Watson’s Philosophy and Science of Caring in Nursing Practice

D. Elizabeth Jesse and Martha Raile Alligood∗

Caring in nursing conveys physical acts, but embraces the mindbodyspirit as it reclaims the embodied spirit as its focus of attention. It suggests a methodology through both art and aesthetics, of being as well as knowing and doing. It concerns itself with the art of being human. It calls forth from the practitioner an authentic presencing of being in the caring moment; carrying an intentional caring-healing consciousness… . Nursing becomes a metaphor for the sacred feminine archetypal energy, now critical to the healing needed in modern Western nursing and medicine.

History and Background

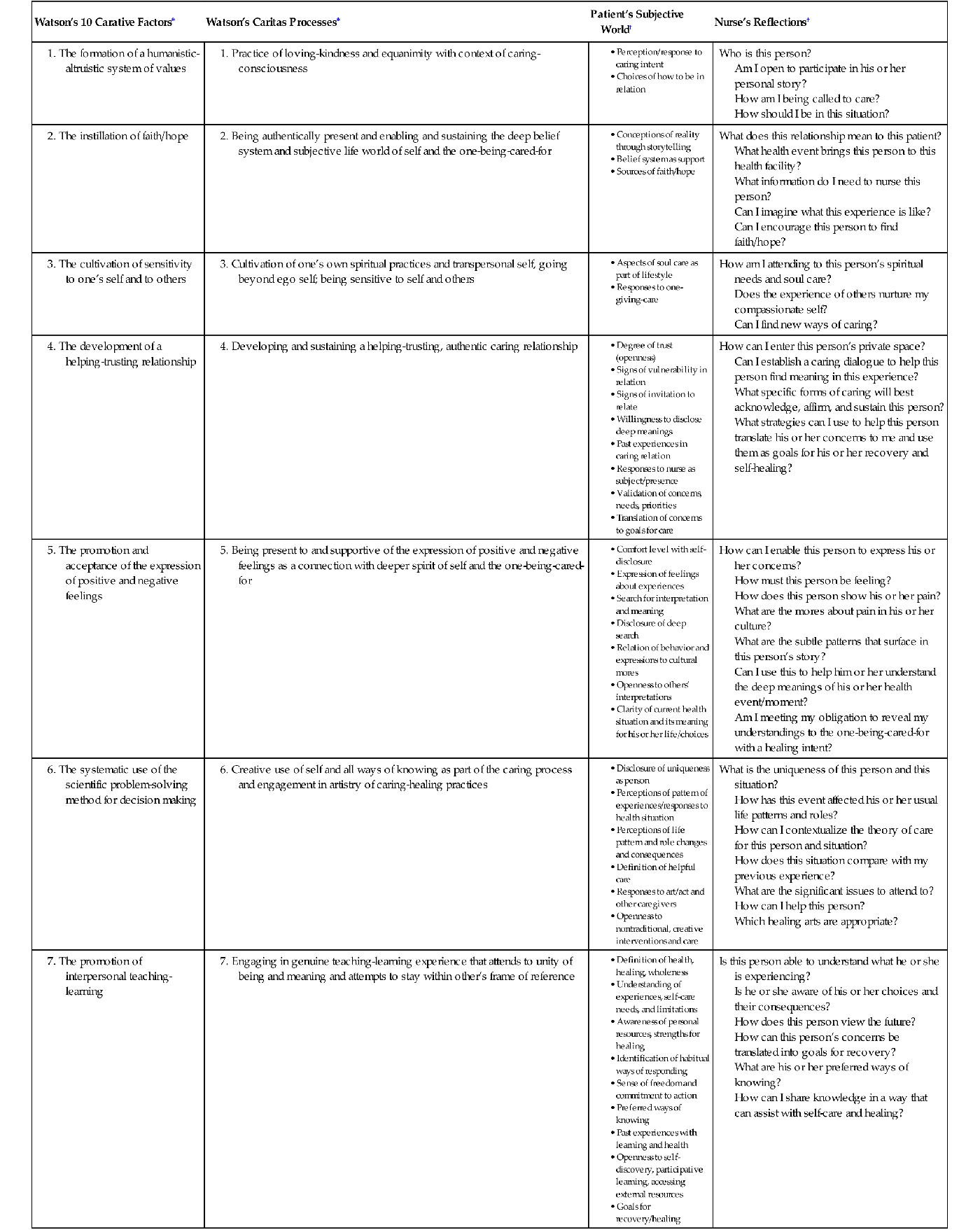

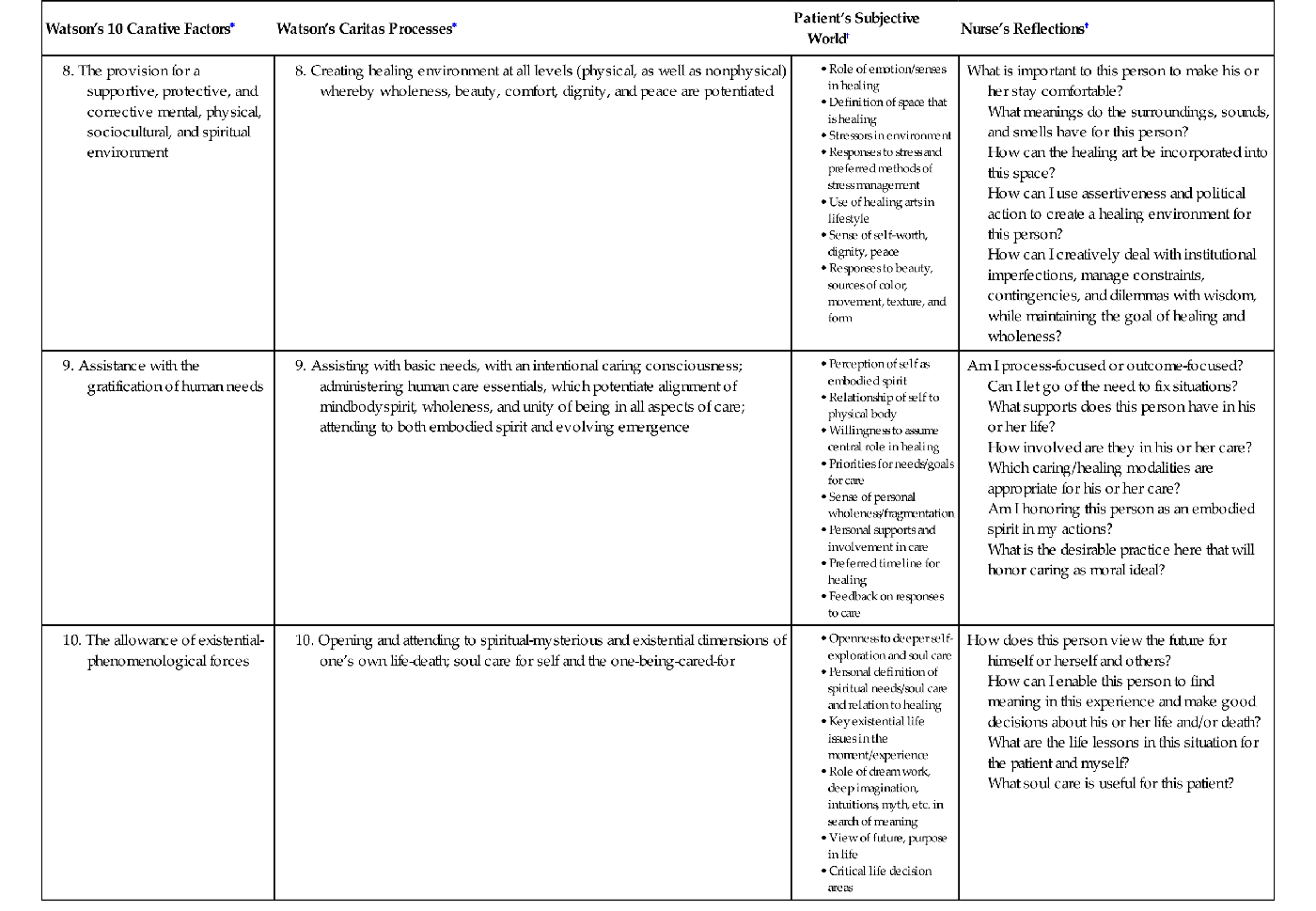

Watson’s (1979, 2008) scholarship of caring philosophy and science in nursing began as a textbook for an integrated nursing curriculum at the University of Colorado. Beginning with the question of the relationship between human caring and nursing, this initial work laid the foundation for what was to become The Theory of Human Caring: Retrospective and Prospective (Watson, 1997); Nursing: Human Science and Human Care (Watson, 1988a), Caring Science as Sacred Science (2005), Nursing: The Philosophy and Science of Caring (2008), and her latest book, Human Caring Science: A Theory of Nursing (2011). Watson defines caring as the ethical and moral ideal of nursing with interpersonal and humanistic qualities. It is a complex concept involving development of a range of knowledge, skills, and expertise that encompass holism, empathy, communication, clinical competence, technical proficiency, and interpersonal skills (Watson, Jackson, & Borbasi, 2005). She defines caring science as “an evolving philosophical-ethical-epistemic field of study, grounded in the discipline of nursing and informed by related fields” (Watson, 2008, p. 18). Watson desired to bring meaning and focus to nursing as an emerging discipline and a distinct health profession with unique values, knowledge, practices, ethics, and mission (Watson et al., 2005). Her early writing (1979) identified 10 carative factors that served as the foundation and framework for the science and practice of nursing (Table 6-1). The original carative factors grounded in philosophy, science, art, and caring evolved into the theory of human caring (Watson, 1985, 1988a, 1995, 1997). In later works, Watson (1999, 2005, 2008, 2011) revised the original carative factors with the emerging concepts of “clinical caritas” and “carative processes.” These processes, also included in Table 6-1, emphasize the sacred and spiritual dimension of caring. “Caritas” means to cherish, appreciate, and give special attention (Watson, 1999, 2005) and is related to “carative,” a deeper and expanded dimension of nursing that joins caring with love. Caritas is differentiated from “amore” that “tends to be a love in which self-interest is involved” (Watson, 2008, p. 253).

TABLE 6-1

| Watson’s 10 Carative Factors∗ | Watson’s Caritas Processes∗ | Patient’s Subjective World† | Nurse’s Reflections† |

| Who is this person? Am I open to participate in his or her personal story? How am I being called to care? How should I be in this situation? | |||

| What does this relationship mean to this patient? What health event brings this person to this health facility? What information do I need to nurse this person? Can I imagine what this experience is like? Can I encourage this person to find faith/hope? | |||

| How am I attending to this person’s spiritual needs and soul care? Does the experience of others nurture my compassionate self? Can I find new ways of caring? | |||

| How can I enter this person’s private space? Can I establish a caring dialogue to help this person find meaning in this experience? What specific forms of caring will best acknowledge, affirm, and sustain this person? What strategies can I use to help this person translate his or her concerns to me and use them as goals for his or her recovery and self-healing? | |||

| How can I enable this person to express his or her concerns? How must this person be feeling? How does this person show his or her pain? What are the mores about pain in his or her culture? What are the subtle patterns that surface in this person’s story? Can I use this to help him or her understand the deep meanings of his or her health event/moment? Am I meeting my obligation to reveal my understandings to the one-being-cared-for with a healing intent? | |||

| What is the uniqueness of this person and this situation? How has this event affected his or her usual life patterns and roles? How can I contextualize the theory of care for this person and situation? How does this situation compare with my previous experience? What are the significant issues to attend to? How can I help this person? Which healing arts are appropriate? | |||

