Assumptions are made about earlier decisions (before the change model is initiated) including analyses of what it would take to implement the decision.

Change theories may differ in how they are described, but their substance indicates a recognition by various theorists that change is in response to someone perceiving a need (the why); someone making a specific decision (the what); and someone planning an implementation of the decision (the how). These three steps are (hopefully) followed by communication, implementation, and follow-up actions to make change stick.

Recognizing the importance of this point, Schaller writes that the steps to change are to (i) define the gap between the present state and the ideal state (assuming someone has perceived a “why” before formulating the “what”); (ii) convene a group to initiate change (further defining the “what”); (iii) form another group to support the change and make suggestions (firming up the “how”); (iv) implement change; and (v) freeze the change (making sure the changes stick) (11).

Use of the word “freeze” to describe change that sticks is reminiscent of psychologist Kurt Lewin’s long taught theory of change. Lewin described people as being “frozen” in a certain way at any moment in time. When a person changes, he must unfreeze (thaw out), change, and then refreeze. He is then frozen with new or altered sets of beliefs or behaviors, until something causes him to unfreeze again (12).

Borrowing from Kathy’s earlier leadership book, we note that, “Life, then, is a series of learning experiences resulting in continual freezing, thawing, changing, and refreezing.” With the number and rapidity of change faced by those of us who work in healthcare today, it seems as if there isn’t enough time for one cycle to complete before another begins. We don’t have time to refreeze before the next thaw. The result is a messy state of affairs that can be described as a state of slush. Those of us who are attempting to survive and thrive in this icy, unformed flux may feel like a generation of “healthcare slush puppies” (13). (For those who may know it by another name, Slush Puppie is a brand name of an ice and flavoring treat similar to others that are known as Slurpies, Icees, or shaved ice sno-balls.)

Kathy’s frosty humor aside, the messiness of the healthcare environment and the changes occurring are welcomed by some, but dreaded and resisted by others. The chaos is resulting in real stress and discomfort for many individuals.

A large part of Dyad partnership work will be managing change. Understanding the steps to a change model (whichever you choose) is important for both leaders, because neither gets to opt out of the hard work of leading it. Every step into the next era of healthcare takes effort on the part of the Dyad partners and their teams.

Change is especially hard when it is imposed (from higher in the organization or from the government or a regulatory body). In fact, early researchers Blake and Mouton say imposed change sometimes succeeds, but more often fails (14). Even when an individual or group initiates change for themselves, it is seldom simple and not always successful. Some of the mistakes we have personally observed among colleagues tasked with making changes in (or transforming) healthcare areas for which they are the formal leader include

- Not clearly thinking through and articulating the why, how, what, and who.

- Not communicating well at every step of a change process.

- Not including the right people at every step.

- Not prognosticating who will be affected and where, who and what the resistance will be, and not planning tactics to mitigate this resistance.

- Not thinking through what might be collateral effects (after the fact these are called unforeseen consequences).

- Not realizing that what seems simple, nonimportant, or inevitable to some does not feel that way to others.

- Not considering what Thora Kron pointed out in 1971 as three obstacles to change in healthcare: emotions, habits, and self-satisfaction (15). Emotions can trump reason. Habits can be hard to break. An individual or group’s self-satisfaction with their place in the current world can cause active resistance to anything that endangers that status.

Our organization has practiced a defined change model for the last decade. We adopted the General Electric (GE) Change Acceleration Process (CAP) (16) as our facilitation tool for all organizational change. Our leadership team understands that change is not easy, even in the best of times. Foreseeing major upheavals in the healthcare world, an early decision was made to prepare the company for these. We purchased the CAP model, hired a national change team, and began educating change agents (leaders) throughout the system. Display 10-4 depicts the CAP methodology as it is practiced at CHI. In Display 10-5, Master Change Agent Jerri Brooks defines our organizational change management process.

Display 10-4 The CAP Methodology as Used at CHI

Change is effective and efficient when all components of the methodology are done well. The seven components of the CAP as purchased and adapted from GE and used by CHI are shared below. Included are brief definitions and examples of how these apply to the implementation of our Strategic Initiatives.

- Leading Change: Visible, active commitment by sponsors/champions and team members is critical to success. Leading change includes having CHI market-based organization leaders kick off and “own” the implementation of changes within their local organization, aligning key leaders, managers, and stakeholders around each project’s goals, and ensuring governance structures are in place to effectively lead the change.

- Creating a Shared Need: The reason for change is understood and shared. Through regular calls and meetings, both national and market-based organization leaders create understanding of the need for and shared benefits of the change.

- Shaping a Vision: The desired outcome of a change is clear, legitimate, widely understood, shared, and actionable. Market-based organization leaders develop their understanding of the vision and desired outcomes for successful project implementation. They then build common understanding and commitment through consistent communication within their local organizations.

- Mobilizing Commitment: Key stakeholders are identified, resistance is analyzed, and actions are taken to gain strong commitment. Onboarding sessions, ongoing assessments, training, communication, and site visits help gain the commitment of all stakeholders in the project implementation process.

- Making Change Last: Learnings are transferred throughout the organization, with consistent, visible, and tangible reinforcement of the change. Market-based organization leaders communicate successes and lessons learned during implementations, addressing stakeholders’ feedback and questions.

- Monitoring Progress: Success is defined with metrics and benchmarks to ensure accountability. Leaders regularly monitor progress toward project milestones and assess go-live success using operational metrics.

- Changing Systems and Structures: Management practices are aligned to complement and reinforce change. Leaders ensure that all policies, systems, structures, and processes are redesigned and aligned as needed with new project systems and processes. Effects on roles are identified and necessary changes implemented.

Organizational Communications: For CHI, we added a component to underpin the CAP model, focused on the importance of organizational communications. Multiple venues are put in place to ensure Dyad leaders are communicating with, and hearing from, appropriate stakeholders early, often, and throughout an initiative so that plans can be dynamically modified, based on customer needs.

From Jerri Brooks, MA, PMP, MCA, and Marilyn Jones-Davis, MHS, JD, Master Change Agents. Adapted from The General Electric CAP Model.

Display 10-5 Our Organizational Change Management Model

The sheer amount of change that healthcare organizations are facing is continuing and will continue to increase. Therefore, building the competency to lead and manage change is imperative for organizational success. Because of this, CHI adopted and adapted GE’s CAP to ensure the system has a common approach focused on the people side of change. Leaders have a robust change management competency to navigate, prepare, manage, and sustain the health of our business, communities, and patients. We define change management for Catholic Health Initiatives as a set of concepts, methods, and tools for leading and managing the people side of change. Through the use of CAP, we live out our core values of reverence, integrity, compassion, and excellence.

According to research from Prosci’s “Best Practices in Change Management” published in 2007, the top five contributors to successful change are (i) active and visible executive sponsorship; (ii) structured change management; (iii) frequent and open communication around the need for change; (iv) dedicated resources for change management; and (v) employee participation (17).

Change management in our company:

- Increases the organization’s capability for effective change

- Is applied by leaders and managers to help the organization and its employee’s transition from a current state to a desired future state

- Delivers methods and tools to help redesign processes and solve specific problems

- Uses a flexible/nonlinear model throughout the change process

- Facilitates commitment and behavioral change through team dialogue and action

- Increases the odds for and speed of successful change.

From Jerri Brooks, MA, PMP, MCA, Master Change Agent and Trainer.

As we mention above, there are a variety of change models, but most have similar steps. We are not advocating for a particular methodology, but do believe that an organization should select a model, educate formal leaders and employees on the steps to successful change, and insist that it is implemented and used throughout the company. Change will still be disruptive, but a defined way of proceeding with the disruption will minimize some of the chaos in these chaotic days.

Utilizing the steps of a change process as Dyads are introduced into the formal leadership hierarchy will make it more likely that this management model will be successfully adopted. The CAP steps we use illustrate this. In order to implement change that sticks, every step must be considered, planned for, and implemented. These include leading change, creating a shared need, shaping a vision, mobilizing commitment, making change last, monitoring progress, and changing systems and structures.

Changing the Leadership Paradigm: Implementing Successful Dyads

Leading Change

There needs to be a true commitment to this new type of shared leadership. The top executives in the organization must believe that co-management is the right model for defined departments, projects, service lines, or processes. They need to understand what they want to accomplish by implementing this significant departure from historical healthcare silos and hierarchies. They need to be ready to withstand criticism, angst, and resistance, even from those who voice unhappiness with the current lack of partnership between the silos.

Executives who support co-leadership should examine their own ability to accept increased influence from individuals currently not involved in the executive silo. Even leaders at the top will not escape some of the discomfort that will accompany the blurring of organizational silo boundaries.

We wrote this book partly because of our observation that executive leaders across the country are voicing a desire to implement shared leadership. We’ve watched as so-called Dyads are hired without consideration of what sharing really means. In some cases (granted, this is from the outside, so we may have inaccurate perceptions), it seems that two leaders are simply named Dyads, without thought of how to build their relationship, define individual roles, or provide basic management education to partners who have never managed. There does not seem to be consideration of the need to confront issues of differences in socialization and professional culture and to support two individuals who are embarking on a major job change during the chaos of healthcare transformation.

This change will fail if it is put in place without thoughtful planning and deliberate interventions to disrupt past relationship dysfunctions. Dyads won’t work, or at least won’t fulfill their potential of transforming organizations, if they are simply window dressing to appease specific stakeholders. The struggle for power between cultures will derail partnerships so that they won’t be able to lead the way to changing healthcare in America for everyone.

When executive leaders determine that Dyad leadership is a model to take their organizations into the next era, they must support it wholeheartedly. They show this support by verbalizing their belief in what Dyad leaders will be able to accomplish. They keep a close eye on, and are involved in, the change process steps. It’s essential that the Dyad leaders, their teams, the various organization silos, and the organization’s employees at all levels perceive that this is the top executive team’s preferred model for at least some (defined) management positions.

Creating a Shared Need

Once executive team members are convinced and committed to Dyad leadership, they will need to address the importance of other’s education about why the organization will benefit from co-leadership. Organizations possess an inertia that supports maintaining the status quo. This is true even when individuals or groups profess unhappiness or great discomfort with the way things are now. Kurt Lewin described resistance to change through a force field analysis, when he pointed out that the need to change (or perception of the need) must have greater force than the need to stay “frozen” the way we are now (12). Peter Senge reminded leaders that, “Although we are all interested in large scale change, we must change one mind at a time” (18). Since organizations have huge numbers of employees and stakeholders, this would be daunting if we believed every single person needed 1:1 convincing from executives. Fortunately, we agree with Malcolm Gladwell’s assertion that change occurs at certain dramatic moments known as “tipping points” (19). The tipping point for Dyad management will occur when multiple partnerships are implemented well and when they demonstrate an ability to unite previously siloed groups into teams working on shared goals.

Creating a shared need in an organization requires a diffusion of information about why Dyads will help lead into the future. This may require education as well as acknowledgement of what our current dysfunctions are because we operate in silos. The diffusion model we use in our organization includes education of formal leaders as part of helping them grasp the need to change. We also rely heavily on informal leaders for virtually every type of change. This is done through designating individuals as champions in our local markets and ensuring that they have the information and resources to share the need for change to their closest stakeholders.

You are reading this book, so we assume you perceive a need to at least consider a shared leadership model within your organization. You must have a compelling reason to change the healthcare habit of working in silos. This is probably because you can see that our industry is fragmented, is too costly, and does not provide the highest quality of care. You may feel your hospital is not providing the high value (low cost, plus high quality) you want to provide. Safety of your consumers may be a concern. Customer satisfaction scores may not be where you believe they should be, and employee and physician satisfaction may not be either. You may think this is the best way to lead a Clinically Integrated Network (CIN). You may have problems with variation in care that requires multidisciplinary teamwork. You may be concerned about mounting evidence that this variation is not beneficial to patients, and that some treatments and diagnostics we use not only are not always needed but are costly, and even harmful to individuals. All of these concerns might lead you to consider Dyad management.

Your conclusion might match ours: our professional cultural differences need to be bridged so that we can bring together the best thinking of diverse leaders to address long-standing problems, and one way to do this is to learn to share formal leadership.

We’ve learned that additional rationale for Dyad teams can be helpful when addressing leadership concerns of particular groups. For example, clinical groups are interested in knowing when one Dyad leader comes from their ranks, because they perceive that members of their profession have not previously been at tables where they believe they can and should influence change. (We’ve been surprised at how many professionals feel that their groups have been disenfranchised and disregarded, while other professions perceive those groups as powerful and controlling, while perceiving that their tribe has been disempowered!)

Whatever need your organization wishes to fill with Dyad leadership, it must become a shared need throughout the organization. That requires a dissemination plan, complete with disciples willing to spread the word that this is a good thing for diverse stakeholders.

Shaping a Vision

It’s important that leaders articulate what the organization will look like after Dyad leadership is implemented. If this isn’t done, there is no shared destination that people can move toward. It can’t be assumed that everyone sees the same picture of the future. Resistance to change occurs when different individuals and groups form their own visions.

These are actual comments we’ve heard from people when they first heard about this model in their organizations:

- “Finally. Doctors will be in charge, like we were when we started hospitals and before these MHAs were invented.” (Our interpretation of this statement is that this individual sees Dyads as a way to eventually move to a hierarchy where physicians are actually the sole top leaders. Incidentally, he also has a flawed historical lens because, while physicians led early academic centers, nurses were usually the superintendents of early community hospitals.)

- “Oh no. Here we go again. This is just another way to pacify physicians or pay money to an influential doctor, so he’ll support administration by swaying his peers. I’ll get a so-called partner who will simply give me all the work to do while he causes me more headaches with his lack of management skill and need to order people around.” (Our interpretation of this statement is that this manager is cynical about the organization’s commitment to actually leading together.)

- “This is great. Clinicians have been pushed out of the business side over time, and by combining the Docs and the RNs in teams, we will get the power to be heard. I see the day when we lead everything.” (Our interpretation is that this person sees benefit in two professional cultures working together but might not view the future as a place where teams, individual professionals, and leaders from all healthcare stakeholder groups are empowered to lead.)

While these comments illustrate views of the future through slightly different lenses, they have something in common. They envision the future leadership models as a “tweaking” of today’s hierarchy or dysfunctional relationships. They imply that power is a limited resource and something to be gained through positioning or by taking it away from someone else.

Our long-term vision is that Dyad leadership is a step toward other shared leadership models. We see the evolution of a system where learning to lead as two partners eventually leads to learning to lead in larger partnerships, too. Because that future is difficult to paint (early sketches have to be completed before murals can be done!) we share this verbal portrait of Dyad leadership: two leaders, peers from different professions, with different but complementary skills, education, and experience leading and managing multiprofessional teams to accomplish goals in support of the organization’s mission and vision.

Whatever your vision is for the formation of Dyads, it’s important to share it. Otherwise, ideas like those expressed above could undermine your organization’s journey toward a preferred future.

Mobilizing Commitment

Some people call this step “implementing an influence strategy.” You probably utilize a common influence strategy already, and this should be deployed as this model of management is rolled out. We mobilize commitment through change agents and designated champions. Our change (CAP) leaders, educators, human resource leaders, communication resources, and internal coaching teams have a part in developing these new partnerships. Change leaders reminded us to use our CAP steps. Educators develop leadership programs and courses for Dyad leaders. Human resource professionals help us with job descriptions, selections, and assessment of potential Dyad managers. Communication partners include references to Dyad partnerships throughout their various communication tools. Coaches work with individuals and Dyad pairs to help them work through their new roles and relationships.

Making Change Last

Dyads have great potential to lead organizational transformation, but only if the change to this type of leadership takes root in the organization. It is our intent, with this book, to share knowledge we’ve gained as a starting point for those pursuing this model. We intend to continue to share our successful (and not so successful) implementations of co-leadership and sincerely hope that other systems will do the same. As an industry, we can share best practices as we all integrate leadership models that will bring us together to change healthcare locally, as well as nationally, in the interest of individuals and communities.

Monitoring Progress

Implementing a new management model without planning how to determine its effectiveness is a mistake. As with any organizational change, there is a reason (a “why”) for deciding to lead differently. Co-leading is a departure from single-leader management. It isn’t competent leadership to put individuals and organizations through the cost or the disruption of this departure from the past without expected improvements in something (quality, cost, job satisfaction, or patient satisfaction). Goals for implementing Dyads should be documented and understood from the beginning. If they aren’t met, reasons for lack of progress should be analyzed, and appropriate interventions or changes must be made. On the other hand, when Dyad teams demonstrate that their partnership has met goals, or improved value to the organization, they should be emulated as best practice, and celebrated for their achievements.

Changing Systems and Structures

All healthcare organizations have systems and structures that support their current way of doing business. When Dyad leadership teams are initiated, these “underpinnings” of the company need to be examined and altered to support the new way of managing. If this isn’t done, there is high probability that 6, 12, 18, 24, or more months after implementation, executive leaders will declare that co-leadership simply doesn’t work, either as a concept or with the particular individuals selected to co-lead. New Dyad partners may be picked to replace the originals, or the model may be discontinued as an experiment that failed.

We’ve seen the latter occur and heard the statements:

- Well, we tried, but formal leadership just doesn’t work with two people. There must be one accountable manager making final decisions for every process, project, or department.

- I knew physicians couldn’t learn to do the hard work of management or figure out how to be part of a team.

- That was just the “flavor of the month,” another hare-brained, follow-the-pack management idea.

Executives who believe that this model of leadership could bridge traditional cultural divides must invest time considering what environmental changes support or threaten its success. Then, they need to remove or mitigate any identified barriers to success.

We’ve identified the need for appropriate selection of partners, evaluation of individual strengths and weakness, availability of individual and Dyad education and coaching opportunities, importance of team building, and the need to openly address cultural differences, as well as the “little things” that can add up to an environment not conducive to partnership development. Every organization probably has other systems and structures that could pose challenges to Dyad leadership. Are there committee structures that need to change to allow appropriate Dyad participation? Will executive pay practices be perceived by designated “equal partners” as unfair, inequitable, or illogical? Will these cause resentment between co-leaders if not addressed or rationally explained? Are there hiring practices that discourage selection of people who could best succeed in these roles? Are there policies or rigid hierarchical-based procedures that will prevent Dyad leaders from making timely decisions or coordinated change implementations together? Are there cultural barriers executives need to address to “smooth the way” for Dyad leaders?

Implementation of formal Dyad leadership partnerships in the place of individual leaders should be considered like any major organizational change. This is the responsibility of executives who choose to put them into practice.

From Change to Transformation

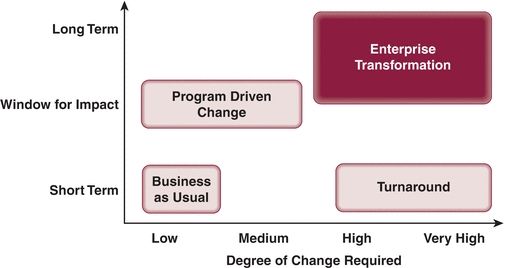

As we mentioned before, Dyad leadership as a management structure is a beginning step in transforming an organization. Transformation is more than “garden variety” change. Figure 10-1, adapted from a slide from the consulting firm Accenture, is an excellent illustration of how much change is necessary to actually transform an organization. As it depicts, change occurs continually in small increments to make short-term alterations. This is labeled “Business as Usual.” A greater amount of change must occur when an organization is in a “turnaround” state.

FIGURE 10-1 Types of transformation. (Adapted from Accenture with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree