CHAPTER 2

Vascular Nursing Research and Evidence-Based Practice

Patricia Matula

Kathleen Rich

First Edition Author: Patricia Matula

OBJECTIVES

1. Define the research process.

2. Identify key areas of nursing research related to vascular nursing.

3. Differentiate between quantitative and qualitative designs.

4. Discuss the relationship between research and evidence-based practice.

5. Describe the process for evidence-based practice.

Introduction

The spirit of inquiry and dedication to life-long learning is critical to overcoming the barriers to research and disseminating evidence into vascular nursing practice. The statistic that “it takes an average of 17 years to move research into practice” persists in many healthcare institutions. Point-of-care clinicians need to have the tools to use research evidence in their practices to improve patient outcomes (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2010).

I. Vascular Research

I. Vascular Research

A. Definition: A scientific process that uses a systematic inquiry to answer questions or solve problems related to vascular nursing. In addition, it validates and refines existing knowledge that directly and indirectly influences clinical vascular nursing practice.

B. Purpose of Vascular Research

1. Generate new scientific knowledge and expand previously generated knowledge for the practice of vascular nursing.

2. Create research-based and evidence-based nursing care that ensures quality and cost-effective outcomes (Sigma Theta Tau Nursing Practice and Education Consortium, 2005).

3. Identify the experience of the patient and family in all types and stages of vascular disease.

4. Identify the impact of vascular disease on patients, family, and the healthcare economy.

5. Identify attitudes and characteristics of nurses caring for the vascular patient.

6. Demonstrate the efficacy of nursing in the changing healthcare arena.

7. Define the specialty of vascular nursing.

8. Identify research priorities in vascular nursing.

C. Importance of Vascular Research to Practice

1. Nurse related

a. Defining the specialty and the specific body of knowledge for nursing is essential.

b. Knowledge related to patient response allows congruence between nurse and patient information.

c. The use and practice of research is one of the expectations of nursing, by both the Society for Vascular Nursing and the American Nurses Association (SVN and ANA standards of practice).

d. The use of research provides a current and legally defensible practice of the specialty.

e. Knowledge of current professional research is essential for professional pride and growth.

f. Dissemination of research is a professional responsibility.

2. Patient/practice related

a. Create a research-supported, evidence-based infrastructure that ensures current nursing practice is consistent with best available knowledge.

b. Quantifying outcomes in relation to interventions is necessary for appropriate utilization of research.

c. Research provides a patient worldview for nurses (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2011).

3. Cost related

a. Research-supported, evidenced-based vascular nursing practice may improve nursing efficiency resulting in institutional cost savings.

b. Delivering research-supported vascular nursing practice may lessen avoidable hospital admissions and readmissions, thus reducing payer and provider costs.

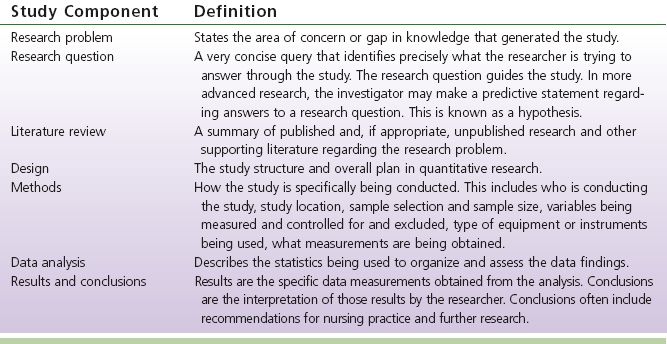

D. Outline of a Study (see Table 2-1)

E. Study Designs: Methods used to examine the relationships between and among variables measured.

1. Quantitative (deductive) studies: used to explain and predict phenomena, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, create evidence for cause and effect, test theory or instruments, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

a. An independent variable is the stimulus or activity manipulated to create an effect on the dependent variable. Control is critical to quantitative designs to ensure consistency of methods and minimize the role of chance.

b. A dependent variable is the behavior, response, or outcome the researcher wants to explain.

c. Sampling is the process of selecting a portion of the population to participate in the study. Researchers conduct a power analysis to determine what the sample size needs to be to minimize finding based on chance.

d. Validity is the extent to which the variable or intervention measures what it is supposed to measure. Internal validity refers to integrity of the design. External validity refers to the appropriateness by which results can be applied to nonstudy patients or populations. Note: Type I error: The researcher concludes that a relationship exists when there is none (reject the null hypothesis). Type II error: The researcher concludes that no relationship exists when in fact it does (accept the null hypothesis).

