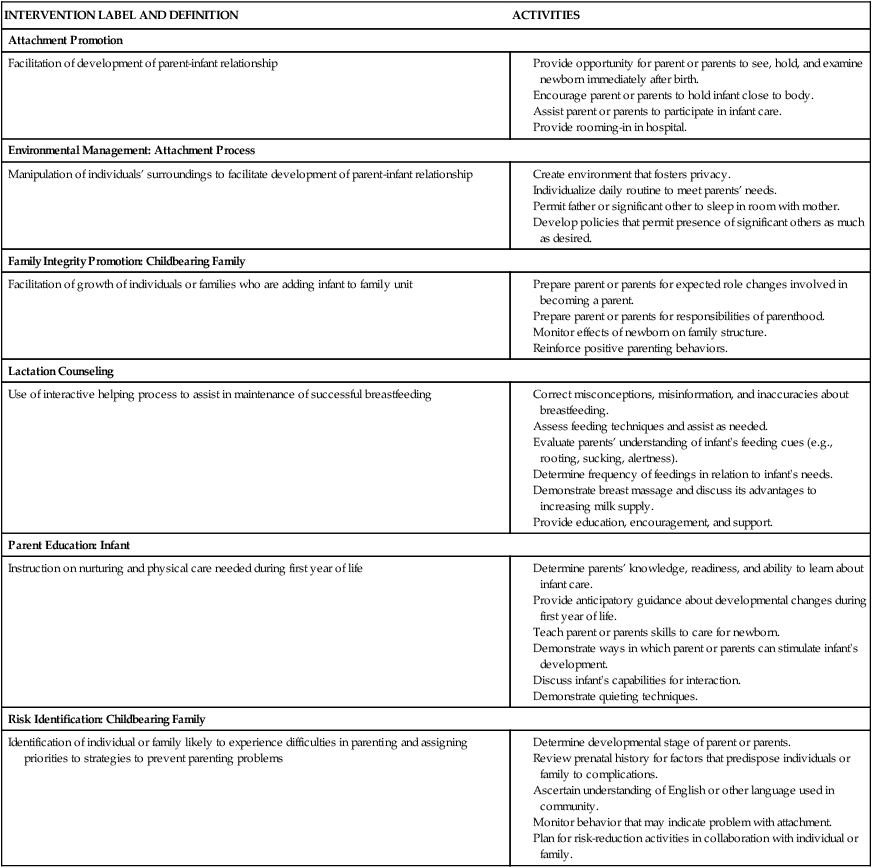

• Identify parental and infant behaviors that facilitate and those that inhibit parental attachment. • Describe sensual responses that strengthen attachment. • Examine the process of becoming a mother and becoming a father. • Compare maternal adjustment and paternal adjustment to parenthood. • Describe how the nurse can facilitate parent-infant adjustment. • Examine the effects of the following on parental response: parental age (i.e., adolescence and older than 35 years), social support, culture, socioeconomic conditions, personal aspirations, and sensory impairment. • Describe sibling adjustment. The process by which a parent comes to love and accept a child and a child comes to love and accept a parent is known as attachment. Using the terms attachment and bonding, Klaus and Kennell proposed that the period shortly after birth is important to mother-to-infant attachment. They defined the phenomenon of bonding as a sensitive period in the first minutes and hours after birth when mothers and fathers must have close contact with their infants for optimal later development (Klaus & Kennell, 1976). Klaus and Kennell (1982) later revised their theory of parent-infant bonding, modifying their claim of the critical nature of immediate contact with the infant after birth. They acknowledged the adaptability of human parents, stating that more than minutes or hours were needed for parents to form an emotional relationship with their infants. The terms attachment and bonding continue to be used interchangeably. Attachment is developed and maintained by proximity and interaction with the infant, through which the parent becomes acquainted with the infant, identifies the infant as an individual, and claims the infant as a member of the family. Positive feedback between the parent and the infant through social, verbal, and nonverbal responses (whether real or perceived) facilitates the attachment process. Attachment occurs through a mutually satisfying experience. A mother commented on her son’s grasp reflex, “I put my finger in his hand, and he grabbed right on. It is just a reflex, I know, but it felt good anyway” (Fig. 15-1). The concept of attachment includes mutuality; that is, the infant’s behaviors and characteristics elicit a corresponding set of parental behaviors and characteristics. The infant displays signaling behaviors such as crying, smiling, and cooing that initiate the contact and bring the caregiver to the child. These behaviors are followed by executive behaviors such as rooting, grasping, and postural adjustments that maintain the contact. Most caregivers are attracted to an alert, responsive, cuddly infant and repelled by an irritable, apparently disinterested infant. Attachment occurs more readily with the infant whose temperament, social capabilities, appearance, and gender fit the parent’s expectations. If the infant does not meet these expectations, the parent’s disappointment can delay the attachment process. Table 15-1 presents a comprehensive list of classic infant behaviors affecting parental attachment. Table 15-2 presents a corresponding list of parental behaviors that affect infant attachment. TABLE 15-1 Infant Behaviors Affecting Parental Attachment Source: Gerson, E. (1973). Infant behavior in the first year of life. New York: Raven Press. TABLE 15-2 Parental Behaviors Affecting Infant Attachment Source: Mercer, R. (1983). Parent-infant attachment. In L. Sonstegard, K. Kowalski, & B. Jennings (Eds.), Women’s health (Vol. 2), Childbearing. New York: Grune & Stratton. An important part of attachment is acquaintance. Parents use eye contact (Fig. 15-2), touching, talking, and exploring to become acquainted with their infant during the immediate postpartum period. Adoptive parents undergo the same process when they first meet their new child. During this period, families engage in the claiming process, which is the identification of the new baby (Fig. 15-3). The child is first identified in terms of “likeness” to other family members, then in terms of “differences,” and finally in terms of “uniqueness.” The unique newcomer is thus incorporated into the family. Mothers and fathers examine their infant carefully and point out characteristics that the child shares with other family members and that are indicative of a relationship between them. Maternal comments such as the following reveal the claiming process: “Everyone says, ‘He’s the image of his father,’ but I found one part like me—his toes are shaped like mine.” Nursing interventions related to the promotion of parent-infant attachment are numerous and varied (Table 15-3). They can enhance positive parent-infant contacts by heightening parental awareness of an infant’s responses and ability to communicate. As the parent attempts to become competent and loving in that role, nurses can bolster the parent’s self-confidence and ego. Nurses are in prime positions to identify actual and potential problems and collaborate with other health care professionals who will provide care for the parents after discharge. Nursing considerations for fostering maternal-infant bonding among special populations may vary (Cultural Considerations box). TABLE 15-3 Examples of Parent-Infant Attachment Interventions Modified from Bulechek, G. M., Butcher, H. K., & Dochterman, J. M. (2008). Nursing interventions classification (NIC) (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. One of the most important areas of assessment is careful observation of specific behaviors thought to indicate the formation of emotional bonds between the newborn and the family, especially the mother. Unlike physical assessment of the neonate, which has concrete guidelines to follow, assessment of parent-infant attachment relies more on skillful observation and interviewing. Rooming-in of mother and infant and liberal visiting privileges for father or partner, siblings, and grandparents provide nurses with excellent opportunities to observe interactions and identify behaviors that demonstrate positive or negative attachment. Attachment behaviors can be easily observed during infant feeding sessions. Box 15-1 presents guidelines for assessment of attachment behaviors. Early skin-to-skin contact between the mother and newborn immediately after birth and during the first hour facilitates maternal affectionate and attachment behaviors (Flacking, Lehtonen, Thomson, et al., 2012; Hung & Berg, 2011; Moore, Anderson, Bergman, et al., 2012). It also enhances breastfeeding and is associated with improved thermoregulation. Touch, or the tactile sense, is used extensively by parents as a means of becoming acquainted with the newborn. Many mothers reach out for their infants as soon as they are born and the cord is cut. Mothers lift their infants to their breasts, enfold them in their arms, and cradle them. Once the infant is close, the mother begins the exploration process with her fingertips, one of the most touch-sensitive areas of the body. Within a short time she uses her palm to caress the baby’s trunk and eventually enfolds the infant. Similar progression of touching is demonstrated by fathers, partners, and other caregivers. Gentle stroking motions are used to soothe and quiet the infant; patting or gently rubbing the infant’s back is a comfort after feedings. Infants also pat the mother’s breast as they nurse. Both seem to enjoy sharing each other’s body warmth. Parents seem to have an innate desire to touch, pick up, and hold the infant (Fig. 15-4). They comment on the softness of the baby’s skin and note details of the baby’s appearance. As parents become increasingly sensitive to the infant’s like or dislike for different types of touch, they draw closer to the baby. Touching behaviors by mothers vary in different cultural groups. For example, minimal touching and cuddling is a traditional Southeast Asian practice thought to protect the infant from evil spirits. Because of tradition and spiritual beliefs, women in India and Bali have practiced infant massage since ancient times (Giger, 2012). Parents repeatedly demonstrate interest in having eye contact with the baby. Some mothers remark that once their babies have looked at them, they feel much closer to them. Parents spend much time getting their babies to open their eyes and look at them. In the United States, eye contact appears to reinforce the development of a trusting relationship and is an important factor in human relationships at all ages. In other cultures, eye contact is perceived differently. For example, in Mexican culture, sustained direct eye contact is considered rude, immodest, and dangerous for some. This danger may arise from the mal de ojo (evil eye), resulting from excessive admiration. Women and children are thought to be more susceptible to the mal de ojo (Giger, 2012). As newborns become functionally able to sustain eye contact with their parents, they spend time in mutual gazing, often in the en face position, a position in which the parent’s face and the infant’s face are approximately 20 cm apart and on the same plane (see Fig. 15-2). Nurses and physicians or midwives can facilitate eye contact immediately after birth by positioning the infant on the mother’s abdomen or breasts with the mother’s and the infant’s faces on the same plane. Dimming the lights encourages the infant’s eyes to open. To promote eye contact, instillation of prophylactic antibiotic ointment in the infant’s eyes can be delayed until the infant and parents have had some time together in the first hour after birth. The fetus is in tune with the mother’s natural rhythms—biorhythmicity—such as her heartbeat. After birth the mother’s heartbeat or a recording of a heartbeat can soothe a crying infant. One of the newborn’s tasks is to establish a personal biorhythm. Parents can help in this process by giving consistent loving care and using their infant’s alert state to develop responsive behavior and thereby increase social interactions and opportunities for learning (Fig. 15-5). The more quickly parents become competent in child care activities, the more quickly they can direct their psychologic energy toward observing and responding to the communication cues the infant gives them. The term synchrony refers to the “fit” between the infant’s cues and the parent’s response. When parent and infant experience a synchronous interaction, it is mutually rewarding (Fig. 15-6). Parents need time to interpret the infant’s cues correctly. For example, after a certain time the infant develops a specific cry in response to different situations such as boredom, loneliness, hunger, and discomfort. The parent may need assistance in interpreting these cries, along with trial and error interventions, before synchrony develops.

Transition to Parenthood

Parental Attachment, Bonding, and Acquaintance

FACILITATING BEHAVIORS

INHIBITING BEHAVIORS

Visually alert; eye-to-eye contact; tracking or following of parent’s face

Sleepy; eyes closed most of the time; gaze aversion

Appealing facial appearance; randomness of body movements reflecting helplessness

Resemblance to person parent dislikes; hyperirritability or jerky body movements when touched

Smiles

Bland facial expression; infrequent smiles

Vocalization; crying only when hungry or wet

Crying for hours on end; colicky

Grasp reflex

Exaggerated motor reflex

Anticipatory approach behaviors for feedings; sucks well; feeds easily

Feeds poorly; regurgitates; vomits often

Enjoys being cuddled and held

Resists holding and cuddling by crying, stiffening body

Easily consolable

Inconsolable; unresponsive to parenting, caretaking tasks

Activity and regularity somewhat predictable

Unpredictable feeding and sleeping schedule

Attention span sufficient to focus on parents

Inability to attend to parent’s face or offered stimulation

Differential crying, smiling, and vocalizing; recognizes and prefers parents

Shows no preference for parents over others

Approaches through locomotion

Unresponsive to parent’s approaches

Clings to parent; puts arms around parent’s neck

Seeks attention from any adult in room

Lifts arms to parents in greeting

Ignores parents

FACILITATING BEHAVIORS

INHIBITING BEHAVIORS

Looks; gazes; takes in physical characteristics of infant; assumes en face position; eye contact

Turns away from infant; ignores infant’s presence

Hovers; maintains proximity; directs attention to, points to infant

Avoids infant; does not seek proximity; refuses to hold infant when given opportunity

Identifies infant as unique individual

Identifies infant with someone parent dislikes; fails to recognize any of infant’s unique features

Claims infant as family member; names infant

Fails to place infant in family context or identify infant with family member; has difficulty naming

Touches; progresses from fingertip to fingers to palms to encompassing contact

Fails to move from fingertip touch to palmar contact and holding

Smiles at infant

Maintains bland countenance or frowns at infant

Talks to, coos, or sings to infant

Wakes infant when infant is sleeping; handles roughly; hurries feeding by moving nipple continuously

Expresses pride in infant

Expresses disappointment, displeasure in infant

Relates infant’s behavior to familiar events

Does not incorporate infant into life

Assigns meaning to infant’s actions and sensitively interprets infant’s needs

Makes no effort to interpret infant’s actions or needs

Views infant’s behaviors and appearance in positive light

Views infant’s behavior as exploiting, deliberately uncooperative; views appearance as distasteful, ugly

Assessment of Attachment Behaviors

Parent-Infant Contact

Early Contact

Communication Between Parent and Infant

The Senses

Touch

Eye contact

Biorhythmicity

Reciprocity and Synchrony

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access