Use of NIC in practice, education, and research

In his book, The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood, James Gleick23 asserts that information is the fuel and vital principle that our world runs on. Gleick describes in-depth how information pervades all the sciences and transforms every branch of knowledge. Similarly, the evolutionary theorist, Richard Dawkins18 asserted “what lies at the heart of every living thing is not a fire, not warm breath, not a spark of life … rather if you want to understand life, you need to think in terms of information, words, instructions, and information technology.” (p. 112) Gleick’s and Dawkins’ notions of the centrality of information apply to all fields of science, including nursing. Information lies at the heart of nursing.

Information is knowledge. Nursing is a scientific discipline, and like all disciplines, nursing has a unique body of knowledge. According to Nursing’s Social Policy Statement: The Essence of the Profession,3 nursing’s purpose includes the application of scientific knowledge to the processes of diagnosis and treatment through the use of judgment and critical thinking within the context of a caring relationship that facilitates health and healing. As a branch of knowledge, nursing is comprised of information about the nature of health and illness, as well as the strategies and treatments to promote health and well-being.

Central to any scientific system of knowledge is having a means to classify and structure categories of information.11,23,35 NIC identifies the treatments nurses perform, organizes this information into a coherent structure, and provides the language to communicate with individuals, families, communities, members of other disciplines, and the general public. When NIC is used to document the work of nurses in practice, then we have the beginning of a mechanism to determine the impact of nursing care on patient outcomes. Clark and Lang16 reminded us of the importance of nursing languages and classifications when asserting, “If we cannot name it, we cannot control it, finance it, teach it, or put it into public policy.” (p. 27)

This chapter has three major sections. The first section addresses the use of NIC in practice, including how to select an intervention for a particular patient, implementation of NIC in a clinical practice agency, and the implementation and uses of NIC in computerized database information systems. The second section addresses use in education, including integrating NIC into nursing education curricula and how NIC is used for clinical decision-making in the Outcome-Present State-Test (OPT) model of reflective clinical reasoning. The third section focuses on the use of NIC in research with an emphasis on how NIC can be used in efficacy and effectiveness research.

Use of NIC in practice

Selecting an intervention

Nurses use clinical judgment with individuals, families, and communities to improve their health, to enhance their ability to cope with health problems, and to promote their quality of life. The selection of a nursing intervention for a particular patient is part of the clinical judgment of the nurse. Six factors should be considered when choosing an intervention: (1) desired patient outcomes, (2) characteristics of the nursing diagnosis, (3) research base for the intervention, (4) feasibility for doing the intervention, (5) acceptability to the patient, and (6) capability of the nurse.

Desired patient outcomes

Patient outcomes should be specified before an intervention is chosen. They serve as the criteria against which to judge the success of a nursing intervention. Outcomes describe behaviors, responses, and feelings of the patient in response to the care provided. Many variables influence outcomes, including the clinical problem; interventions prescribed by the health care providers; the health care providers themselves; the environment in which care is received; the patient’s own motivation, genetic structure, and pathophysiology; and the patient’s significant others. There are many intervening or mediating variables in each situation, making it difficult to establish a causal relationship between nursing interventions and patient outcomes in some instances. The nurse must identify for each patient the outcomes that can be reasonably expected and can be attained as the result of nursing care.

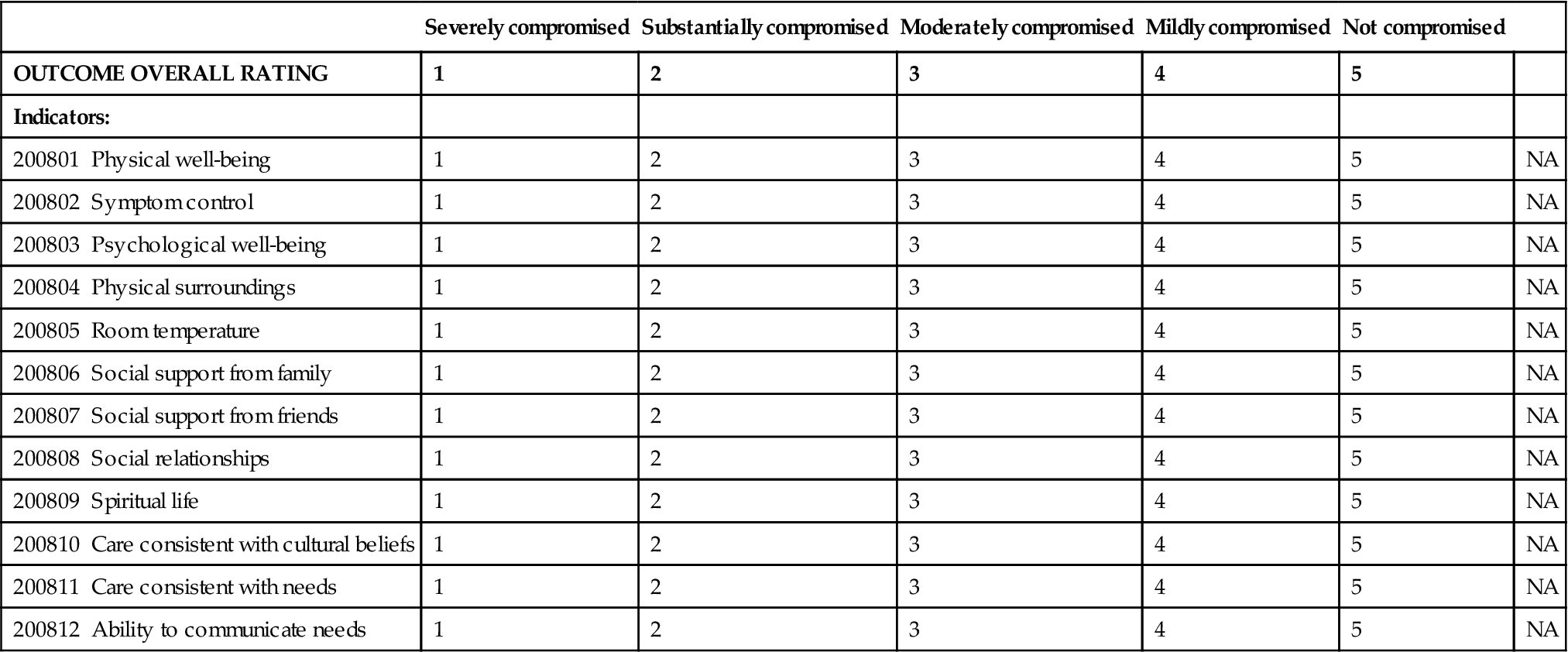

The most effective way to specify outcomes is by use of the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC).40 NOC contains 490 outcomes for individuals, families, and communities that are representative for all settings and clinical specialties. Each NOC outcome describes patient states at a conceptual level with indicators expected to be responsive to nursing intervention. The indicators for each outcome allow measurement of the outcomes at any point on a 5-point Likert scale from most negative to most positive. Repeated ratings over time provide identification of changes in the patient’s condition. Thus, NOC outcomes are used to monitor the extent of progress, or lack of progress, throughout an episode of care. NOC outcomes have been developed to be used in all settings, all specialties, and across the continuum of care. The NOC outcome of Comfort Status is displayed in Box 2-1 to show the label, definition, indicators, and measurement scale. NOC outcomes have been linked to NANDA International (NANDA-I) diagnoses, and these linkages appear in the back of the NOC book. NIC interventions have also been linked to NOC outcomes, and to NANDA-I diagnoses and those linkages are available in a book titled NOC and NIC Linkages to NANDA-I and Clinical Conditions: Supporting Critical Reasoning and Quality of Care.32

Characteristics of the nursing diagnosis

Outcomes and interventions are selected in relationship to particular nursing diagnoses. The use of standardized nursing language began in the early 1970s with the development of the NANDA nursing diagnosis classification. A nursing diagnosis according to NANDA-I is “a clinical judgment about individual, family, or community experiences/responses to actual or potential health problems/life processes” and “provides the basis for selection of nursing interventions to achieve outcomes for which the nurse has accountability.”41 (p. 515) The elements of an actual NANDA-I diagnosis statement are the label, the related factors (causes or associated factors), and the defining characteristics (signs and symptoms). Interventions are directed toward altering the etiological factors (related factors) or causes of the diagnosis. If the intervention is successful in altering the etiology, the patient’s status can be expected to improve. It may not always be possible to change the etiological factors and when this is the case, it is necessary to treat the defining characteristics (signs and symptoms).

To assist in selecting appropriate nursing interventions, Part Six in this book lists major and suggested interventions to treat NANDA-I nursing diagnoses. In addition, the recently published NOC and NIC Linkages to NANDA-I and Clinical Conditions: Supporting Clinical Reasoning and Quality Care32 text is an invaluable resource for identifying outcomes and interventions for all NANDA-I nursing diagnoses as well as for 10 common clinical conditions of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, colon and rectal cancer, depression, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, hypertension, pneumonia, stroke, and total joint replacement: hip/knee.

Research base for the intervention

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the report Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality25 outlined changes in the education of all health care professions that included employing evidence-based practice. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the IOM, and other government agencies that are clearinghouses for clinical guidelines have sanctioned the use of evidence-based practice as the basis for all health care delivery.24 These agencies have emphasized that interventions supported by research evidence improve patient outcomes and clinical practice. It is essential now that nurses develop clinical inquiry skills, which requires nurses to continually question if the care being given is the best possible practice. To determine the best practice, evidence based on research needs to be known and used in choosing interventions. Thus, the nurse who uses an intervention needs to be familiar with its research base. The research will indicate the effectiveness of using the intervention with certain types of patients. Some interventions and their corresponding nursing activities have been widely tested for specific populations, whereas others need to be tested and are based on expert clinical knowledge. Nursing diagnosis handbooks such as Ackley and Ladwig1 provide research references from case studies on a single client to systematic reviews that provide additional research evidence related to NIC interventions. Nurses learn about the research related to particular interventions through their education programs and also how to keep their knowledge current by finding and evaluating research studies. If there is no research base for an intervention to assist a nurse in the choosing of an intervention, then the nurse would use scientific principles (e.g., infection transmission) or would consult an expert about the specific populations for which the intervention might work.49 In addition, agencies use models such as the Iowa Model for Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality of Care to guide work on assembling evidence for treating a particular clinical problem and deciding on a practice protocol.50

Feasibility for performing the intervention

Feasibility concerns include the ways in which the particular intervention interacts with other interventions, both those of the nurse and those of other health care providers. It is important that the nurse is involved in the total plan of care for the patient. Other feasibility concerns, critical in today’s health care environment, are the cost of the intervention and the amount of time required for implementation. The nurse needs to consider the interventions of other providers, the cost of the intervention, and the time needed to adequately implement an intervention when choosing a course of action.

Acceptability to the patient

An intervention must be acceptable to the patient and family. The nurse is frequently able to recommend a choice of interventions to assist in reaching a particular outcome. To facilitate an informed choice, the patient should be given information about each intervention and how he or she is expected to participate. Most importantly, the patient’s values, beliefs, and culture must all be considered when choosing an intervention.

Capability of the nurse

The nurse must be able to carry out the particular intervention. In order for the nurse to be competent to implement the intervention, the nurse must: (1) have knowledge of the scientific rationale for the intervention; (2) possess the necessary psychomotor and interpersonal skills; and (3) be able to function within the particular setting to effectively use health care resources.9 It is clear from just glancing at the total list of 554 interventions that no one nurse has the capability of doing all of the interventions. Nursing, like other health disciplines, is specialized, and individual nurses perform within their specialty and refer or collaborate when other skills are needed.

After considering each of the above factors for a particular patient, the nurse would select the intervention(s). This is not as time consuming as it sounds when elaborated in writing. As Benner7 has demonstrated, the student and beginning nurse should examine these things systematically, but with experience, the nurse synthesizes this information and is able to recognize patterns rapidly. One advantage of the classification is that it facilitates the teaching and learning of decision-making for the novice nurse. Using standardized language to communicate the nature of our interventions does not mean that we stop delivering individualized care. Interventions are tailored to individuals by selective choice of the activities and by modification of the activities as appropriate for the patient’s age and the patient’s and family’s physical, social, emotional, and spiritual status. These modifications are made by the nurse, using sound clinical judgment.

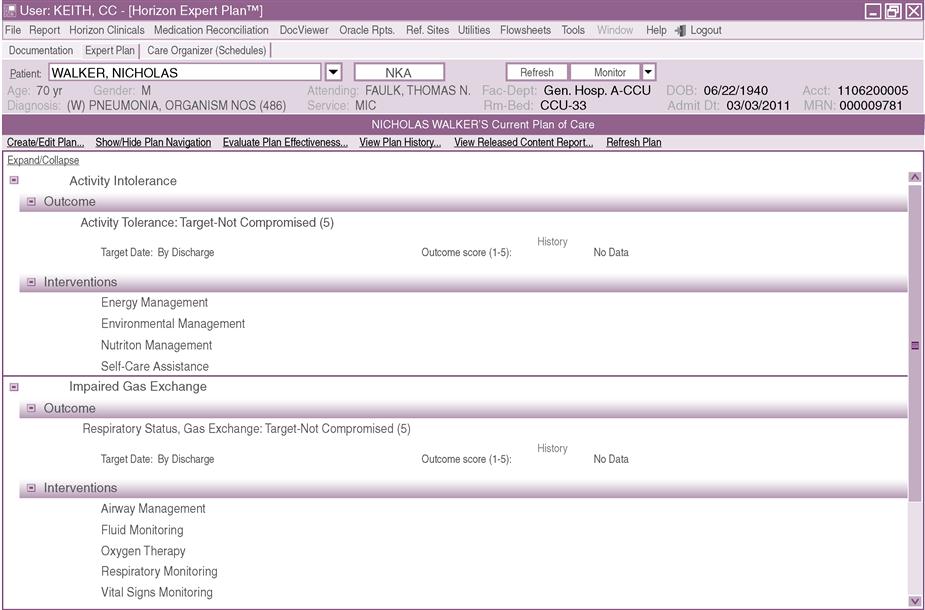

Implementing NIC in a clinical practice agency

Increasingly, a number of vendors who develop computerized clinical information systems (CIS) are including standardized nursing terminologies in hospital and health care settings. Anderson, Keenan, and Jones5 compared five nursing terminologies that included nursing diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes. There were 879 publications on the NANDA, NIC, and NOC (NNN) terminologies, more than the total publications for the four other terminologies combined. NNN literature was found in 21 countries and in 28 states in the United States. Thus, it is not surprising that NIC is being implemented into a wide range of computer information systems in the United States as well as countries around the world including Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Iceland, Japan, Spain, Switzerland, and The Netherlands. Box 2-2 lists some of the health care system computer vendors who have licensed NIC for incorporation into their software products. Computer documentation systems including NIC are currently being used in a large number of diverse health care settings. Including NIC along with other standardized nursing terminologies such as NANDA-I and NOC in computerized clinical information systems can be used not only to plan and document nursing care, but also provides a way to enhance clinical decision-making, share information, and track the achievement of patient outcomes.15, 34, 37, 38 Figure 2-1 is one example of how NIC appears in an electronic information system.

According to the Institute of Medicine report The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health,30 “there is no greater opportunity to transform practice than through technology.” (p. 136). As Gleick23 points out, the rise of placing information in mathematical and electronic form allows computers to rapidly process, store, and retrieve information. The IOM report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century28 cited numerous examples of how automated clinical information systems contribute to reduced errors, increased access to diagnostic tests and treatment results, and improved communication and coordination of care. Information systems also serve as an aid to clinical decision-making, documentation of care, and determination of the cost of care. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) (Public Law 111-5) in 2009 included provisions to create incentives for the adoption and meaningful use of health information technology. In order for nursing to be included in this initiative, it is essential that “nursing elements” be included in all electronic health records. Nursing elements of electronic records refer to any information related to the nursing diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes relevant to nursing. Casey14 points out that electronic health records will not benefit nursing until nurses are better able to describe their work, which will guide the design of information systems. Furthermore, nursing content in the electronic health record must be standardized and based on evidence-based practice. NIC is standardized and available in electronic form and ready to be integrated into health information systems. The use of NIC provides terms for clinical decision-making support, and enables the documentation, storage, and retrieval of clinical information about nursing treatments. Electronic implementation of standardized nursing languages facilitates the communication of nursing care provided to other nurses and health care providers; makes feasible a means for billing and the reimbursement for the provision of nursing care; and allows for the evaluation of the achievement of nursing outcomes and quality of nursing care. When electronic health record data, including NIC interventions, are stored in and retrievable from large data warehouses, nurses will be able to conduct large scale nursing effectiveness and cost effectiveness studies with comparisons among many different health care settings.37, 48

The time and cost for implementation of NIC into a nursing information system in a clinical practice agency depends on the agency’s selection and use of a nursing information system, the computer competency of nurses, and the nurses’ previous use and understanding of standardized nursing language. The change to use of nursing standardized language using a computer represents, for many, a major change in the way in which nurses have traditionally documented care, and effective change strategies need to be used. Complete implementation of NIC throughout an agency may take months to several years; the agency should devote resources for computer programming, education, and training. As major vendors design and update clinical nursing information systems that include NIC, implementation will be easier.

In this section we include tools for implementation. Box 2-3 provides steps for implementation of NIC in a clinical practice agency. Although not all of the steps must be done in every institution, the list is helpful in planning for implementation. We have found that successful implementation of the steps requires knowledge about change and nursing information systems. In addition, it is a good idea to have an evaluation process established. There are numerous publications that describe the processes of implementing NIC into a wide variety of practice settings, which can be located by a computer search of nursing literature. Those leaders who are directing the implementation effort as well as administrators, computer information system designers, and practicing nurses will benefit from reading the literature describing the implementation process. Box 2-4 includes “rules of thumb” for using NIC in an information system. Following these will help ensure that data are captured in a consistent manner. In some computer systems, due to space restrictions, there is a need to shorten some of the NIC activities. Although this is becoming less of a necessity as computer space for nursing expands, Box 2-5 provides guidelines for shortening NIC activities to fit in a computer system.

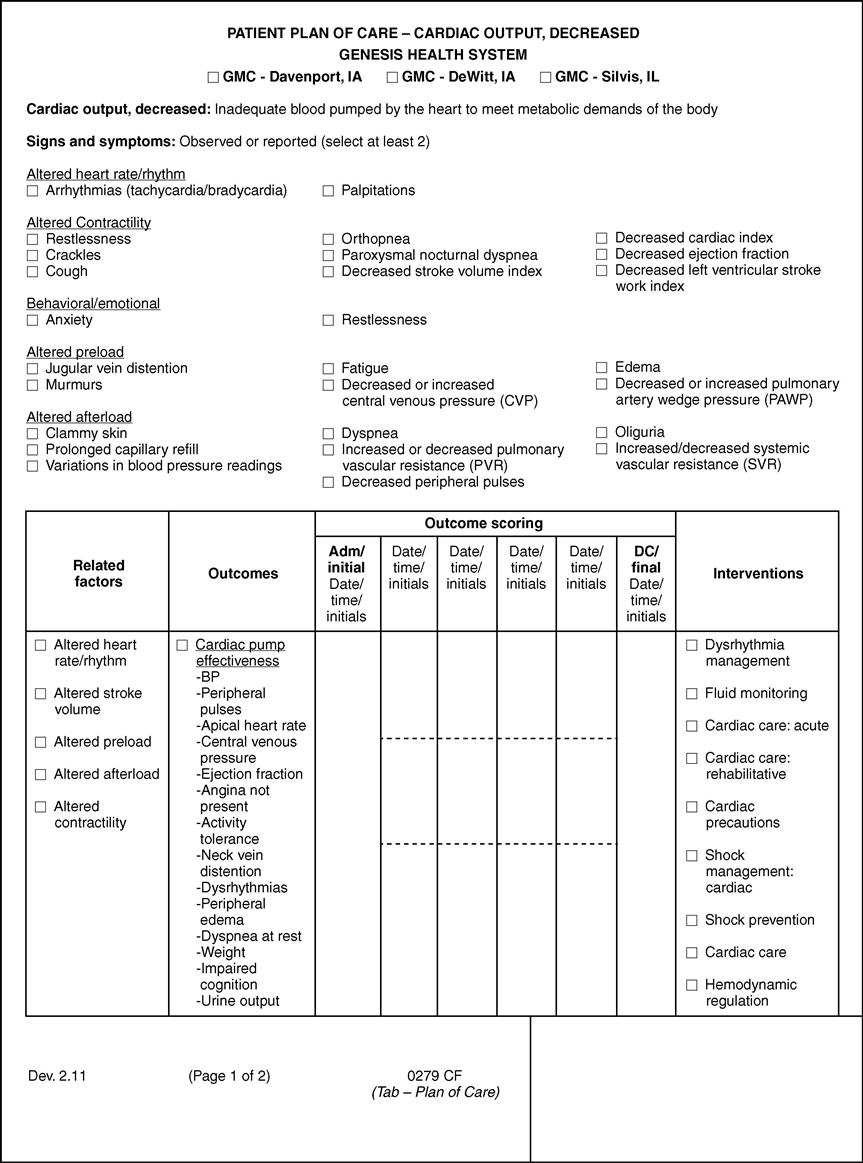

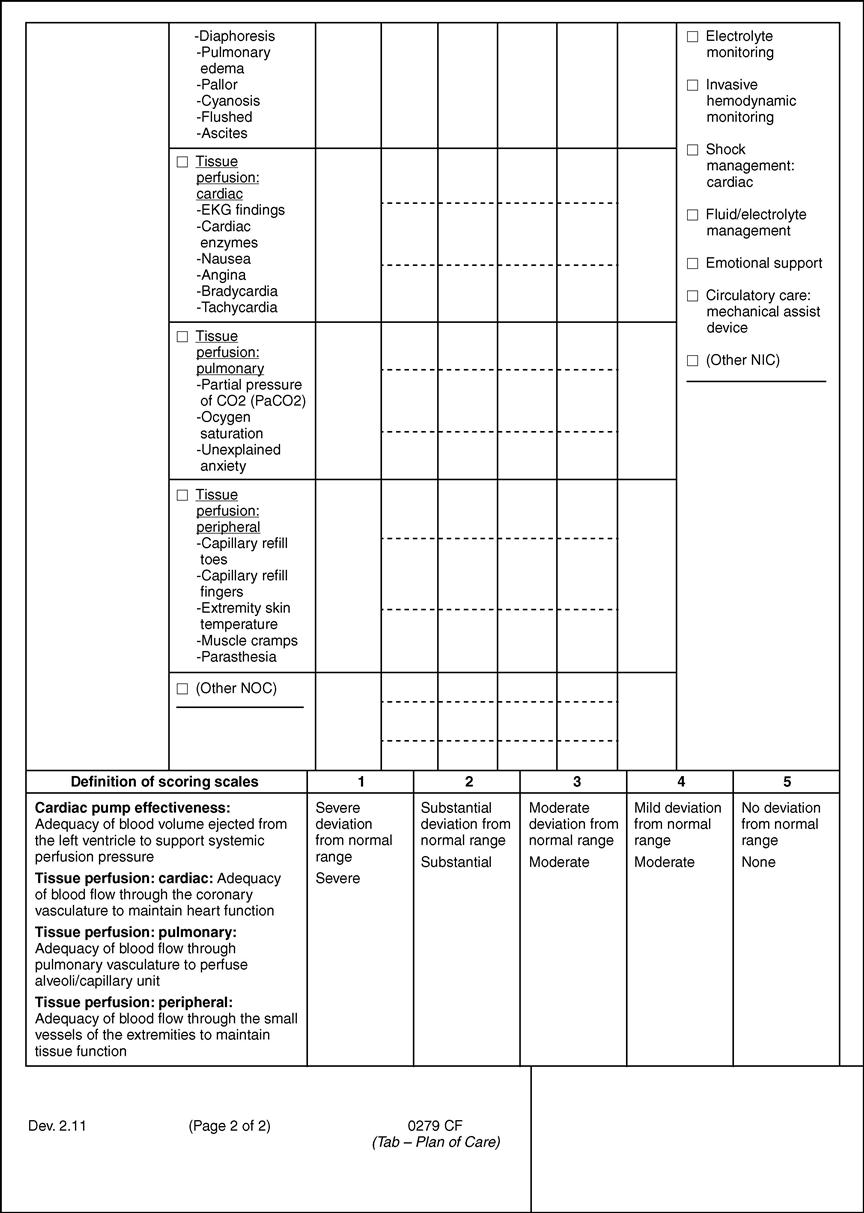

There is a national agenda to move to electronic health records; however, there are many settings in which manual nursing care plans are still used. It is very feasible to use standardized language in a manual/paper or non-computer system. In fact, implementation is easier if the nursing staff can learn to use standardized language before introduction of an electronic system. Figure 2-2 illustrates a manual nursing care plan that incorporates NANDA-I, NOC, and NIC. This is one of 68 care plans developed and used at Genesis Health Care System in Davenport, Iowa. This agency has been a field testing site for NIC for many years. At one point, they were entirely computerized but due to hospital mergers and a change in computer vendors the nursing care plans are currently manual.

Use of a standardized language model

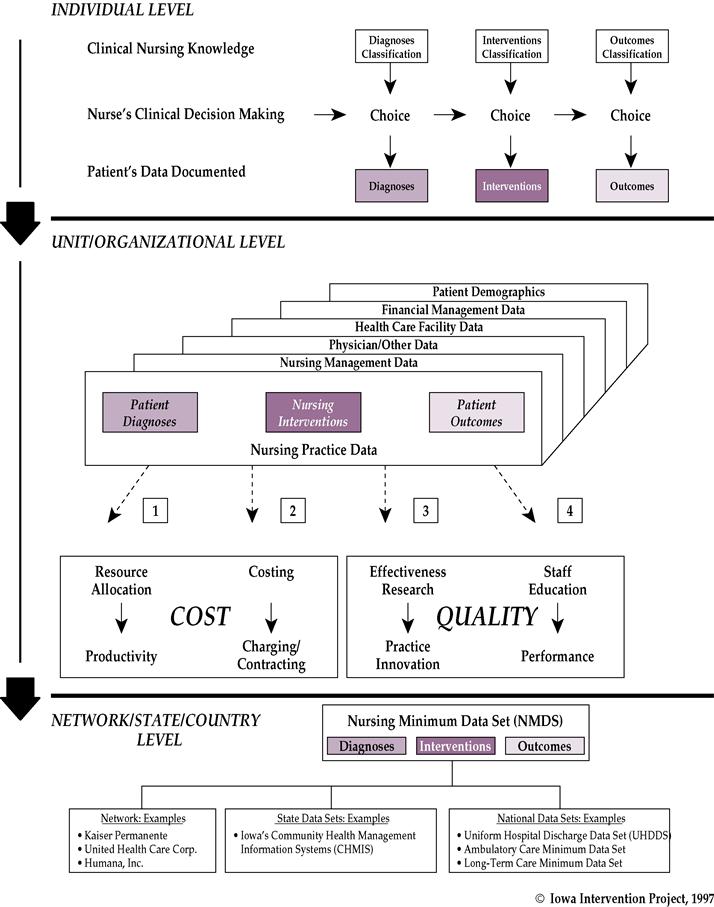

The model depicted in Figure 2-3 illustrates the use of standardized language for documentation of actual care delivered by the nurse at the bedside that generates data for decision-making about cost and quality issues in the health care agency. The data is also useful for making health policy decisions. The three-level model indicates that use of standardized language for documentation of patient care not only assists the practicing nurse to communicate to others but also leads to several other important uses.

At the individual level, each nurse uses standardized language in the areas of diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes to communicate patient care plans and to document care delivered. We recommend the use of NANDA-I, NIC, and NOC as the classifications in the areas of diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes. Each of these classifications is comprehensive across specialty and practice setting, and each has ongoing research efforts to maintain the currency of the classifications. An individual nurse working with a patient or group of patients/clients asks herself several questions according to the steps of the nursing process. What are the patient’s nursing diagnoses? What are the patient outcomes that I am trying to achieve? What interventions do I use to obtain these outcomes? The identified diagnoses, outcomes, and interventions are then documented using the standardized language in these areas. A nurse working with an information system that contains the classification will document care provided by choosing the concept label for the intervention. Not all of the activities will be done for every patient. To indicate which activities were done, the nurse could either highlight those done or simply document the exceptions, depending on the existing documentation system. A nurse working with a manual information system will write in the chosen NIC intervention labels as care planning and documentation are done. The activities can also be specified depending on the agency’s documentation system. Although the activities may be important in communicating the care of an individual patient, the intervention label is the place to begin when planning care.

This part of the model can be thought of as documentation of the key decision points of the nursing process using standardized language. It makes apparent the importance of nurses’ skills in clinical decision-making. We have found that, even though NIC requires nurses to learn a new language and a different way to conceptualize what they do (naming the intervention concept rather than listing a series of discrete behaviors), they quickly adapt and in fact become the driving force to implement the language. With or without computerization, the adoption of NIC makes it easier for nurses to communicate what they do, with each other and with other providers. Care plans are much shorter, and interventions can be linked to diagnoses and outcomes. Because an individual nurse’s decisions about diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes are collected in a uniform way, the information can be aggregated to the level of the unit or organization.

At the unit/organizational level, the information about individual patients is aggregated for all the patients in the unit (or other group) and, in turn, in the entire facility. This aggregated nursing practice data can then be linked to information contained in the nursing management database. The management database includes data about the nurses and others who provide care and the means of care delivery. In turn, the nursing practice and management data can be linked with data about the treatments made by physicians and other providers, facility information, patient information, and financial data. Most of these data, with the exception of data about treatments of providers other than physicians, are already collected in a uniform way and are available for use.

The model illustrates how the clinical practice data linked with other data in the agency’s information system can be used to determine both cost and quality of nursing care. The cost side of the model addresses resource allocation and costing out of nursing services; the quality side of the model addresses effectiveness research and staff education. The use of standardized language to plan and document care does not automatically result in knowledge about cost and quality but provides the potential for data for decision-making in these areas. The steps to accomplish resource allocation, costing out of nursing service, effectiveness research, and staff education are briefly outlined below. Explanation of some managerial and financial terms is provided in parentheses for those not familiar with these areas.

Cost

Resource allocation—distributing staff and supplies

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree