CHAPTER 23

Trauma in Pregnancy

1 State the normal physiologic changes that potentially affect the evaluation of a pregnant trauma patient.

2 Identify the major mechanisms of injury that affect the pregnant trauma patient.

3 Describe the components of the primary and secondary survey for a pregnant trauma patient.

4 List interventions to prevent maternal and fetal mortality resulting from trauma.

5 Develop a plan of care for a pregnant patient experiencing blunt or penetrating trauma.

6 Demonstrate knowledge of the physiologic changes of pregnancy and the specific mechanisms of injury in the assessment, diagnosis, planning, intervention, and evaluation of a pregnant trauma patient and her fetus.

7 Interpret physiologic assessment and diagnostic findings to establish priorities for the care of the pregnant trauma patient and her fetus.

8 Identify health promotion needs, and promote behavioral changes that produce healthy outcomes of pregnancy.

INTRODUCTION

1. Trauma is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide and the leading cause of maternal death during pregnancy.

a. In the United States, 6% to 7% of all pregnant women experience some sort of trauma, with the greatest frequency in the last trimester (Tweddale, 2006).

b. Trauma is more likely to cause maternal death than any other medical complication of pregnancy (Mattox & Goetzl, 2005).

c. The most common cause of maternal death by trauma is serious abdominal injury leading to hemorrhagic shock and head injury (Ikossi, Lazar, Morabito, Fildes, & Knudson, 2005).

d. The most common cause of fetal death is maternal death and maternal shock; fetal demise results 80% of the time when the mother experiences hemorrhagic shock (McGowan Repasky, 2007).

2. Injury to the pregnant patient can result from forces causing blunt or penetrating trauma.

a. Blunt trauma is the most frequent cause of maternal and fetal injury (McGowan Repasky, 2007).

b. The most common causes of blunt trauma are motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), falls, and assaults.

(1) Blunt trauma might result from force applied to the abdomen from direct impact or as a result of secondary injury from abdominal organ displacement and hemorrhage from coup-contrecoup event (Tweddale, 2006).

(2) Rapid compression, deceleration, or shearing forces can also result in abruptio placentae (McGowan Repasky, 2007).

(3) Blunt abdominal trauma can lead to retroperitoneal bleeding as well as pelvic fractures, abruption, rupture, or premature onset of labor (Muench & Canterino, 2007).

c. Penetrating trauma occurs most frequently from gunshot or stab wounds, with gunshot wounds being more common.

d. Fetal injury is more common during the third trimester when the head is relatively fixed in the pelvis and less amniotic fluid is present to buffer energy transfer (Tweddale, 2006).

e. The incidence of intentional injury from domestic violence rises during pregnancy (El Kady, Gilbert, Xing, & Smith, 2005).

B Important concepts for trauma in pregnancy

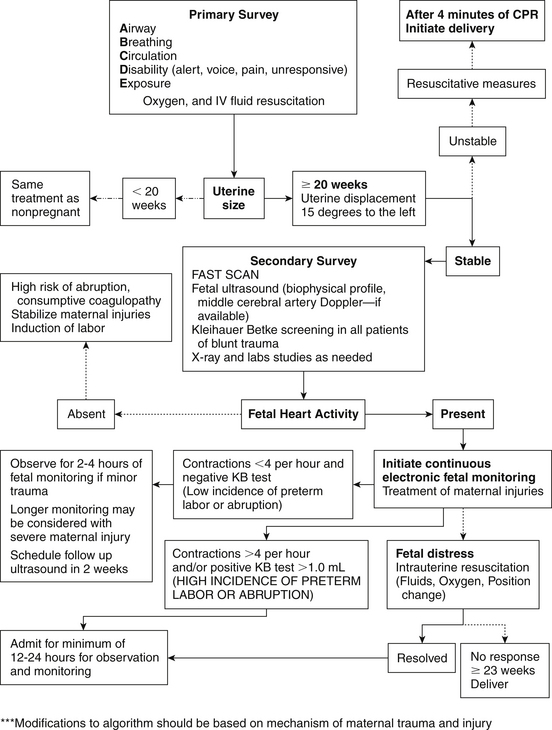

1. The initial goal in trauma evaluation is maternal stabilization.

a. Resuscitation during pregnancy proceeds as in any other trauma patient.

b. The primary assessment includes the ABCs: Airway, Breathing, Circulation, and cervical spinal precautions, as well any emergent interventions needed to support the ABCs.

c. The secondary assessment includes a full set of vital signs (including fetal heart rate [FHR]), brief overall examination (maternal and fetal), and important historical data; further injury-focused assessments are completed once all of the injuries are identified.

2. Trauma in pregnancy involves two patients: woman and fetus.

a. Minor injuries to the woman might cause significant or fatal injury to the fetus.

b. Maternal outcome in trauma corresponds to the injury, whereas fetal outcome depends on the injury and the maternal physiologic response.

c. Early recognition of pregnancy assists in identification of pregnancy-related changes that might alter assessment findings and mask signs of shock (Ikossi et al, 2005).

3. Proper seatbelt use prevents ejection during motor vehicle collisions; ejection from vehicles frequently results in head trauma with high maternal and fetal death rates.

4. Risk factors predictive of fetal death include young age, history of smoking or alcohol use, placental abruption, maternal ejection from MVA, maternal death, maternal hypotension, maternal hypoxia, younger gestational age, lack of restraints from MVA, and an injury severity score greater than 9 (Aboutanos et al, 2007; El Kady, 2007; Muench & Canterino, 2007).

5. Frequently, trauma cases involve litigation; accurate, well-documented records protect patients as well as the health care system.

C Important physiologic considerations for trauma in pregnancy (altered physiologic state of the pregnant patient alters the patient’s response to trauma) (Muench & Canterino, 2007).

a. Blood volume increases 50%, and of this, plasma volume increases 30% to 40% and red blood cell volume only increases 20% to 30%, leading to a physiologic anemia in pregnancy (Gordon, 2007; Tsuei, 2006).

(1) By the third trimester, maternal cardiac output peaks at 50% above nonpregnant values, which is indicated by an increase in baseline normal heart rates of 10 to 15 beats per minute (bpm).

(2) Blood pressure change also occurs with a 5 to 15 mm Hg drop in the systolic and diastolic readings (Muench & Canterino, 2007).

(3) The maturing fetus causes marked increases in uterine blood flow, which can comprise 20% of cardiac output at term (Tsuei, 2006); maternal perfusion pressure is needed to maintain uterine blood flow.

b. Pregnant women in shock might not have cool, clammy skin typical of shock because of normal maternal vasodilation in the first and second trimesters (Tweddale, 2006).

(1) The physiologic changes in pregnancy might delay the usual vital sign changes of hypovolemia; blood loss of up to 1500 mL can occur without a change in maternal vital signs.

(2) A 15% to 30% reduction of uterine blood flow can occur without change in maternal blood pressure; fetal compromise can occur before there are any changes in maternal vital signs.

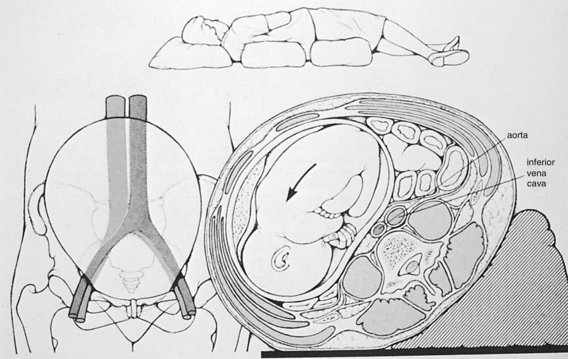

c. Compression of the inferior vena cava, from the fetus, when the mother is in a supine position (after 20 weeks’ gestation) can result in a systolic blood pressure drop of up to 30 mm Hg and a 28% cardiac output decrease (Tsuei, 2006); by displacing the uterus to the left when a supine position or spinal immobilization is required, the compression can be relieved (Figure 23-1).

d. Because the fetal heart rate is often the first vital sign to change, all pregnant trauma patients need continuous fetal heart rate monitoring.

2. Respiratory changes affect maternal and fetal outcome when trauma occurs.

a. Hormonal and mechanical (enlarging uterus) changes combine to produce hyperventilation (Ladewig, London, & Davidson, 2010).

(1) The elevation of the diaphragm by the gravid uterus results in a 20% decrease in functional residual capacity (FRC); increased maternal oxygen consumption, and diminished oxygen reserves occur, increasing susceptibility to hypoxia (Ramsay, 2006).

(2) Minute ventilation and tidal volume are increased 40% and respiratory rate will increase, leading to a predisposition for rapid hypoxemia with apnea (Torgersen & Curran, 2006).

b. PaO2 is normal or slightly increased, but the PaCO2 decreases to 27 to 32 mm Hg; a compensated respiratory alkalosis occurs with the pH remaining in the normal range due to increased excretion of bicarbonate by the kidneys (Yeomans & Gilstrap III, 2005).

(1) Anxiety and pain can cause respiratory rate increases that result in hypocapnia and can lead to faintness and perioral numbness.

(2) Capillary engorgement of the mucosa causes swelling of the respiratory tract, severely compromising the airway, making intubation more difficult (Muench & Canterino, 2007).

c. Maternal hypoxia (diminished oxygen reserve) affects fetal oxygenation; therefore, fetal heart rate changes might indicate maternal hypoxia; arterial blood gas measurement is the best indicator of maternal status (Witcher, 2006).

3. Gastrointestinal changes occur during pregnancy.

a. The small bowel is pushed up by the uterus, and the large bowel moves posteriorly; penetrating trauma might injure multiple loops of bowel (Cunningham et al, 2005).

(1) Diminished bowel sounds might be normal or indicate intraperitoneal injury (Smith, 2009).

(2) Chronic distention of the parietal peritoneum by the uterus reduces the symptoms of intraperitoneal bleeding, such as rigidity and guarding (Chames & Pearlman, 2008).

b. Progesterone causes smooth muscle relaxation, and lower esophageal sphincter tone is decreased (Tsuei, 2006), increasing the need for a nasal gastric tube in the trauma pregnant patient.

c. The enlarged uterus is vulnerable to injury but can protect the maternal abdominal organs (spleen, liver, kidneys, bowel).

4. The genitourinary system changes in pregnancy increase the risk of injury.

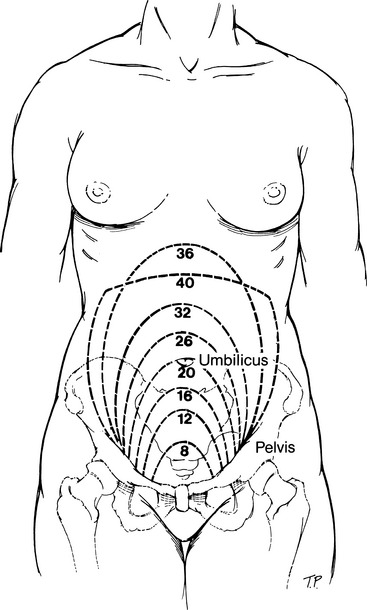

a. The bladder moves from the pelvic area to the abdominal area by 12 weeks’ gestation, increasing the risk of traumatic injury (Constanty & Cruz, 2006). Figure 23-2 shows uterine size and location, reflecting gestational age.

b. Renal blood flow increases in pregnancy, the serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen values are lower, and hydronephrosis is common due to the smooth muscle–relaxing properties of progesterone.

5. The hematologic changes that occur in pregnancy put the pregnant trauma patient at risk for disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

a. Platelet levels might be normal or slightly lower than normal.

b. Fibrinogen levels are doubled by the third trimester.

c. There is an increase in clotting factors VII, VIII, IX, and X that can result in hypercoagulopathy and increased thromboembolic risk (Constanty & Cruz, 2006).

6. The pelvis becomes more flexible during pregnancy, and a widening occurs.

E Cause or mechanism of injury

1. Motor vehicle accideats (MVAs)

a. MVCs account for most traumas and are the leading cause of more serious maternal injury (66% to 67%) (El Kady, 2007; Schiff & Holt, 2005).

b. Lack of seatbelt use contributes to increased morbidity and mortality (Sirin, Weiss, Sauber-Schatz, & Dunning, 2007) by increasing the number of patients who have been ejected from the vehicle as well as the number receiving blunt head and abdominal trauma.

c. Head and blunt abdominal injuries are the most common causes of maternal death.

d. Maternal death is the most common cause of fetal death.

e. MVAs are the most frequent cause of blunt injury, which can result in abruptio placentae, uterine rupture, and preterm labor.

f. Pelvic fracture occurs most often with an MVA and can cause massive bleeding as well as fetal skull fracture.

a. Falls are the second most common cause of blunt trauma in pregnancy (26%) (Schiff, 2008).

b. Head and spinal cord injuries, and fractures of the pelvis and lower extremities are common because a pregnant woman is likely to fall on her buttock or side (Schiff, 2008).

c. Observation for abruptio placentae is important.

d. Details of the fall, such as the height of the fall and landing surface material, can be important factors to consider when assessing for injuries.

a. Assaults are rapidly edging out falls as the second leading cause of injury to pregnant women, especially in urban areas; assaults cause blunt and penetrating injuries.

b. Assaults might cause death, direct maternal or fetal injury, preterm labor, and abruptio placentae.

c. Domestic violence affects up to 20% of women (American Academy of Pediatrics[AAP] and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2007); domestic violence is rarely an isolated event and often escalates in pregnancy (see Chapter 18 for a complete discussion of intimate partner violence in pregnancy); any nonvehicular trauma in pregnancy warrants domestic violence screening (El Kady et al, 2005).

d. Younger pregnant women (ages 15 to 24) are more likely to be hospitalized for assault than older pregnant women (El Kady et al, 2005).

a. The incidence of burns is low, but burns are detrimental to fetal survival (Tweddale, 2006).

(1) Burns are generally caused from flames or hot liquids.

(2) Fetal survival is influenced by gestational age and maternal survival, as well as the total body surface area (TBSA) burned.

b. Inhalation injuries and carbon monoxide intoxication should always be suspected in the burn victim.

(1) Carbon monoxide poisoning impairs the release of oxygen from the mother to the fetus and from the fetal hemoglobin to fetal tissue (Kennedy, McMurtry Baird, & Troiano, 2008).

(2) Concentration of carboxyhemoglobin is 10% to 15% higher in the fetus than in the mother, and the fetal half-life of carbon monoxide is twice as long as that of the maternal half-life (Kennedy et al, 2008).

(3) Automobile exhaust and faulty heating systems are also major causes of carbon monoxide poisoning (the leading cause of all poisoning deaths).

a. Gunshot wounds are the more common of the two and usually require surgical exploration and repair.

b. The uterine muscle absorbs energy from penetrating bullets, which decreases the velocity and lessens the likelihood of visceral injury (Tweddale, 2006).

c. Penetrating wounds to the uterus can cause significant injury to the fetus (70%), but they generally result in a good maternal outcome (Mattox & Goetzl, 2005).

d. With penetrating injury above the umbilicus after the second half of pregnancy, there is an increased likelihood of injury to the bowel.

CLINICAL PRACTICE

a. A brief history is obtained if possible, including chief complaint, mechanism of injury, previous assessment, and treatment.

[i] Position in vehicle (driver, passenger, front, rear)

[ii] Restraints used (shoulder harness, lap belt, three-point restraint, helmet)

[iii] Speed of all vehicles involved in collision

[iv] Point of impact: head on, rear, or side collision (T-bone) and amount of intrusion into the passenger compartment

2. Primary maternal assessment: rapid, brief assessment of the patient to identify any life-threatening problem requiring immediate intervention per Trauma Nursing Core Course guidelines (Emergency Nurses Association [2007]) (Figure 23-3)

(b) Stridor, noisy, or absent respirations

(c) Vomitus, teeth, blood, secretions, or debris in upper airway

(d) Substernal and intercostal retractions

(e) Decreased level of consciousness

(f) Soft tissue damage to the face and neck

(3) Interventions if airway obstruction

(a) Jaw-thrust maneuver to open airway

(b) Gentle oral suction to remove vomitus, blood, secretions, and so on

(c) Insertion of oral or nasal airway to maintain airway if needed

(4) Cervical spine precautions

(a) Apnea or agonal respirations less than 10 per minute

(b) Shallow, ineffective respirations

(c) Unequal or absent breath sounds

(d) Asymmetry of chest wall expansion, severe retractions

(e) Tracheal shift or distended neck veins

(f) Obvious chest wounds, such as an open pneumothorax; impaled object in chest; multiple rib fractures

(g) Decreased level of consciousness

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree