CHAPTER 2 Ways of knowing for clinical practice

Introduction

A key goal of clinical education is to foster the development of the learner’s knowledge base. The first task in pursuing this goal is to understand the nature of knowledge. In this chapter knowledge is presented as a sociocultural, historical construction embedded in the language, discourse and practice of the setting and time in which it is used. This is illustrated by several examples of how knowledge has been influenced, along with practice, by changes in political, social, educational and cultural circumstances in different eras. It is argued that a deeper understanding of the way knowledge is constructed and used in practice is essential for good practice and for sound clinical education. The importance of making explicit our practice epistemology (i.e. the knowledge and ways of knowing underpinning practice) in practice and education is a key argument presented in this chapter and in previous work (Higgs et al 2008c, Richardson et al 2004). See also Chapter 1 of this book where knowing and learning in social frameworks is discussed.

History, practice, education and knowledge

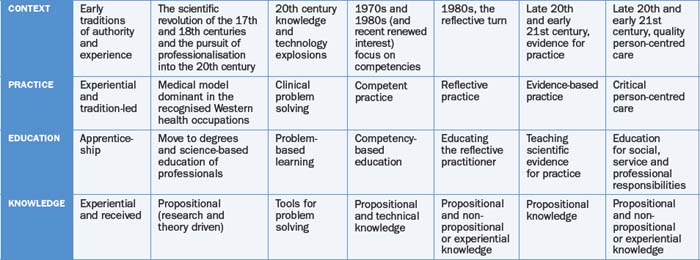

History provides us with an understanding of the way current practice and knowledge has emerged and the factors influencing this development. Education of health professionals has both responded and contributed to this evolution. In particular, clinical education has played an important part in the shaping of practice knowledge and knowledge of what it means to be a health professional. In considering the origins and evolving influences on the nature of professional practice and education in the health sciences Higgs and Hunt (1999) identified the following stages in this evolution.

a The apprentice

Traditional healthcare workers operated and learned in an apprenticeship model. They learned in the workplace setting, studied the master’s art, progressed through simple, highly supervised tasks to more complex and independent tasks, became independent practitioners and, potentially, masters themselves. The apprenticeship system focused on the practice knowledge, craft and art, and the practical role of the healthcare worker. The quality of this system ranged from poor, with unquestioned or required adoption of ill-founded practices and knowledge reflected by poor role models, to excellent, where the apprentice learned from expert role models who offered individual, knowledgeable tuition, direct demonstration and quality supervision. Such education persisted for many years in hospital-based programs (Twomey 1980) and early tertiary education programs, where knowledge of experienced practitioner educators was passed on, rather uncritically, to the next generation. The main concern with this approach is the limitation of the novice’s development to the mentor’s level of expertise.

b The health professional

Traditionally, established professions such as medicine have owned a body of knowledge, operated in a service mode under a code of professional conduct, and sought to establish the quality of performance through self-regulation. The professionalisation of other health disciplines in the first half of the twentieth century involved the desire to attain professional status and credibility, the pursuit of professional attributes and (commonly) the adoption of the medical model along with justification of the discipline’s professional knowledge and skills through (medical) scientific research and priorities. The model of practice adopted was one of professional activity comprising instrumental problem solving, made rigorous by the use of scientific theory and technique. Educational programs of this era emphasised socialisation into the professional role and the acquisition of the knowledge, skills and attitudes needed to enter the profession as capable beginning practitioners.

c The clinical problem solver

Learning to cope with the knowledge and technology explosions and the threat of rapid knowledge obsolescence in the second half of the twentieth century saw an increased emphasis on the skills of problem solving, with a diminishing emphasis on knowledge acquisition. For some, this cognitive skill orientation was over-emphasised and the reliance on problem-solving skills in the absence of a sound knowledge base was criticised. Research in the area of clinical reasoning and problem solving (Norman 1988), for instance, supported the essential link between knowledge and reasoning, while Boshuizen and Schmidt (1992, 1995) identified the importance of concurrent development of domain-specific knowledge and cognitive skills to use this knowledge as part of the process of developing clinical reasoning expertise. (See Chapter 4.)

e The reflective practitioner

Schön’s (1983) model of the reflective practitioner raised concerns about the growing gaps between the practical knowledge and actual competencies required of practitioners in the field and the research-based (propositional) knowledge taught in professional schools. Reflective practice, he argued, was needed to deal with the uncertainty of professional work and workplaces where workers frequently face complex goals and unpredictable ill-defined problems. The reflective practitioner model has attracted both criticism and acclaim. It has certainly provided the impetus for a wider exploration of the nature, importance and scope of reflective practice within client-focused healthcare (e.g. Eraut 1994, Fish & Coles 1998, Fulford et al 1996).

f The scientist practitioner

The latter part of the twentieth century saw a growing concern with the lack of scientific foundation for aspects of healthcare in both the emerging and the more established health professions. The scientist–practitioner model epitomises a commitment of professional groups to scientific rigour (James 1994) and reflects the escalation of research into the scientific evidence for practice that has characterised recent decades. The global trend of evidence-based practice is encapsulated in Twomey’s (1990, p 83) argument that clinicians must be able ‘to adequately justify their treatment methods [because] the community demands a high quality of care and a cost-efficient system’.

g The interactional, person-centred professional

Various models of healthcare and health professional education are emerging in recent decades to counter and broaden the narrow focus in many arenas on the scientific definition of evidence for practice. These models emphasise person-centred care grounded in critical social science principles of emancipatory practice and social responsibility (e.g. Trede & Haynes 2008), and the interactions between health professionals, their partners in healthcare and their environment. Underpinning person-centred healthcare lies a model of practice that supports the emancipation rather than the manipulation of patients. ‘Including patients in the decision-making process promises to result in more realistic and appropriate treatments, reduced patient concerns and complaints, and better, sustainable health outcomes, and increased patient and clinician satisfaction’ (Trede & Higgs 2003, p 66). A critical approach to thinking and emancipatory knowledge is required for this practice approach. A similar emphasis on people and their relationships is contained in a social ecology model of health practice (and education) introduced by Higgs and Hunt (1999, p 44) which embeds some of the strengths of previous models in the interactivity of social ecology.

Table 2.1 summarises these trends and illustrates the powerful interrelationship between knowledge and context.

Knowledge and practice as sociocultural, historical constructions

From the discussion above it is evident that the nature of practice, education and how professional practice knowledge is defined and used are influenced by the sociocultural and historical context of that period of history (see also Larsen et al 2008). Consider, for instance, the following historical influences on practice. In 1986 the World Health Organization’s Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) emphasised the need to develop strategies ‘to bring about changes in the physical, social and economic environment in which people live’ (Donovan 1995, p 2). One such strategy was to increase the focus on community and environmental health with a greater emphasis on the prevention of disease and the promotion of good health (Higgs et al 1999), as well as the provision of quality acute and chronic healthcare. Lawson et al (1996, p 11) reported a global shift ‘away from the cure of individuals presenting for service towards the prevention of illness in populations and the strengthening of the community’s capacity to deal with its own health’. In recent years the influence of the communications and information revolution has made an enormous impact on both health practices (e.g. telehealth, and consumer access to self-help information) and the way knowledge is perceived and disseminated. University students, for instance, learn to critically appraise the source and credibility of information widely available on the web.

The context for healthcare in the twenty-first century (Fish & Higgs 2008) encompasses both growing fragmentation and uncertainty, and an unprecedented level of globalisation with increasingly blurred national boundaries, problems of world aid and the complexity of balancing economic demands with decreased public funding resources, all of which have implications for consumers and providers (Higgs et al 1999). Bauman’s (2000, 2005) term ‘liquid modernity’ epitomises the mercurial and unsettled spirit of life in the West in the twenty-first century. Alongside these influences is the ‘dot.com mentality’ which emphasises short-term abstract fixes rather than long-term relationships with people and, as Sennett (2005) argues, commitment to humane thinking and continuity of care are sidelined. In this age, established knowledge has a short life, and tradition and experience are no longer valued. Fish and Higgs (2008) argue that the ‘now’, ‘same’ (cloning) and external scrutiny focus of this age needs to be countered by attention by professionals to being able to present their moral position, to work with ‘transparency and integrity, and exercise their clinical thinking and professional judgement in the service of differing individuals, while making wise decisions about the relationship between individuals’ privacy and the common good’ (p 21). To achieve these outcomes propositional knowledge is inadequate and experiential knowledge (as presented below) is essential, along with changing approaches to what knowledge is and how it is constructed. The rules of the physical sciences knowledge world need to be accompanied by ways of knowing that enable the humanity, nuances and human interests of the social world to be appreciated.

To further illustrate this contextually driven evolution of practice and knowledge consider the example of two professions, physiotherapy and occupational therapy. Pynt et al (2008) discuss the historical antecedents of physiotherapy (such as the use of therapeutic manipulation in ancient Egypt), and the more recent evolution of physiotherapy from the time the occupation gained its identity in Western healthcare to the present time. In their interpretation of the evolution of modern physiotherapy practice, Pynt et al (2008) identify four practice eras.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree