CHAPTER 8 Time to pause

giving and receiving feedback in clinical education

THEORIES

In this chapter Positioning Theory (Harré & van Langenhove 1999) is applied as an analytical lens to study how students and educators interact in verbal feedback encounters. Positioning theory highlights the fine-grained social mechanics of the feedback sessions, and the mutually constructed and sanctioned ‘roles’ within the educational relationship. In addition, theories of critical reflection resonate through out the chapter, and underpin the practical recommendations for improving student agency, and feedback delivery and utility in clinical education.

USING THEORIES TO INFORM CURRICULUM DESIGN AND RESEARCH

During clinical placements, it is important to factor in opportunities for educators and students to discuss their expectations of the feedback process. The newly conceptualised feedback model presented in this chapter reinforces the importance of student self-evaluation during feedback sessions, and highlights that such reflection—time to pause—demands time, patience, intention and skill on behalf of the educator and the student. Educators’ ‘diagnostic tendency’ in feedback often represents a translation from their clinical role where there is an emphasis on problem identification. This reinforces the need for formal upskilling of clinical educators in educational theory and practices to decrease a tendency to rely on extrapolation of knowledge and techniques from their clinical practice.

Introduction

Feedback is key to learning, offering information on actual performance in relation to the intended goal of performance (Van de Ridder et al 2008, Askew 2000). In clinical education, feedback is used to identify students’ strengths and weaknesses in performance, thereby promoting learning and behavioural change. Feedback can also provide motivation and has the potential to guide the student towards self-regulated practice (Molloy & Clarke 2005). Descriptors of effective feedback include that the message should be timely, based on first-hand data, focused on behaviours rather than learner qualities, and the provider and recipient should be positioned as allies during the interaction (Ende et al 1995, Latting 1992, Pendleton et al 1984). Although there is a growing body of literature devoted to feedback, distinct gaps remain in our understanding of the process and its impact on professional skill development (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick 2006, Mugford et al 1991, Kluger & DeNisi 1996). This lack of clarity is largely due to the fact that feedback is a complex intervention that is dependent on the characteristics of the learning context, the source of the feedback, the individual recipient, and the message generated. It is the multidimensional nature of the process that makes the analysis of feedback interactions so challenging (Bucknall 2007, Ende et al 1995).

This chapter has three aims. First, I will present the dominant conceptual ideas framing the delivery of feedback, most of which are derived from speculative or descriptive studies. Second, I will present the key aspects of an empirical study investigating face-to-face feedback in physiotherapy clinical education (Molloy 2006). Triangulation of perspectives underpins the methodological design of the research, where interpretation of the feedback process is provided by the students (self-report), clinical educators (self-report), and the researcher (observational data). Third, based on the empirical research findings, I will present recommendations for understanding and implementing effective feedback in clinical education that privileges the agentic and self-evaluative capacity of the learner.

Feedback literature

The dominant message in feedback literature is that feedback is problematic, both for the provider and the recipient (Henderson et al 2005, Ilgen & Davis 2000, Glover 2000, Ende et al 1995). Feedback has been described as ‘hard to give, and hard to take’. In addition to the function of collecting data on student performance and synthesising this information into a meaningful and constructive message, the providers of feedback have to negotiate considerable social tensions in attempts to modify students’ learning (Ende et al 1995). In the clinical education context, students are required to ‘hear’ the message, deconstruct it and reconstruct it in light of their current practice wisdom and, finally, act on the feedback. That is, students are expected to translate their clinical educator’s advice into behaviour change. There is much written on the tendency for learners to react defensively to comment on their performance. Consequently much of the literature on feedback focuses on methods of ‘gentle and diplomatic’ feedback delivery.

Equally, clinical educators have reported feedback provision as challenging. Ende et al (1995) and Higgs et al (2004) suggest that clinical educators are required to balance a number of agendas when providing feedback, including protecting the patient, professional standards, and the self-esteem of the student. Educators have a responsibility to provide honest and accurate feedback, while balancing the social or affective needs of the junior member in the supervisory relationship. As reported by Higgs et al (2004): ‘Giving feedback that preserves dignity and facilitates ongoing communication between the communication partners, but that also leads to behavioural change, is a challenge’ (p 248).

The suggestion that feedback should be non-judgemental is widely supported (Ende 1983, Henry 1985, Hewson & Little 1998, Glover 2000). However Ende (1983) acknowledged an inherent danger in this ‘non-judgemental approach’. He coined the concept of ‘vanishing feedback’ where the educator neglects to raise an issue for fear of eliciting a negative emotional reaction from the student. The student, in fearing a negative appraisal, may support and reinforce this educator avoidance. The message and the consequent potential for learning can be lost due to the perceived threat that ‘feedback will have effects beyond its intent’ (Ende 1983, p 778). This tension between acting with sensitivity and delivering with honesty presents a challenge to clinical educators. The literature provides clinical examples to demonstrate the potential damage of feedback on students’ confidence, whether this be through the content of the message or the style of delivery (Cox & Ewan 1988, Stough & Emmer 1998). However clinical educators need to be aware of Ende’s (1983) notion of ‘vanishing feedback’, where learning opportunities can be lost at the expense of attending to the student’s emotional needs.

Another problematic feature of formal, face-to face feedback is that it has both learning and evaluative functions, and both students and educators have reported this tension in practice (Molloy & Clarke 2005, Glover 2000). Educators must position themselves to act as both mentor (providing constructive and encouraging support for learning) and assessor (providing judgement on how the learners’ performance relates to practice norms). In drawing from the results of the feedback research, I argue for a shift in the feedback culture away from the didactic delivery of information from educator to student, towards a conversational model where students engage in the evaluative process. My key contention is that in order to achieve this change in culture, students need to develop self-evaluative capacities and need to be provided with space to exercise agency within the feedback interaction. Additionally, I argue for the educational advantages of upskilling students and educators to work within a solution-focused paradigm, instead of engaging in a largely diagnostic process that emphasises problem identification.

An empirical study of feedback

The aim of this research (Molloy 2006) was to observe and analyse the formal feedback interactions between student and clinical educator in physiotherapy clinical education, with the purpose of informing guidelines for effective practice. Formal feedback interactions are defined as the pre-arranged face-to-face sessions designed to discuss the student’s performance. These formalised feedback sessions are embedded within the clinical education curricula in most health professions, and reflect the historical importance afforded to feedback as a learning tool.

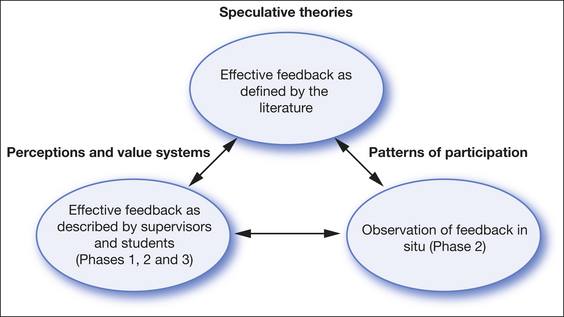

The study used a mainly qualitative methodology and comprised three phases. A unique aspect of the methodology was the triangulation of three data sources, being self-report (interview), observation of practice (videotaping) and literature on best-practice feedback (Fig 8.1). In Phase 1, a questionnaire was designed and administered to elicit clinical educators’ responses regarding current feedback practice, and their perceived affordances and constraints to providing effective feedback. The responses from this questionnaire informed the second phase of the project. Phase 2 involved the videotaping of eighteen formal feedback sessions and follow-up interviews with both students and educators. Phase 3 involved interviews with two key educators affiliated with the University of Melbourne to gain their opinions on the key themes to emerge from the study.

Figure 8.1 The interrelationship between literature, self-reported practice and patterns of participation

Few empirical studies have examined the feedback process in clinical education in situ, with the majority of the recommendations for effective practice based on theoretical constructs. The examination of the relationship between data sources is represented by double arrows in Figure 8.1.

The social practices and expectations implicit in the student–clinical educator interaction were a key focus of the study. Through data analysis, it became apparent that formal feedback constituted an ideal setting in which to: (1) examine the learning relationship between student and clinical educator, and (2) observe students’ engagement with clinical practice and professional identity development. Harré & van Langenhove’s (1999) Positioning Theory, as discussed in Chapter 4, was used as an analytical tool to examine the fine-grained social mechanics of the feedback sessions.

The research design enabled the tracking of students’ progress from the start to the end of the clinical placement and therefore allowed for the examination of professional socialisation. The clinical education literature points to the complexity of the clinical environment and highlights students’ growing independence and confidence as they are progressively socialised into the profession (Rose & Best 2005, Higgs et al 2004). Lave and Wenger (1991) described this phenomenon as ‘legitimate peripheral participation’ where individuals move from novice to expert status. Northedge (2003) also argued for a similar educational philosophy where students, through their participation in the discourse of the profession, are progressively socialised into a practice community.

There were three key findings from the research:

Disjunction between theory and practice

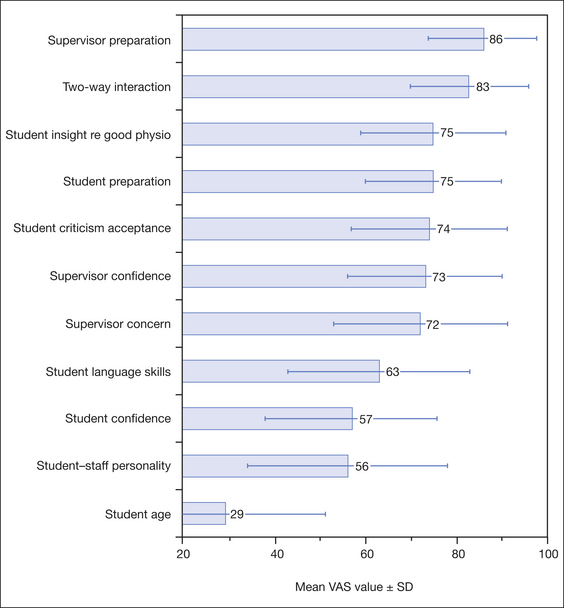

Throughout the study, educators’ descriptions of effective feedback practice were congruent with the espoused principles of ‘best practice feedback’ in the literature. For example, a striking characteristic of the questionnaire data was that clinical educators’ responses closely mirrored the literature on feedback. When asked to rate factors important to an effective feedback session (Fig 8.2), respondents rated all factors except student age highly (where VAS 100 = most important).

In accordance with the results presented in Figure 8.2, participants’ qualitative responses to the open-ended question, ‘What do you view as the key characteristics of effective feedback?’, reflected concepts highlighted in the literature. For example, a participant described ‘effective feedback’ as follows:

At first glance, it may appear an innocuous finding that the participants’ viewpoints corresponded to principles of effective feedback in the literature. However the Phase 2 data showed that the enactment of feedback was distinctly different to the self-reports of effective feedback. The results of the questionnaire (Phase 1) showed that clinical educators supported principles advocated in the literature, including the importance of establishing a two-way interaction in feedback. In practice, however, the feedback sessions did not represent two-way interactions. As stated by Kagan (1988), observational methodology produces different results to self-report methodology. That is, what we do can be quite different to what we say we do, without necessarily reflecting an intention to deceive. The findings in this study reinforce the importance of triangulation of data sources in building an authentic picture of practice, and motivations for practice. The disjunction between theory and practice also calls for the detailed examination of factors that constrain educators and students from enacting their vision of ideal practice.

Formal feedback: a monologic culture

The key finding to emerge from the video-recording of the formal feedback encounters was that there was minimal input from the students in the sessions. Despite the educators providing students with an opportunity for self-evaluation at the start of most feedback sessions, students rarely took up this opportunity for engagement. In the eighteen videotaped interactions, there was no evidence of students collaborating to develop goals or strategies for improvement. On average, the feedback interactions lasted for 21 minutes, and the students’ contribution accounted for less than two minutes of the ‘conversation’. When interviewed, clinical educators acknowledged the one-way direction of the feedback sessions as indicated below:

Self-evaluation and tokenism

The importance of clinical educator validation of students’ self-analysis in feedback is supported by Frye et al (1997). In their study, Frye and colleagues found that clinical educators validated interns’ self-assessment by either expressing agreement, or engaging the intern in a discussion that related to the issues which the intern voiced. In the research discussed in this chapter, clinical educators changed the direction of conversation swiftly away from students’ self-evaluative comments, and there was seldom evidence of building on students’ comments.

Both students and clinical educators expressed an understanding of the importance of two-way feedback. In sixteen out of eighteen videotaped sessions, clinical educators did provide invitations for student self-analysis, but the student responses in the feedback sessions indicated an expectation of tokenism. That is, students offered a brief account of their clinical experience, most often relating to their enjoyment of the clinical placement, rather than a commentary on learning or performance. The fact that clinical educators condoned this brief, or surface, response indicated that both students and clinical educators had shared expectations about the meaning of the self-evaluative invitation. The positioning dynamics of the educator and learner as described below offer a further explanation as to why students may be reticent to contribute to the feedback dialogue.

The clinical educator positioned as the diagnostician

This asymmetry in conversation observed between students and educators bears distinct resemblance to the asymmetry reported in patient–clinician conversations (Parry 2004). In a study of communicative interactions between physiotherapists and their patients, Parry (2004) found the observed conversations were entirely directed by the physiotherapist. Delany (2006) in a different study of physiotherapist–patient communication also noted the asymmetry in communication that constrained opportunities for patients to add to the conversation. The didactic nature of clinical communicative encounters is supported by Thornquist (1994). ‘The relationship between therapist and patient is in principle asymmetric. The therapist’s professional position enables her not only to define the problem and decide on the treatment, but also to control and define the encounter with the patient’ (p 703).

The results from the feedback study suggested that students were equally responsible for creating this asymmetry in conversation. Students who praised their clinical educators most highly in feedback emerged from case studies where the sessions were shown to be most didactic in nature. Students cooperated with their clinical educator to position the clinical educator as the ‘diagnostic expert’, and did not contest their own positioning as the ‘listener’ in the interaction. This notion of ‘complicity’ was also raised in a study examining general practice consultations by Heath (1992). Heath’s work contributes to the growing body of empirical research challenging the understanding that clinical authority, and the associated asymmetry in clinical interactions, is imposed on patients by clinicians. Consistent with the results of this study, Heath’s research highlights that both patients and clinicians contribute to and in fact produce these features of ‘unequal positioning’ through their communicative actions.

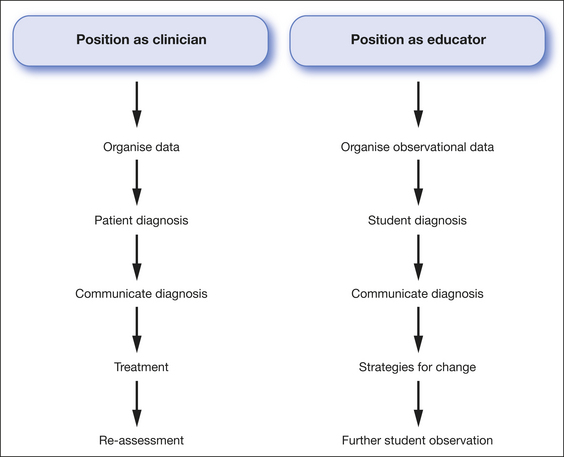

Clinical educators, as health practitioners, are conditioned to work within a biomedical paradigm where they are expected to assess patients, form a diagnosis of the presenting problem, and provide treatment for the problem. The way in which clinical educators provided feedback closely resembled this clinical positioning. Figure 8.3 compares the clinical and educational (giving feedback) demands of clinicians. The two practices share distinctly similar characteristics. The features of diagnosis, presenting data to support the diagnosis and providing treatment strategies, are commonly enacted in both educators’ clinical practice and feedback practice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree