CHAPTER 10 Twenty-first Century Health Challenges

BACKPACK COMPLICATIONS

IV. Health Concerns/Emergencies

Table 10-1 Backpack Weight Limits

| Student’s Weight (lb.) | Backpack Maximum Weight (lb.) |

|---|---|

| 60 | 5 |

| 70 | 10 |

| 100 | 15 |

| 125 | 18 |

| 150 | 20 |

| 200 or more | 25* |

* 25 pounds is the maximum suggested safe limit.

Adapted from American Chiropractic Association (ACA) and American Physical Therapy Association (APTA).

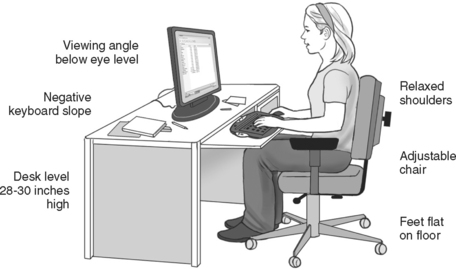

FIGURE 10-1 Appropriate and inappropriate backpack positioning.

A, Incorrect. Wearing the backpack over one shoulder tends to make one side of the body bear all the weight. This can cause an asymmetry of the spine and potential back pain, shoulder and/or neck strain, and loss of balance. B, Appropriate. Both shoulders bear the weight of the backpack load. Reduces symptoms of a heavy, unbalanced pack. C, Incorrect. Leaning forward with shoulders bending inward is observed when the pack is too low on the back and the load is not distributed evenly, producing bad posture, improper spine alignment, causing fatigue and/or back and neck strain. D, Appropriate. The backpack should rest evenly in the middle of the curve of the back. Wear chest straps and waist belt for appropriate weight distribution, stabilization, and reduction of potential pain or injury. See Box 10-1 for further information on backpack safety.

Box 10-1 EUPAC: Encourage Use of Proper Packing and Caution

1. Encourage weighing the pack and contents, limiting weight to no more than 15% of body weight to prevent neck and back strain.

2. Use wide and padded shoulder straps to avoid shoulder pressure and possible nerve damage.

3. Avoid slinging pack over one shoulder, which can cause loss of balance, muscle spasms, and low back pain.

4. A waist belt and chest straps provide good support and help with weight distribution and stabilization: fasten them. Adjust straps to allow arms to move freely.

5. Pack should not be longer than the distance between the shoulders and hips and not wider than the rib cage. It should rest in the curvature of the back.

6. Proper packing puts heaviest items close to the body and lighter items farther away or in small sections to distribute weight evenly, ease carrying, and prevent injury and strain.

7. Keep pack high up on the back. Do not wear low near the hips, because this shifts posture forward, producing back and neck strain.

8. Use caution when lifting a backpack. If the pack is very heavy, it should be placed on a desk or table before pulling it onto the back. Only pack what is needed for the day.

COMPUTER ERGONOMICS

IV. Health Concerns/Emergencies

Box 10-2 Tips to Avoid Eyestrain and Body Fatigue

1. Blink frequently to moisten eyes.

2. Wear computer glasses, as needed.

3. Focus on distant objects periodically.

4. Use relaxation and stretching exercises.

5. Move away from the computer occasionally.

6. Follow 20/20/20 rule: Every 20 minutes, take 20 seconds and look 20 feet.

20/20/20/ Rule and BBB Rule: From Dr. Jeff Anshel, personal conversation, Jan 25, 2007.

WEB SITES

Computer Ergonomics for Elementary School http://www.orosha.org/cergos/index.html

Cornell University Ergonomics Web http://ergo.human.cornell.edu

Corporate Vision Consulting http://www.cvconsulting.com

Stretch Break for Kids (Computer Ergonomics Exercises) http://www.paratec.com/sbform/kidsform.htm

SCHOOL TRENDS AND PHENOMENA

SCHOOL START TIME AND ADOLESCENTS

Adolescents experience a shift in circadian rhythms, the natural cycle of sleep–wake patterns, which causes a change in the secretion of the hormone melatonin. This change causes the adolescent to stay awake later at night and sleep later in the morning (National Sleep Foundation, 2006). Early school start times reduce the amount of sleep for most adolescents, and this lack of sleep impairs their cognitive and motor functioning, eye–hand coordination, accuracy, concentration, and short-term memory; it also shortens attention span and lengthens reaction time. Sleep deprivation affects specific areas of the brain and impacts how people learn. The brain needs more sleep than any other part of the body; during sleep, information received during the day is sorted out and consolidated (Peigneux et al, 2004; Spencer, Sunm, and Ivry, 2006). Lessons taught and learned at school—that is, new neuronal connections—are strengthened during sleep.

An adolescent requires 8.5 to 9.25 hours of sleep each night to function adequately (National Sleep Foundation, 2006). The most recent National Sleep Foundation Study reports that only 20% of adolescents get 9 hours of sleep, and almost 50% state that they get less than 8 hours, making them sleep deprived. Twelfth graders report that they get only 6.9 hours of sleep a night, making the senior year a particularly difficult time for adequate rest and sleep. Students find various coping mechanisms for sleep deprivation: 38% of high school students report taking at least two naps per week, they sleep later on weekends, and they frequently consume caffeine to stay awake—31% drank two or more caffeine drinks per day. Another sad consequence is that many give up exercising; they report being too sleepy or tired to do it. More than half (51%) of students who drive have driven while drowsy (National Sleep Foundation Study, 2006).

Sleep deprivation causes a negative mood: behavior and attitude of students lacking sleep show signs of anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and acting-out behaviors. They also have decreased focus, attention, and concentration in the classroom; 28% of students fall asleep during class at least once a week; 14% arrive late for morning class, skip that class, or miss school altogether. Most schools start between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m., so the average adolescent’s day starts between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m. (National Sleep Foundation Study, 2006). More than half of all high school students (55%) go to bed after 11 p.m. on school nights, robbing them of many needed hours of sleep. Those with optimal sleep (20%) receive more A and B grades (34%), and those with less sleep generally achieve lower grades (National Sleep Foundation Study, 2006).

Over 80 school districts throughout the United States (e.g., Minnesota, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Iowa) have a delayed start-time in high school. They found attendance improved, daytime alertness increased, and tardiness decreased. Students also reported less depression, fewer trips to the school nurse’s office, more frequent breakfasts, and the ability to complete more of their homework during school hours (Wahlstrom, 2002). Sleep is one factor among many that affects learning.

If advocating for later school start times, it is imperative that the school nurse:

1. Be aware of the research and current data in support of a later-start school day.

2. Gather data regarding school start times, sports, extracurricular activities, and transportation schedules.

3. Look at attendance rates, tardiness, and rates of skipping first classes as a rationale for change.

4. Recognize sleep-deprived adolescents and know symptoms exhibited (e.g., depression, mood changes, anxiety, frequent visits to nurse’s office). If sleep deprivation is suspected, take a sleep history, or ask the student to record sleep history in a log.

5. Educate parents and adolescents on changing sleep patterns related to learning.

6. Educate teachers and staff regarding sleep deprivation in adolescents.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree