Urinary problems

Just the facts

Just the factsIn this chapter, you’ll learn:

anatomy and physiology of the urinary tract

assessment of the child with a urinary problem

diagnostic tests and treatments used for urinary problems

specific acquired and congenital urinary disorders.

Anatomy and physiology

The key structures of the urinary system are the kidneys and urinary tract.

|

Kidneys

The kidneys are bean-shaped organs located near the middle of the back. Their primary functions are to filter waste products from the blood and form urine and send it to the bladder through the ureters. Other functions of the kidneys include regulation of volume, electrolyte concentration, acid-base balance of body fluids, and blood pressure and support of red blood cell (RBC) production (erythropoiesis).

The kidney is divided into two distinct areas:

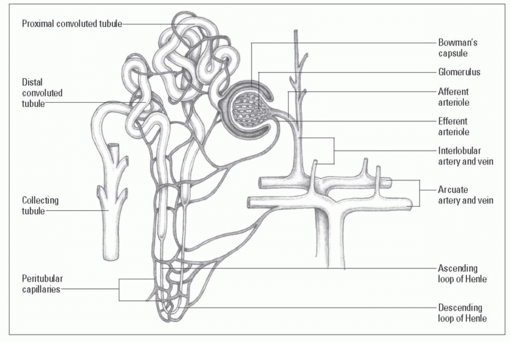

A closer look at a nephron

The nephron is the kidney’s basic functional unit and the site of urine formation:

Blood flows through the interlobular artery (running between the lobes of the kidneys) to the afferent arteriole, which conveys blood to the glomerulus.

Blood flows through the interlobular artery (running between the lobes of the kidneys) to the afferent arteriole, which conveys blood to the glomerulus. Blood passes through the glomerulus into the efferent arteriole and into the peritubular capillaries, venules, and the interlobular vein.

Blood passes through the glomerulus into the efferent arteriole and into the peritubular capillaries, venules, and the interlobular vein.

|

Nephrons

Nephrons are the kidney’s functional units. These microscopic structures form urine. (See A closer look at a nephron.)

A child acquires the adult number of nephrons shortly after birth, although these structures continue to mature throughout early childhood. The renal corpuscle within the nephron filters

blood plasma. The renal tubules within the nephron allow the filtered fluid to pass through on its way to the bladder.

blood plasma. The renal tubules within the nephron allow the filtered fluid to pass through on its way to the bladder.

Multitasking kidneys

To produce urine, the various parts of the kidney perform three basic functions:

While waste products and excess fluids are filtered out of the blood for elimination, necessary fluids, electrolytes, proteins, and blood cells are retained (resorbed) into the bloodstream.

Urinary tract

The urinary tract consists of the bladder, urethra, and ureters. The bladder is a balloon-shaped pouch of a thin, flexible muscle, in which urine is temporarily stored before being eliminated from the body through the urethra. Urine is produced by the kidneys and passed into the bladder through two ureters, one from each kidney.

A friendly nudge

Peristaltic contractions within the ureters push urine from the kidneys toward the urinary bladder. A valve mechanism prevents urine from backing up into the kidneys as the bladder fills. When the bladder is full:

The micturition reflex is triggered, and nervous innervation causes relaxation of the internal sphincter muscle.

Relaxation of the internal sphincter muscle sends a message to the person’s conscious mind to indicate the need to void.

The person then releases the external sphincter, and urine passes through the urethra and out of the body.

Any volunteers?

Voluntary control of these urethral sphincters usually occurs in a child between ages 18 and 24 months. However, the psychological readiness to initiate toilet training may develop much later.

Urine

Urine is a liquid waste product that’s filtered out of the blood by the kidneys, stored in the bladder, and expelled from the body through the urethra during urination. About 96% of urine is water, and the other 4% is waste product.

A child’s bladder can hold 1 to 1.5 oz of urine for every year of age. Average urine output will vary according to age. (See Urine output in children.)

Urine output in children

This chart shows the average volume of urine output per 24 hours for children according to age.

|

Diagnostic tests

Diagnostic tests commonly used to assess urinary system problems in the pediatric population include:

urinalysis and urine culture

blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels

X-ray of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder (KUB)

excretory urography

voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG)

renal ultrasound

renal biopsy.

Urinalysis and urine culture

Urinalysis determines urine characteristics, such as specific gravity, pH, and physical properties (color, clarity, odor), and detects the presence of RBCs, white blood cell (WBCs), casts, and bacteria.

Culture on a plate

In a urine culture, the urine specimen is placed on a medium and bacteria that may be present are allowed to grow and are then counted. As soon as bacteria are identified, sensitivity testing can determine which antibiotics would be most effective for treating the infection.

Catch ‘em while you can

Specimens for urinalysis and urine culture are typically obtained as clean-catch specimens but may also be obtained from an infant’s diaper (urinalysis only), a urine collection bag for infants and young children, bladder catheterization, or a suprapubic bladder tap.

Nursing considerations

Nursing considerations differ according to the child’s age and gender. For boys, the head of the penis and the urinary meatus must be cleaned. For girls, the urinary meatus must be cleaned, carefully washing between the labia.

|

Lather up, rinse away

For both boys and girls, soapy water, which is then rinsed away, is usually used for cleaning. If an antiseptic towelette is provided, it may be used without rinsing afterward. In addition, follow these steps:

Instruct the child or parents on how to clean the penis or meatus.

Instruct the child or parents on how to collect the urine specimen by starting to urinate into the toilet bowl to clear the urethra of contaminates and then catching 3 to 6 oz of urine in a sterile container.

For neonates and infants, apply a urine bag to obtain a clean specimen; the bag fits over the perineum in females and the penis (and perhaps the scrotum) in males to catch urine as the infant voids (instruct the parents to inform you as soon as the child voids, so the container can be removed and fecal contamination can be avoided).

When obtaining a urine specimen from a catheterized child, don’t take the specimen from the collection bag; aspirate a specimen through the collection port in the catheter with a sterile needle and syringe.

Keep it clean

A clean-catch specimen may be needed to diagnose a urinary tract infection (UTI). In addition to the procedures used for routine urinalyses, it’s useful to:

Instruct the child or parents to use an antiseptic solution to clean the urethral meatus (with a prepared towelette or a cotton ball soaked in the solution); the urethral meatus should be cleaned at least three times, using a new towelette or cotton ball each time.

Stress to the child and parents the importance of not touching the inside of the sterile container to maintain its sterility.

Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine

Serum BUN and creatinine levels are obtained from blood samples drawn from venipuncture.

BUN levels can provide a great deal of information about kidney function; they measure the blood nitrogen that’s part of the urea resulting from catabolism of amino acids (proteins). When the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) reduces suddenly and severely, the BUN level rises suddenly.

Plasma creatinine levels become elevated when there’s catabolism of creatinine phosphate in skeletal muscles. An elevation in these levels indicates poor renal function.

The ratio between BUN and creatinine may also be examined. The ratio is usually between 10:1 and 20:1. Results vary with muscle damage, as in the case of a crushing injury or degenerative muscle disease.

Nursing considerations

Nursing considerations are aimed at making venipuncture less stressful for the child.

Use lidocaine and prilocaine (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics [EMLA]) cream or some other form of topical anesthetic to make it easier and less traumatic to draw blood from a child; remember to apply it at least 1 hour before drawing blood.

Allow the parent to be present, and allow the child to hold a comfort object, such as a stuffed animal or blanket, during the venipuncture.

Follow dietary orders as necessary; sometimes, when BUN levels are elevated, protein intake may need to be limited.

KUB radiography

KUB assesses the size, shape, position, and possible areas of calcification of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder. A KUB may be required as a first step if a problem with these structures is suspected.

Nursing considerations

The nurse should help the child remain quiet and lie still during the X-ray. Tell the child that this is his “job” and that there’s no “hurting part” involved.

Depending on facility policy, parents may be able to remain in the radiology room with the child. Instruct them that they must be shielded from radiation by wearing a lead apron.

|

Excretory urography

Excretory urography is a form of X-ray of the lower urinary tract, during which a dye is injected intravenously (I.V.). A series of X-rays is taken as the dye passes through the bloodstream, is filtered through the kidneys, passed on through the ureters into the bladder, and then through the urethra to be eliminated from the body.

Nursing considerations

Begin by explaining the reason for the test to the child and parents and telling them what to expect.

Prepare the child for insertion of the I.V. line and reassure him that it’s the only needle stick he’ll experience.

Assess for a history of allergies to dyes, iodine, shellfish, or eggs because of the use of an iodine-based contrast medium.

Administer a bowel preparation as ordered; the colon must be emptied because a full bowel won’t allow proper visualization of the urinary tract.

Insert an I.V. line to allow for the injection of the dye.

Explain to the child that he may feel warm or a bit woozy when the dye is injected; reassure him that this is normal and that the feeling will pass quickly.

On the day of the test, allow only clear liquids to be consumed until after the test is completed.

Voiding cystourethrogram

VCUG is an X-ray of the bladder and the lower urinary tract. A catheter is inserted through the urethra into the bladder, and a water-soluble contrast medium is injected through the catheter. The catheter is then withdrawn, and X-ray images are taken as the bladder is emptied.

This test is performed to determine if there are abnormalities of the lower urinary tract, particularly vesicoureteral reflux, a condition that increases the risk of or prolongs a UTI. Sedation is rarely required, nor is it desirable, because the child must urinate during the test.

|

Nursing considerations

VCUG can be a difficult test for children. Insertion of a catheter can be uncomfortable and embarrassing. The child will be asked to void during the test, and to do so without going into the bathroom, which can be confusing to a child who has recently been toilet trained. What’s more, the thought of voiding in the X-ray room in full view of the technician can be embarrassing. Reassure the child that the hospital staff realizes he knows how to use the bathroom and that he’ll be urinating during the test only because he’s being asked to do so (explain why this is necessary).

In addition, follow these steps:

Explain the reason for the test and prepare the child for insertion of the catheter.

Before the test, make sure the child is dressed in comfortable clothing and is wearing no metal objects.

Assess for a history of allergies to dyes, iodine, shellfish, or eggs because of the use of an iodine-based contrast medium.

Tell the parents of infants and young children that the child may be wrapped tightly in a blanket to help him lie still during the procedure.

Assure the parents that the amount of radiation received by the child is minimal.

Inform the parents that a VCUG can’t be performed while the child has an active UTI.

Behind closed doors

Insert a urinary catheter just before the test; provide as much privacy as possible by closing the door or drawing curtains, and allow a parent to remain in the room if the child desires (depending on the child’s age, a nurse of the same sex may be the best person to insert the catheter).

After the procedure, remove the urinary catheter and encourage the child to drink fluids to reduce burning on urination and to flush out residual dye; pouring a glass of very cold water over the genital area during the first few voids after catheter removal helps to minimize burning.

|

Renal biopsy

Although renal biopsy isn’t performed routinely in children, it may be used to evaluate decreased kidney function, persistent blood in the urine, or protein in the urine. It may also be performed to evaluate the functioning of a newly transplanted kidney.

In renal biopsy, a needle is inserted through the child’s flank under ultrasound guidance. A small specimen of kidney tissue is withdrawn and sent for microscopic study.

Nursing considerations

Prepare the child and parents for the procedure, which can be frightening. Use a doll to show the child how it will be done. In addition, follow these steps:

Reassure the parents that ultrasound will allow the doctor to see exactly where he’ll be inserting the needle and will prevent damage to other organs.

Provide analgesics as ordered.

Assist with positioning and holding the child throughout the procedure.

Treatments and procedures

Common treatments and procedures used in the care of a child with a urinary disorder include bladder catheterization, hemodialysis, kidney transplantation, and peritoneal dialysis.