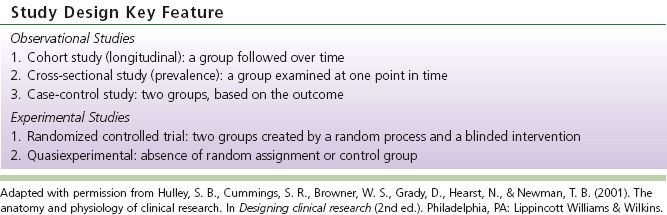

e. Common examples of designs used in quantitative research studies are described in Table 2-2.

TABLE 2-1 Outline of a Study

TABLE 2-2 Study Designs

2. Qualitative inductive studies: use an interactive, systematic, subjective approach to describe life experiences and give them meaning (Burns & Grove, 2011).

a. Methods allow the researcher to gain insight by discovering meaning through a purposeful sample (participants are selected because they have common characteristics).

b. Data are collected in words as opposed to numbers.

c. Methods explore the richness and complexity of the phenomena. If the research study is not a pilot, then conducting a power analysis is appropriate. A power analysis allows the researcher to find a statistically significant difference when the null hypothesis is in fact false. A null hypothesis is a hypothesis which the researcher tries to disprove, reject, or invalidate. The power of a study is determined by three factors: the sample size, the alpha level, and the effect size.

d. Trustworthiness: a method of appraising qualitative research according to Lincoln and Guba (1985).

1) Credibility (parallels internal validity): documentation of processes, period of engagement, data appropriateness (purposeful sample), adequacy of database (saturation), use of multiple data sources (saturation), validation of data and findings with participants.

2) Transferability (external validity): extent to which research findings can be applied to experiences of those in similar situations.

3) Dependability (reliability): requires meticulous documentation of the research process.

4) Confirmability (objectivity): extent to which the findings and interpretation are grounded in data.

e. Common approaches to qualitative research include the following:

1) Phenomenological research describes the experience as lived by the participant. Data are generated through observation, interview, videotape, and/or writings of the participants.

2) Grounded theory is rooted in sociology and approaches data to develop theories about phenomena being studied. The theory then explains the social process.

3) Ethnography is rooted in anthropology and studies the culture of people. The outcome is a detailed description of phenomena as observed through immersion in the culture.

4) Historical research or historiography studies past events in a systematic method. The result is a retelling of the events and their meaning.

5) Content analysis uses numbers to represent frequency, order, or intensity of words or phrases. Theoretical categories are then identified.

F. Epidemiology studies the distribution and determinants of disease frequency in populations. It scrutinizes illness patterns within a population and then attempts to ascertain why some individuals develop a disease whereas others do not (Greenberg, Daniels, Flanders, Eley, & Boring, 2005).

1. Determine what factors might be associated with disease (risk factors).

2. The higher the correlation, the more certain the association.

3. Two basic types of studies retrospective, whether the events have already happened or prospective, whether the events may happen in the future.

4. The Framingham Heart Study is the largest database on risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

G. Measurement is the process of assigning numbers to objects, events, or situations according to a rule. Levels of measurement:

1. Nominal: lowest level of measurement. Data can be organized into categories but cannot be manipulated.

2. Ordinal scale: data can be ranked but the intervals are not necessarily equal. The number is significant in terms of position.

3. Interval scale: order and equal distance between intervals. Mutually exclusive categories, such as temperature.

4. Ratio scale: highest level of measurement.

H. Protection of Human Subjects

1. All nursing research must be approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB). An Investigational Review Board is a multidisciplinary group (physicians, nurses, chaplains, administration, legal, community persons) that is responsible for assuring that all research projects conducted within the facility that require human or animal subjects are in accordance with the appropriate federal regulations.

2. Informed consent: The knowing consent of an individual or legally authorized representative to decide whether or not to participate in a research study without undue inducement or any elements of fraud, force, deceit, duress, constraint, or coercion.

3. Elements of informed consent

a. Decisional capacity: The participant has the ability to understand and make decisions.

b. Disclosure: The relevant risks, benefits, alternative treatments, and uncertainties have been discussed with the participant.

c. Understanding: The participants understand at least what the researcher believes they need to understand to authorize the study.

d. Voluntary: The participant agrees to the interventions without undue duress.

e. Consent: A written form documenting the acceptance of the intervention has been completed. The participant understands consent can be withdrawn at any time.

II. Evidence-Based Practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011)

II. Evidence-Based Practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011)

A. Definition: Evidence-based practice (EBP) is a problem-solving approach to clinical practice that integrates the following—a systematic search for and critical appraisal of the most relevant evidence to answer a burning clinical question; one’s own expertise; and patient preferences and values.

B. Steps to Evidence-Based Practice

1. Ask the burning clinical question.

2. Collect the most relevant and best evidence and rank using a hierarchal approach (Long, 2009).

a. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses (strongest).

b. Randomized controlled trials.

c. Controlled trials without randomization.

d. Cohort or case-controlled studies.

e. Descriptive or qualitative studies.

f. Expert opinions or case reports (least strong).

3. Critically appraise and grade the evidence using an accepted grading scale.

4. Integrate all evidence with one’s clinical expertise, patient preferences, and values in making a practice decision or change.

5. Evaluate the practice decision or change.

C. Ask the Burning Question using a PICO Format, then Modify the Below Subletters as Follows:

1. Patient population or Problem (describes the group of patients or problem identified).

2. Intervention of interest (cause, prevention, treatment strategy).

3. Comparison of interest (if appropriate, what is the main alternative).

4. Outcome (what could this intervention really affect).

D. Collect the Most Relevant and Best Evidence.

1. Systematic reviews or meta-analyses (COCHRANE, Joanna Briggs Institute).

2. Clinical practice guidelines (National Guideline Clearinghouse).

3. Randomized controlled trials (MEDLINE or Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL]).

4. All other types of studies: single descriptive or qualitative studies.

5. Expert opinion or reports of expert committees.

E. Critically Appraise the Evidence.

1. What was the sample size?

2. What were the results of the study?

3. Are the results valid?

4. Will the results help me in caring for my patients?

F. Integrate the Evidence from the Literature with the Following:

1. Healthcare provider’s expertise.

2. Clinical assessment of the patient and available healthcare resources.

G. Evaluate Effectiveness.

1. How did the treatment work?

2. How effective was the clinical decision with a particular patient or practice pattern?

III. Use of Evidence-Based Practice Nursing Models

III. Use of Evidence-Based Practice Nursing Models

A. EBP Nursing Models Assist the Nurse into Moving Evidence into Practice.

B. EBP Nursing Models can Organize the Method Strategies, Improve use of Resources, Maximize Nursing Time, and allow for a More Complete Implementation (Gawlinski & Rutledge, 2008).

C. Each Model Follows a Specific Algorithm or Series of Steps in this Process.

D. There are Several Different Models Available: Selection is Dependent on the One that Best Meets the Needs of the Individual Institution.

E. Examples of Commonly Utilized EBP Nursing Models include Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality of Care, Stetler’s Model, and John Hopkins Nursing Model.

Research Terms

Absolute risk: The observed or calculated probability of an event in the population under study.

Absolute risk difference: The difference in the risk for disease or death between an exposed population and an unexposed population.

Absolute risk reduction (ARR): The difference in the absolute risk (rates of adverse events) between study and control populations.

Bias (Syn: systematic error): Deviation of results or inferences from the truth, or processes leading to such deviation.

Blind(ed) study (Syn: masked study): A study in which observer(s) and/or subjects are kept ignorant of the group to which the subjects are assigned, as in an experimental study, or of the population from which the subjects come, as in a nonexperimental or observational study. When both observer and subjects are kept ignorant, the study is termed a double-blind study. When the statistical analysis is also done in ignorance of the group to which subjects belong, the study is sometimes described as triple blind. The purpose of “blinding” is to eliminate sources of bias.

Case series: Report of a number of cases of a particular disease.

Case-control study: Retrospective comparison of exposures of persons with disease (cases) with those of persons without the disease (controls) (see Retrospective study).

Causality: The effect of a treatment or intervention on an outcome. Three conditions necessary to establish causality are (a) a strong correlation between proposed cause and effect; (b) the proposed cause must precede the effect in time; and (c) the proposed cause must be present every time the effect occurs.

Cohort study: Follow-up of exposed and nonexposed defined groups, with a comparison of disease rates during the time covered.

Comparison group: Any group to which the index group is compared; usually, synonymous with control group.

Comorbidity: Coexistence of a disease or diseases in a study participant in addition to the index condition that is the subject of study.

Confidence interval (CI): The range of numerical values in which we can be confident (to a computed probability, such as 90% or 95%) that the population value being estimated will be found. Confidence intervals indicate the strength of evidence; when confidence intervals are wide, they indicate less precise estimates of effect. The larger the trial’s sample size, the larger the number of outcome events and the greater the confidence that the true relative risk reduction is close to the value stated. Thus, the confidence intervals narrow, and “precision” is increased. In a “positive finding” study, the lower boundary of the confidence interval, or lower confidence limit, should still remain important or clinically significant if the results are to be accepted. In a “negative finding” study, the upper boundary of the confidence interval should not be clinically significant if you are to confidently accept this result.

Effectiveness: A measure of the benefit resulting from an intervention for a given health problem under usual conditions of clinical care for a particular group; this form of evaluation considers the efficacy of an intervention and its acceptance by those to whom it is offered, answering the question, “Does the practice do more good than harm to people to whom it is offered?” (see Intention-to-treat analysis).

Efficacy: A measure of the benefit resulting from an intervention for a given health problem under the ideal conditions of an investigation; it answers the question, “Does the practice do more good than harm to people who fully comply with the recommendations?”

Exclusion criteria: Conditions that preclude entrance of candidates into an investigation, even if they meet the inclusion criteria.

Experimental event rate (EER): The percentage of intervention/exposed group who experienced the outcome in question.

Follow-up: Observation over a period of time of an individual, group, or initially defined population whose relevant characteristics have been assessed to observe changes in health status or health-related variables.

Gold standard: A method, procedure, or measurement that is widely accepted as being the best available.

Hypothesis: A statement of predicted relationships between variables in a study.

Incidence: The number of new cases of illness commencing or of persons falling ill during a specified time period in a given population (see also Prevalence).

Intention-to-treat analysis: A method for data analysis in a randomized clinical trial in which individual outcomes are analyzed according to the group to which they have been randomized, even if they never received the treatment they were assigned. By simulating practical experience, it provides a better measure of effectiveness (versus efficacy).

Interviewer bias: Systematic error caused by the interviewer’s subconscious or conscious gathering of selective data.

Lead-time bias: If prognosis study patients are not all enrolled at similar, well-defined points in the course of their disease, differences in outcome over time may merely reflect differences in duration of illness.

Likelihood ratio: Ratio of the probability that a given diagnostic test result will be expected for a patient with the target disorder rather than for a patient without the disorder.

Number needed to treat (NNT): The number of patients who must be exposed to an intervention before the clinical outcome of interest occurs, for example, the number of patients needed to treat to prevent one adverse outcome.

p value: The statistical test of the assumption that there is no difference between an experimental intervention and a control p value. When a test of difference is significant at the 0.05 levels (p is usually 0.05) the researcher may conclude that there is a 95% probability that the two groups are different and the difference is not caused by chance.

Predictive value: In screening and diagnostic tests, the probability that a person with a positive test is a true positive (i.e., has the disease), or that a person with a negative test truly does not have the disease. The predictive value of a screening test is determined by the sensitivity and specificity of the test and by the prevalence of the condition for which the test is used.

Prevalence: The proportion of persons with a particular disease within a given population at a given time.

Prospective study: Study design in which one or more groups (cohorts) of individuals who have not yet had the outcome event in question are monitored for the number of such events that occur over time.

Randomized controlled trial: Study design in which treatments, interventions, or enrollment into different study groups are assigned by random allocation rather than by conscious decisions of clinicians or patients. When the sample size is large enough, this study design avoids problems of bias and confounding variables by ensuring that known and unknown determinants of outcome are evenly distributed between treatment and control groups.

Relative risk (RR): The ratio of the probability of developing, in a specified period of time, an outcome among those receiving the treatment of interest or exposed to a risk factor compared with the probability of developing the outcome if the risk factor or intervention is not present.

Relative risk reduction (RRR): The extent to which a treatment reduces a risk in comparison with patients not receiving the treatment of interest.

Reproducibility (repeatability, reliability): The results of a test or measure are identical or closely similar each time it is conducted.

Retrospective study: Study design in which data for individuals who had an outcome event in question are collected and analyzed after the outcomes have occurred (see also Case–control study).

Risk factor: Patient characteristics or factors associated with an increased probability of developing a condition or disease in the first place. Compare with prognostic factors. Risk or prognostic factors do not necessarily imply a cause-and-effect relationship.

Selection bias: A bias in assignment or a confounding variable that arises from study design rather than by chance. These can occur when the study and control groups are chosen so that they differ from each other by one or more factors that may affect the outcome of the study.

Sensitivity (of a diagnostic test): The proportion of truly diseased persons, as measured by the gold standard.

Specificity (of a diagnostic test): The proportion of truly nondiseased persons, as measured by the gold standard, who are so identified by the diagnostic test under study.

Strength of inference: The likelihood that an observed difference between groups within a study represents a real difference rather than mere chance or the influence of confounding factors, based on p values and confidence intervals. Strength of inference is weakened by various forms of bias and by small sample sizes.

Variable: Anything that varies; any property that takes on different values.

REFERENCES

Burns, N., & Grove, S. (2011). Understanding nursing research: Building an evidence-based practice (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Gawlinski, A., & Rutledge, D. (2008). Selecting a model for evidence-based practice changes. Advanced Critical Care, 19(3), 291–300.

Greenberg, R. S., Daniels, S. R., Flanders, W. D., Eley, J. W., & Boring III, J. R. (2005). Chapter 1. Introduction to epidemiology. In R. S. Greenberg, S. R. Daniels, W. D. Flanders, J. W. Eley, & J. R. Boring III (Eds.), Medical epidemiology (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Retrieved from http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=545000, accessed December 8, 2011.

Hulley, S. B., Cummings, S. R., Browner, W. S., Grady, D., Hearst, N., & Newman, T. B. (2001). Designing clinical research (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. (2010). Redesigning the clinical effectiveness research paradigm: Innovation and practice based approaches workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Long, C. (2009). Weighing in on the evidence. In N. Schmidt & J. Brown (Eds.), Evidence-based practice for nurses (pp. 315–331). Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2011). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing. (2005). Position statement on evidence-based nursing. Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International. Retrieved from http://www.nursingsociety.org/aboutus/PositionPapers/Pages/EBN_positionpaper.aspx, accessed September 1, 2013.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Baas, L. (2010). Nursing review and resource manual: Cardiac vascular nursing (3rd ed.). Silver Spring, MD: ANCC’s Institute for Credentialing Innovation.

Buckingham, J., Fisher, B., & Saunders, D. (rev. 2008). Evidence-based medicine tool kit. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, originally published in JAMA. Retrieved from http://www.med.ualberta.ca/#

Polit, D., & Beck, C. (2010). Essentials of nursing research (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer-Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Titler, M. G., Kleiber, C., Rakel, B., Budreau, G., Everett, L., Steelman, V., . . . Goode, C. (2001). The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 13(4), 497–509.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>