• Definition of health, healing, wholeness • Understanding of experiences, self-care needs, and limitations • Awareness of personal resources, strengths for healing • Identification of habitual ways of responding • Sense of freedom and commitment to action • Past experiences with learning and health • Openness to self-discovery, participative learning, accessing external resources | Is this person able to understand what he or she is experiencing? Is he or she aware of his or her choices and their consequences? How does this person view the future? How can this person’s concerns be translated into goals for recovery? What are his or her preferred ways of knowing? How can I share knowledge in a way that can assist with self-care and healing? | ||

| What is important to this person to make his or her stay comfortable? What meanings do the surroundings, sounds, and smells have for this person? How can the healing art be incorporated into this space? How can I use assertiveness and political action to create a healing environment for this person? How can I creatively deal with institutional imperfections, manage constraints, contingencies, and dilemmas with wisdom, while maintaining the goal of healing and wholeness? | |||

| Am I process-focused or outcome-focused? Can I let go of the need to fix situations? What supports does this person have in his or her life? How involved are they in his or her care? Which caring/healing modalities are appropriate for his or her care? Am I honoring this person as an embodied spirit in my actions? What is the desirable practice here that will honor caring as moral ideal? | |||

| How does this person view the future for himself or herself and others? How can I enable this person to find meaning in this experience and make good decisions about his or her life and/or death? What are the life lessons in this situation for the patient and myself? What soul care is useful for this patient? |

∗From Watson, J. (1979). Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring. Boston: Little, Brown. (Reprinted 1985, Boulder: University Press of Colorado); Watson, J. (2008). Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

†From Watson, J. (1998). A meta-reflection on reflective practice and caring theory. In C. Johns & D. Fleshwater (Eds.), Transforming nursing through reflective practice (pp. 214-220). London: Blackwell Science; Watson, J. (1999). Postmodern nursing and beyond. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Saunders.

Watson describes the core of nursing as those aspects of nursing that potentiate therapeutic healing processes and relationships, transcending time and “trim” of nursing, such as procedures, tasks, treatments, and technology. Watson calls caring “the ethical principle or standard by which curing interventions are measured” (1988b, p. 2). Within this caring ontology, technical interventions commonly aimed at cure are reframed as sacred acts conducted with a caring consciousness and completed in a way that honors the person as an embodied spirit. Watson differentiates “care” from “cure” but describes them as compatible and complementary aspects of nursing (Watson et al., 2005).

Watson (2005, 2008) draws on the works of other theorists and proposes linkages among Caring Theory (CT), the Science of Unitary Human Beings (SUHB) (Rogers, 1970, 1992, 1994; Watson & Smith, 2002), and Health as Expanding Consciousness (Newman, 1994), integrating Rogers’ principle of resonancy with caring consciousness. Caring science is noted as an interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary field of study (Watson, 2002a,b, 2005, 2008, 2011).

Although Watson’s work does not deny the importance of empirical factors and the physical world of nursing practice, she embraces concepts of mind, consciousness, soul, the sacred, the ancient, the contemporary Yin emergence, holism, energy fields, waves, energy exchange, quantum, holography, transcendence, time and space, healing artistry, evolution, and the transpersonal. Watson’s language also includes more elemental grounds of being: beauty, truth, goodness, harmony, openings, possibility, beyond, deep understanding, oneness, coming together, nurturance, honoring, authenticity, wide awakeness, human sensitivity, suffering, pain, hope, joy, spiritual, the divine, grace, the mystical, dream work, passion, poetry, metaphor, nature, I-thou, awe, dignity, reverence, ritual, light, the sacred feminine, wonder, compassion, love, blessings, peace. It is here that practicing nurses find the CT’s truest resonance and hope. Despite some challenges Watson is an eternal optimist (Watson, 1999, 2005) who writes about the personal as well as the sacred.

Watson’s book, Caring Science as Sacred Science (2005), tells how her professional and personal journeys converge as she describes her healing after traumatic events in her life. Watson (2005, 2008) refers to Nightingale’s work and spiritual “calling” to practice, a pivotal experience that gave strength to her convictionthat she was destined for an unconventional life (Watson, 1999, 2005). Watson (2002b) writes:

For Nightingale, nursing was a spiritual practice, and spirituality was considered intrinsic to human nature and a potent resource for healing; she was clear about nursing being a calling; she articulated nursing’s healing role, working in harmony with nature. In this heritage, nursing and its focus on caring and healing in harmony with nature and environmental conditions, was a form of values-guided, artful practice, attending to basic human essentials, grace and beauty (p. 4).

Nightingale (cited in Watson, 2008, p. 252) stated that health “is not only to be well, but to be able to use every power we have to use.” Watson’s writings encourage similar exploration with questions such as the following:

Watson views nursing as “both a human science and an art.” Her description of her science places her work firmly in human science by disclosing the symbolic, conceptual, and linguistic world while practicing within a material, concrete, sensual world (Watson, 1988a; Wilber, 1999). She champions a broad definition of nursing science with its own concepts, relationships, and methodology, a science with vistas and opportunities to understand nursing from a view of caring human experience (Watson, 1990). According to Watson (1989):

this science with a view…leans toward employing qualitative theories and research methods, such as existential-phenomenology, literary introspection, case studies, philosophical-historical work, hermeneutics, art criticism, and other approaches that allow a close and systematic observation of one’s own experience and that seek to disclose and elucidate the lived world of health-illness-healing experience and the phenomena of human caring (p. 221).

This interpretation of science does not negate the significant contributions of objective medical and nursing science but does include subjective experience and values, meaning, quality, and soul-to-human phenomena allowing an integral view of the whole. In Postmodern Nursing and Beyond (1999), Watson clearly proposed four aspects of caring: (1) as moral ideal, (2) as intentionality, (3) as ontological competencies, and (4) as healing art and healing space in the theory of transpersonal caring-healing.

Overview of Watson’s Philosophy of Human Caring

Watson describes her work as a framework, theory, model, worldview, or a paradigm that is transdisciplinary. She expands the original 10 carative factors to a science, philosophy, and ethic of human caring useful for all health professionals and healing practitioners, particularly those practicing mind-body medicine (Watson, 2005, 2008). Watson’s paradigm of caring in the human health experience is recognizedwithin the discipline (Newman, Sime, & Corcoran-Perry, 1991; Watson, 2005, 2008, 2011). Educators will find Creating a Caring Science Curriculum (Hills & Watson, 2011) useful, and Measuring Caring: International Research on Caritas as Healing (Nelson & Watson, 2011) is particularly useful to those researching caritas as healing. Watson’s (2011) latest update on nursing practice with this theoretical approach is Human Caring Science: A Theory of Nursing (Watson, 2011). Although there are various caring theories, Watson maintains that caring is central to the professional discipline of nursing (Newman et al., 1991; Watson, 1990; Watson & Smith, 2002); and that her book Nursing: The Philosophy and Science of Caring “could equally be titled Caring: The Philosophy and Science of Nursing” (Watson, 2008, p. 15). The nursing metaparadigm concepts (human being, health, nursing, and environment) from the perspective of Watson’s theory follow.

Human Beings (Personhood)

Person is viewed holistically wherein the body, mind, and soul are interrelated, each part a reflection of the whole, yet the whole is greater than and different from the sum of parts (Watson, 1979, 1989). The person is a living, growing gestalt that possesses three spheres of being—body, mind, and soul—influenced by the concept of self. The mind and emotions are the starting point and the access to the subjective world. The self, the seat of identity, is the subjective center that lives within the whole of body, thoughts, sensations, desires, memories, and life history. She gives honor to deep meanings and feelings about life, living, the natural inner processes, personal autonomy, and freedom to make choices shaped by subjective intent (Watson, 1985, 1999). Watson says, “The person is neither simply an organism, nor simply spiritual. A person is embodied in experience in nature and in the physical world and a person can also transcend the physical world by controlling it, subduing it, changing it, or living in harmony with it” (1989, p. 225).

Watson’s notions of personhood and life are based on the concept of human beings as embodied spirit. Within this transpersonal framework, the body is a living spirit that manifests one’s being-in-the-world and one’s way of standing and reflects how one holds oneself with respect to one’s relation to self and one’s consciousness or unconsciousness (Watson, 1999). This view holds respect and awe for the concept of the human soul (also called spirit, geist, or higher sense of self) transcending the physical, mental, and emotional existence of person. The soul and spirit are those aspects of consciousness that are not confined by space and time or linearity. By emphasizing the spiritual dimension of life, Watson speculates on the human capacity to co-exist with past, present, and future in the moment. She respects the dignity, reverence, chaos, mystery, and wonder of life because of the continuous yet unknown journey the soul takes through the infinite and eternal. Watson (1999) views the soul as “the essence of the person, which possesses a greater sense of self-awareness, a higher (ascent) degree of consciousness, an inner strength, and a power that can expand human capacities and allow a person to transcend his or her usual self” (p. 224). The soul fully participates in healing. As nurses and future nurses, we continue to explore the spiritual, nonphysical, inner, and extrasensory (beyond the five senses) realms to learn of the dynamic and creative energy currents of the soul’s existence and to learn of the inner healing journey toward wholeness (Watson, 1999).

“Human life is defined as being-in-the-world, which is continuous in time and space” (Watson, 1989, p. 224). The locus of human existence is experience, broadly defined as sensorimotor experience, mental/emotional experience, and spiritual experience. Experience is translated through multiple layers of awareness. Consciousness has the capacity to construct and create. The world as experienced is not merely reflected and interpreted by consciousness; it is co-created. Collective and individual worldviews are dynamic and co-created.

Nursing (Transpersonal Caring-Healing)

Watson (1999) describes nursing as transpersonal that “conveys a human-to-human connection in which both persons are influenced through the relationship and being-together in the moment. This human connection…has a spiritual dimension…that can tap into healing” (p. 290). She continues, “transpersonal includes the unique individuality of each human, while extending beyond ego-self” (p. 290). The goal of nursing in the caring-healing process is to help persons gain a higher degree of harmony within the mindbodyspirit, which generates self-knowledge, self-reverence, self-healing, and self-care processes allowing for diverse possibility. Watson suggests the greater the “degree of genuineness and sincerity” (Watson, 1985, p. 69) of the nurse within the context of the caring act, the greater the efficacy of caring. The nurse pursues this goal and testable proposition by integrating caritas processes and human care processes with intention, transpersonal caring, and relationship, responding to the subjective world of persons such that individuals find meaning in their existence by exploring the disharmony, suffering, and turmoil within the lived experience. This exploration promotes self-knowledge, self-control, self-love, choice based on subjective intent, and self-determination. Watson emphasizes the nursing act of helping persons while preserving the dignity and worth of the patient or client regardless of his or her situation (Watson, 1979, 1985, 1999, 2005, 2008, 2011).

Caring science allows nurses to approach the sacred in caring-healing work (Watson, 2005, 2008). In caring sciences, compassionate human service and caring are motivated by love. The general goal is biophysical-mental-spiritual evolution for self and others as well as discovery of inner power and self-control through caring. Shifting the focus from illness, diagnosis, and treatment to human caring, healing, and promoting spiritual health potentiates health, healing, and transcendence (Watson, 1999). Watson describes nurse as noun and verb. The noun nurse represents the discipline of nursing. The verb nurse is engaged in the caring-healing praxis, demonstrating ontological and epistemological competencies and redefining technological competencies as sacred acts manifest with an intentional caring-healing consciousness. She states, “Therefore, it is important to find ways to cultivate a consciousness of Caritas: loving-kindness and equanimity if one is to authentically practice within this paradigm” (Watson, 2008, p. 56). Equanimity means knowing one has a balanced spirit and ability to be in the present moment (2008). Healing, redefined, relates directly to the individual’s evolving personhood. Transpersonal caring-healing is a moral ideal and ontology. Informed moral passion and caring ontology are nursing’s substance (Watson, 1990). As the essence of nursing, “caring is the most central and unifying focus for nursing practice” (Watson, 1988a, p. 33). Caring, as a moral ideal, encourages the nurse to attempt to hold the conscious intentto preserve wholeness, to potentiate healing, and to preserve dignity, integrity, and life-generating processes (Watson, 1999).

In Watson’s theory, a single caring moment becomes a moment of possibility (Watson, 1989). She explains that:

Transpersonal describes an intersubjective, human-to-human relationship that encompasses two unique individuals, both the nurse and the patient, in a given moment. Simultaneously the relationship transcends the two subjectivities, connecting to other higher dimensions of being and a higher/deeper consciousness that accesses the universal field and planes of inner wisdom: the human spirit realm (p. 115).

Coming together in the moment provides an opportunity—an actual occasion—for human caring to occur. Human caring is actualized in the moment based on the actions and choices made by both the one-caring and the one-being-cared-for. The nurse and patient both determine the relationship and the use of that moment in time and space. In the moment, how the nurse chooses to be and to act will have significant effect on the opportunities of the moment and the eventual outcomes. The goal in the relationship is the protection, enhancement, and preservation of the dignity, humanity, wholeness, and inner harmony of the patient or client. This outcome for the patient is achieved through heightened self-knowledge, self-control, self-care, caring, and self-healing. The nurse influences these outcomes by intentional use of caring consciousness in the moment and by holding intentionality toward wholeness as a moral ideal. Caring-healing consciousness is an intentionality of love and wholeness that is a source and form of life energy, life spirit, and vital energy that can be communicated by the one-caring to the one-being-cared-for, which potentiates healing (Watson, 1999). She challenges educators to model transpersonal caring by encouraging self-affirmation and self-discovery in students, using teaching moments as “caring occasions” in a values-based moral curriculum (Bevis & Watson, 2000). Watson (2008) describes “Caritas educators of nurses and health care professionals…face a double challenge in establishing, promoting, and maintaining the human-to-human dialogue and caring relationships as the epicenter of the curriculum and teaching” (p. 261). Yet competencies of being, such as these, are essential for teaching transpersonal caring-healing.

The healing arts activate specific responses to promote wellness and centering, act as modes of expression and meditation, comment on healing and illness experiences, and provide psychoarchitecture for healing spaces. Watson integrates and embraces visual art and poetry to illustrate and enhance her concepts. Examples are her use of Sylvia Plath’s poem “Tulips” to illustrate the importance of not separating science and human values and use of a painting to the necessity for adequate ventilation for mine workers in the workplace.

Advanced caring-healing arts, or modalities, are integral to transpersonal practice. These modalities are also extensions of the carative factors of Watson’s earlier work (1985) and the art of transpersonal caring that included “movement, touch, sounds, words, color, and forms” (pp. 66-68). These advanced caring-healing modalities include the intentional conscious use of imagery and auditory, visual, olfactory, tactile, gustatory, mental-cognitive, kinesthetic, and caring consciousness, which includes psychological and therapeutic presence modalities (Watson, 1999, 2008).By exploring the integration of such therapies as music, visualization, breath work, aromatherapy, therapeutic touch, massage, caring touch, reflexology, dream work, humor, play, journaling, poetry, art making, meditation, transpersonal teaching, dance, yoga, movement, authentic presencing, and centering into caring practice as options for patient healing, the nurse acknowledges the emerging consciousness paradigm. Within this transpersonal philosophy and theory, different caring-healing modalities may be operating as sources of the patient’s healing at different levels across the spectrum of consciousness. The advanced healing arts Watson outlines as the carative factors/carative processes (see Table 6-1) does not preclude other practices including emotional, expressive, and relational work; comfort measures; and teaching-learning (Watson, 1979, 1985, 1988a, 2008, 2010). According to Watson (1999), “To be implemented into care, they require of the nurse’s intention, caring values, knowledge, a will, a relationship, actions, and commitment” (p. 227).

Intentionality is the projection of awareness or consciousness with some purpose and efficacy toward some object or outcome. The conscious use of intention mobilizes internal and external resources to meet the intended purpose (Watson, 1999). Watson (1999) has said, “If our conscious intentionality is to hold thoughts that are caring, open, loving, kind, and receptive, in contrast to an intentionality to control, manipulate and have power over, the consequences will be significant for our actions” (p. 121).

Health

Health is redefined in this philosophy as unity and harmony within the body, mind, and soul and harmony between self and others and between self and nature and openness to increased possibility. Watson (1989, 1999, 2008, 2011) defined health as a subjective experience and a process of adapting, coping, and growing throughout life that is associated with the degree of congruence between self as perceived and self as experienced. Thus nursing focuses on the individual’s view of health or illness. Health focuses on physical, social, esthetic, and moral realms and is viewed as consciousness and a human-environmental energy field. Health reflects a person’s basic striving to actualize and develop the spiritual essence of self (Watson, 1988a). It is a search to connect with deeper meanings and truths and “embrace the near and far in the instant and to seize the tangible, manifestly real, and the divine” (Watson, 1999, p. 80). Watson views health and illness functioning simultaneously as a way to stabilize and balance one’s life (Watson, 1979). Illness is subjective turmoil or disharmony within a person’s inner self or soul at some level or disharmony within the spheres of mind, body, and soul. Illness connotes a felt incongruence within the person such as incongruence between the self as perceived and the self as experienced (Watson, 1985, 1988a), yet it is also an “invitation to understand, to gain new meaning for one’s life pattern, to see health and illness as evolving consciousness and opportunist for healing” (Watson, 2008, p. 228). Illness may lead to disease but not on a continuum. Rather, she suggests that health, illness, and disease may exist simultaneously (Watson, 2008).

Within the transpersonal caring relationship and the caring moment, there is healing potential. Nurses work with people during times of despair, vulnerability, and death. Watson and Smith (2002) acknowledge that caring knowledge transcends all health disciplines but point out that the “nursing disciplinary focus on the relationship of caring to health and healing differentiates it from other disciplines…” (p. 456).

Environment (Healing Space)

In the 10 carative factors and in clinical caritas, Watson (1999, 2008) addresses the nurse’s role in the environment based on Nightingale’s tradition of the significance of the environment for healing: “attending to supportive, protective, and/or corrective mental, physical, societal, and spiritual environments” (Watson, 1979, p. 10) and recently as “creating a healing environment at all levels” (Watson, 2008, p. 129). Watson (1999, 2005, 2008) has broadened her focus from the immediate physical environment to a nonphysical energetic environment, vibrational field integral with the person (Quinn, 1992; Watson, 1999, 2005, 2008, 2011). The nurse becomes the environment in which “sacred space” is created. She describes how the “nurse is not only in the environment, able to make significant changes in the ways of being/doing; knowing in the physical environment, but that the nurse IS the environment” (Watson, 2008, p. 26). This environment promotes the intentional healing role of architecture (or surroundings) alongside conscious, intentional, caring, healing modalities. Conscious attention to healing spaces shifts the health care facility from being simply a place for bodies to be treated to a place in which there is conscious promotion of mindbodyspirit wholeness, attention to the relationship between stress and illness, recognition of hospital stress factors, and acknowledgment of the key role that emotions and the senses play in healing. Through the intentional introduction of quiet, art, favorite music and colors, pleasant smells, beautiful views of nature, mythology, and the patient’s favorite rituals and symbols of expressions of humanity and culture, healing spaces can assist in transcending illness, pain, and suffering.

Watson describes a caring/love that radiates in concentric circles from self, to others, the community and planet, and the universe, “nurses with informed Caritas Consciousness could literally transform entire systems, contributing to worldwide changes through their own practices of being, thus ‘seeing’ and doing things differently…” (Watson, 2008, p. 59). Yet, she recognizes how environmental challenges to concepts of caring—including a diminishing workforce, admission of more acutely ill patients with complex needs, cultural differences, economic factors, as well as organizational, social, and health care policies—influence the amount and quality of time a nurse can spend with clients/patients (Watson, 1999, 2005, 2008, 2011).

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice with Watson’s Philosophy and Theory

Engaging in Watson’s philosophy and caring theory involves subjectivity and reflection. She suggests that you:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree