V

Vaginal, cervical, and vulvar infections

Definition

Infection and inflammation of the vagina, cervix, and vulva commonly occur when the natural defenses of the acid vaginal secretions (maintained by sufficient estrogen level) and the presence of Lactobacillus are disrupted. A woman’s resistance may also be decreased as a result of aging, poor nutrition, and the use of drugs (e.g., antibiotics, hormones) that alter the bacterial flora or mucosa.

Pathophysiology

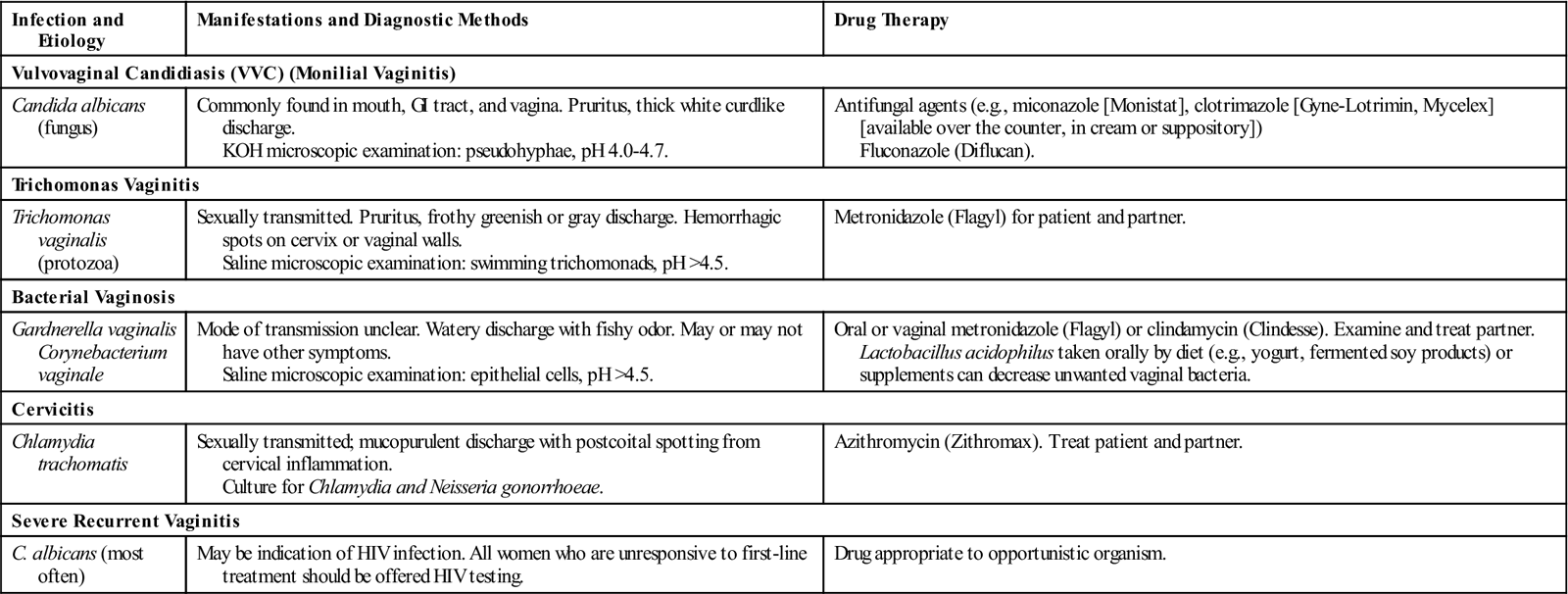

Organisms gain entrance to these areas through contaminated hands, clothing, and douche tips and during intercourse, surgery, and childbirth. Table 83 presents the etiology, clinical manifestations, diagnostic methods, and collaborative care of common infections of the lower genital tract.

■ Most lower genital tract infections are related to sexual intercourse. Vulvar infections, such as herpes and genital warts, can be sexually transmitted when no lesions are present (see Herpes, Genital, p. 309, and Warts, Genital, p. 672).

Table 83

Infections of the Lower Genital Tract

| Infection and Etiology | Manifestations and Diagnostic Methods | Drug Therapy |

| Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC) (Monilial Vaginitis) | ||

| Candida albicans (fungus) | Commonly found in mouth, GI tract, and vagina. Pruritus, thick white curdlike discharge. KOH microscopic examination: pseudohyphae, pH 4.0-4.7. | Antifungal agents (e.g., miconazole [Monistat], clotrimazole [Gyne-Lotrimin, Mycelex] [available over the counter, in cream or suppository]) Fluconazole (Diflucan). |

| Trichomonas Vaginitis | ||

| Trichomonas vaginalis (protozoa) | Sexually transmitted. Pruritus, frothy greenish or gray discharge. Hemorrhagic spots on cervix or vaginal walls. Saline microscopic examination: swimming trichomonads, pH >4.5. | Metronidazole (Flagyl) for patient and partner. |

| Bacterial Vaginosis | ||

| Gardnerella vaginalis Corynebacterium vaginale | Mode of transmission unclear. Watery discharge with fishy odor. May or may not have other symptoms. Saline microscopic examination: epithelial cells, pH >4.5. | Oral or vaginal metronidazole (Flagyl) or clindamycin (Clindesse). Examine and treat partner. Lactobacillus acidophilus taken orally by diet (e.g., yogurt, fermented soy products) or supplements can decrease unwanted vaginal bacteria. |

| Cervicitis | ||

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Sexually transmitted; mucopurulent discharge with postcoital spotting from cervical inflammation. Culture for Chlamydia and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. | Azithromycin (Zithromax). Treat patient and partner. |

| Severe Recurrent Vaginitis | ||

| C. albicans (most often) | May be indication of HIV infection. All women who are unresponsive to first-line treatment should be offered HIV testing. | Drug appropriate to opportunistic organism. |

Clinical manifestations

■ Abnormal vaginal discharge and reddened vulvar lesions are common.

■ The hallmark of bacterial vaginosis is the fishy odor of the discharge.

■ Women with cervicitis may notice spotting after intercourse.

Postmenopausal older women may develop gynecologic problems, such as lichen sclerosis, a chronic inflammatory condition associated with intense itching in the genital skin area. The lesions are white with a “tissue paper” appearance initially, although scratching produces changes in the appearance.

Diagnostic studies

■ History, physical examination, and sexual history.

■ Culture ulcerative lesions for herpes.

■ Vulvar dystrophies are examined by colposcope with biopsy specimens taken.

■ Microscopy and culture of vaginal discharge are done.

■ Bacterial vaginosis, VVC, and trichomoniasis are diagnosed by a wet mount.

Collaborative care

Antibiotics taken as directed will cure bacterial infections. Antifungal preparations (in oral or cream preparations) are indicated for VVC. Women with vaginal conditions or cervical infection should abstain from intercourse for at least 1 week. Douching should be avoided as it has been adversely linked to pelvic inflammatory disease, sexually transmitted infections, and ectopic pregnancy. Sexual partners must be evaluated and treated if the patient is diagnosed with trichomoniasis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, or HIV.

Treatment of vulvar dystrophies is symptomatic and involves controlling the itching and hence the scratching. Interrupting the “itch-scratch cycle” prevents further secondary damage to the skin.

Nursing management

Teach women about common genital conditions and how to reduce their risks. Recognize symptoms that indicate a problem and help women seek care in a timely manner.

When a woman is diagnosed with a genital condition, ensure that she fully understands the directions for treatment. Taking the full course of medication is especially important to decrease the chance of relapse. Because genitals are such a private area, use of graphs and models is especially helpful for patient teaching.

When a woman is using a vaginal medication such as an antifungal cream for the first time, show her the applicator and how to fill it. Also teach where and how the applicator should be inserted by using visual aids or models. Vaginal creams should be inserted before going to bed so that the medication will remain in the vagina for a long period of time. Women using vaginal creams or suppositories may wish to use panty liners during the day when the residual medication may drain out.

Valvular heart disease

Description

Valvular heart disease is defined according to the affected valve or valves (mitral, aortic, tricuspid, pulmonary) and the type of functional alteration: stenosis or regurgitation.

Valve disorders occur in children and adolescents mainly from congenital conditions. Aortic stenosis and mitral regurgitation are the common valve disorders in older adults. Other causes of valve disease in adults include disorders related to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and the use of some antiparkinsonian drugs (e.g., pergolide [Permax]).

Clinical manifestations of valvular heart disease are presented in Table 84.

Table 84

Manifestations of Valvular Heart Disease

| Type | Manifestations |

| Mitral valve stenosis | Dyspnea on exertion, hemoptysis; fatigue. Atrial fibrillation on ECG, palpitations, stroke. Loud, accentuated S1. Low-pitched, diastolic murmur. |

| Mitral valve regurgitation | Acute: Generally poorly tolerated. New systolic murmur with pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock developing rapidly. Chronic: Weakness, fatigue, exertional dyspnea, palpitations. An S3 gallop, holosystolic murmur. |

| Mitral valve prolapse | Palpitations, dyspnea, chest pain, activity intolerance, syncope. Holosystolic murmur. |

| Aortic valve stenosis | Angina, syncope, dyspnea on exertion, heart failure. Normal or soft S1, diminished or absent S2, systolic murmur, prominent S4 |

| Aortic valve regurgitation | Acute: Abrupt onset of profound dyspnea, chest pain, left ventricular failure and cardiogenic shock. Chronic: Fatigue, exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, PND. Water-hammer pulse. Heaving precordial impulse. Diminished or absent S1, S3, or S4. Soft high-pitched diastolic murmur, Austin-Flint murmur. |

| Tricuspid and pulmonic stenosis | Tricuspid: Peripheral edema, ascites, hepatomegaly. Diastolic low-pitched murmur with increased intensity during inspiration. Pulmonic: Fatigue, loud midsystolic murmur. |

Mitral valve stenosis

Pathophysiology

Most cases of adult mitral valve stenosis result from rheumatic heart disease. Less common causes include congenital mitral stenosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Clinical manifestations

The primary symptom is exertional dyspnea due to reduced lung compliance. Fatigue and palpitations from atrial fibrillation may also occur. Heart sounds include a loud first heart sound and a low-pitched, rumbling diastolic murmur (best heard at the apex with the stethoscope bell). Other clinical manifestations are identified in Table 84.

Mitral valve regurgitation

Pathophysiology

Mitral valve function depends on the integrity of mitral leaflets, chordae tendineae, papillary muscles, left atrium (LA), and left ventricle (LV). A defect in any of these structures can result in regurgitation. Myocardial infarction with left ventricular failure increases the risk for rupture of the chordae tendineae and acute mitral regurgitation (MR).

Clinical manifestations

Patients with acute MR have thready peripheral pulses and cool, clammy extremities. A low CO may mask a new systolic murmur. Rapid assessment (e.g., cardiac catheterization) and intervention (e.g., valve repair or replacement) are critical for a positive outcome.

Patients with chronic MR may remain asymptomatic for many years until the development of some degree of left ventricular failure. Manifestations are identified in Table 84.

Mitral valve prolapse

Pathophysiology

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is an abnormality of the mitral valve leaflets and papillary muscles or chordae that allows the leaflets to prolapse, or buckle, back into the left atrium during systole. It is the most common form of valvular heart disease in the United States.

Clinical manifestations

MVP encompasses a broad spectrum of severity. Most patients are asymptomatic and remain so for their entire lives. Clinical manifestations may include those identified in Table 84.

Patients with MVP generally have a benign, manageable course unless problems related to MR develop. Table 85 provides a teaching plan for patients with MVP.

Table 85

Patient and Caregiver Teaching Guide

Mitral Valve Prolapse

When teaching the patient and/or caregiver how to manage mitral valve prolapse, teach the patient the following:Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|