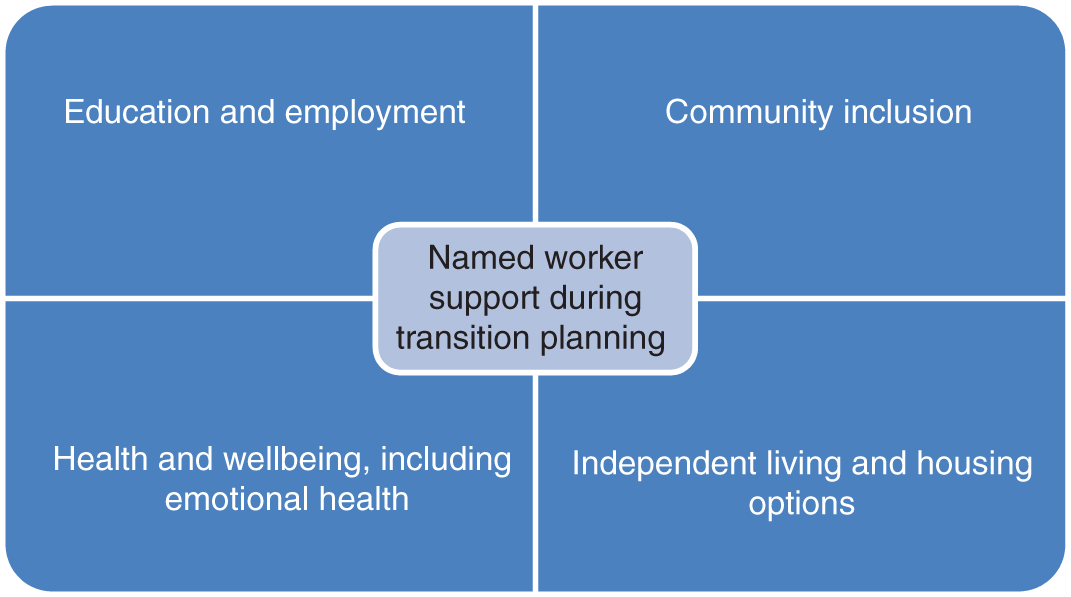

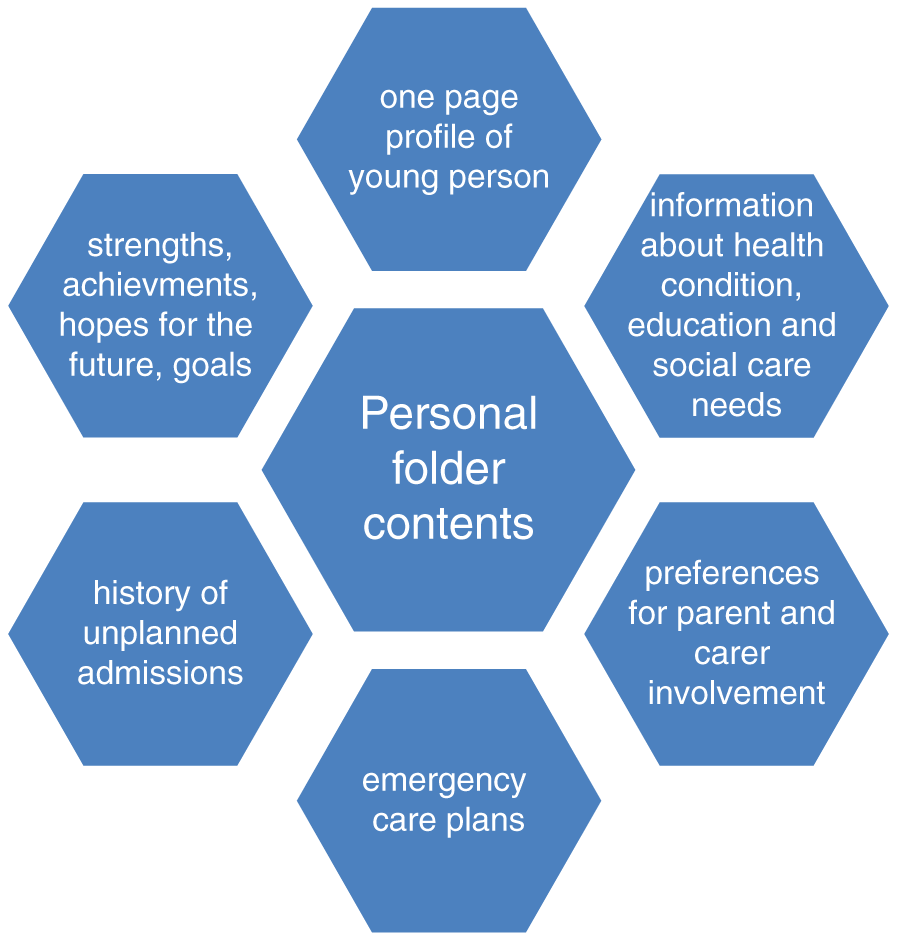

Claire Kerr Adequate planning and smooth transition of healthcare services for children and young people approaching adulthood are important, particularly for those with long-term conditions. All young people experience challenges during the teenage years, such as physical and psychological changes, education, employment and living arrangement options, increased personal responsibility, and a move towards adulthood. Young people with long-term health conditions may also be taking increased responsibility for their own healthcare, typically against a backdrop of changes in service provision and provider(s). This chapter addresses young people’s transition from children’s to adults’ healthcare services and focuses on transition for children and young people with cerebral palsy as an exemplar condition. A generic definition of transition is ‘the process or a period of changing from one state or condition to another’ (Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries 2022). Some examples of transition in healthcare services for children and young people (and their families) include: However, within children and young persons’ healthcare, transition most commonly refers to the transfer of services from paediatric teams to adults’ services. Transition, in this context, has been defined as ‘the purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions from child-centred to adult-oriented healthcare systems’ (Campbell et al. 2016). Further, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) define transition as ‘the process of moving from children’s to adults’ services. It refers to the full process including initial planning, the actual transfer between services, and support throughout’ (NICE 2016). Cerebral palsy is an umbrella term for a group of lifelong disorders of movement and posture. Defined as ‘a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation that are attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing foetal or infant brain. The motor disorders of cerebral palsy are often accompanied by disturbances of sensation, perception, cognition, communication, and behaviour, by epilepsy, and by secondary musculoskeletal problems.’ (Rosenbaum et al. 2007). It is the commonest cause of physical disability in childhood, affecting approximately one in 500 children in high-income countries (McIntyre et al. 2022). Survival of people with severe cerebral palsy has improved in recent decades (Blair et al. 2019). The Northern Ireland Cerebral Palsy Register (NICPR) recently reported that over 90% of people with cerebral palsy survive into adulthood (McConnell et al. 2021). This means that most children with cerebral palsy will require transition planning and, for some young people with severe cerebral palsy, co-ordination of many different healthcare specialities will be required during the transition process. Despite agreed principles in relation to what constitutes good transitional care, there remain challenges in implementation within practice. A sudden move to adults’ services, with no time for preparation or support, can lead to children and young people and families losing confidence and disengaging with services (Watson et al. 2011). Lack of information about the transition process and future adult services is a known barrier to successful transition (Freeman et al. 2018). An important report from the Care Quality Commission (CQC 2014) on transition to adult services for young people with complex physical health needs noted that ‘young people and families are often confused, and at times distressed by the lack of information, support and services available to meet their complex health needs.’ Refer to Box Activity 38.1. For young people with cerebral palsy, who may have complex healthcare needs, difficulties with transition are possible due to the range of services required and the co-ordination of these. Indeed, these difficulties ‘are compounded’ by differences in the funding and organisation of child and adult services. For example, in the UK and Ireland, care co-ordination in childhood is typically managed by a paediatrician (Solanke et al. 2018), but after discharge from children’s services, young people rely increasingly on general practitioners (GPs) (National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death [NCEPOD] 2018; Tuffrey & Pearce 2003). However, in a recent study in Ireland, only 10% of young people with cerebral palsy reported that their GP had received a discharge letter about them (Ryan et al. 2022). The limited involvement of GPs in transition planning (Colver et al. 2020) and limited training of adult healthcare professionals in conditions with childhood onset, such as cerebral palsy, are known barriers to successful transition (Kolehmainen et al. 2017; Tuffrey & Pearce 2003). Transition from child to adult health services for young people with cerebral palsy has been shown to coincide with a decrease in visits to specialist and coordinated services, difficulties accessing clinical care (Roquet et al. 2018) and an increase in unmet health needs (Solanke et al. 2018). In addition to these significant issues with the healthcare system and staff training, problems with transition may also exist in relation to the paediatric team, the young person and the family/carers (Tuffrey & Pearce 2003). For example, paediatricians may be reluctant to move young people on to adult services, especially if they believe those services to be lesser than the care the young person has received to date. The young person may feel ‘abandoned’ by their paediatric team, who they may have known for most of their life and will require time to navigate and build rapport and trust with a new team/teams in adult services (Bagatell et al. 2017; NCEPOD, 2018). Indeed, some parents may perceive a ‘loss of control’ as the young person enters adulthood and assumes increasing autonomy over their healthcare (Tuffrey & Pearce 2003), although interestingly, Ryan et al. (2022) reported that the majority of both young people (90%) and parents (81%) agreed that they were involved at an appropriate level in the young person’s care. Many young people with cerebral palsy do not experience practices that are thought to improve the experience and outcomes of transition (Ryan et al. 2022) despite clear recommendations from substantive programmes of research (Colver et al. 2020) and robust systematic review evidence (Campbell et al. 2016). Further, significant reports highlight: These reports and publication of UK transition guidelines by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence in 2016 suggests that improving the experience and outcomes of transition should be a priority for everyone working with children, young adults, and their families. Refer to Box Activity 38.2. Early planning for the transfer from children’s to adults’ services can lead to a better experience of transition for children and young people by allowing a more gradual process, in which children and young people have more time to be involved in decisions and more time to adjust to changes in their future care. In 2016 NICE published guidelines on transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people. These guidelines are important as they apply across the full spectrum of health and social care, from service users to commissioners of services, developed following a rigorous evidence review and consideration by experts, including people with lived experience. The recommendations in the NICE guidelines on transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social care services are structured under five key areas (NICE, 2016). These are summarised in the following sections to provide a comprehensive overview of how healthcare professionals, including nurses, can support young people’s experiences of transition. The overarching principles of transition put the young person and their carer’s at the heart of the process, aligning with the principles of person and family centred care that prevail in paediatric healthcare (O’Connor et al. 2019; Uniacke et al. 2018). Children and young people, and their carer’s, should be involved in transition service design, delivery and evaluation. In practical terms, this could mean that children and young people co-produce transition policies, strategies and resources in partnership with service organisations. Children and young people could also provide feedback as to whether the services they received were useful. Overall, the transition support that is provided to children, young people, and their carers should be developmentally appropriate, strengths-based, and person-centred: In relation to overarching principles of transition, it is recommended that children’s and adults’ services should work together, proactively plan for transition, share safeguarding information and check the young person is registered with a GP. There are five detailed areas in the NICE guidelines in relation to recommendations for transition planning (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2016). They are: FIGURE 38.1 Aspects of transition that a named worker will offer support with during transition planning. The NICE guidelines recommend that a practitioner from the relevant adult services meets the young person before they transfer from children’s services and that a contingency plan is in place if the named worker leaves their position, thus ensuring consistent transition support is available (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2016). Indeed children and adults’ services should give young people and their families’ accessible information about what to expect from services and what support is available to them. Children’s services should consider working with the young person to create a personal folder that they share with adults’ services. Information that could be included in the personal folder is detailed in Figure 2. The named worker will help the young person become familiar with adults’ health and social care services they may potentially use. Refer to Figure 38.2. FIGURE 38.2 Information that could be included in a young person’s personal folder that they share with adult services to plan transition. Overall, the support after transfer is aimed at stability and continuity of care for the young person. For example, the NICE guidelines state that the young person should see the same healthcare practitioner in adults’ services for the first two attended appointments after transfer and that the same social worker should be involved throughout the transition process (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2016). If the young person does not meet or engage with adult services (after transfer) the adult service should follow up with the young person, their family, and relevant healthcare professionals including the GP. If there is any continued dis-engagement the young person should be referred back to the transition named worker who will review the transition plan with the young person to help them use the service or identify an alternative way to meet their support needs. As recommended, it is important to ensure that there is ownership and accountability for development and implementation of transition strategies and policies in both children and adults’ services (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2016). Service managers should ensure availability of developmentally appropriate services to support transition, such as age-banded clinics. Managers should also consider that young people in receipt of care from multiple medical specialities benefit from care co-ordination from a single healthcare professional. Services should consider use of advocacy to support young people after transfer, and youth forums to provide feedback on services and identify gaps in transitional care. Service provision should be evaluated using data from different agencies and stakeholders. Refer to Box Activity 38.3.

CHAPTER 38

Transition from Children’s to Adults’ Services

DEFINITIONS

CONTEXT

TRANSITION GUIDELINES

OVERARCHING PRINCIPLES OF TRANSITION

TRANSITION PLANNING

SUPPORT BEFORE TRANSFER

SUPPORT AFTER TRANSFER

SUPPORTING INFRASTRUCTURE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree