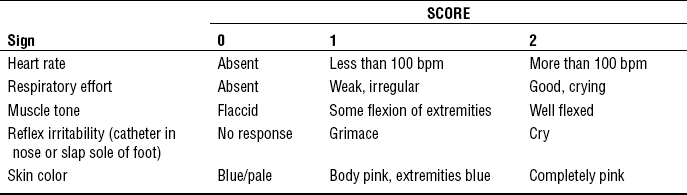

CHAPTER 16 1 Describe the cardiovascular, pulmonary, thermal, and gastrointestinal adaptation of the newborn. 2 Identify indications for instituting neonatal resuscitation. 3 Identify parameters used in the Apgar scoring of a newborn. 4 Describe the importance of maintaining a neutral thermal environment for the newborn, and discuss interventions to achieve a neutral thermal environment. 5 Identify normal physical characteristics of the newborn. 6 Interpret physical and neurologic findings for gestational age classification. 7 Define sensory capabilities of the newborn. 8 Define nutritional needs of the normal newborn, and assess readiness and ability of the newborn to feed orally. 9 Distinguish sleep and wake cycles of the newborn. 10 Devise a health education plan for a particular situation. Transition from fetus to neonate requires profound physiologic adaptation. Surprisingly, most neonates make this transition without difficulty (Pinheiro, 2009). Key elements in the birth transition are (1) shift from maternally dependent oxygenation to continuous respiration; (2) change from fetal circulation to mature circulation with increase in pulmonary blood flow and loss of left-to-right shunting; (3) commencement of independent glucose homeostasis; (4) independent thermoregulation; and (5) oral feedings (Engle & Boyle, 2005). Close observation of the infant’s adaptation to extrauterine life is imperative to identify problems in transition and initiate interventions. A Transition from fetus to neonate a. Mechanical stimuli: Compression of the fetal chest during vaginal delivery creates negative pressure by which air is drawn into the lung fields as the thorax recoils to its original size when the fetus exits the mother’s body. Air fills the alveoli by replacing the lung fluids that have been expelled by chest compression during the vaginal delivery. The remaining lung fluids are removed through reabsorption by the lymphatics. Infant crying creates intrathoracic positive pressure, keeping the alveoli open. b. Chemical stimuli: With cessation of placental blood flow, the neonate’s lungs must initiate and maintain gas exchange. The stress on the fetus during delivery leads to mild hypoxia, elevated carbon dioxide, and acidosis. Aortic and carotid bodies contain chemoreceptors that stimulate the medulla to trigger respiration. Surfactant, a phospholipid coating the alveolar epithelium, reduces the surface tension of the lung mucosa and allows exhalation without lung collapse. c. Thermal stimuli: Sudden chilling of the moist infant after delivery stimulates skin sensory receptors to transmit impulses to the respiratory center. d. Sensory stimuli: Normal handling after delivery (e.g., vigorous drying of the newborn) provides strong tactile stimulation to initiate breathing. 2. Cardiovascular adaptation: The neonate’s circulatory system undergoes several physiologic changes after birth. The termination of fetal circulation and the transition to newborn circulation involve the closure of the three fetal shunts—the ductus venosus, the foramen ovale, and the ductus arteriosus. a. The physiologic changes associated with lung inflation after delivery cause an increase of pressure in the left heart and increase systemic resistance. b. With neonatal respiration, oxygenated blood enters the pulmonary musculature. This dilates the pulmonary artery and decreases the pulmonary vascular resistance. c. The ductus arteriosus functionally closes by 10 to 15 hours in the full-term infant due to decreasing pressure in the pulmonary vasculature and the increased pressure in the aorta (Blackburn, 2006). This stops the flow of blood through the ductus arteriosus. d. Vascular dilation along with the equalization and eventual overriding left atrial pressure forces functional closure of the foramen ovale. The foramen ovale, which acts like a flap valve, closes within minutes after birth with the decreased pulmonary vascular resistance and increased left heart pressure due to termination of placental blood flow (Blackburn, 2006). a. Thermoregulation (a critical component in the physiologic adaptation to extrauterine life) is the means by which the neonate’s body temperature is maintained by balancing heat generation and heat loss in a changing environment. b. Normal temperature range: Preferred temperatures for term infants are between 36° (96.8° F) and 36.5° C (97.7 F) (axillary) for the first few hours of life. Newborns are at an increased risk of thermoregulatory problems for several reasons (Galligan, 2006; Hackman, 2001). (1) The ratio of large body surface to body mass (2) Higher metabolic rate with limited stores of metabolic substrates (3) Limited subcutaneous fat with poorly developed shivering response (1) Convection: Heat is lost to air or fluid around the infant that is cooler than infant’s temperature (e.g., air drafts on infant from open door in delivery room). (2) Radiation: Heat is lost to solid objects near infant that are cooler than infant’s temperature (e.g., windows to the outside not covered by draperies). (3) Conduction: Heat is lost to cold surfaces or to objects with which the infant has contact (e.g., x-ray plate or unheated mattress or scale). (4) Evaporation: Heat is lost when water evaporates from the infant’s skin surface or respiratory tract (e.g., infant not dried immediately after birth). d. Newborns attempt to regulate body temperature through flexed fetal positioning, which decreases body surface area; peripheral vasoconstriction; increased metabolic rate; and nonshivering heat production by brown fat metabolism (London, Wieland-Ladewig, Ball, & Bindler, 2007). e. Neutral thermal environment (NTE): An NTE is the temperature range in which normal body temperature can be maintained with minimal metabolic demands and oxygen consumption. (a) Incubator: usually single-walled plastic boxes that warm the infant by convection (b) Radiant warmers: an open bed with radiant heat panels placed above the infant; convective and evaporative heat losses are increased (c) Open crib: Once an infant’s temperature is normalized, infant is placed in an open crib with hats and blankets, providing thermal support. 4. Gastrointestinal transition: Feedings initiated as soon as possible after birth help maintain normal metabolism during the transition from fetal to extrauterine life (Heird, 2007). The goal of feeding is to provide adequate nutrition to meet the infant’s metabolic requirements and ensure growth. a. Infants born beyond 32 to 34 weeks’ gestation have adequate suck-and-swallow coordination for oral feedings unless neurologic damage has occurred or the infant is too ill to safely handle feedings. (1) Breastfeeding: See Chapter 14 for a complete discussion of breastfeeding. (a) The best source of nutrition in the first 6 months of life is human milk (Eiger, 2009); provides 20 kcal/ounce (30 mL). (b) Should begin as soon as possible after birth, usually within the first hour and continue for at least 12 months (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2005) (c) Unless medically contraindicated, alert, healthy infants should have their first feeding in the delivery room. Early breastfeeding in the delivery room has been shown to increase the percentage of mothers who continue breastfeeding at 2 and 4 months postpartum (Schanler, 2009). (d) Feed every 2 to 3 hours or when infant is awake, alert, and demonstrating behavioral feeding cues (rapid eye movements under the eyelids, sucking movements of the mouth and tongue, hand-to-mouth movements, body movements, small sounds) (Walker, 2007). Each session should last 10 to 15 minutes on each breast. Burp infant between and after each breast. (e) Do not supplement the breastfed infant with feedings of water, glucose water, or formula, which might actually discourage breastfeeding. [i] Lower incidence and/or severity of a many infectious diseases including diarrhea, respiratory tract infections, otitis media, bacteremia, bacterial meningitis, urinary tract infections, necrotizing enterocolitis (AAP, 2005; Schanler, 2009) [ii] Possible protective effect against sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), type 1 diabetes mellitus, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and asthma (AAP, 2005) [iii] Economic benefit for the family and society related to reduced health care costs and reduced employee absenteeism for care related to infant illness (Krebs & Primak, 2006) [iv] Psychological benefits related to enhanced infant and maternal bonding and attachment (a) Commercially prepared formulas are based on cow’s milk and have been modified to closely resemble human milk. Provides 20 kcal/ounce (30 mL). (b) The first feeding should be initiated in the nursery. Infant should be offered several sips of sterile water before formula to assess for aspiration. (c) Bottle-fed infants should be fed 15 to 30 mL of formula every 3 to 4 hours on first day of life increasing to 75 to 90 mL by day 4 or 5. (d) Always hold infant during feedings; this provides vital human contact. Bottle-propping can lead to aspiration and middle-ear infections. (e) Discard all unused formula left in bottle after feeding. [i] Ability to share feedings with partner, family, and friends [ii] Lack of physical problems (i.e., sore nipples, nipple confusion, etc.) (a) Pacifier use is recommended once breastfeeding is well established (approximately 1 month of age) (AAP, 2005). (b) Advantage: provides nonnutritive sucking and comfort for a crying infant and may increase arousability of infants during sleep reducing the risk of SIDS (Hunt & Hauck, 2007; Schwartz & Guthrie, 2008) (c) Disadvantages: source of bacteria if not cleaned properly, potential for compulsive use, may interfere with normal teeth positioning and eruption and cause alteration in bone growth (Schwartz & Guthrie, 2008) 1. Identify the infant at risk. a. Review maternal history and prenatal course. b. Assess fetal well-being during labor and delivery. (a) This scoring system, initially developed by Virginia Apgar in 1952, provides practitioners with a standardized approach for assessing the newborn infant immediately after birth to help identify those infants requiring resuscitation and predict survival in the neonatal period (Stoll, 2007). (b) Scoring is done at 1, 5, and sometimes 10 minutes of life; the newborn is given a score from 0 to 2 for each category, based on the elements described in Table 16-1. (2) Indications for postive pressure ventilation with a tightly fitted face mask using 100% supplemental oxygen (AHA & AAP, 2006) (3) Indications for chest compressions over the lower third of the sternum at a rate of 120/min (4) Indications for medication (a) HR <60 bpm after a minimum of 30 seconds of adequate ventilation and chest compressions. Administer epinephrine intravenously (IV) at a dose of 0.01 to 0.03 mg/kg. (5) Indications for endotrachael intubation 1. After stabilization, a thorough and systematic assessment of the newborn is necessary to identify the state of health of the neonate and detect congenital anomalies that might cause problems with extrauterine adaptation. Physical examination of the term infant should be performed with one or both parents in attendance. This fosters discussion with parents about expected physical and behavioral characteristics of their newborn. a. Weight: 2500 to 4000 g (5 pounds, 8 ounces to 8 pounds, 13 ounces) b. Length from head to heel: 48 to 53 cm (19 to 21 inches) c. Chest circumference: 30.5 to 33 cm (12 to 13 inches) a. Temperatures should stabilize between 36.4° and 37° C (97.5° and 98.6° F). b. Respiratory patterns are irregular, with respiratory rates between 30 to 60 inspirations per minute. c. Heart rates are regular, with rates between 110 and 160 bpm depending on the infant’s state. d. Blood pressure measurements are usually not assessed as part of the newborn examination. a. General survey: periods of alertness, symmetric features and movements, easily consolable b. Skin: smooth, pink to reddish with possible flaking in areas of major creasing. Vernix caseosa, a cheesy white substance, can be found on the entire body but is more intense between folds. Lanugo, a fine hair, might be seen, especially on the back. (a) Acrocyanosis: cyanosis of hands and feet (b) Cutis marmorata: transient mottling, especially when exposed to cool temperatures (c) Erythema toxicum: pink papular rash with vesicles on chest, abdomen, back, buttocks, and extermities (d) Capillary hemangioma: “stork bite” and “angel kiss” are flat, deep pink areas over eyelids, forehead, or nape of neck in infants with fair skin. (e) Mongolian spots: bluish black hyperpigmented areas usually located on the back and buttocks in infants with dark skin (1) Molding of the head might occur as the result of the delivery and usually resolves within a few weeks. Bruising is common. (a) Caput succedaneum: presents at birth with pitting edema of the scalp crossing suture lines as a result of accumulation of blood or serum above the periosteum (Fuloria & Kreiter, 2002). (b) Cephalhematoma: occurs several hours after birth from bleeding between the periosteum and skull, causing swelling that does not cross suture lines; might take several weeks to resolve (1) Eyelids are usually edematous immediately after birth. (2) Color of iris: slate gray, dark blue, or brown (3) Pupils reactive to light; red reflex present; focuses on objects and follows to midline (4) Mucoid discharge is normal with absence of tears. (1) Position: Top of pinna is horizontal to outer canthus of eye. (2) Pinna is flexible and well formed with cartilage present. (1) Intact palate with midline uvula (2) Normal frenulum of tongue and lip (3) Minimal or absent salivation (1) Full range of motion without torticollis (asymmetic shortening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle) (3) Intact clavicles with no tenderness, swelling, or crepitation

Transitional Care of the Newborn

INTRODUCTION

CLINICAL PRACTICE

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree