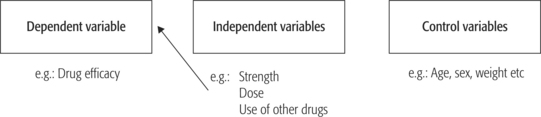

CHAPTER 18 Using research and evaluation in managing health services After studying this chapter, the reader should be able to: The word ‘research’ often alarms practising managers. This is surprising, considering that managers frequently use principles and processes basic to research methodologies in their everyday management practices. For example, Chapter 1 focuses on continuous learning in a rapidly changing environment; research is a prime resource. Research — both using existing relevant research and undertaking research directly — is an essential tool for keeping up to date with health service management developments, innovations and thinking, and is thereby a strategy for managing performance of services. Health services research underpins the process of basing decisions on evidence, at levels of policy, strategy and operations. The research process is basically concerned with collecting, analysing and interpreting evidence. The research process underlies a range of health service management competencies; for example: assessing consumer needs and priorities, and consumer satisfaction (see Chapter 5); decision-making and problem-solving (Chapter 9); services integration and coordination (Chapter 13); enhancing organisational performance (Chapters 15 and 16); and managing quality and risk (Chapters 16 and 17). Research as a health service management tool has long been advocated. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) Advisory Committee on Health Research reported in 1986 that the key to successful application of available health care technologies, so that services are relevant and acceptable to the community where services are provided, lies in the application of research (WHO 1986, p 73). The use of research as a tool to select and apply health care technologies to local needs was seen as relatively underdeveloped and poorly integrated into managerial processes, and explains the mismatch between advances in health science and associated technologies, and the improvement in health conditions for a majority of the world’s population. Health services in economically advanced countries also face major pressures. Financial and competitive issues in particular put pressure on organisations to efficiently deliver high-quality health services. The application of technologies and ways of delivering health care need to be continually evaluated in order to maintain a competitive advantage in a resource-constrained, rapidly changing environment. For this purpose, health services research is advocated as a key element in the organisational strategy of major health service organisations (Smith et al 1988). Health services research is also important to small community health service and social support agencies (Anderson et al 1999). In an environment of decentralisation and de-institutionalisation, voluntary, not-for-profit community organisations deliver a growing volume of health and social support services. While individually small, collectively these voluntary organisations administer a significant portion of health service funds, yet are vulnerable by the nature of their funding and the capricious environment. Anderson et al (1999) argue that for these organisations to provide services in the most effective and efficient way, research is an important, though under-utilised, tool. At another level — the governmental level of formulating health policy and, in the past two decades particularly, of reforming health systems — questions have been asked about the weak relationship of health services research and decision-making (Davis & Howden-Chapman 1996). There is a dearth of examples of researchers and research results influencing policy formulation. This is partly because of limitations imposed by the scope and design of research. Continuing paradoxes between research and the practice of health care (medicine, therapeutic practice, health policy and health services management) could be addressed by cultivating a much closer working relationship between researchers and major potential users of research, health service managers included. The renewed call to incorporate health services research into the organisation and management of those services at strategic and operational levels, in order to meet international and national goals for health services delivery and health gain, is reflected in the publication of an anthology of health services research in 1992 by the Pan American Health Organization (the Americas’ regional office of WHO) (White et al 1992). This massive volume comprises a collection of 100 studies published from 1914 onward, selected because they represent important research-based contributions to the theory and practice of health management. White et al (1992, p xxi) observe that in reflecting the developing field of health services research: White et al (1992) state that the field of health services research — an ‘embryonic, dynamic and increasingly important field of research’ (p xxiv) — broadly covers the relationship between a population and its health services. While medical science developed slowly through the ages, health status improvements were, until relatively recently, attributable mainly to improvements in living standards and nutrition, and developments of social, physical and economic environments. Recent dramatic advances in medical knowledge and technology have been accompanied by increasing involvement by governments in providing health care, and a need to know whether these services were effective, acceptable, and delivered efficiently and equitably. More recently the focus has been on demonstrating that investments in health services result in benefits: health gain for the population, disease management for individuals, management of quality and risk. In other words, research is driven by concern that intended outcomes are explicit and demonstrable, and that the practices of medicine, health care and health service delivery are based on evidence, not on traditions and historical practices. The field of health services research has emerged in the wake of these developments. Biomedical research, in contrast, is traditionally concerned with causes, consequences, diagnosis and treatment of disease. However, the boundaries between health service and biomedical research are becoming blurred in current research interest in outcomes — and evidence-based medicine, in which medical interventions are linked to resource utilisation. White et al (1992, p xix) define ‘health services research’ broadly as ‘the study of the relationships among structures, processes and outcomes in the provision of health services’, with a subset of ‘health systems research’ that is concerned with the ‘set of resources that a society mobilizes and institutions that it organizes to respond to the needs of its population’. However, these distinctions are by no means made consistently, and are used synonymously. White et al (1992) point out that of the two terms ‘health systems research’ (in the broad sense in which these authors define it) is the more recent, and ‘health services research’ has been — and sometimes is still — used to refer to the widest possible research agenda. For example, WHO (1986) uses the term ‘health systems research’ to cover government programs, the private sector, indigenous practitioners, and other sectors and factors that influence health. In contrast, Smith et al (1988) view health services research narrowly, as the ‘study of the organisation, economics, financing, and delivery of health services’ (p 48). The diversity and multidisciplinary character of health services research offers strengths and creates problems. Scientific endeavour that is conceptually and methodologically located in complex, untidy social systems stands a good chance of coming up with valid, useful answers reflecting that complex, dynamic reality. Indeed, the advancement of knowledge is stimulated when disciplinary boundaries are crossed and cross-fertilisation of ideas occurs. At the same time, problems lie in the complexity and variety of health services research: it is easy to lose focus and direction in complex, multi-method and interdisciplinary study. The difficulty of overcoming boundaries that separate disciplines may explain, at least in part, the disappointing scope and usefulness of some studies and the limited influence of research on health policy and health care practice. Irrespective of these difficulties, health service organisations stand to gain from investing in health services: high-quality staff members are attracted and retained; a culture of critical reflection and analytical thinking is promoted; innovations and marketable products can be developed; and organisational flexibility and performance are supported. There are also costs, including resource investments without a guaranteed return, trade-off between researchers’ time spent on research and other duties, and conflicts between organisational and researcher philosophies regarding use of research results (Smith et al 1988). For managers of health services and students of health services management, these issues, while interesting and important, can also be problematic. For example, from the potentially vast field of inquiry, where should the practising or student manager, policy maker and decision maker go to locate potentially useful research? How can these users evaluate reported research or put in place a research project, in order to advance the mission of a given health service, organisation or health system? Anderson et al (1999) found that directors of local health services organisations felt that there was simply too much potentially useful information to use effectively, and they lacked the resources to access and interpret it. In spite of these difficulties, health services and policy decisions should not be made without the evidence to support change. Further, benefit needs to be sufficiently large in relation to risks and costs (Sheldon et al 1998). Some writers in the field have also asked these questions. For example, McKee and Britton (1997) asserted that effective health decision makers must be able to use published research, and in view of the dramatic increase in the volume of research it is necessary to develop skills to collect the research evidence on which to base decisions. An important primary skill is the ability to conduct reviews of literature and interpret reported research: competence in systematically reviewing literature is fundamental not only to establishing evidence but also as the foundation to conducting research personally. There are well-documented examples of where evidence has been ignored, where major decisions have been made without evidence, and where evidence is weak for such reasons as poor research design, inadequate sampling, and reporting biases (Davis & Howden-Chapman 1996, McKee & Britton 1997). At all levels of the health system there is an emphasis on basing health care on evidence. This occurs at levels of individual treatment decisions, health services, purchasing services and policy (Sheldon et al 1998). Systematic reviews have been shown to provide more reliable research evidence than non-systematic reviews and isolated studies. Fortunately for today’s health services manager the sheer volume of research in relevant areas has been collected in a number of accessible databases. An example is the Cochrane Library, which carries out and regularly updates meta-analyses of evidence, and electronic databases such as MEDLINE and EMBASE. While databases enable a far easier accessing of potentially relevant articles, the onus is still on the reader to intelligently interpret the reported research and judge whether its findings are relevant to the current health management problem, or health service context and issues. Useful questions to ask of any research article include: Very tight budgetary and time constraints within which health service managers operate, along with the frequent changes in funding agency priorities, often restrict the use of research to support decision-making. Exacerbating the problem, researchers, health services managers and policy makers tend to work in parallel rather than together. The result is that managers and policy makers may ignore or be unaware of relevant research and researchers may be unwilling to compromise academic independence and research rigour in order to work alongside leaders in the field. A solution to the problem is the nurturing of research partnerships (Davis & Howden-Chapman 1996). Research conducted without reference to potential users can result in a mismatch between the research and decision makers. Further, the evaluation of research-derived evidence can differ according to criteria used; for example, health service managers will look for different benefits than clinicians (Sheldon et al 1998). While the previous section focused on theories and concepts underpinning health services that influence, and are influenced by, research, this section considers the theories and concepts influential in the process of research. Health services research reflects the major research paradigms (ways of seeing the world) in the social sciences (that have in turn heavily influenced research methods in management), and to some extent the biomedical sciences. It is these paradigms influencing social research which are the focus of this section. ‘Paradigm’ is a term coined by Kuhn in (1962) to describe dominant steps in the progress of science, and is loosely used in social sciences to refer to a set of beliefs and views about the world (Lincoln & Guba 1985). Easterby-Smith et al (1991, pp 9–10) conceptualise research as comprising three aspects: the philosophical, political and technical. The technical aspects refer to the collecting and analysing of data, explained in research methodology texts. This is briefly discussed later in this chapter, in the section titled ‘Key elements common to most research projects’. The political aspects concern the context of research: the purpose and how the research may be used, as well as the relative power between the sponsor and other stakeholders, and the researcher. These aspects emerge in this chapter in the section titled ‘Evaluation as a health management tool’. The philosophical aspect influences views of the world and the choice of research paradigm as well as the confidence in research, discussed in the following section. Philosophers, scientists and those in pursuit of knowledge have for centuries debated the relationship between theory and evidence. In the social sciences, where health services research is generally located, the debate has centred on two competing traditions: positivism, and the methods described broadly as interpretive or naturalistic inquiry, including phenomenology (Easterby-Smith et al 1991, Lincoln & Guba 1985, Shipman 1997). Managers undertaking research as well as those using research would be wise to keep an open mind when reflecting on whether research questions should be approached from this interpretive position or whether answers are more likely to be obtained from positivistic inquiry. The choice of positivist or interpretive research, or indeed a combination of the two, depends on the nature of the subject of the research, and on the research questions the study will answer. Each is now briefly explained, and examples of applications given. As the social sciences became established alongside physical sciences, the dominant paradigm was the reductionist, hypothetico-deductive (hypothesis testing) model favoured in physical sciences. The philosophy of science that has become known as positivism — the term established by Comte in 1848, also known as ‘scientistic’ and characterised by the scientific method (Shipman1997, pp 22–3) — is based on a number of assumptions. Reality is external and objective, and can be known only through observation of objective facts. The observer must be independent of and value-free regarding what he or she is observing, and the aim of research is to establish causality — universal explanatory laws — that can be generalised and operationalised to allow facts to be measured quantitatively (Easterby-Smith et al 1991, p 23). The aim of establishing causality among variables led to a range of sophisticated techniques; for example, to isolate and manipulate factors being tested, to sample populations, to develop and test research instruments, and to statistically test results to determine significance. It should be possible to replicate well-constructed research and achieve the same results, and to generalise the findings from the sample to the population. Positivism has been strongly influential in epidemiological research and in health services research, where a constant relationship between variables is expected, for example, utilisation projections based on historical data and demographic trends, efficiency based on length of stay and bed-use rates. Randomised controlled trials are widely regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for establishing the efficacy of treatments. Figure 18.1 (later in the chapter) shows the relationship between variables that researchers in this paradigm work with. Alternatives to positivistic inquiry have as their starting point alternative views of the world. The central task of interpretive research is to interpret data, those subjective realities and social constructions related by research participants, in the context of the complex whole. Several key differences flow on. These alternatives do not assume that reality is objective. Rather, that reality is socially constructed and imbued with meaning by the actors. This competing paradigm incorporates a range of methods characterised by naturalistic design and qualitative data and include ethnographic, interpretive, phenomenological and grounded theory research. Researchers accept that the world is socially constructed and therefore reality is subjective. The task of the researcher is to focus on meanings rather than observable facts, to accept that he or she is part of, and affects, the social world being observed, and to interpret meanings ascribed to the social world (Shipman 1997). Interpretive inquiry designs might be employed in health services research when a phenomenon is not well understood, particularly when human and organisational behaviour are at issue: needs analysis, why a particular community does not use or benefit from a given service or intervention, case studies and experiencing illness are all examples. These methodologies are useful for understanding attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of patients and professionals, health organisational contexts and interactions, and phenomena such as pain and clinical communication. For further information see Lincoln and Guba (1985); Easterby-Smith et al (1991); Shipman (1997); Grbich (1999). Table 18.1 compares the attributes of the positivist and interpretive research paradigms. Table 18.1 Positivist and interpretive research paradigms compared

Demonstrate understanding of the kinds of research problems best researched by different theories, research strategies and methodologies.

Demonstrate understanding of the kinds of research problems best researched by different theories, research strategies and methodologies.

INTRODUCTION

THE CONTRIBUTION OF HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH TO MANAGEMENT

HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH DEFINED

MULTIPLE FOCUSES OF HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH

Policy formulation and decision-making

USING RESEARCH IN HEALTH SERVICES MANAGEMENT

Were the procedures for collecting and analysing data sufficiently clear for the reader to evaluate results in the light of the methodology?

Were the procedures for collecting and analysing data sufficiently clear for the reader to evaluate results in the light of the methodology?

THEORIES AND CONCEPTS UNDERPINNING RESEARCH STRATEGIES AND METHODOLOGIES

Philosophy of research

Positivist inquiry

Interpretive and naturalistic inquiry

ATTRIBUTE

POSITIVIST PARADIGM

INTERPRETIVE PARADIGM

Design and time frame

Cross-sectional and longitudinal.

Most likely to be conducted over an extended period.

Setting

Experimental laboratory or quasi-experimental conditions.

Conducted in the natural setting.

Researcher

Maintains objectivity and non-intrusion in the study.

Principal research instrument bringing values, interactive and interpretive skills and tacit knowledge to bear on the study.

Selection of participants

Representative sample of subjects.

Purposive selection of a small number.

Sufficiently large to provide data generalisable to the population under study.

The participants’ experiences and perspectives are emphasised.

Character of the data

Social phenomena tend to be reduced to a limited number of variables.

Qualitative in character, and often described as ‘rich’ or ‘thick’.

Data analysis

Favours the development and testing of propositions and hypotheses from extant theory.

Interpretive theory emerges from the data.

Conclusions

Statistical reporting is favoured.

Particular to the phenomenon being studied and stated in context so that the relationships of meaning, contexts and particularity are preserved; for example, by using case study and narrative modes.

Validity

Ideally, subjects are not aware they are being researched or of the true purpose of the research for fear it may confound and change the findings.

Social worlds constructed by participants are viewed as valid, and participants have opportunity to confirm and verify interim findings.

Boundaries

Clearly defined from the outset of the study.

Not ‘set in concrete’ at the outset of the study, are allowed to emerge in the light of emergent data and its interpretation, and in negotiation with participants. ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Using research and evaluation in managing health services

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access