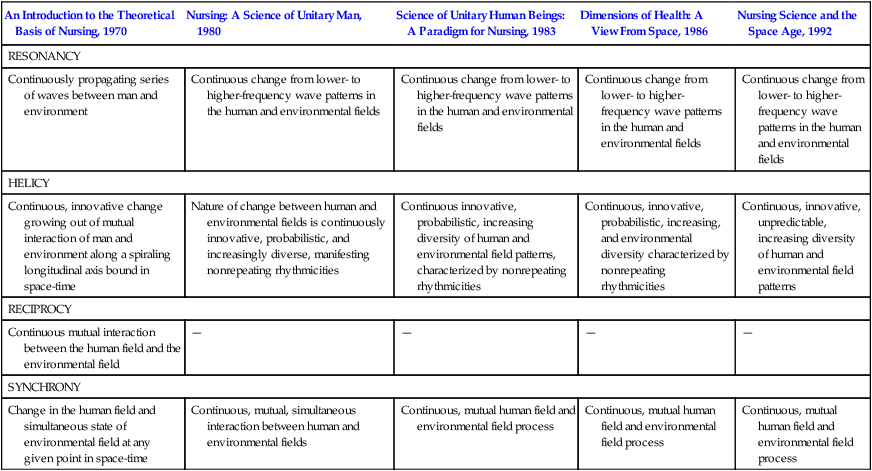

“Professional practice in nursing seeks to promote symphonic interaction between man and environment, to strengthen the coherence and integrity of the human field, and to direct and redirect patterning of the human and environmental fields for realization of maximum health potential” (Rogers, 1970, p. 122). In 1988, colleagues and students joined her in forming the Society of Rogerian Scholars (SRS) and immediately began to publish Rogerian Nursing Science News, a members’ newsletter, to disseminate theory developments and research studies (Malinski & Barrett, 1994). In 1993, SRS began to publish a refereed journal, Visions: The Journal of Rogerian Nursing Science. The society includes a foundation that maintains and administers the Martha E. Rogers Fund. To keep pace with the Society of Rogerian Scholars, see www.societyofregerianscholars.org/biography_mer.html. In 1995, New York University established the Martha E. Rogers Center to provide a structure for continuation of Rogerian research and practice. A verbal portrait of Rogers includes such descriptive terms as stimulating, challenging, controversial, idealistic, visionary, prophetic, philosophical, academic, outspoken, humorous, blunt, and ethical. Rogers remains a widely recognized scholar honored for her contributions and leadership in nursing. Butcher (1999) noted, “Rogers, like Nightingale, was extremely independent, a determined, perfectionist individual who trusted her vision despite skepticism” (p. 114). Colleagues consider her one of the most original thinkers in nursing as she synthesized and resynthesized knowledge into “an entirely new system of thought” (Butcher, 1999, p. 111). Today she is thought of as “ahead of her time, in and out of this world” (Ireland, 2000, p. 59). Rogers’ grounding in the liberal arts and sciences is apparent in both the origin and the development of her conceptual model, published in 1970 as An Introduction to the Theoretical Basis of Nursing (Rogers, 1970). Aware of the interrelatedness of knowledge, Rogers credited scientists from multiple disciplines with influencing the development of the Science of Unitary Human Beings. Rogerian science emerged from the knowledge bases of anthropology, psychology, sociology, astronomy, religion, philosophy, history, biology, physics, mathematics, and literature to create a model of unitary human beings and the environment as energy fields integral to the life process. Within nursing, the origins of Rogerian science can be traced to Nightingale’s proposals and statistical data, placing the human being within the framework of the natural world. This “foundation for the scope of modern nursing” began nursing’s investigation of the relationship between human beings and the environment (Rogers, 1970, p. 30). Newman (1997) describes the Science of Unitary Human Beings as “the study of the moving, intuitive experience of nurses in mutual process with those they serve” (p. 9). Evident in her model are the influence of Einstein’s (1961) theory of relativity in relation to space-time and Burr and Northrop’s (1935) electrodynamic theory relating to electrical fields. By the time von Bertalanffy (1960) introduced general system theory, theories regarding a universe of open systems were beginning to affect the development of knowledge within all disciplines. With general system theory, the term negentropy was brought into use to signify increasing order, complexity, and heterogeneity in direct contrast to the previously held belief that the universe was winding down. Rogers, however, refined and purified general system theory by denying hierarchical subsystems, the concept of single causation, and the predictability of a system’s behavior through investigations of its parts. Introducing quantum theory and the theories of relativity and of probability fundamentally challenged the prevailing absolutism. As new knowledge escalated, the traditional meanings of homeostasis, steady state, adaptation, and equilibrium were questioned seriously. The closed-system, entropic model of the universe was no longer adequate to explain phenomena, and evidence accumulated in support of a universe of open systems (Rogers, 1994b). Continuing development within other disciplines of the acausal, nonlinear dynamics of life validated Rogers’ model. Most notable of this development is that of chaos theory, quantum physics’ contribution to the science of complexity (or wholeness), that blurs the boundaries between the disciplines, allowing exploration and deepening of the understanding of the totality of human experience. Nursing is a learned profession and is both a science and an art. It is an empirical science and, like other sciences, that lies in the phenomenon central to its focus. Rogerian nursing focuses on concern with people and the world in which they live—a natural fit for nursing care, as it encompasses people and their environments. The integrality of people and their environments, operating from a pandimensional universe of open systems, points to a new paradigm and initiates the identity of nursing as a science. The purpose of nursing is to promote health and well-being for all persons. The art of nursing is the creative use of the science of nursing for human betterment (Rogers, 1994b). “Professional practice in nursing seeks to promote symphonic interaction between human and environmental fields, to strengthen the integrity of the human field, and to direct and redirect patterning of the human and environmental fields for realization of maximum health potential” (Rogers, 1970, p. 122). Nursing exists for the care of people and the life process of humans. Rogers defines person as an open system in continuous process with the open system that is the environment (integrality). She defines unitary human being as an “irreducible, indivisible, pandimensional energy field identified by pattern and manifesting characteristics that are specific to the whole” (Rogers, 1992, p. 29). Human beings “are not disembodied entities, nor are they mechanical aggregates.…Man is a unified whole possessing his own integrity and manifesting characteristics that are more than and different from the sum of his parts” (Rogers, 1970, pp. 46-47). Within a conceptual model specific to nursing’s concern, people and their environment are perceived as irreducible energy fields integral with one another and continuously creative in their evolution. Rogers uses health in many of her earlier writings without clearly defining the term. She uses the term passive health to symbolize wellness and the absence of disease and major illness (Rogers, 1970). Her promotion of positive health connotes direction in helping people with opportunities for rhythmic consistency (Rogers, 1970). Later, she wrote that wellness “is a much better term…because the term health is very ambiguous” (Rogers, 1994b, p. 34). Rogers uses health as a value term defined by the culture or the individual. Health and illness are manifestations of pattern and are considered “to denote behaviors that are of high value and low value” (Rogers, 1980). Events manifested in the life process indicate the extent to which a human being achieves maximum health according to some value system. In Rogerian science, the phenomenon central to nursing’s conceptual system is the human life process. The life process has its own dynamic and creative unity, inseparable from the environment, and is characterized by the whole (Rogers, 1970). In “Dimensions of Health: A View from Space,” Rogers (1986b) reaffirms the original theoretical assertions, adding philosophical challenges to the prevailing perception of health. Stressing a new worldview that focuses on people and their environment, she lists iatrogenesis, nosocomial conditions, and hypochrondriasis as the major health problems in the United States. Rogers (1986b) writes, “A new world view compatible with the most progressive knowledge available is a necessary prelude to studying human health and to determining modalities for its promotion whether on this planet or in the outer reaches of space” (p. 2). Rogers (1994a) defines environment as “an irreducible, pandimensional energy field identified by pattern and manifesting characteristics different from those of the parts. Each environmental field is specific to its given human field. Both change continuously and creatively” (p. 2). Environmental fields are infinite, and change is continuously innovative, unpredictable, and characterized by increasing diversity. Environmental and human fields are identified by wave patterns manifesting continuous mutual change. The principles of homeodynamics postulate a way of perceiving unitary human beings. The evolution of these principles from 1970 to 1994 is depicted in Table 13-1. Rogers (1970) wrote, “The life process is homeodynamic.…These principles postulate the way the life process is and predict the nature of its evolving” (p. 96). Rogers identified the principles of change as helicy, resonancy, and integrality. The helicy principle describes spiral development in continuous, nonrepeating, and innovative patterning. Rogers’ articulation of the principle of helicy describing the nature of change evolved from probabilistic to unpredictable, while remaining continuous and innovative. According to the principle of resonancy, patterning changes with development from lower to higher frequency, that is, with varying degrees of intensity. Resonancy embodies wave frequency and energy field pattern evolution. Integrality, the third principle of homeodynamics, stresses the continuous mutual process of person and environment. The principles of homeodynamics evolved into a concise and clear description of the nature, process, and context of change within human and environmental energy fields (Hills & Hanchett, 2001). Table 13-1 Evolution of Principles of Homeodynamics: 1970, 1983, 1986, and 1992 Conceptualized by Joann Daily from the following sources: Riehl, J. P., & Roy, C. (Eds.). (1980). Conceptual models for nursing practice (2nd ed.). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. Rogers, M. E. (1970). An introduction to the theoretical basis of nursing. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. Rogers, M. E. (1983). Science of unitary human beings: A paradigm for nursing. In I. W. Clements & F. B. Roberts (Eds.), Family health: A theoretical approach to nursing care. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Table revised by Denise Schnell and Therese Wallace in 1988 to include the following source: Rogers, M. E. (1986b). Dimensions of health: A view from space (obtained through personal correspondence with Martha Rogers, March 1988). Table updated by Cathy Murray from the following source: Rogers, M. E. (1992). Nursing science and the space age. Nursing Science Quarterly, 5(1), 27-34. 1. “Man is a unified whole possessing his own integrity and manifesting characteristics more than and different from the sum of his parts” (energy field) (p. 47). 2. “Man and environment are continuously exchanging matter and energy with one another” (openness) (p. 54). 3. “The life process evolves irreversibly and unidirectionally along the space-time continuum” (helicy) (p. 59). 4. “Pattern and organization identify man and reflect his innovative wholeness” (pattern and organization) (p. 65). 5. “Man is characterized by the capacity for abstraction and imagery, language and thought, sensation, and emotion” (sentient, thinking being) (p. 73). Historically, nursing has equated practice with the practical and theory with the impractical. More appropriately, theory and practice are two related components in a unified nursing practice. Alligood (1994) articulates how theory and practice direct and guide each other as they expand and increase unitary nursing knowledge. Nursing knowledge provides the framework for the emergent artistic application of nursing care (Rogers, 1970). Within Rogers’ model, the critical thinking process directing practice can be divided into three components: pattern appraisal, mutual patterning, and evaluation. Cowling (2000) states that pattern appraisal is meant to avoid, if not transcend, reductionistic categories of physical, mental, spiritual, emotional, cultural, and social assessment frameworks. Through observation and participation, the nurse focuses on human expressions of reflection, experience, and perception to form a profile of the patient. Mutual exploration of emergent patterns allows identification of unitary themes predominant in the pandimensional human-environmental field process. Mutual understanding implies knowing participation but does not lead to the nurse’s prescribing change or predicting outcomes. As Cowling (2000) explains, “A critical feature of the unitary pattern appreciation process, and also of healing through appreciating wholeness, is a willingness on the part of the scientist or practitioner to let go of expectations about change” (p. 31). Evaluation centers on the perceptions emerging during mutual patterning. Noninvasive patterning modalities used within Rogerian practice include, but are not limited to, acupuncture, aromatherapy, therapeutic touch, massage, guided imagery, meditation, self-reflection, guided reminiscence, journal keeping, humor, hypnosis, sleep, hygiene, dietary manipulation, music, and physical exercise (Alligood, 1991a; Bultemeier, 1997; Kim, Park, & Kim, 2008; Larkin, 2007; Levin, 2006; Lewandowski, et al., 2005; MacNeil, 2006; Siedliecki & Good, 2006; Smith, Kemp, Hemphill, & Vojir, 2002; Smith & Kyle, 2008; Walling, 2006). Barrett (1998) notes that integral to these modalities are “meaningful dialogue, centering, and pandimensional authenticity (genuineness, trustworthiness, acceptance, and knowledgeable caring)” (p. 138). Nurses participate in the lived experience of health in a multitude of roles, including “facilitators and educators, advocates, assessors, planners, coordinators, and collaborators,” by accepting diversity, recognizing patterns, viewing change as positive, and accepting the connectedness of life (Malinski, 1986, p. 27) These roles may require the nurse to “let go of traditional ideas of time, space, and outcome” (Malinski, 1997, p. 115). The Rogerian model provides a challenging and innovative framework from which to plan and implement nursing practice, which Barrett (1998) defines as the “continuous process (of voluntary mutual patterning) whereby the nurse assists clients to freely choose with awareness ways to participate in their well-being” (p. 136). Rogers clearly articulated guidelines for the education of nurses within the Science of Unitary Human Beings. Rogers discusses structuring nursing education programs to teach nursing as a science and as a learned profession. Barrett (1990b) calls Rogers a “consistent voice crying out against antieducation-alism and dependency” (p. 306). Rogers’ model clearly articulates values and beliefs about human beings, health, nursing, and the educational process. As such, it has been used to guide curriculum development in all levels of nursing education (Barrett, 1990b; DeSimone, 2006; Hellwig & Ferrante, 1993; Mathwig, Young, & Pepper, 1990). Rogers (1990) stated that nurses must commit to lifelong learning and noted, “The nature of the practice of nursing (is) the use of knowledge for human betterment” (p. 111). Rogers advocated separate licensure for nurses prepared with an associate’s degree and those with a baccalaureate degree, recognizing that there is a difference between the technically oriented and the professional nurse. In her view, the professional nurse must be well rounded and educated in the humanities, sciences, and nursing. Such a program would include a basic education in language, mathematics, logic, philosophy, psychology, sociology, music, art, biology, microbiology, physics, and chemistry; elective courses could include economics, ethics, political science, anthropology, and computer science (Barrett, 1990b). With regard to the research component of the curriculum, Rogers (1994b) stated the following: Undergraduate students need to be able to identify problems, to have tools of investigation and to do studies that will allow them to use knowledge for the improvement of practice, and they should be able to read the literature intelligently. People with master’s degrees ought to be able to do applied research.…The theoretical research, the fundamental basic research is going to come out of doctoral programs of stature that focus on nursing as a learned field of endeavor (p. 34). Barrett (1990b) notes that with increasing use of technology and increasing severity of illness of hospitalized patients, students may be limited to observational experiences in these institutions. Therefore, the acquisition of manipulative technical skills must be accomplished in practice laboratories and at alternative sites, such as clinics and home health agencies. Other sites for education include health promotion programs, managed care programs, homeless shelters, and senior centers. Rogers’ conceptual model provides a stimulus and direction for research and theory development in nursing science. Fawcett (2000), who insists that the level of abstraction affects direct empirical observation and testing, endorses the designation of the Science of Unitary Human Beings as a conceptual model rather than a grand theory. She states clearly that the purpose of the work determines its category. Conceptual models “identify the purpose and scope of nursing and provide frameworks for objective records of the effects of nursing” (Fawcett, 2005, p. 18). Emerging from Rogers’ model are theories that explain human phenomena and direct nursing practice. The Rogerian model, with its implicit assumptions, provides broad principles that conceptually direct theory development. The conceptual model provides a stimulus and direction for scientific activity. Relationships among identified phenomena generate both grand (further development of one aspect of the model) and middle range (description, explanation, or prediction of concrete aspects) theories (Fawcett, 1995). Two prominent grand nursing theories grounded in Rogers’ model are Newman’s health as expanding consciousness and Parse’s human becoming (Fawcett, 2005). Numerous middle range theories have emerged from Rogers’ three homeodynamic principles as follows: (1) helicy, (2) resonancy, and (3) integrality (Figure 13-1). Exemplars of middle range theories derived from homeodynamic principles include power-as-knowing-participationin-change (helicy) (Barrett, 1990a), the theory of perceived dissonance (resonancy) (Bultemeier, 1997), and the theory of interactive rhythms (integrality) (Floyd, 1983). In her overview of Rogerian science–based theories, Malinski (2006) identifies work within specific concepts: (1) self-transcendence (Reed, 1991, 2003), enlightenment (Hills & Hanchett, 2001), and spirituality (Malinski, 1994; Smith, 1994); (2) turbulence (Butcher, 1993) and dissonance (Bultemeier, 1997); (3) aging (Alligood & McGuire, 2000; Butcher, 2003); (4) intentionality (Zahourek, 2005); and (5) caring (Smith, 1999). Other middle range theories encompass the phenomena of human field motion (Ference, 1986), as well as creativity, actualization, and empathy (Alligood, 1991b). Rogers (1986a) maintains that research in nursing must examine unitary human beings as integral with their environment. Therefore, the intent of nursing research is to examine and understand a phenomenon and, from this understanding, design patterning activities that promote healing. To obtain a clearer understanding of lived experiences, the person’s perception and sentient awareness of what is occurring are imperative. The variety of events associated with human phenomena provides the experiential data for research that is directed toward capturing the dynamic, ever-changing life experiences of human beings. Selecting the correct method for examining the person and the environment as health-related phenomena is the challenge of the Rogerian researcher. Both quantitative and qualitative approaches have been used in the Science of Unitary Human Beings research, although not all researchers agree that both are appropriate. Researchers do agree that ontological and epistemological congruence between the model and the approach must be considered and reflected by the research question (Barrett, Cowling, Carboni, & Butcher, 1997). Quantitative experimental and quasi-experimental designs are not appropriate, because their purpose is to reveal causal relationships. Descriptive, explanatory, and correlational designs are more appropriate, because they recognize “the unitary nature of the phenomenon of interest” and may “propose evidence of patterned mutual change among variables” (Sherman, 1997, p. 132). Specific research methods emerging from middle range theories based on the Rogerian model capture the human-environmental phenomena. As a means of capturing the unitary human being, Cowling (1998) describes the process of pattern appreciation using the combined research and practice case study method. Case study attends to the whole person (irreducibility), aims at comprehending the essence (pattern), and respects the inherent interconnectedness of phenomena. A pattern profile is composed through a synopsis and synthesis of the data (Barrett, et al., 1997). Other innovative methods of recording and entering the human-environmental field phenomenon include photo-disclosure (Bultemeier, 1997), hermeneutic text interpretation (Alligood, 2002; Alligood & Fawcett, 1999), and measurement of the effect of dialogue combined with noninvasive modalities (Leddy & Fawcett, 1997). Rogerian instrument development is extensive and ever-evolving. A wide range of instruments for measuring human-environmental field phenomena have emerged (Table 13-2). The continual emergence of middle range theories, research approaches, and instruments demonstrates recognition of the importance of Rogerian science to nursing. Table 13-2 Research Instruments and Practice Tools Derived From the Science of Unitary Human Beings From Fawcett, J. (2005). Contemporary nursing knowledge: Analysis and evaluation of nursing models and theories (pp. 337-339). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. Used with permission. F. A. Davis

Unitary Human Beings

CREDENTIALS AND BACKGROUND OF THE THEORIST

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

MAJOR ASSUMPTIONS

Nursing

Person

Health

Environment

THEORETICAL ASSERTIONS

An Introduction to the Theoretical Basis of Nursing, 1970

Nursing: A Science of Unitary Man, 1980

Science of Unitary Human Beings: A Paradigm for Nursing, 1983

Dimensions of Health: A View From Space, 1986

Nursing Science and the Space Age, 1992

RESONANCY

Continuously propagating series of waves between man and environment

Continuous change from lower- to higher-frequency wave patterns in the human and environmental fields

Continuous change from lower- to higher-frequency wave patterns in the human and environmental fields

Continuous change from lower- to higher-frequency wave patterns in the human and environmental fields

Continuous change from lower- to higher-frequency wave patterns in the human and environmental fields

HELICY

Continuous, innovative change growing out of mutual interaction of man and environment along a spiraling longitudinal axis bound in space-time

Nature of change between human and environmental fields is continuously innovative, probabilistic, and increasingly diverse, manifesting nonrepeating rhythmicities

Continuous innovative, probabilistic, increasing diversity of human and environmental field patterns, characterized by nonrepeating rhythmicities

Continuous, innovative, probabilistic, increasing, and environmental diversity characterized by nonrepeating rhythmicities

Continuous, innovative, unpredictable, increasing diversity of human and environmental field patterns

RECIPROCY

Continuous mutual interaction between the human field and the environmental field

—

—

—

—

SYNCHRONY

Change in the human field and simultaneous state of environmental field at any given point in space-time

Continuous, mutual, simultaneous interaction between human and environmental fields

Continuous, mutual human field and environmental field process

Continuous, mutual human field and environmental field process

Continuous, mutual human field and environmental field process

ACCEPTANCE BY THE NURSING COMMUNITY

Practice

Education

Research

Human Field Motion Test (HFMT) (Ference, 1980, 1986; Young et al., 2001)

Measures human field motion by means of semantic differential ratings of the concepts My Motor Is Running and My Field Expansion.

Perceived Field Motion Scale (PFM) (Yarcheski & Mahon, 1991; Young et al., 2001)

Measures the perceived experience of motion by means of semantic differential ratings of the concept My Field Motion.

Human Field Rhythms (HFR) (Yarcheski & Mahon, 1991; Young et al., 2001)

Measures the frequency of rhythms in the human-environmental energy field mutual process by means of a one-item visual analogue scale.

Index of Field Energy (IFE) (Gueldner, as cited in Watson et al., 1997; Young et al., 2001)

Measures human field dynamics by means of semantic differential ratings of 18 pairs of simple black-and-white line drawings.

The Well-being Picture Scale (Gueldner et al., 2005)

Revision of the Index of Field Energy. A 10-item non–language-based pictorial scale that measures general well-being.

Power as Knowing Participation in Change Tool (PKPCT) (Barrett, 1984, 1986, 1990a; Watson et al., 1997; Young et al., 2001)

Measures the person’s capacity to participate knowingly in change by means of semantic differential ratings of the concepts Awareness, Choices, Freedom to Act Intentionally, and Involvement in Creating Changes.

Diversity of Human Field Pattern Scale (DHFPS) (Hastings-Tolsma, 1993; Watson et al., 1997; Young et al., 2001)

Measures diversity of human field pattern, or degree of change in the evolution of human potential throughout the life process, by means of Likert scale ratings of 16 items.

Human Field Image Metaphor Scale (HFIMS) (Johnston, 1993a, 1993b, 1994; Young et al., 2001)

Measures the individual’s awareness of the infinite wholeness of the human field by means of Likert scale ratings of 14 metaphors that represent perceived potential and 11 metaphors that represent perceived field integrality.

Temporal Experience Scale (TES) (Paletta, 1988, 1990; Young et al., 2001)

Measures subjective experience of temporal awareness by means of Likert scale ratings of 24 metaphors representing the factors of time dragging, time racing, and timelessness.

Assessment of Dream Experience (ADE) (Watson, 1994, 1999; Watson et al., 1997; Young et al., 2001)

Measures dreaming as a beyond waking experience by means of Likert scale ratings of the extent to which 20 items describe what the individual’s dreams have been like during the past 2 weeks.

Person-Environment Participation Scale (PEPS) (Leddy, 1995, 1999; Young et al., 2001)

Measures the person’s experience of continuous human-environment mutual process by means of semantic differential ratings of 15 bipolar adjectives representing the content areas of comfort, influence, continuity, ease, and energy.

Leddy Heartiness Scale (LHS) (Leddy, 1996; Young et al., 2001)

Measures the person’s perceived purpose and power to achieve goals by means of Likert scale ratings of 26 items representing meaningfulness, ends, choice, challenge, confidence, control, capability to function, and connections.

McCanse Readiness for Death Instrument (MRDI) (McCanse, 1988; 1995)

Measures physiological, psychological, sociological, and spiritual aspects of healthy field pattern, as death is developmentally approached by means of a 26-item structured interview questionnaire.

Mutual Exploration of the Healing Human-Environmental Field Relationship (Carboni, 1992; Young et al., 2001)

Measures nurses’ and clients’ experiences and expressions of changing configurations of energy field patterns of the healing human-environmental field relationship using semi-structured and open-ended items. Forms for a nurse and a single client and for a nurse and two or more clients are available.

Practice Tool and Citation

Description

Nursing Process Format (Falco & Lobo, 1995)

Guides use of a Rogerian nursing process, including nursing assessment, nursing diagnosis, nursing planning for implementation, and nursing evaluation, according to the homeodynamic principles of integrality, resonancy, and helicy.

Assessment Tool (Smith et al., 1991)

Guides use of a Rogerian nursing process, including assessment, diagnosis, implementation, and evaluation, according to the homeodynamic principles of complementarity (i.e., integrality), resonancy, and helicy, for patients hospitalized in a critical care unit and their family members, using open-ended questions.

Critical Thinking for Pattern Appraisal, Mutual Patterning, and Evaluation Tool (Bultemeier, 2002)

Provides guidance for the nurse’s application of pattern appraisal, mutual patterning, and evaluation, as well as areas for the client’s self-reflection, patterning activities, and personal appraisal.

Nursing Assessment of Patterns Indicative of Health (Madrid & Winstead-Fry, 1986)

Guides assessment of patterns, including relative present, communication, sense of rhythm, connection to environment, personal myth, and system integrity.

Assessment Tool for Postpartum Mothers (Tettero et al., 1993)

Guides assessment of mothers experiencing the challenges of their first child during the postpartum period.

Assessment Criteria for Nursing Evaluation of the Older Adult (Decker, 1989)

Guides assessment of the functional status of older adults living in their own homes, including demographic data, client prioritization of problems, sequential patterning (e.g., family of origin culture, past illnesses), rhythmical patterning (e.g., healthcare usage, medication usage, social contacts, acute illnesses), and cross-sectional patterning (e.g., current living arrangements and health concerns, cognitive and emotional status).

Holistic Assessment of the Chronic Pain Client (Garon, 1991)

Guides holistic assessment of clients living in their own homes and experiencing chronic pain, including the environmental field, the community, and all systems in contact with the client; the home environment; client needs and expectations; client and family strengths; the client’s pain experience—location, intensity, cause, meaning, effects on activities, life, and relationships, relief measures, and goals; and client and family feelings about illness and pain.

Human Energy Field Assessment Form (Wright, 1989, 1991)

Used to record findings related to human energy field assessment as practiced in therapeutic touch, including location of field disturbance on a body diagram and strength of the overall field and intensity of the field disturbance on visual analogue scales.

Family Assessment Tool (Whall, 1981)

Guides assessment of families in terms of individual subsystem considerations, interactional patterns, unique characteristics of the whole family system, and environmental interface synchrony.

An Assessment Guideline for Work with Families (Johnston, 1986)

Guides assessment of the family unit, in terms of definition of family, family organization, belief system, family developmental needs, economic factors, family field and environmental field complementarity, communication patterns, and supplemental data, including health assessment of individual family members, developmental factors, member interactions, and relationships.

Nursing Process Format for Families (Reed, 1986)

Guides the use of a developmentally oriented nursing process for families.

A Conceptual Tool Kit for Community Health Assessment (Hanchett, 1979)

Tools used to guide assessment of the energy, individuality, and pattern and organization of a community.

Community Health Assessment (Hanchett, 1988)

Guides assessment of a community in areas of diversity; rhythms, including frequencies of colors, rhythms of light, and patterns of sound; motion; experience of time; pragmatic-imaginative-visionary worldviews; and sleep-wake beyond waking rhythms.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Unitary Human Beings

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access