Always prepare children for treatments and procedures with an age-appropriate explanation of what to expect. When treatments and procedures involve surgery, preparation should include an explanation of the anesthesia and what to expect postoperatively.

Bladder catheterization

Bladder catheterization may be performed for diagnostic or treatment purposes. In this procedure, the urethral meatus is thoroughly cleaned and an appropriate-sized catheter is inserted through the urethra into the bladder.

Insert and drain

In intermittent catheterization, a straight catheter is inserted and a urine specimen may be taken; the catheter is removed after the bladder is drained.

Insert and inflate

If the catheter is to remain in place, an indwelling catheter, also called a Foley catheter, may be used and attached to a drainage bag for urine collection. An indwelling catheter has an inflatable balloon near its tip to hold the catheter in place in the bladder.

Nursing considerations

Remember that catheterization can be uncomfortable and embarrassing for a child. The older child may feel more comfortable when a same-sex nurse inserts the catheter. The younger child may be confused and fearful if he has been told it’s wrong for anyone to touch his “private parts.” Have the parents explain to the child that this situation is different.

To minimize trauma, follow these steps:

Educate the child and parents about the purpose of the catheterization; if it’s being done to obtain a sterile specimen, explain why this is preferable to a clean-catch specimen.

Prepare the child to facilitate the procedure and ease the child’s fears; use a doll to show him what will happen.

Be sure to choose the appropriate-sized catheter. (For a premature neonate, a size 5 French feeding tube may be used; for a larger infant or a small toddler, use a size 8 French feeding tube; for children ages 4 and older, use a size 8 French to 14 French catheter.)

Provide as much privacy as possible; close the door, draw the room divider curtain, and allow the child to keep on as much clothing as possible.

Allow the parent to be present if the child desires.

Give the child coping mechanisms to deal with discomfort (such as “Squeeze your mother’s hand if it hurts,” or, “Count to 10 and the hurting part will be over”).

Use distraction techniques to help keep the child’s mind off of what is happening. This can be accomplished with toys with which the child likes to play or with bubbles. Just be sure to keep everything clear of the sterile field that has been set up.

|

Generous and gentle

When inserting the catheter:

Clean the urethral meatus three times with an antiseptic swab, using a different swab each time.

Generously lubricate the tip of the catheter and gently insert it through the urethra into the bladder until urine returns and is collected in the sterile specimen container.

If the catheter doesn’t easily enter the meatus, use a smaller catheter; never force it into the urethral meatus.

If performing an intermittent catheterization, gently remove the catheter after the bladder is drained; clean off the antiseptic and lubricant with water.

If inserting an indwelling urinary catheter, insert the inflatable balloon with sterile water and gently pull on the catheter to make sure it inflated; next, connect the catheter to the closed drainage system.

|

Hemodialysis

Hemodialysis involves the use of a machine to clean waste products from the bloodstream if the kidneys are severely damaged or have failed. The blood travels through tubes to an artificial kidney in the machine, and waste products and excess fluid are removed from the body. The purified blood then flows back to the body through another set of tubes. Ideally, this would be done in a pediatric dialysis center.

To stick or not to stick

The child on hemodialysis may have a double-lumen central catheter in place in his chest to serve as a site for blood removal. Children needing long-term dialysis may have a subcutaneous graft, anastomosing a vein and an artery. This graft reduces the risk of infection but means the child will need two venipunctures each time dialysis is performed. EMLA cream should be used to reduce discomfort.

|

Nursing considerations

Provide diversional activities to prevent boredom, such as games, music, drawing or coloring materials, and videos; encourage a family member to stay with the child. In addition, follow these steps:

Weigh the child before beginning hemodialysis.

If the patient has a subcutaneous graft, check the blood access site every 2 hours for patency and signs of clotting; don’t

use the arm with this site for taking blood pressure or drawing blood.

During dialysis, monitor vital signs, clotting times, blood flow, the function of the vascular access site, and arterial and venous pressures.

Look out for losses

Watch for complications, such as septicemia, embolism, hepatitis, and rapid fluid and electrolyte loss.

After dialysis, monitor vital signs and the vascular access site; weigh the patient and watch for signs of fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

Use standard precautions when handling blood and body fluids.

|

Kidney transplantation

Kidney transplantation involves replacing a patient’s diseased kidney with a healthy kidney from another person. The donor kidney may come from a living donor or a cadaver donor. Although hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis are life-preserving procedures and may even be carried out in the home, kidney transplantation is the preferred method of renal replacement therapy in the pediatric population because it offers the opportunity for a normal life.

Nursing considerations

By the time a child undergoes kidney transplantation, he most likely has a long history of procedures and hospitalizations. The child should be given as many choices as possible; a choice as simple as which arm to use for a blood draw can help to give the child a sense of control.

In addition, follow these steps:

Provide emotional support and guidance to the child and parents; prepare them for the procedure, including what will occur preoperatively, during the procedure, and postoperatively.

Arrange for the child and his parents to tour the intensive care unit and meet the nursing staff before the transplantation.

Administer immunosuppressive medications as ordered; a child who will have or has had a kidney transplant will be taking immunosuppressive medications to decrease the risk of organ rejection.

Monitor for signs and symptoms of infection; while immunosuppressed, the child is at increased risk for infection.

|

Peritoneal dialysis

In peritoneal dialysis, the blood is cleaned of waste products and excess fluids using the lining of the abdomen as a filter. Peritoneal dialysis is especially useful for children who are poor risks for vascular access and for those who live far from a medical center.

This procedure includes these steps:

A peritoneal dialysis catheter is inserted through a small abdominal incision or a puncture hole into the peritoneal cavity. The catheter is then connected to fluid bags and tubing.

A cleaning solution is drained from a bag into the abdomen.

Fluids and waste products flow through the lining and are “caught” by the dialysis fluid.

This fluid is then drained from the abdomen, taking the extra fluids and waste products with it.

Nursing considerations

Prepare the child and parents for the insertion of the catheter into the abdominal cavity. Make sure a valid informed consent form has been signed and included in the patient’s chart. In addition, follow these steps:

Monitor the child’s reaction to the sedation, anesthesia, and pain management regimen.

Make sure strict sterile technique is used at all times during catheter placement and peritoneal dialysis.

Monitor the child’s response to the therapy.

Make the child as comfortable as possible and provide sufficient rest periods.

Assess for bleeding from the catheter insertion site.

Maintain patency of the peritoneal dialysis catheter; keep it in place, without kinks or pulling, and with the fluid bags at the correct level.

Monitor for signs of infection at the insertion site.

Urinary disorders

Urinary disorders that may affect children include acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, chronic glomerulonephritis, congenital urologic anomalies, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), nephrotic syndrome, renal failure (acute and chronic), and Wilms’ tumor.

Acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis

Glomerulonephritis is an inflammation of the tubules of the kidneys (glomeruli), which filter waste products from the blood. When this inflammation follows an infection with streptococcal bacteria (most commonly via strep throat), it’s called acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. It’s most commonly seen in boys between ages 3 and 7 but can occur at any age. Up to 95% of children recover fully; the rest may progress to chronic renal failure.

An interesting point: The relationship between acute glomerulonephritis and scarlet fever was first recognized as early as the 18th century. Its relationship with hemolytic streptococcus was identified later in the 1950s.

What causes it

Acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis typically follows a group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection of the respiratory tract. Less commonly, it may follow a skin infection such as impetigo.

How it happens

The disease usually begins about 1 to 6 weeks after a streptococcal infection, although 2 weeks is the most common time of onset.

Clumping with the enemy

In this immunologic disorder, antigens from streptococci clump together with the antibodies that killed them and become trapped in the tubules of the kidneys. The tubules become inflamed, and edema of the capillary walls decreases the amount of glomerular perfusion. The kidneys then become incapable of filtering and eliminating body wastes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access