Chapter 5 Ways of looking at evidence and measurement

Learning outcomes for this chapter are:

1. To explore the dimensions of evidence and measurement in midwifery

2. To introduce some of the common terms used in research, in both qualitative and quantitative methods

3. To outline the use of epidemiology in gathering evidence

4. To identify some of the pitfalls in the evidence-based movement.

Measurement is crucial to the way we practise. It provides us with the basics for learning about and improving our understanding of what we do. It helps us to assess the safety and effectiveness of our practice. The purpose of this chapter is to provide an introduction to the use of measurement and seeking truth in midwifery practice and decision-making. Much of our current practice rests on both the evidence of epidemiological research and the findings of qualitative studies. You will be introduced to some of the most common epidemiological methods of research as well as some of the methods used to understand the quality and meaning of the practice of midwifery and the quality and meaning of childbirth for women. These examples of the way we measure our experiences appear, on the surface, to contradict each other. On the one hand, quantitative research such as epidemiology provides the story of populations or groups of people in the language of averages and statistically derived measures. Qualitative research, on the other hand, provides us with the story of the individual who is inextricably connected to the influences of their own context, and is only one individual in the population sample of the epidemiologist. In midwifery, both quantitative and qualitative exploration enriches our understanding of what we do. This chapter provides a summary of and an introduction to the many ways of measuring experience. It is intended to be used as an introductory tool for understanding the basics of evidence-based practice. In measuring anything, it is always important to be aware that simply through quantifying something we are in danger of disregarding, devaluing or even denying the very thing we are trying to measure.

INTRODUCTION

Some ways of knowing have traditionally occupied spaces at the edge of the dominant vision, the same kinds of spaces as are filled by the lives and experiences of the socially marginalised, including women. Thus, neither methods nor methodology can be understood except in the context of gendered social relations. Understanding this involves a mapping of how gender, women, nature and knowledge have been constructed both inside and outside all forms of science (Oakley 2000, p 4).

Inquiry is based on the recognition of certain connections. It is important always to be mindful that separating the knower from what is known implies a separation of one’s self from another person and also implies the separation of the researcher from the subject of research (Reason 1988). The connection between understanding in the scientific and biological domain, and the experience we bring from our family, our practice, our social and political contexts, together with our use of language, is the reason we can expect to have different and multiple understandings of the world. We make sense of facts and select and organise all our observations based on the influences of previous learning and practice. Drawing stories from our reservoir of experiences and social contexts connects us through language and metaphor to understand the science behind midwifery. Understanding biological systems depends on a multiplicity of understandings, explanations and connections (Fox Keller 2002).

SEEKING TRUTH

Legal methods of arriving at the truth need little explanation. Here something is deemed to be true because it can be substantiated through authoritative testimony. The expert witness is seen as an authority and an expert in the subject under examination. Up until the past 15 years we were familiar with the use of the word ‘evidence’ in relation to legal method. However, with the widely accepted move in medicine to evidence-based medicine (EBM), the word ‘evidence’ has taken a much more prominent position in the scheme of things. Box 5.1 walks you through an ethical argument in addressing the question: ‘Is evidence the same as research?’

Box 5.1 Is evidence research?

Is evidence the same as research?

• In order for something (e.g. data) to be construed as ‘evidence’ it must be judged to be relevant and have a strong conclusion. This requires subjective interpretation, from the viewpoints of several individuals.

• Evidence itself does not constitute truth; rather, evidence plays a role in determining what is believed to be true. For example, in legal terms the evidence used to support various theories of what actually happened at the time of a crime is compared until one of the theories begins to hold more weight than the others, and, on the basis of the available evidence, is considered the most likely to be true.

• Consider how the selection of evidence to support conclusions is negotiated and debated. It is affected by social and other forces such as power, coercion and self-interest of one negotiator, or group of negotiators, vis-à-vis another. These forces then may have an impact on which conclusions or theories are ultimately selected as most likely to be true.

• Now consider the common practice of applying research data from studies conducted exclusively on male research participants, to female patients. The idea that data from men can be applied directly to women reflects a reductionist view of human physiology and a previously held social bias that took women’s health to be an offshoot of men’s health.

• Hence, evidence is a status conferred upon a fact, reflecting, at least in part, a subjective and social judgement that the fact increases the likelihood of a given conclusion being true. For any given set of phenomena, there may be many available facts that could count as evidence for more than one conclusion or theory. However, only some facts will be deemed as evidence for one successful conclusion or theory, which itself is chosen from among several options.

• Thus, evidence is not, as EBM implies, simply research data or facts but a series of interpretations that serve a variety of social and philosophical agendas.

(Based on an argument proposed by Gupta M 2003.)

One of the most widely accepted methods of searching for truth in midwifery is through scientific method or research. Searching for truth using scientific research methods involves the systematic study of phenomena and the relations between and among phenomena using agreed rules or accepted methodologies. The systematic collection, analysis and interpretation of data minimises the contamination of results from external factors (known as bias) (Kirkevold 1997).

There are two main schools of thought on how scientific method should proceed.

• On the one hand, it is believed that the theory and hypothesis should be developed before the research is undertaken. This is known as deductive method. It follows the thinking of Karl Popper (1972) that scientific knowledge is gained through the development of ideas and the attempt to refute them with empirical research. The dominant philosophy underlying quantitative scientific method is positivism. Positivism assumes that phenomena are measurable using the deductive principles of the scientific method. That is, the investigator starts with a theory and a hypothesis that is tested by the data (deduction).

• The other school of thought is that research should precede theory and not be limited to a passive role of verifying and testing theory; rather, it should help to shape the development of theory (Bowling 2002) by the process of induction.

Both these strategies are used to develop the knowledge of midwifery.

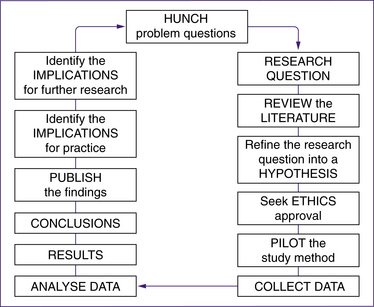

Regardless of the method of research, this basic formula sets out the cycle of events that occur in a research process (Fig 5.1).

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

Qualitative research contributes to the understanding of social aspects of health issues, through direct observation of the nuances of social behaviour (Green & Britten 1998; Pope & Mays 2000). Qualitative research can investigate practitioners’ and patients’ attitudes, beliefs and preferences, and the whole question of how evidence is turned into practice. The value of qualitative methods lies in their ability to pursue systematically the kinds of research questions that are not easily answerable by experimental methods. Rigorously conducted qualitative research is based on explicit sampling strategies, systematic analysis of data, and a commitment to examining counter-explanations. Ideally, methods should be transparent, allowing the reader to assess the validity and the extent to which the results might be applicable to their own clinical practice. Qualitative research does not usually produce numerical rates and measures (Green & Britten 1998). Researchers who use qualitative methods seek a deeper truth (Greenhalgh & Taylor 1997). They aim to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena using a holistic perspective that preserves the complexities of human behaviour (Black 1994). The research often provides us with a picture of ‘behind the scenes’, how people are feeling, or what other forces are at work that may not be discovered in a quantitative investigation of facts.

An example of the ‘behind the scenes’ behaviour that affected the introduction of evidence-based leaflets into maternity hospitals in the United Kingdom was recorded by Stapleton et al (2002) when they undertook a qualitative study beside a randomised controlled trial (RCT) by O’Cathain et al (2002). In the experimental study, the researchers concluded that in everyday practice, evidence-based leaflets were not effective in promoting informed choice for women using maternity services (O’Cathain et al 2002). The qualitative study (Stapleton et al 2002) mounted alongside this RCT provided a rich insight into what was happening with the information leaflets, and found that the way in which the leaflets were disseminated affected promotion of informed choice in maternity care. The qualitative study provided the evidence for ‘behind the scenes’ and the bullying and coercive behaviours that had become a normal way of doing things in these maternity units. The culture into which the leaflets were introduced supported existing normative patterns of care and this ensured informed compliance rather than informed choice (Stapleton et al 2002).

Overview of qualitative methods

Ethnography

• Data are gathered through participant observation and interviews, and the researcher interprets the cultural patterns observed.

• The sample is taken from a cultural group living in the phenomenon. These are known as the key informants and the general informants. The key informants are those with special knowledge who are prepared to teach the researcher.

• The analysis is undertaken on field notes and observations, and meaning is sought from cultural symbols in the informants’ language.

Narrative

Narratives help to set a person-centred agenda and challenge received wisdom, and they may generate new hypotheses. Narratives offer a method for addressing existential qualities such as inner hurt, despair, hope, grief and moral pain, which frequently accompany, and may even constitute, people’s illnesses (Greenhalgh & Hurwitz 1999).

• Data-gathering involves collecting the story the respondent has to tell.

• The sample is a convenience sample.1

• The analysis of the narrative is an interpretive act; that is, interpretation (the discernment of meaning) is central to the analysis of narratives. Actual transcripts are presented in the results of narrative research.

Historical research

• The data consist of a systematic compilation of data regarding people, events and occurrences in the past.

• The sample tries to identify all data sources.

• The analysis involves the validity of external criticism; reliability delineates data sources by internal criticism. The reader ‘hears’ the narrator’s ‘voice’ and ‘sees’ the actions in the story with the eyes of an ‘internal’ or ‘external’ focaliser, who may or may not be identical to the narrator (Norku 2004).

Grounded theory

Grounded theory aims to find underlying social forces that shape human behaviour. The theory emerges or is generated from the data in a manner that means most hypotheses and concepts not only come from the data, but are systematically worked out in relation to the data during the course of research (Strauss & Corbin 1998).

• Data consist of interviews and skilled observations of individuals interacting in a social setting.

• The sample is purposive—the researcher deliberately samples a particular group or setting of people who are experiencing the circumstance.

• During analysis, the researcher’s task is to sift and decode the data to make sense of the situation, events and interactions observed. Often this analytical process starts during the data-collection phase. Variants of content analysis involve an iterative process of developing categories from the transcripts or field notes, testing them against hypotheses, and refining them (Mays & Pope 1995; Strauss & Corbin 1998).

Other methods

Other qualitative research methods include:

• documents—study of documentary accounts of events, such as meetings

• passive observation—systematic watching of behaviour and talk in naturally occurring settings

• participant observation—observation in which the researcher also occupies a role or part in the setting, in addition to observing

• in-depth interviews—face-to-face conversation for the purpose of exploring issues or topics in detail. Does not use preset questions, but is shaped by a defined set of topics.

• focus groups—method of group interview that explicitly includes and uses the group interaction to generate data (Greenhalgh & Taylor 1997).

Questions to ask

Mays and Pope (1995) suggest the following questions to ask of qualitative studies:

• Has the study contributed to our knowledge?

• Was the research question clear?

• Would a different method have been more appropriate? Was the design appropriate for the question?

• Is the context adequately described?

• Was the sampling strategy clearly described and justified?

• How was the fieldwork undertaken? Was it described in detail? Could the evidence (fieldwork notes, interview transcripts, recordings, documentary analysis, etc.) be inspected independently by others; if relevant, could the process of transcription be independently inspected?

• Were the procedures for data analysis clearly described and theoretically justified? Did they relate to the original research questions? How were themes and concepts identified from the data? Was the analysis repeated by more than one researcher to ensure reliability?

• Was there an audit trail, so that another researcher could repeat each stage of the research?

• Was enough of the original evidence presented systematically in the written account to satisfy the sceptical reader of the relation between the interpretation and the evidence? (For example, were quotations numbered and sources given?)

Box 5.2 How to search

How to search for a paper on Medline or the Cochrane library:

1. To look for an article you know exists, search by text words (in title, abstract, or both) or use filed suffixes for author, title, institution, journal and publication year.

2. For a maximally sensitive search on a subject, search under both MESH headings (exploded) and text words (title and abstract), then combine the two by using the Boolean operator ‘or’.

3. For a focused (specific) search on a clear-cut topic, perform two or more sensitive searches as in step 2, and combine them by using the Boolean operator ‘and’.

4. To find articles that are likely to be of high methodological quality, insert an evidence-based quality filter for therapeutic interventions, aetiology, diagnostic procedures or epidemiology, and/or use maximally sensitive search strategies for randomised trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

5. Refine your search as you go—for example, to exclude irrelevant material, use the Boolean operator ‘not’.

6. Use subheadings only when this is the only practicable way of limiting your search, as manual indexers are fallible and misclassifications are common.

7. When limiting a large set, browse through the last 50 or so abstracts yourself rather than expecting the software to pick the best half dozen.

(Source: Greenhalgh 1996)

Box 5.3 Definitions

Some common terms used in research:

• case studies—focus on one or a limited number of settings; used to explore contemporary phenomena, especially where complex interrelated issues are involved. Can be exploratory, explanatory or descriptive, or a combination of these.

• consensus methods—include Delphi and nominal group techniques and consensus development conferences. They provide a way of synthesizing information and dealing with conflicting evidence, with the aim of determining the extent of agreement within a selected group.

• constant comparison—iterative method of content analysis where each category is searched for in the entire data set and all instances are compared until no new categories can be identified.

• content analysis—systematic examination of text (field notes) by identifying and grouping themes and coding, classifying, and developing categories.

• epistemology—theory of knowledge; scientific study which deals with the nature and validity of knowledge.

• field notes—collective term for records of observation, talk, interview transcripts, or documentary sources. Typically includes a field diary which provides a record of the chronological events and development of research as well as the researcher’s own reactions to, feelings about, and opinions of the research process.

• Hawthorne effect—impact of the researcher on the research subjects or setting, notably in changing their behaviour.

• naturalistic research—non-experimental research in naturally occurring settings.

• purposive or systematic sampling—deliberate choice of respondents, subjects or settings, as opposed to statistical sampling, concerned with the representativeness of a sample in relation to a total population. Theoretical sampling links this to previously developed hypotheses or theories.

• reliability—extent to which a measurement yields the same answer each time it is used.

• social anthropology—social scientific study of peoples, cultures, and societies; particularly associated with the study of traditional cultures.

• triangulation—use of three or more different research methods in combination; principally used as a check of validity.

• validity—extent to which a measurement truly reflects the phenomenon under scrutiny.

(Source: Pope & Mays 1995)

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

The aim of evidence-based practice, to quote Professor David Sackett, is ‘the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients … the integration of individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research’ (Sackett & Cooke 1996, p 535). In other words, it is the combination of clinical judgement and clinical practical experience with information we gather to help us learn.

The following five steps in putting evidence into practice are based on the work of Sackett et al (1996):

1. Fit what you want to know into a question that can be answered.

2. Go looking for the best research to answer it.

3. Critically estimate the research for how close it is to the truth and whether it could be clinically useful.

4. Try to use the suggestions in practice.

In The New Midwifery, Professor Lesley Page describes evidence in terms of ‘a process of involving women in making decisions about their care and of finding and weighing up information to help make those decisions’ (Page & McLandish 2006, p 360). The five steps to evidence-based midwifery (Box 5.4) were adapted by Professor Page from the original work in this area undertaken by Sackett and colleagues in 1996 (Sackett et al 1996).

Box 5.4 Page’s five steps

1. Find out what is important to the woman and her family.

2. Use information from the clinical examination.

3. Seek and assess evidence to inform decisions.

(Source: Page 2006)

In step 3, seeking and assessing evidence, the original authors added that it is important to decide how valid something is. In other words, how close to the truth is it? It is also important to find out how useful it is—that is, how applicable to practice is the evidence? One thing to remember is that evidence-based midwifery should never be a ‘cookbook’ approach to what we do. The evidence that we bring to practice from the literature or from research should only ever inform our practice, not replace it; and it should always be taken along with a woman’s individual preference for a clinical decision (PageMcLandish 2006; Sackett & Cooke 1996).

• Does it involve a Population of interest, or does the population closely resemble the one you want to understand?

• Is the Intervention or treatment relevant for your area of interest?

• Is the Comparison group appropriate?

This is known as the PICO method (see Box 5.5). The appendix at the end of this chapter lists questions to ask in evaluating a clinical guideline.

Evidence-based everything

Evidence-based obstetric care is a relatively new concept, which had its origins in the early 1970s … this was a shift away from opinion-based obstetrics, which up until then had been the dominant paradigm. (King 2005)

The ‘evidence-based’ (EB) prefix moved with discreet political correctness over the years and attached itself not only to medicine, but more inclusively to EB practice, EB decision-making and EB healthcare. As the originators of the evidence-based movements concede, ‘it engenders enthusiasm, anger, ridicule and indifference amongst people’ (Sackett & Cooke 1996). Some have even suggested that evidence-based medicine (EBM) demonstrates the ‘scientific chauvinism of the English’ (Halliday 2000).

There are many claims for and against EBM. It is important for midwives to spend some time reflecting on its pros and cons. Evidence-based care features very strongly in our search for evidence and measurement in practice (Chalmers 1989).

Those who question the authority of EBM believe that only studies with positive results get published, or that the art of patient care is threatened. Some critics say that systematic reviews may be ‘pooling ignorance as much as distilling wisdom’ (Naylor 1995, p 840), that ‘medical muddling’ is a profitable business and that the proliferation of new tests, devices and drugs continues at an unprecedented pace (Naylor 1995). Others concede that life would be very much simpler if new technologies could be appraised in rigorous studies with clinically relevant endpoints and data to guide practice (Chalmers 1989). Imagine if the question of the safety of hospital over home birth had been tested with relevant, well-designed studies of safety and satisfaction before women were expected to move from home to hospital for birth.

Box 5.6 EBM

One opinion on the EBM movement is that:

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) became the buzzword of the 1990s. Proponents of the method often recommend it with the zealousness of those who have received religious enlightenment. (Traynor 2000)

Some followers of EBM have even stated that:

medicine has continued on a very dark and ill-informed path over the centuries, in fact, when the teachings of Galen superseded Hippocrates’ first aphorism, ‘life is short’, sixteen centuries of dogma followed, and scientific rigour was not applied to medicine again until the appearance of Archie Cochrane and his contemporaries in the 1950’s! (Halliday 2000)

own beliefs and give rise to a hierarchy in which some types of evidence are valued above others’ (Stewart 2000). Many midwives would agree with the statement that ‘The power of authoritative knowledge is not that it is correct but that it counts’ (Jordan 1993, p 58).

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL METHOD

The foundation and primary focus of evidence-based care is within the specialty of medical epidemiology, ‘to ensure the practice of effective medicine, in which the benefits to an individual patient or population outweigh any associated harm to that same patient or population’ (Muir Gray 1997, p 3). The underlying belief is that meaning can be discerned from population patterns and that a relation exists between mathematics and material reality. The epidemiologist’s focus of study is the whole population, in which outcomes are described in averages and percentages, rates and risks. Then the science of chance is applied in the form of a statistical framework that gives the reader an indication of the measurement error or the uncertainty with which the result is believed to be true. This is better known as the ‘confidence interval’ (Jolley 1993). Epidemiology seeks to provide answers through the analysis of accumulated results of hundreds or thousands of comparable cases in population samples. The language of mathematics is used to describe the findings in terms of ‘probability’ and ‘risk’. Such answers, arrived at through studying population samples in randomised trials and cohort studies, cannot be mechanistically applied to the individual. ‘In large research trials the individual participant’s unique and multidimensional experience is expressed as (say) a single dot on a scatter plot to which we apply mathematical tools to produce a story about the sample as a whole’ (Greenhalgh 1999, p 324).

In other words, the answers that we gain from doing research at a population level tell us about the general population in averages and frequency measures. They do not tell us the story of the individuals who took part. In asking ‘What works?’, we are suggesting that research will show us how to do things the best way. The danger here is that we may unwittingly focus on very narrow ‘evaluative’ studies—that is, studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of an intervention, such as the randomised controlled trial (RCT), when in fact information from a whole range of types of studies, answering a variety of questions, may be more useful. (See the story of the information leaflets earlier.) In reality we practise within a complex and mostly unpredictable reality in which learning from trial and error may be an important way to make progress.

At the turn of the 20th century, epidemiological research began to explicitly incorporate social science perspectives related to health data that could inform public policy. One of the first substantial prospective epidemiological analyses to be undertaken was a study of the socioeconomic and nutritional determinants of infant mortality in the United States in 1912, by Julia Lathrop (Kreiger 2000). As sociologist Ann Oakley pointed out, the history of experimentation and social interventions is ‘conveniently overlooked by those who contend that randomised controlled trials have no place in evaluating social interventions. It shows clearly that prospective experimental studies with random allocation to generate one or more control groups is perfectly possible in social settings’ (Oakley 1998, p 1240). The usefulness of the population-based results of an RCT depends on the translation of the concepts and measures used to describe groups of people into a language that can inform the decisions of an individual (Steiner 1999).

The RCT is currently considered to be the orthodox and ‘gold standard’ scientific experimental method for evaluating new treatments. The ethical basis for entering patients in RCTs, however, is under debate. Some doctors espouse the uncertainty principle whereby randomisation to treatment is acceptable when an individual doctor is genuinely unsure which treatment is best for a patient. Others believe that clinical equipoise, reflecting collective professional uncertainty over treatment, is the most sound ethical criterion (Weijer et al 2000). The scientific principles that are applied to the design and conduct of primary research, such as the RCT, are also applied to secondary research, such as the systematic review (Chalmers et al 1992). Many regard epidemiology as ‘an arcane quantitative science penetrable only by mathematicians’ (Grimes & Schulz 2002). However, it must be pointed out that ‘statistics is at most complementary to the breadth and judgement’ of the knowledge gained from epidemiological research (Jolley 1993, p 28).

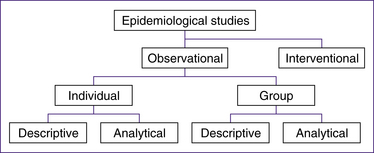

Figure 5.2 outlines the kinds of studies you will encounter in the scientific literature, both medical and midwifery, that are based on the epidemiological method.

In order to find where the ‘best evidence’ is to support our practice we are encouraged to give research studies a ranking from the highest level, or the ‘gold standard’, to the lowest level of research evidence. These rankings are made explicitly on the ranking of research methods from the most reliable to the least reliable. This ‘evidence hierarchy’ provides an initial screening test as to whether data from research studies are derived from methods that are more likely or less likely to guide readers towards truthful conclusions (Gupta 2003). (Further discussion

on this topic, and current debates, definitions and controversies, can be found on the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine website at www.cebm.net/.)

Experimental trials are limited when the study size is too small to detect rare or infrequent adverse outcomes, or when the outcome of interest is long term and the trial would need to continue for an improbable length of time. In all these cases, observational studies may be considered more practical (Black 1996). Observational studies may be most valuable where randomising people to an intervention is inappropriate (Black 1996)—for example, randomising women to having water for birth or to having an elective caesarean section is inappropriate and also disregards the ‘effect that choice itself has on therapeutic outcome’ (McPherson 1994).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree