CHAPTER 2 Using the right type of evidence to answer clinical questions

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

2.2 Introduction

Qualitative research is in many ways the opposite. It is based on natural enquiry, for example, observing or interviewing people. Rather than trying to answer a question, qualitative research is designed to explore the meaning of things. For example, a quantitative study might ask the question ‘does this treatment work?’, whereas a qualitative study might ask ‘why does this treatment work and in what circumstances?’ Qualitative research usually employs an inductive approach in that it moves from the data collected to a theory. Qualitative researchers often immerse themselves in the research, since elimination of bias is not a primary aim.

2.3 Quantitative research designs

2.3.1 Epidemiology

Last’s Dictionary of Epidemiology describes epidemiology as ‘the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events in specified populations, and the application of this study to control of health problems’ (Last 2000:62).

Last (2000) uses the expression ‘health-related states or events’ since epidemiology now covers a wide range of health or health-related outcomes. In the earliest days of epidemiology, the main concern was study of infectious diseases. As these were gradually brought under control, attention then moved to acute diseases such as heart disease and cancer. More recently, we have focused on chronic diseases such as asthma and diabetes. We also now give priority to mental health problems, such as depression, and measures of quality of life. Finally, we are also interested in events such as accidents or birth defects. Clearly our understanding of disease has become much broader over time and this has shaped research.

Whenever we measure disease, we always do so with respect to the population at risk. For example, we might make the statement ‘there were 1700 new cases of prostate cancer in Australian males in 2006’. We chose the male population since only males can get prostate cancer. The male population would be the estimated mid-year male resident population as at 30 June 2006.

2.3.3 Bias

Bias is defined as a consistent deviation from the truth. More formally, it is defined as ‘deviation of results or inferences from the truth or processes leading to such deviation’ (Last 2000). There are dozens of different types of potential bias, including bias relating to the collection, analysis, interpretation, publication or review of data (Last 2000). With respect to quantitative studies, the main biases of interest include:

Unlike sampling error, bias cannot be reduced by increasing the sample size. One feature of quantitative studies are type I and II errors. A type I error occurs when the researcher, based on the study results, declares a treatment to be effective when it really is not. This is most often due to some type of bias. On the other hand, a type II error occurs when, based on the study results, a researcher declares a treatment to not be effective when it really is. This most often occurs when the researcher has used too small a sample size. In this case, the study is said to be underpowered.

2.3.4 Validity

The validity of a study (the word validity comes from the Latin validus, meaning strong) is the degree to which inferences or conclusions drawn from the study are warranted (Last 2000). We distinguish between internal and external validity. Internal validity is where any differences in outcome between study groups (apart from sampling error) can only be attributed to the hypothesised effect under investigation; in other words, the study is unbiased. External validity refers to how well it is possible to generalise the conclusions drawn from a study to other populations.

2.3.5 Confounding

Confounding is a special type of bias in which a measure of the effect of an exposure on risk is distorted because of the association of exposure with other factor(s) that influence the outcome under study (Last 2000). For example, in 1971, a case-control study by Cole found a link between coffee consumption and bladder cancer. In other words, the more coffee you drank, the more likely you were to get bladder cancer. However, it was later shown that heavy coffee drinkers were also more likely to smoke cigarettes, and it was the cigarette smoking causing the bladder cancer rather than the coffee drinking. Here we say that cigarette smoking confounds the relationship between coffee drinking and bladder cancer.

2.3.6 Randomised controlled trials

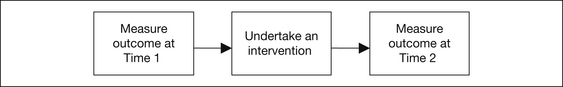

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) is the main type of experimental epidemiological study. In such a trial, subjects are randomly chosen from a population under investigation. One of the simplest possible study designs is the pre-post intervention study shown in Figure 2.1.

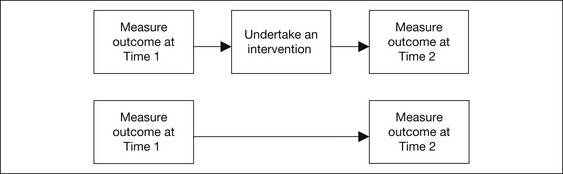

To eliminate maturation bias and regression to the mean, we can introduce a control group who do not receive the intervention (see Fig 2.2).

Because the RCT is considered to be the ‘gold standard’ of study designs, a number of organisations have been formed to review and collate the evidence for different interventions, focusing particularly on RCTs. This evidence is then stored in databases, including the:

We have already seen how randomly allocating patients to study groups reduces potential confounding bias. Ideally, patients, researchers and those assessing the outcomes should not know to which group each patient has been assigned. This is known as blinding. Research has shown that non-blinded studies are more likely to show a treatment effect; that is, they are likely to suffer from bias. Medical journals have liaised and established a standardised format for reporting the results of RCTs—this is known as the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement (see www.consort-statement.org). Researchers undertaking RCTs must first register their study protocol with a national registry of clinical trials (e.g. the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry; see www.anzctr.org.au/default.aspx) and then ensure that the paper presenting the results of the study exactly follows the CONSORT layout. This makes it easier for people undertaking systematic reviews to combine the results from different studies, a process known as meta-analysis. Registration of clinical trials also helps guard against publication bias; namely, that studies with positive results are more likely to be published than those with negative results.

2.3.7 Observational studies

There are many situations in which it is not ethical or even possible to undertake a randomised trial. For example, if you were interested in the relationship between marijuana use and schizophrenia, you could not ethically randomise subjects into those who must smoke marijuana and those who must not! In this type of situation, rather than deliberately expose people to a risk factor or intervention, we simply observe whether they have exposed themselves to it—hence the name ‘observational’ studies. The most commonly conducted observational studies are detailed on the next pages.

2.3.7.1 Cohort studies

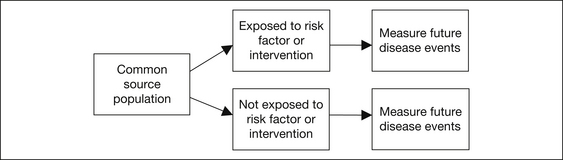

Cohort studies investigate the association between people exposed to a risk factor or intervention and those not exposed, and the subsequent development of disease. All subjects belong to the one defined source population or cohort. Cohort studies begin with an exposed and a non-exposed group and follow them over time to see who develops different diseases. The study design may be prospective (from now into the future) or retrospective (from the past until now). Figure 2.3 shows this in diagrammatic form.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree