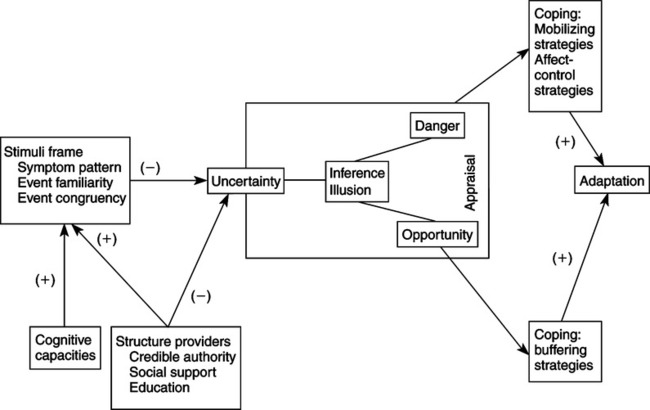

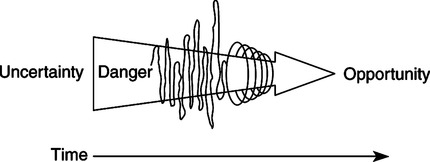

Donald E. Bailey, Jr. and Janet L. Stewart 1. A community version (MUIS-C) for chronically ill individuals who are not hospitalized or receiving active medical care 2. A measure of parents’ perceptions of uncertainty (PPUS) with regard to their child’s illness experience 3. A measure of uncertainty in spouses or other family members when another member of the family is acutely ill (PPUS-FM) When Mishel began her research into uncertainty, the concept had not previously been applied in the health and illness context. Her original Uncertainty in Illness Theory (Mishel, 1988) drew from existing information-processing models (Warburton, 1979) and personality research (Budner, 1962) from the psychology discipline, which characterized uncertainty as a cognitive state resulting from insufficient cues with which to form a cognitive schema or internal representation of a situation or event. Mishel attributes the underlying stress-appraisal-copingadaptation framework in the original theory to the work of Lazarus and Folkman (1984). The unique aspect was her application of this framework to uncertainty as a stressor in the context of illness, which made the framework particularly meaningful for nursing. With the reconceptualization of the theory, Mishel (1990) recognized that the Western approach to science supported a mechanistic view in its emphasis on control and predictability. By using critical social theory, Mishel recognized the bias inherent in the original theory, an orientation toward certainty and adaptation. Mishel then incorporated tenets from chaos theory, and because of its focus on open systems, allowed for a more accurate representation of how chronic illness creates disequilibrium and how people ultimately can incorporate continual uncertainty to find new meaning in illness. The Uncertainty in Illness Theory grew out of Mishel’s dissertation research with hospitalized patients, for which she used both qualitative and quantitative findings to generate the first conceptualization of uncertainty in the context of illness. Beginning with the publication of Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Scale (Mishel, 1981), there has been extensive research into adults’ experiences with uncertainty related to chronic and life-threatening illnesses. Considerable empirical evidence has accumulated to support Mishel’s theoretical model in adults. Several recent integrative reviews of uncertainty research have comprehensively summarized and critiqued the current state of the science (Mast, 1995; Mishel, 1997a, 1999; Stewart & Mishel, 2000). The authors include studies here that directly support the elements of Mishel’s uncertainty model. Most empirical studies have focused predominantly on two of the antecedents of uncertainty, stimuli frame and structure providers, and the relationship between uncertainty and psychological outcomes. Mishel tested other elements of the model, such as the mediating roles of appraisal and coping, early in her program of research (Mishel & Braden, 1987; Mishel, Padilla, Grant, & Sorenson, 1991; Mishel & Sorenson, 1991), but these model elements, along with cognitive capacity as an antecedent to uncertainty, have generated less research attention. Several studies have shown that objective or subjective indicators of the severity of life-threat or illness symptoms were associated positively with uncertainty (Braden, 1990; Grootenhuis & Last, 1997; Hinds, Birenbaum, Clarke-Steffen, Quargnenti, Kreissman, Kazak, et al., 1996; Janson-Bjerklie, Ferketich, & Benner, 1993; Tomlinson, Kirschbaum, Harbaugh, & Anderson, 1996). Across a sustained illness trajectory, unpredictability in symptom onset, duration, and intensity has been related to perceived uncertainty (Becker, Jason-Bjerklie, Benner, Slobin, & Ferketich, 1993; Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Jessop & Stein, 1985; Mishel & Braden, 1988; Murray, 1993). Similarly, the ambiguous nature of illness symptoms and the consequent difficulty in determining the significance of physical sensations frequently have been identified as sources of uncertainty (Cohen, 1993; Comaroff & Maguire, 1981; Hilton, 1988; Nelson, 1996; Weitz, 1989). Mishel and Braden (1988) found that social support had a direct impact on uncertainty by reducing perceived complexity and an indirect impact through its effect on the predictability of symptom pattern. The perception of stigma associated with some conditions, particularly HIV infection (Regan-Kubinski & Sharts-Hopko, 1995; Weitz, 1989) and Down’s syndrome (Van Riper & Selder, 1989), served to create uncertainty when families were unsure about how others would respond to the diagnosis. Family members have been shown consistently to experience high levels of uncertainty as well, which may further reduce the amount of support experienced by the patient (Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Hilton, 1996; Wineman, O’Brien, Nealon, & Kaskel, 1993). In addition, uncertainty was heightened by interactions with healthcare providers in which patients and family members received unclear information or simplistic explanations that did not fit their experience, or perceived that care providers were not expert or responsive enough to help them manage the intricacies of the illness (Becker et al., 1993; Comaroff & Maguire, 1981; Mason, 1985; Sharkey, 1995). Numerous studies have reported the negative impact of uncertainty on psychological outcomes, characterized variously as anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and psychological distress (Failla, Kuper, Nick, & Lee, 1996; Grootenhuis & Last, 1997; Jessop & Stein, 1985; Miles, Funk, & Kasper, 1992; Mishel & Sorenson, 1991; Schepp, 1991; Wineman, 1990). Uncertainty has also been shown to negatively impact quality of life (Braden, 1990; Padilla, Mishel, & Grant, 1992), satisfaction with family relationships (Wineman et al., 1993), satisfaction with healthcare services (Green & Murton, 1996; Turner, Tomlinson, & Harbaugh, 1990), and family caregivers’ maintenance of their own self-care activities (Brett & Davies, 1988; Lang, 1987; O’Brien, Wineman, & Nealon, 1995). Mishel reconceptualized the uncertainty theory in 1990 to accommodate responses to uncertainty over time in people with chronic conditions. The original theory was expanded to include the idea that uncertainty may not be resolved but may become part of an individual’s reality. In this context, uncertainty is reappraised as an opportunity and prompts the formation of a new, probabilistic view of life. To adopt this new view of life, the patient must be able to rely on social resources and healthcare providers who themselves accept the idea of probabilistic thinking (Mishel, 1990). If uncertainty can be framed as a normal part of life, it can become a positive force for multiple opportunities with resulting positive mood states (Gelatt, 1989; Mishel, 1990). Support for the reconceptualized Uncertainty in Illness Theory has been found in predominantly qualitative studies of people with a variety of chronic and life-threatening illnesses. The process of formulating a new view of life has been described by women with breast cancer and cardiac disease as a revised life perspective (Hilton, 1988), new life goals (Carter, 1993), new ways of being in the world (Mast, 1998; Nelson, 1996), growth through uncertainty (Pelusi, 1997), and new levels of self-organization (Fleury, Kimbrell, & Kruszewski, 1995). In studies of predominantly men with chronic illness or their caregivers, the process has been described as transformed self-identity and new goals for living (Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991), a more positive perspective on life (Katz, 1996), reevaluating what is worthwhile (Nyhlin, 1990), contemplation and self-appraisal (Charmaz, 1995), uncertainty viewed as opportunity (Baier, 1995), and redefining normal and building new dreams (Mishel & Murdaugh, 1987). Mishel’s original Uncertainty in Illness Theory, first published in 1988, included several major assumptions (Figure 28-1). The first two reflect how uncertainty was conceptualized originally within the psychology discipline’s information-processing models, as follows: 1. Uncertainty is a cognitive state, representing the inadequacy of an existing cognitive schema to support the interpretation of illness-related events. 2. Uncertainty is an inherently neutral experience, neither desirable nor aversive until it is appraised as such. 3. Adaptation represents the continuity of an individual’s usual biopsychosocial behavior and is the desired outcome of coping efforts to either reduce uncertainty appraised as danger or maintain uncertainty appraised as opportunity. 4. The relationships among illness events, uncertainty, appraisal, coping, and adaptation are linear and unidirectional, moving from situations promoting uncertainty toward adaptation. Ideally, under conditions of chronic uncertainty, a person gradually moves away from an evaluation of uncertainty as aversive to adopt a new view of life that accepts uncertainty as a part of reality (Figure 28-2). Thus uncertainty, especially in chronic or life-threatening illness, can result in a new level of organization and a new perspective on life, incorporating the growth and change that can result from uncertain experiences. Mishel asserted the following (1988, 1990): Several nurses have moved the theory from research to practice. Writing for an audience of critical care nurses, Hilton (1992) applied the theory in prescribing how to assess and intervene with patients experiencing uncertainty. Using examples of patients recovering from a cardiac event, Hilton explained how patients who misinterpret unclear physical symptoms may overprotect themselves by limiting physical activity that could be essential to their recovery. She further delineated how uncertainty can activate various types of coping to manage the situation, and described appropriate nursing interventions based on a thorough assessment of the patient’s or family member’s uncertainty. Wurzbach (1992), writing for medical-surgical nurses, exemplified the experience of a woman hospitalized with a lump in her breast. Focusing on the woman’s family history of breast cancer and no previous experience with hospitalization, Wurzbach counseled nurses to assess for certainty as well as uncertainty. Based on this assessment, management strategies in the form of nursing interventions were prescribed. Wurzbach cautioned nurses that intervention may not be appropriate in situations in which the patient experiences a moderate or optimal level of certainty-uncertainty. In these circumstances, patients may feel hopeful and may not require nursing intervention. Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Theory has also been applied to the practice of enterostomal therapy (ET) nursing. Righter (1995) described how trust in the ET nurse’s knowledge and experiences helps patients develop a cognitive schema for the ostomy experience. Functioning as a credible authority, an antecedent of uncertainty, an ET nurse is able to intervene with patients to promote effective coping strategies. Based on review of the database of the Managing Uncertainty in Illness Scale users (Mishel, 1997b), many are master’s prepared clinicians seeking to understand the experience of uncertainty in a variety of clinical settings with different patient populations. The scale and theory were both used by clinicians from eight countries other than the United States.

Uncertainty in Illness Theory

CREDENTIALS AND BACKGROUND OF THE THEORIST

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

MAJOR ASSUMPTIONS

People, as biopsychosocial systems, typically function in far-from-equilibrium states.

People, as biopsychosocial systems, typically function in far-from-equilibrium states.

Major fluctuations in a far-from-equilibrium system enhance the system’s receptivity to change.

Major fluctuations in a far-from-equilibrium system enhance the system’s receptivity to change.

Fluctuations result in repatterning, which is repeated at each level of the system.

Fluctuations result in repatterning, which is repeated at each level of the system.

THEORETICAL ASSERTIONS

Uncertainty occurs when a person cannot adequately structure or categorize an illness-related event because of the lack of sufficient cues.

Uncertainty occurs when a person cannot adequately structure or categorize an illness-related event because of the lack of sufficient cues.

Uncertainty can take the form of ambiguity, complexity, lack of or inconsistent information, or unpredictability.

Uncertainty can take the form of ambiguity, complexity, lack of or inconsistent information, or unpredictability.

As symptom pattern, event familiarity, and event congruence (stimuli frame) increase, uncertainty decreases.

As symptom pattern, event familiarity, and event congruence (stimuli frame) increase, uncertainty decreases.

Structure providers (credible authority, social support, and education) decrease uncertainty directly by promoting interpretation of events, and indirectly by strengthening the stimuli frame.

Structure providers (credible authority, social support, and education) decrease uncertainty directly by promoting interpretation of events, and indirectly by strengthening the stimuli frame.

Uncertainty appraised as danger prompts coping efforts directed at reducing the uncertainty and managing the emotional arousal generated by it.

Uncertainty appraised as danger prompts coping efforts directed at reducing the uncertainty and managing the emotional arousal generated by it.

Uncertainty appraised as opportunity prompts coping efforts directed at maintaining the uncertainty.

Uncertainty appraised as opportunity prompts coping efforts directed at maintaining the uncertainty.

The influence of uncertainty on psychological outcomes is mediated by the effectiveness of coping efforts to reduce uncertainty appraised as danger or to maintain uncertainty appraised as opportunity.

The influence of uncertainty on psychological outcomes is mediated by the effectiveness of coping efforts to reduce uncertainty appraised as danger or to maintain uncertainty appraised as opportunity.

When uncertainty appraised as danger cannot be reduced effectively, coping strategies can be employed to manage the emotional response.

When uncertainty appraised as danger cannot be reduced effectively, coping strategies can be employed to manage the emotional response.

The longer uncertainty continues in the illness context, the more unstable the individual’s previously accepted mode of functioning becomes.

The longer uncertainty continues in the illness context, the more unstable the individual’s previously accepted mode of functioning becomes.

Under conditions of enduring uncertainty, individuals may develop a new, probabilistic perspective on life, which accepts uncertainty as a natural part of life.

Under conditions of enduring uncertainty, individuals may develop a new, probabilistic perspective on life, which accepts uncertainty as a natural part of life.

The process of integrating continual uncertainty into a new view of life can be blocked or prolonged by structure providers who do not support probabilistic thinking.

The process of integrating continual uncertainty into a new view of life can be blocked or prolonged by structure providers who do not support probabilistic thinking.

Prolonged exposure to uncertainty appraised as danger can lead to intrusive thoughts, avoidance, and severe emotional distress.

Prolonged exposure to uncertainty appraised as danger can lead to intrusive thoughts, avoidance, and severe emotional distress.

ACCEPTANCE BY THE NURSING COMMUNITY

Practice

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access