers assembled a total product (Davis 1979). The results of this experiment showed an improvement in the quality of the product but no gain in productivity. Importantly, it also showed a positive change in worker attitudes, with workers developing: In the United Kingdom, a similar approach to job redesign was being used. The name given to the UK model was the ‘socio-technical systems’ approach. Trist and Bamforth (1951) of the Tavistock Institute undertook some of the earliest sociotechnical systems studies. Their research involved workers in the Durham coalmine. With this approach to job redesign, the focus of analysis became the work group rather than the individual. Second, it combined concepts from group dynamics and systems theory to inform the analysis and the redesign of jobs. Three systems were defined and analysed: technological, social and economic. Finally, it involved restructuring work around groups that, when functioning well, were cohesive, semiautonomous and self-regulating (Fulop & Mortimer 1992). state of the art practices in such disciplines as organisation development, management engineering, labor [sic] relations, quality control, and human resources development. Although implementation of the QWL concept varies from one organization to another, all QWL programs attempt to modify existing organization structures, systems, and management processes by involving employees in decision-making processes that lead to enhanced organizational performance and greater employee satisfaction. Quality working life research includes studies of job satisfaction, job rotation, job enlargement, job enrichment, flexible working hours, job sharing, semi-autonomous work groups, and the confusing and contentious concept of industrial democracy (Davis & Cherns 1975; Ramsay 1980). These issues are discussed later in this chapter. In 1972, Senator Edward Kennedy proposed a Bill to the US Senate to deal with the problem of alienation among workers. The Bill, titled ‘Worker Alienation Research and Technical Assistance Bill’, was seeking $20 million to research the physical and mental ill-health of American workers whose alienation within the workforce was expressed in poor quality work, high turnover, absenteeism, sabotage and ‘monetary loss to the economy’ (Ramsay 1985, p 52). Ted Mills (1985), President of the American Center for Quality of Work Life, founded in 1973, saw QWL as part of a societal transformation toward a ‘participative revolution’ (Burbank & Grant 1985, p vii). The application of QWL (including job redesign) was not seen in health care organisations until the early 1980s (Burbank & Grant 1985). Job rotation may be described as an organised method to move workers from one job to another. Workers usually remain at the same level in the organisation’s hierarchy with no fundamental changes to the different jobs through which they rotate (see Figure 11.1). There are two major advantages of job rotation. First, there is increased flexibility within the workforce as workers become familiar with a number of different jobs within the organisation and so can be dispatched easily to another area in times of staff shortage. Second, new workers can be introduced systematically to a number of different jobs undertaken within the workplace as they rotate through jobs. The disadvantage of job rotation is found when workers are unable to focus on one job in order to develop more specialised knowledge (see Case Study 11.1). FIGURE 11.1 Job rotation Source: Adapted from Cherry N, Smyth A, Boucher C 1993 Job design. In: Collins R (ed.) Effective management. CCH, Auckland CASE STUDY 11.1 JOB ROTATION Within the ABC Maternity Hospital a policy of job rotation is in place whereby registered nurses are required to rotate through different areas of the hospital every six months (viz the antenatal wards, postnatal wards, neonatal intensive care and the birthing suite). This policy was established to ensure all staff remain current in all areas of midwifery and thus provide management with the flexibility to relocate staff to various areas in times of staffing shortages (e.g. sick leave, long-service leave, holidays). However, many registered nurses continue to express a desire to remain within the same work location for longer periods of time in order to develop specialist knowledge and skills in the area. They express greater levels of job satisfaction and commitment to a permanent location and reduced levels of stress and anxiety. Job enlargement may be undertaken in two ways: As indicated in Figure 11.2, horizontal job enlargement is an organised method that allows the worker to perform a greater variety of tasks of similar degree of difficulty and at a similar level in the organisation’s administrative structure (or hierarchy). Herzberg (1966) believed that this approach to the enlargement of jobs could result in simply enlarging the number of meaningless jobs performed by individual workers. Even though the workers may be undertaking a greater range of activities within their new job, which could result in greater productivity gains for the organisation, the workers may not be interested in the work. With this approach, the initial gains in levels of worker satisfaction and productivity are usually short-lived (say a few weeks) (Cherry et al 1993). See Case Study 11.2. FIGURE 11.2 Horizontal job enlargement Source: Adapted from Cherry N, Smyth A, Boucher C 1993 Job design. In: Collins R (ed.) Effective management. CCH, Auckland CASE STUDY 11.2 HORIZONTAL JOB ENLARGEMENT In efforts to improve the job satisfaction of registered nurses at the ABC Maternity Hospital, management recently redesigned the job activities of registered nurses. They have moved away from the previous job rotation system, where nurses were required to relocate from one area to another every six months. The new system requires nurses working in postnatal wards to work in the antenatal clinic two mornings per week and nurses working in the antenatal clinic to work in the postnatal ward two mornings per week. Initially, the nurses in both areas agreed to this as a compromise to management so they would not have to rotate to another area every six months. However, after only one week of the new system, nurses from both the antenatal clinic and postnatal clinic sent delegations to the Director of Nursing to express their unhappiness about the new system. The major reason given for dissatisfaction was due to the inability to leave a particular area at a predetermined time because of activities being undertaken; for example, a patient returning from the birthing suite. However, after further discussion, many of the nurses expressed boredom with the type of work being undertaken in the other area. Job enrichment (also known as vertical job enlargement) is an organised method that allows workers to take over some of the tasks previously undertaken by their supervisor (or the person above them in the organisational hierarchy). As Figure 11.3 demonstrates, job enrichment increases the range of tasks undertaken by the worker, and additional responsibility is included in the work performed. Job enrichment can achieve productivity gains because workers have new opportunities for learning tasks previously undertaken by their supervisor. However, such gains may soon evaporate if organisations fail to provide workers with suitable training in order to undertake the additional activities. Also, if workers are simply given additional tasks, which they believe to be boring, then again their motivation and the anticipated productivity gains will be reduced (see Case Study 11.3). Figure 11.3 Job enrichment Source: Adapted from Cherry N, Smyth A, Boucher C 1993 Job design. In: Collins R (ed) Effective management. CCH, Auckland CASE STUDY 11.3 JOB ENRICHMENT (VERTICAL JOB ENLARGEMENT) In light of recent feedback from the staff and a visit from the local nurses’ union representative, the ABC Maternity Hospital decided to undertake a second review of the design of job activities. Survey instruments were used to collect data from all the staff in the hospital on work environment (autonomy, recognition, responsibility and participation in decision-making), staff satisfaction, quality of patient care, and recruitment and retention. Following the analysis of the survey data, the Director of Nursing invited all the clinical nurse consultants (CNCs) and acting directors of nursing (ADONs) in the hospital to attend a two-day (overnight stay) strategic planning retreat held at a beachside resort. Representatives from the various unions and professional associations were invited to present issues papers, as were selected CNCs and ADONs. The results of the surveys were also presented to the group. Break-out workshops were held where brainstorming sessions and whiteboards were filled with a range of possible strategies for redesigning the job activities in order to improve the motivation and satisfaction levels of staff, and also bring about productivity gains for the organisation overall. At one, three and six monthly intervals after the implementation of the new job enrichment system, survey instruments were once again used to collect data from all the staff in the hospital on work environment, staff satisfaction, quality of patient care, and recruitment and retention. A report prepared to compare the data collected before and after the implementation of the new system of job design demonstrated significant levels of improvement in the work environment (autonomy, recognition, responsibility and participation in decision-making), staff satisfaction and quality of patient care. Recruitment costs had reduced significantly for the six months and the levels of intention of the nurses to remain in employment at the hospital had increased. In a memorable episode of the British television series Yes Minister, the producers portray a hospital that is judged to be the most efficiently run hospital of all because its costs are very low and the staff very happy. However, this hospital has no patients, all its beds are empty and its beautiful operating theatres idle. The reality for health care managers is that the raison d’être of most health care organisations is the care of patients. This is essentially a human activity that requires complex human interaction, much more so than in manufacturing industries. Characteristically, health care organisations rely on a large variety of people (paid and unpaid, professional and non-professional) to do the work that needs to be done. At a basic level, the dichotomy between professional and non-professional can be transformed into categories of staff who do things ‘with, to or for patients’ (that is, they have direct patient care responsibility) and those who are not directly involved in the care of patients. Job design in health care therefore has an impact on non-professional staff, and on professional staff and patients. This important aspect of job design is discussed later in this chapter.

Analyse job design and employee motivation in relation to how different types of work designs affect employees.

Analyse job design and employee motivation in relation to how different types of work designs affect employees.

INTRODUCTION

THEORIES AND CONCEPTS UNDERPINNING CURRENT APPROACHES TO JOB DESIGN

Classical management theories

utilisation of output standards on an individual worker basis for each type of job so that the effectiveness of completed work can be assessed;

utilisation of output standards on an individual worker basis for each type of job so that the effectiveness of completed work can be assessed;

provision of adequate payment to workers for achieving targeted output standards (i.e. using the ‘payment by results’ system);

provision of adequate payment to workers for achieving targeted output standards (i.e. using the ‘payment by results’ system);

clear demarcation of skilled and unskilled tasks to avoid paying unskilled workers the same rates as skilled workers; and

clear demarcation of skilled and unskilled tasks to avoid paying unskilled workers the same rates as skilled workers; and

Human relations school

Origins of job redesign

TYPES OF JOB DESIGN ACTIVITIES

Job rotation

Job enlargement

Job enrichment

WHO DOES WHAT IN HEALTH CARE?

Some unique characteristics of the health workforce

The professional health workforce in most countries is predominantly female. For example, in Australia women comprise 74.2 per cent of the total health care workforce and 92 per cent of the nursing workforce (AIHW 2004, pp 267, 260).

The professional health workforce in most countries is predominantly female. For example, in Australia women comprise 74.2 per cent of the total health care workforce and 92 per cent of the nursing workforce (AIHW 2004, pp 267, 260).

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Work design in health care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access