Chapter 26 Using water for labour and birth

Learning outcomes for this chapter are:

1. To describe some of the history of using water for labour and birth

2. To integrate the literature that informs safe evidence-based care for women using water for labour and birth

3. To describe the principles and guidelines for using water for labour and birth

4. To support the use of water for labour and birth as a means of enabling midwives to be ‘with women’ and supporting physiological birth.

The key principles of a midwifery model of care that underpin this chapter are that:

• pregnancy and childbirth is a normal life event for most women

• midwifery care is woman-centred

• continuity of care should be provided throughout the entire childbearing experience

• the woman–midwife relationship is a partnership based on:

THE ROLE OF WATER BIRTH IN SUPPORTING PHYSIOLOGICAL BIRTH

Women know that they should avoid drugs and harmful substances during their pregnancies, yet the protocols for active management of labour subject them to a range of drugs and practices that often start a cascade of intervention, resulting in operative delivery. Wagner (cited in Hall & Holloway 1998, p 31) suggests that ‘Many midwives and the women in their care are becoming advocates of more natural forms of childbirth and demand care that is sensitive to the psychological needs of the individual and her family.’

The option to use water is one way of supporting women in labour without drugs, along with continuity of caregiver and the availability of private and peaceful surroundings in which to labour and birth. The demand for water immersion in labour and water birth has grown rapidly throughout the world over the past two and a half decades. Hall and Holloway (1998) suggest that this may be one reaction against medical control of childbirth. This is supported by Kitzinger (1996), who says that the use of warm water also seeks to change the dynamics of the care of labouring and birthing women, to give control back to them. She says warm water immersion and water birth are not just another ‘trendy’ technique, but rather an approach to childbirth that enables the birthing woman to have autonomy, by changing the environment and the quality of interactions between all those involved in the care.

Clinical point

Avoiding pharmacological pain relief

Increasingly, women want to find ways to manage the pain of labour naturally, thereby reducing the likelihood of requiring pharmacological pain relief, but are unsure about their ability to go through a labour without some help, especially women having their first baby. ‘I didn’t want to use drugs if I could help it but then I’m such a “wuss” when it comes to pain’ (Linda, in Maude 2003).

THE HISTORY OF WATER BIRTH

The first documented birth in water was reported in a French medical journal in 1805, when a woman, exhausted after a 48-hour labour, climbed into a warm bath to relax, giving birth to her child into the water shortly afterwards (Church 1989, cited in Richmond 2003a). In the following 150 years, the subject of water birth was rarely broached in the medical literature. Igor Tjarkovsky, the Russian water birth enthusiast, generated much interest in this method of birth in the 1960s, both within his own country and around the world, through claims that birth in water improved the psychic abilities of the baby (Zimmerman 1993, cited in Richmond 2003a). There are no data, however, to support this theory.

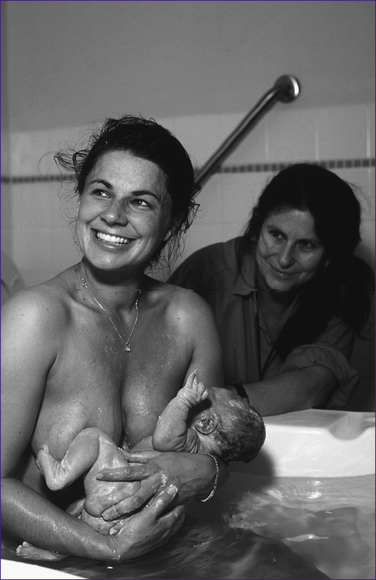

In France in the 1970s, Dr Michel Odent observed that women were attracted to the use of the shower or bath when in labour. As with most practitioners new to water birth, Odent’s initial experience was with a woman so completely relaxed in the bath that the baby was born before she was able to get out (Lichy & Herzberg 1993). After that first experience Odent began to offer water birth to all women who had long labours. In 1983, Odent published in The Lancet the summary of the outcomes of 100 water births at his alternative-birthing unit in Pithiviers, France. Odent’s article was one of the first major medical publications dealing with birth in water. While Tjarkovsky was concerned with the baby and its development, Dr Odent was more concerned with the labouring woman.

Following on from the work of Tjarkovsky, Leboyer and Odent, the practice of labouring and birthing in water gathered momentum in the 1980s within the home-birth community and the practice of domiciliary midwives. With the emergence of a spiritual movement that supported the notion of the dolphin and human connection and rebirthing, there was an increased demand for ‘water babies’ (Sidenbladh 1983). Inspired by enthusiastic women and midwives, labouring and birthing in water spread into birth centres and hospital maternity units in the 1990s. Its growing popularity is largely attributable to the women and families who have experienced the benefits of birthing this way.

THE FIRST WATER BIRTHS IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA

In New Zealand, to date there are no national data available as to water-birth rates and how women use pools and baths during labour and birth. Individual practice or facility audits report a 65%–75% rate of pool use in labour (Banks 1998; Cassie 2002) and a 25%–38% water-birth rate (Banks 1998; Fenton 2004). In New Zealand, Wanganui Hospital’s maternity unit led the country by openly using water immersion for birth. The first documented water birth at Wanganui occurred in November 1989; between July 1991 and December 2000 there were 916 water births in the maternity unit (Young 2001).

Clinical point

The first water births in Indigenous Australia and New Zealand

There is little early documented evidence of the practice of water birthing among the Indigenous women of Australia, although Odent (1990) says that some Aboriginal women on the western coast of Australia first paddled in the sea, then gave birth on the beach. There are stories of traditional birthing practices among the Māori of New Zealand where water was used. It was common for babies to be born on beaches in the Te Kaha area (Binney & Chapman 1986; Irwin & Ramsden 1995), and Makereti records the use of water to facilitate birth of the whenua (placenta) when it was delayed (Makereti 1986).

In 2008, the Midwifery and Maternity Providers Organisation (MMPO) in New Zealand produced its first report on MMPO midwives’ care activities and outcomes. The 2004 MMPO report (the data of 390 midwives, 9953 mothers and 10,064 babies) now contains information on the use of water during labour and/or birth. Almost one-third of women used water for pain management, although fewer than 10% of these women actually birthed in water. It is important to note that this equates to 3% of all births; therefore, while water is used frequently for labour pain management, its use for the actual birth is not common. The highest use of water in labour was reported for home births, with one in four of these using water for labour pain management. Primary maternity facilities also had a higher rate of water use for pain management, but their rate of water births was reported as one in six. Secondary and tertiary facilities had lower rates of water use for labour pain management and for birth (Hendry et al 2008).

Similarly, there is generally a lack of published data in Australia regarding the use of water for labour and birth, which is not indicative of its widespread usage. Labouring in water and births in water have been occurring at planned home births attended by home-birth midwives since the early 1980s (Lecky-Thompson 1989) and within hospital-based birth centres in Sydney and Melbourne since the early 1990s (Caplice 1999; Page 1994). Currently, the hospital facility audits report a water-birth rate of 35%–44% of total births at the Royal Hospital for Women in Sydney, which represents a steady increase since the inception of the practice in 1992. In addition, Australian independent midwives report a water-birth rate of around 60%–80% of total births (Caplice 2004).

USING WATER FOR LABOUR AND BIRTH: THE EVIDENCE

Within the Cochrane Library there is one Systematic Review (February 2004) combining the results of eight trials (2939 women) examining the effects of water immersion during labour. The only trial that researched birth in water was too small to determine outcomes for women and babies, and so was not included; nor were any studies of the third stage of labour in water. The reviewers concluded that there was a statistically significant reduction in women’s pain perception, and that the rate of epidural analgesia is reduced, which suggests that water immersion during the first stage of labour is beneficial to some women (Cluett et al 2002).

There was no evidence that the benefits were associated with adverse outcomes for babies or with longer labours. To date, there is insufficient evidence about the use of water immersion during the second stage to enable the formation of firm conclusions about the safety and effectiveness of giving birth in water. Water immersion during the first stage of labour can be supported for low-risk women (Cluett et al 2004).

To date, there are also no significant or multi-centred RCTs comparing birth in water with land birth, even though numerous authors have called for such rigorous testing. A commonly held belief has been that the ethical considerations of an RCT for water birth make the prospect of such a study unlikely (Woodward & Kelly 2004). However, a recent pilot study conducted by Woodward and Kelly (2004) to assess the feasibility of an RCT and the willingness of women to participate in such a trial has produced some positive results. The study showed that women were willing to enrol in an RCT comparing water birth with land birth and that randomisation does not necessarily affect women’s satisfaction with their birth experience. This research was thought to pave the way for the organisation of a multi-centred RCT to evaluate the differences between land and water births with large enough numbers to produce statistical significance. However, Keirse (2005) in a commentary strongly criticises the RCT by Woodward and Kelly, with particular reference to the limitations of a study where only 38% of participants received the treatment they were randomised to. Furthermore, Keirse highlights the investigator bias created by not including all the women that wanted a water birth in the preference group. Concern is also raised regarding the intention-to-treat analysis when only 25% of women randomised to birth in water actually did so, compared with the 50% of those who had chosen water (Keirse 2005).

Physiological effects

The calming and relaxing effect that water immersion has during labour and birth is well recognised. How this helps women to birth without exogenous pain relief and other forms of interventions was first described by Odent (1983). Church (1989) also proposed that water immersion decreases anxiety in the woman and that this works to reduce adrenaline levels, thereby encouraging the uninhibited flow of natural oxytocins and endorphins. A natural balance of pain and relaxation is achieved, and labour progresses normally.

Much of the research to date has attempted to quantify the absolute effect of pain relief afforded to the woman by water immersion during labour and birth. Women in trials have been asked to rank their level of pain using a visual analogue scale. The prospective RCT by Cammu and colleagues (1994) found no statistical difference between the absolute values of labour pain between the two groups of women in their trial. They reported that bathing provided no objective pain relief, but did have a temporal pain-stabilising effect, possibly mediated through the improved ability to relax in between contractions. This was supported in the historical cohort study by Aird and colleagues (1997), who found that labouring in water allowed greater relaxation of the mother during the first stage of labour, thereby allowing her to reach the second stage better prepared to give birth without assistance. The pain-relief effect of warm water immersion is probably associated with a reduced level of endorphins and catecholamines, as ‘there is a tendency to fall asleep in a comfortable tub’ (Odent 1997, p 415). The explanation for this effect is related to the ‘soothing warmth’, ‘support of the body’ and ‘pleasurable sensation’ of water, the effect of which stimulates the closing of the gate for pain at the level of the dorsal horn, and supports the notion that water provides women with a temporal stabilising effect (Cammu et al 1994).

The hydrothermic effect relates to the conduction of heat from the warm water through the skin, leading to peripheral vasodilation. The resultant release of muscle spasm contributes to the reduction in pain (Brown, cited in Richmond 2003a). The hydrokinetic effect refers to the feeling of weightlessness often described by women (Deschênes 1990). The combined effect of warmth and weightlessness contributes to women feeling more relaxed and less anxious (Ginesi & Niescierowicz 1998). The vasodilation of the peripheral blood vessels and the redistribution of blood flow when women are immersed in warm water during labour have been observed to contribute to a reduction in blood pressure (Church 1989; Nightingale 1994). A common concern has been that vasodilation and relaxation of uterine muscles might lead to an increased possibility of postpartum haemorrhage. However, numerous audits in units that use immersion in water for labour and birth do not support this (Caplice 2004; Garland & Jones 1994; Rosenthal 1991). It would seem that the natural processes already in place in the body are sufficient to counteract this theoretical problem (Richmond 2003a).

Clinical point

Women’s perceptions of pain

Women’s stories of their experiences of using water for labour and birth indicate that they do not necessarily use water to take the pain of labour away. Instead they see water immersion as helping them to cope with pain, and to reduce their fear of pain and of childbirth itself (Maude 2003). A woman in water may remain fearful and scared, but is presented with the opportunity to relax in between contractions to the extent that her labour may progress more rapidly. Relaxation enables women who use water to focus internally on what is happening to them, their body and their baby.

Clinical point

Relaxation and the effects of water immersion

Labouring in water may allow greater relaxation of the mother during the first stage of labour, allowing her to reach the second stage better prepared to deliver the baby on her own. ‘I almost fell asleep in between [contractions]. I just let my head loll on the side. I would just lie it against the side of the bath and I’d just about … go to sleep. I was so relaxed in between, it was really nice and it was nice to keep warm’ (Marion, in Maude 2003). Odent (1983) claims to have observed that water seems to help labouring women reach a certain state of consciousness where they become indifferent to what is going on around them. Odent continues to explore the biochemical and physiological effects of warm water immersion and concludes that, ‘when a parturient enters a bath at body temperature, there is immediate pain relief. This pain relief is probably associated with a reduced level of endorphins and catecholamines’ (Odent 1997).

What women say about water immersion

• Women feel more in control. Water reduces their anxiety about pain and about the process of childbirth itself.

• Women use water to cope with pain, not necessarily to remove or diminish it.

• Women feel more relaxed and the water promotes their comfort.

• Women feel sheltered and protected in the water, which promotes privacy.

• Women are able to move around more easily and feel supported by the water (Hall & Holloway 1998; Maude 2003; Maude & Foureur 2007; Richmond 2003b).

• Women using water in labour used rhythmic movements thought to facilitate descent of the fetus (pelvic rocking and swaying) (Stark et al 2008).

Stories of women’s experiences of using water for labour and birth have broadened our understanding of the meaning they make of the experience, and have demonstrated that the efficacy of water immersion goes beyond measurable outcomes. Being in water during labour and birth is not the end product; it is not the water itself that makes a difference. It is a shared philosophy and a shared belief in birth as a normal life event that supports women to use water. It is also the planning, preparation, education and anticipation of using water for labour and birth, supported by safe and judicious use that creates an environment that promotes relaxation, privacy and a release that enables and empowers women to maintain control. It appears that it is not necessary for women to actually give birth in the water to achieve these benefits (Maude 2003; Maude & Foureur 2007).

SAFETY AND EFFICACY OF USING WATER

Water temperature

The temperature of water used in labour and for birth has caused concern in relation to fetal outcomes. In the late 1980s, this concern focused on the potential dangers of temperatures below 37°C, with a suggestion that low temperatures may stimulate the baby to breathe (Gradert et al 1987; Lecky-Thompson 1989; Lenstrup et al 1987). Subsequently, attendants erred on the side of caution, maintaining pool temperatures at levels around 37–38°C. However, in 1994, maternal hyperthermia became an issue when two babies were born with perinatal asphyxia after the mothers were immersed in water for some hours during labour, as it was thought that the temperature of the water had been a contributing factor (Rosser 1994). This assumption was never proved.

Johnson (1996) explains that, as the baseline fetal temperature is normally 0.5–1°C above maternal temperature, the fetus is placed at risk when the mother experiences hyperthermia. The fetal oxygen demands increase, making the baby susceptible to fetal distress. In response to this information, guidelines have been set to reduce the risk of birth asphyxia in water: the recommended temperature of the water is no higher than 37.5°C, which is normal body temperature (Deans & Steer 1995; Duley 2001; Richmond 2003a). In contrast, in a paper on fetal hyperthermia, Charles (1998) explains that a maternal temperature rise of up to 1°C may be beneficial to the baby as there is an increase in oxygen transfer across the placenta; however, this research does not define temperature thresholds that might be considered too hot.

Geissbuehler and colleagues (2002) measured maternal and neonatal temperatures of women who birthed in water and compared them with those of women and babies who birthed on land. The authors concluded that birth in water did not pose a thermal risk to either mother or baby. Furthermore, they assumed that women self-regulate their body temperature according to changes in the water temperature and that this mechanism of self-regulation of core body temperature would be far superior to any water temperature guideline. There is no reason for practitioners to adhere to protocols that recommend keeping the water at a set temperature, other than the mother’s physical comfort. More recently, in support of Geissbuehler and colleagues’ proposition, Tricia Anderson (2004) suggests that practitioners give up their obsession with the temperature of the water and instead focus on ensuring that the woman has control over her environment and on facilitating her comfort. In a joint Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Royal College of Midwives statement on water immersion during labour and birth (2006), the authors concluded that there is wide variation in recommendations for the temperature of the water and supported the notion that there ‘may be more benefit to allow women to regulate the pool temperature to their own comfort’ (Alfirevic & Gould 2006). It would seem therefore more appropriate to check the woman’s temperature before she enters the pool and during the time that she is in the pool, while regularly checking with her about the temperature of the water. It is useful to maintain an ambient room temperature that is comfortable for the woman and to have supplies of cool water or ice chips and access to a fan.

Immersion and duration of labour

Studies investigating a reduction in the duration of labour in relation to water immersion have been inconclusive. In 1994, Garland and Jones analysed data from 209 primiparous women and 220 multiparous women and demonstrated a median and mean reduction in labour length, but since then other studies have been unable to replicate these findings. Schorn and colleagues’ (1993) prospective RCT of the use of warm water immersion by 93 women could not demonstrate a shortening of labour; however, the immersion was only for an average of 30–45 minutes. A retrospective case-control study by Otigbah and colleagues (2000) found that primigravidae having water births had shorter first and second stages of labour compared with controls (p < 0.05 and p < 0.005 respectively), reducing the total time spent in labour by 90 minutes (95% CI 31–148) (Otigbah et al 2000). Significantly shorter first stage of labour was also a finding of the review of 1600 water births by Thoeni and colleagues (2005). Other retrospective comparative studies show small decreases in length of labour. More recently, Cluett and colleagues (2004), in their RCT comparing water immersion with standard management for labour dystocia, reported water immersion as being of benefit, but the mean duration of labour was similar in both groups.