CHAPTER TWO Understanding human behaviour and group dynamics

INTRODUCTION

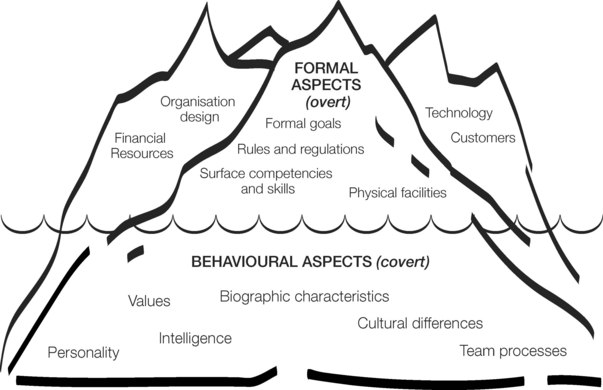

Hellriegal et al. (1998) envision an organisation as an iceberg in order to understand why people behave as they do at work. What sinks ships is not always what sailors can see, but what they cannot see (see Figure 2.1). The overt, formal aspects are really only the tip of the iceberg. It is just as important to concentrate on what you cannot see—the covert, behavioural aspects. These covert behaviours will form the focus of this chapter.

THEORIES OF HUMAN BEHAVIOUR

As indicated in Chapter 1, understanding the make-up of people is important for all who lead others. Since management is sometimes seen as ‘getting things done through other people’, understanding people is a prerequisite to operating effectively as a manager. Being aware of our own strengths and weaknesses and those of others, and knowing how to develop or use this knowledge is helpful not only in organisations but also in our personal interactions with others.

Lansbury and Spillane (1983) summarise theories of human behaviour into three broad perspectives: psychoanalytical theory, environmental theory and social learning theory.

Psychoanalytical theory

Psychoanalytical theory is based on the work of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, and emphasises unconscious motives as a component of personality (Mullins 1999). Psychoanalytical theory proposes that internal processes of the psyche determine human behaviour. Our behaviours are considered to be an interplay between conscious and unconscious desires (Lansbury & Spillane 1983). The prescription for mental health, according to psychoanalysts, is self-insight. Understanding the processes of the psyche, including those that we like and do not like, is the basis of much therapy today.

Environmental theory

Environmental theory is primarily concerned with reinforcement, imitation and socialisation. This theory contends that a person’s development is influenced by their own experiences. Environmental theorists argue that it is stimuli from our environment that generates behavioural responses (Steers 1989). Fashion trends and the influences of peer group pressure on behaviour support environmental theory. Environmental theory has been the basis for understanding how certain aspects of reward and punishment influence human behaviour. A number of popular management schemes of today, for example, reward and bonus incentives, are based on environmental theory.

Even though environmental theory predicts simple human behaviour over short periods and in a structured situation, such as when people are being closely supervised, critics (Chomsky 1959; Locke 1966) believe human behaviour to be more complex, and propose that environmental theory does not account for creative activities, such as the capacity to generate new ideas or paint a picture. There are also employees who do not appear to be influenced by offers of reward or threats of punishment.

Social learning theory

Social learning theory suggests that behaviour is the outcome of an interaction between the environmental stimulus and the personality make-up of the individual (Bandura 1986). Social learning theory asserts that both the environment and personal characteristics such as personality, national culture and intelligence, influence a person’s behaviour. The theory is well documented by Bandura (1986), who emphasises the importance of learning from other people and person–situation interaction.

Social learning theory provides a basis for understanding the complex interaction between psychological and environmental factors that culminate in human behaviour. For example, it explains how the impact of certain environments upon a person’s behaviour depends upon their values and goals (Bandura 1986). Social learning theory has proven to be effective in predicting what people will do and how long they will persist in the face of setbacks. For managers, it can be a useful tool for influencing others in a desired direction.

FACTORS INFLUENCING INDIVIDUAL PERFORMANCE

The amazing feature of humans is their diversity. What is work for one person is pleasure for another (for example, gardening!). What motivates one worker will demotivate another. Vecchio et al. (1992) propose a simple formula for increased performance—they suggest that people perform better when they work at a job they want to do. It seems so logical doesn’t it? But it is more difficult than it sounds. Not only do we need to consider individual work preferences, but many other factors can affect our performance and sense of wellbeing in employment.

Let us consider the individual performance equation proposed by Wood et al. (2001, p.91) that captures these ideas:

Individual attributes

Competency characteristics

An individual’s level of competency and a person’s work ability are highly dependent upon his or her intelligence (Behling 1998). Gardener (1993) regarded the simplification of intelligence in terms of an IQ measure as unrealistic in light of different intelligent behaviour that could be observed in everyday life. Although intelligence tests may offer one explanation of why an individual performs better in an academic institution, and may be a legitimate measure of such behaviour, Gardener (1993) states that they fail to take account of the full range of intelligent activity. He suggests that there are multiple intelligences (see Table 2.1) and categorises them into seven varieties (all of which can be divided further).

Table 2.1 Types of intelligence

| Verbal intelligence | Ability to understand the meaning of words and comprehend readily what is read or heard |

| Mathematical intelligence | To be speedy and accurate in arithmetic computations such as adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing |

| Spatial capacity | Ability shown by artists and architects |

| Kinaesthetic intelligence | Abilities of a physical nature |

| Musical intelligence | Abilities shown by musicians |

| Personal intelligence—interpersonal skills | Skills for dealing with other people |

| Personal intelligence—intrapersonal skills | Knowing oneself |

Standard IQ tests only examine the first two types, verbal and mathematical intelligence (Behling 1998). Gardener calls personal intelligence (which is comprised of interpersonal and intrapersonal skills) emotional intelligence, or EQ. Leaders need to appreciate that a major influencing factor affecting work performance is the ability of the employee (Goleman 1996, p.34). Ensuring that the right people are selected for work and have an appropriate level of intelligence (IQ and EQ) is a critical human resource management process, now assisted by the appropriate use of psychological tests (see Dakin et al. 1994).

Personality characteristics

These can be defined as the traits that reflect what the person is like and which can influence behaviour in certain predictable ways (Stemberg & Kaufman 1998). Knowledge of personality can help managers understand, predict and even influence the behaviour of other people.

Four dimensions of personality that have special relevance in work settings include problem-solving style, Type A–Type B behaviour, locus of control and Machiavellianism. The latter two concepts are considered in detail in Chapter 3, and should be read in conjunction with this chapter. They will therefore not be addressed in the following material.

Evaluation involves making judgements about how to deal with information once it has been collected (Stemberg & Kaufman 1998). Styles of information evaluation vary from an emphasis on feeling to an emphasis on thinking. Stemberg and Kaufman (1998) describe feeling-type individuals as being oriented towards conformity and being willing to accommodate other people. They try to avoid problems that might result in disagreements. Thinking-type people use reason to deal with problems. They downplay emotional aspects in the problem situation.

Individuals with Type A personalities tend to work fast on task performance and in interpersonal relations they tend to be impatient, uncomfortable, irritable and aggressive. Such tendencies indicate ‘obsessive’ behaviour, however, Type A personalities are fairly widespread among many managers (Stemberg & Kaufman 1998). These are hard-driving, detail-oriented people who have high performance standards and thrive on routine. But when such work obsessions are carried to the extreme, resistance to change, over-control of subordinates and difficulties in interpersonal relationships result. People with Type A personalities create a lot of stress for themselves in situations that Type Bs find relatively stress-free (Stemberg & Kaufman 1998). Type B behaviour is a profile of someone more easygoing and less competitive in relation to daily life events. Type Bs are more casual about appointments and do not feel rushed like Type A personalities. Hence they may not see the urgency in tasks and deadlines. They do things more slowly and tend to express their feelings more openly than Type A, who hold on to their feelings.

Values

Rokeach (1973) describes values as beliefs that guide actions and judgements across a variety of situations. Parents, friends, teachers and external reference groups can all influence individual values. A person’s values develop as a product of learning and experience in the cultural setting in which he or she lives. As learning and experiences vary from one person to the next, value differences are the inevitable result. Consider the values people place on family, religion and personal possessions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree