CHAPTER 15

Vascular Access

Ellen Malone

First Edition Author: Jeanne Doyle

OBJECTIVES

1. Identify three indications for long-term vascular access.

2. Name three common anatomical locations to obtain vascular access.

3. Differentiate between catheter, autogenous, and synthetic graft access.

4. Identify three potential complications of long-term vascular access.

Introduction and Overview

Vascular access is a term used to describe techniques designed to provide readily obtainable and dependable long-term/chronic access to the venous system for treatment interventions, such as hemodialysis, or the delivery of chemotherapy or nutritional supplementation. In most cases, vascular access devices provide a simple and relatively painless means of drawing blood or administering treatment. The most common types of vascular access are surgically created fistulae between an artery and vein (AV fistulae), and implantable (tunneled or nontunneled) intravenous catheters or port devices. This chapter provides an overview of these approaches.

I. Vascular Access for Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease

I. Vascular Access for Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease

A. Incidence and Significance

1. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects as many as 26 million people in the United States (13% of the population).

2. The incidence is significantly increased in those older than age 65.

3. More than 480,000 people with kidney failure are receiving hemodialysis requiring permanent, ‘‘durable’’ long-term access.

4. In addition to surgically created fistulae, an estimated 2.75 million vascular access devices are placed per year.

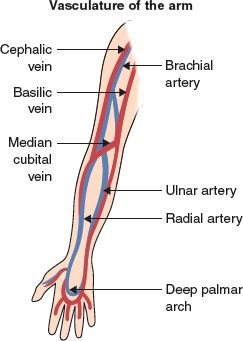

FIGURE 15.1 Vasculature of the arm.

II. Surgical Vascular Access for End-Stage Renal Disease

II. Surgical Vascular Access for End-Stage Renal Disease

(Note: Theoretically, an AV fistula can be surgically created anywhere in the body where an artery and vein of suitable size are available. Considerations such as patient comfort, accessibility, and ease of use for dialysis are important. Thus, the upper extremity is the most commonly used site.)

A. Anatomy (see Fig. 15-1)

1. Upper extremity arteries

a. Radial: located on lateral side of wrist, communicates with palmer arch

b. Ulnar: located on the medial side of wrist, also communicated with palmer arch

c. Brachial: located in antecubital area extending into the upper arm, joins proximally with (axillary artery which becomes the) subclavian artery

2. Upper extremity veins

a. Cephalic: located on lateral side of arm, courses from wrist to upper arm—joins the axillary vein in the upper arm, superficial in forearm so it is frequently visualized on physical examination

b. Basilic: located on medial side of arm, courses from wrist to upper arm—becomes the axillary vein at upper arm. It lies deeper in the tissue making it hard to visualize on physical examination

B. Assessment

1. Determination of dominant arm, (nondominant arm used if feasible)

2. Risk factors for poor vein quality in upper extremities include history of frequent or prolonged intravenous catheter including central lines and peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC), history of IV drug use, vein or arterial harvest, prior surgery or trauma to upper extremity, (primary prevention avoid trauma to or venipuncture of the arm vessels)

3. Palpation of radial, ulnar, and brachial arterial pulses

4. Allen test

a. Determines the ability of the ulnar artery to perfuse the hand via the palmer arch

b. Pressure is applied over the ulnar and the radial artery simultaneously resulting in pallor of the hand

c. Release of pressure over the ulnar artery will result in return of color due to rapid reperfusion of the hand if blood supply through the ulnar system is adequate and the palmar arch is intact

C. Diagnostic Testing

1. Blood pressure in both arms

2. Doppler systolic pressures of wrist arteries

3. Ultrasound vein mapping determines caliber of vessels and suitability for use

4. Doppler ultrasound arterial velocities to evaluate for stenosis

5. Venogram if there is a concern regarding vein quality or central venous stenosis

D. Surgical Management

1. Access to the vascular system for hemodialysis is most often achieved by surgical creation of an autogenous arteriovenous fistula

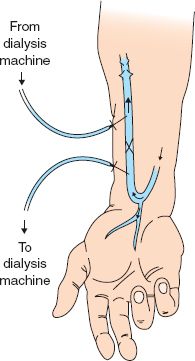

2. Fistulae should be created using the distal-most vessels in the upper extremity (e.g., the radial-cephalic fistula) to preserve more proximal vessels for future fistula formation (see Fig. 15-2)

3. More proximal surgical fistulae can be created using the brachial artery and cephalic or basilic veins in the upper arm

4. In the most extreme cases, vein can be harvested from the lower extremity for interposition fistula or a fistula can be created in the lower extremities

5. When suitable autogenous vein is not available, synthetic graft materials (i.e., PTFE, Dacron) may be used to create a ‘‘bridge’’ fistula between the artery and vein. Long-term patency rates with synthetic interposition grafts are inferior to autogenous fistulae

FIGURE 15.2 Brescia–Cimino (radial-cephalic) fistula.

E. Postsurgical Nursing Management

1. Acute postoperative care

a. Potential for acute thrombosis of fistula (often secondary to technical factors such as lack of adequate venous run-off)

1) Palpate/auscultate fistula for thrill/bruit

2) Report diminished or absence of thrill/bruit to surgeon

3) Maintain adequate blood pressure and fluid status

b. Potential for infection

1) Inspect surgical incision for signs/symptoms of infection or abscess

2) Report any fevers, increased pain, swelling or drainage

c. Potential for hemorrhage

1) Inspect surgical incision for development of hematoma or excessive bleeding

d. Potential for postoperative edema (anticipated because of changes in local hemodynamics and soft tissue injury)

1) Elevate arm with pillow or splint

2) Monitor for improvement of edema with time

3) Report persistent/worsening edema to surgeon (may be indicative of venous thrombosis or central venous stenosis)

2. Long-term care

a. Potential for late thrombosis (related to repeated trauma to outflow vein by needle punctures leading to fibrosis)

1) Palpate/auscultate for presence of thrill/bruit

2) Report absence to surgeon

3) Increase flow rate on hemodialysis

b. Potential for hemodynamic complications

1) Congestive heart failure related to increased venous return, resulting in compensatory increase in cardiac output and workload

2) ‘‘Steal syndrome’’ shunting of blood from the artery to the vein away from the palmar arch may result in pain in the hand on exertion

3) Pseudoaneurysm formation from repeated venipunctures that fail to seal

4) Distal venous hypertension/chronic edema (may worsen as fistula matures and valvular incompetence develops) characterized by edema, blue discoloration, and pigmentation of overlying skin

5) Aneurysm formation—may require surgical repair

6) Neuropathy/carpal tunnel syndrome

3. Preoperative patient teaching considerations

a. Psychological: effect of disease on perception of health and well-being

b. Psychosocial: impact on daily activities, time commitment for treatment, transportation to dialysis, and so forth

c. Physical: formation and care of fistula

d. Dialysis procedure

e. Nutritional counseling

4. Postoperative patient teaching considerations

a. Check for palpable thrill several times daily (report absence)

b. Report any signs/symptoms of infection

c. Avoid constrictive or circumferential dressing

d. No blood pressure cuffs or devices on operative arm

e. Avoid tight sleeves, wristwatch, or bracelets on operative arm

f. Avoid carrying heavy objects with operative arm

g. Encourage hand grip exercises several times a day post operation

III. Percutaneous Catheter Access to the Venous System

III. Percutaneous Catheter Access to the Venous System

A. Seldinger Technique: advancing a catheter over a guidewire, into a central vein

1. First reported for use in emergency fluid volume resuscitation and central venous pressure measurement. Led to the first use of central venous access for nutritional support (total parenteral nutrition)

2. The development of large-bore silicone catheters (e.g., Hickman, Broviac) has vastly improved the lives of patients requiring long-term parenteral therapy for nutrition, antibiotics for resistant infections, and chemotherapy

3. Further technical advancements have resulted in multiple-lumen catheters, allowing for infusion as well as outflow (e.g., blood sampling)

B. Central Venous Anatomy (see Fig. 15-3)

1. Subclavian vein

2. Internal jugular vein

3. Femoral vein (rarely used)

C. Insertion Technique

1. Neck and chest are prepped with cleansing solution and draped using sterile conditions

2. Patient is placed in slight Trendelenburg position

3. Local anesthesia is infused over the vessel being cannulated

4. Fluoroscopic guidance or ultrasound is optimal

Note: Catheters may be inserted via a surgical cut-down technique in patients with bleeding dyscrasias or in whom ‘‘blind’’ puncture might carry an increased risk.

D. Types of Catheters

1. Central venous tunneled catheters/ports (see Figs. 15-4 and 15-5)

a. First introduced by Broviac and colleagues in 1973

b. Composed of silicone with a Dacron polyester cuff that anchors the catheter in a subcutaneous tunnel

c. Newest catheters have an additional antimicrobial-impregnated cuff creating a physical barrier to bacteria

d. Available in single, double, or triple lumens

FIGURE 15.3 Central venous anatomy.