Thrombosis and thromboembolisation250

Introduction

The Nature of the Disease

Thrombosis and Thromboembolisation

Mechanisms

Stagnation of the blood flow

Damage to the vein wall

Abnormalities of the clotting mechanism

Multiple risk factors

Major risk factors

Superficial thrombophlebitis

Deep vein thrombosis

Pulmonary thromboembolism

Reducing the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

Tests to Identify Venous Thromboembolic Disease

Diagnostic approach single : assessing the probability of a PE

Test

Good at:

Poor at:

V/Q lung scan

Diagnosing a PE if the chest film is normal

Diagnosing a PE if there is pre-existing lung disease

Contrast venogram

The ‘gold standard’ test

Too invasive for a screening test (replaced by CTPA)

Impedence plethysmography

Diagnosing a proximal (above knee) DVT

Diagnosing a distal (calf vein)

DVT

D-dimers

Excluding a DVT if the test is normal.

Also positive in PE

False positive result in other conditions, e.g. infection and myocardial infarct

Compression ultrasound

A good screening test

Diagnosing a distal (calf vein) thrombosis

CT pulmonary angiogram

Isotope lung scan

D-dimer measurements

Compression ultrasound

Contrast venogram and pulmonary angiogram

Impedance plethysmography

Management of Pulmonary Thromboembolism

CASE 1

CASE 2

Thromboembolic disease

Tests to identify venous thromboembolic disease255

Management of pulmonary thromboembolism257

Nursing the patient with a suspected DVT262

The situation has changed, for two reasons:

• rapid and reliable screening tests are now available for venous thromboembolism

• simplified anticoagulation with once-daily subcutaneous low-molecularweight heparin is replacing the heparin infusion

There are two important clinical issues:

• differentiating between the various causes of a red, swollen and painful leg: venous thrombosis, cellulitis, varicose eczema and arterial insufficiency

• remembering to consider the possibility of pulmonary emboli in any ill and breathless patient – particularly where there is pleuritic chest pain

The overriding consideration in these situations is that a missed diagnosis of venous thromboembolic disease carries with it the potential of a preventable death from a massive pulmonary embolus. It should be remembered that post-mortem studies have shown that 10% of hospital deaths are due to pulmonary emboli; most of them were unrecognised.

Thrombosis refers to the process in which a mass of clot forms inside an artery or a vein. It consists of a dense network of fibrin in which are trapped variable proportions of red cells and platelets. Thrombosis blocks the vessel and impairs blood flow. Arterial thrombosis leads to ischaemic tissue damage (myocardial infarction, stroke and peripheral vascular disease), whereas in venous thrombosis the consequences are due to back pressure and local swelling (oedema). If the clot disintegrates, parts of it can break off, producing emboli that travel onwards – in venous thrombosis through the veins to the lungs (pulmonary embolus), and in arterial thrombosis through the arteries to major organs such as the brain (cerebral embolus), limbs (peripheral embolus), kidneys (renal infarction) and intestine (acute bowel ischaemia).

Stagnation within the veins is the most important factor in initiating venous thrombosis. Calf muscles act as a venous pump returning blood to the heart. Failure of the calf pump due to enforced immobility (e.g. postoperative bed rest, plaster cast, paralysed limb) leads to venous stasis. This is a particular problem in the elderly, the obese and those with varicose veins: in these patients even 3 or 4 days of immobility can be critical.

Thrombosis is triggered by the activation of clotting mechanisms that occurs when there is damage to the vein wall – indeed, this is the normal mechanism for preventing bleeding at the sites of trauma. Typical situations that lead to vein damage are pressure injuries to the calf from the operating theatre table and the deterioration that occurs in the veins as a result of recurrent venous thrombosis.

There are several inherited and acquired abnormalities of the clotting mechanisms that increase the risk of venous thromboembolic disease (→Box 7.1). The most common acquired abnormalities are those associated with the oral contraceptive pill, hormone replacement therapy, pregnancy and the presence of malignant disease.

Box 7.1

• Antithrombin deficiency

• Protein C deficiency

• Antiphospholipid syndrome

• Protein S deficiency

• Factor V Leiden

Inherited clotting abnormalities (‘thrombophilias’) are increasingly recognised as underlying the cause of recurrent DVTs, particularly in younger patients and in those with a positive family history. The most important of several inherited coagulation abnormalities, known as Factor V Leiden, is present in 5% of the population and increases the risk of thrombosis by ten times the normal rate. One in five patients with their first DVT are Factor V Leiden positive. Recent estimates suggest up to half of all patients who present with a venous thromboembolic episode, either DVT or pulmonary embolus, may have a single or multiple inherited abnormalities of their clotting. In these individuals, each episode can be triggered by trivial external events such as minor surgery or immobility. In the future, increasing attention will be paid to identifying these inherited risk factors.

In most situations in which the chances of a venous thrombosis are high there are multiple risk factors. Thus in major orthopaedic procedures to the leg there is vein damage and immobility; in pregnancy there is abnormal clotting and stagnation of blood due to intraabdominal mechanical effects; and in prolonged air travel there is immobility, often associated with a degree of dehydration. The combination of the oral contraceptive pill and the presence of Factor V Leiden increases the risk of a DVT 30-fold.

In a patient with suspicious symptoms, the presence of major risk factors (those that increase the risk by between 5 and 20 times normal) makes the diagnosis of a pulmonary embolism much more likely.

• Recent surgery (hip and knee replacement, major abdominal and pelvic surgery)

• Decreased mobility (institutional care, prolonged hospital stay)

• Malignancy

• Lower limb problems (post phlebitic limb, varicose veins)

• Pregnancy (not the pill) especially third trimester and post delivery/ caesarian

• Previous DVT/PE

Thrombophlebitis is a painful inflammation of the superficial veins. Classically it is seen with infected venous cannulae, but it also commonly occurs in patients with varicose veins. The clinical picture is of palpable and very tender cords of thrombosed and inflamed veins, with the overlying skin appearing reddened or bruised. Thrombophlebitis is not in itself dangerous: it does not progress to, but may accompany, deep vein thrombosis. Management is based on removing any cause (e.g. an i.v. cannula) and treating the symptoms. Importantly, recurrent unexplained phlebitis is found in patients with unrecognised malignant disease, particularly adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract and lung.

Deep vein thrombosis is a more serious problem, because of the risk of fatal pulmonary embolus. Most DVTs start in the deep veins of the calf, termed the distal veins, where they cause local pain and swelling.

The management is based on preventing progression of the thrombotic process by using heparin for an immediate effect, followed by warfarin in the medium to long term to lower the risk of recurrence. The aim of treatment is to stabilise the situation. Warfarin and heparin do not dissolve established clots: they are given to:

• prevent extension

• reduce the chances of embolisation

• lower the risk of recurrence

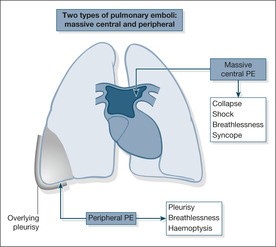

Most pulmonary emboli (90%) arise from the proximal veins in the thigh and pelvis. Depending on their size, emboli that travel to the lung either become wedged in the main pulmonary arteries, where they block the outflow of blood from the right side of the heart, or pass onwards to become trapped in the lung peripheries. The former, termed massive pulmonary emboli, produce a disastrous decrease in cardiac output, leading to sudden death or acute hypotensive collapse. The smaller emboli in the periphery of the lungs produce wedge-shaped areas of lung damage (producing breathlessness and haemoptysis) and give rise to overlying pleurisy (acute chest pain and a fever; →Fig. 7.1).

Massive pulmonary emboli can move or start to break up either naturally or during the course of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Thrombolytic drugs such as streptokinase and rt-PA can help to dissolve the embolus and are used in the unstable hypotensive patient. Heparin will prevent further emboli, and as most patients who survive the first embolus die from a recurrence within the first few hours, it is important to start treatment urgently. Warfarin is added for longer-term prevention.

The management of smaller peripheral emboli is based on preventing further and possibly bigger emboli by giving heparin and, subsequently, warfarin.

There is a significant risk that the admission of a patient with an acute medical illness is complicated by a DVT and/or pulmonary embolus. This risk should be assessed in every patient and if it is significant, preventative measures – either drugs (LMWH or fondaparinix) or mechanical measures (thigh-length anti-embolism stockings) should be considered.

Significant risk of VTE in an acute medical admission is defined as:

• decreased mobility anticipated for three days or more or one or more of the following risk factors

• age > 60

• obese (BMI > 30)

• medical co-morbidities (diabetes, CCF, COPD, chronic arthritis etc.)

• active malignancy

• phlebitic lower limbs

• pregnant with an associated risk factor (e.g. age >35, hyperemesis, ovarian hyperstimulation)

• HRT or the oral contraceptive

Confirmatory tests are chosen according to the clinical likelihood of a PE and the presence or absence of major risk factors (page 254). If the clinical picture is consistent with a PE, and the patient has no other obvious alternative diagnosis such as pneumonia or COPD, the presence of a major risk factor makes the probability of a PE high. If the clinical picture is consistent with a PE but the patient has either no obvious alternative diagnosis or a major risk factor, the probability of a PE is intermediate. If the clinical picture would fit a PE but there is an obvious alternative diagnosis and no major risk factor, the probability of a PE is low. High probability patients should start heparin immediately and need a definitive test (CTPA or isotope lung scan) – patients where the probability of a PE is intermediate or low should have the screening blood test (D-dimer) which, if it is normal, rules out a PE. A normal D-dimer test can give false reassurance in cases where the clinical suspicion is scored high – in this situation the test should not be done.

A number of tests are available to identify venous thromboembolic disease (→Table 7.1). They are described in more detail below.

The investigation of possible pulmonary emboli has been revolutionised by the introduction of the CTPA. It is superior to both the isotope lung scan and the conventional angiogram. A negative CTPA rules out a significant pulmonary embolus and often gives additional information on alternative causes of the patient’s symptoms.

Lung scans are easy to perform and, when used in conjunction with the clinical details, are useful in the diagnosis of pulmonary emboli. Although positive scans are also seen in other conditions and have to be interpreted with care, a normal scan result is very helpful, as it rules out the possibility of a pulmonary embolus.

D-dimers are fragments of dissolving blood clots that can be identified from a blood sample whenever a thromboembolic process is under way. A positive test is also seen after surgery, in infections, after myocardial infarction and in malignant disease: a positive D-dimer test is not therefore in itself diagnostic. D-dimer tests are most useful for ruling out thromboembolism when the initial clinical assessment suggests a low or intermediate suspicion of the diagnosis. For example a patient who is breathless may have a major risk factor such as recent hip surgery, but has other possible causes of breathlessness such as COPD: in this situation, a negative D-dimer means there is another cause for the breathlessness. When the clinical suspicion is high, D-dimers are not helpful, because a negative result under these circumstances is not reliable enough to rule out the diagnosis (an example would be a patient who is breathless, with no alternative explanation, plus a major risk factor for pulmonary embolus).

This looks at compressibility of the vein with an ultrasound probe and also examines venous blood flow using colour Doppler. Compression ultrasound is accurate for thigh vein thrombosis, but not for thrombosis in the pelvis or calf. It is also unreliable at picking up recurrent thrombotic episodes. In spite of these drawbacks, ultrasound is a simple, rapid and very effective diagnostic tool, particularly when combined with clinical assessment and initial screening by the measurement of D-dimers. If a DVT is thought likely (based on clinical assessment in the form of a scoring system – page 265 and an elevated D-dimers) but a compression scan is negative, the scan should be repeated in seven days in case a calf vein thrombosis (not dangerous) has extended above the knee to involve the thigh veins (dangerous).

The venogram examines the veins of the legs and pelvis and the inferior vena cava and is considered to be the ‘gold standard’ for the identification of venous thrombosis. An invasive test and unpleasant for the patient, its use is confined to difficult cases, particularly those in which active intervention with a vena cava filter is under consideration. The pulmonary angiogram was the ‘gold standard’ investigation for diagnosing pulmonary emboli, but it has been replaced by the CT pulmonary angiogram.

In this test, the flow of blood out of the calf is impeded by inflating a thigh cuff. The cuff is then suddenly let down and the flow of blood out of the calf is measured to assess the degree of venous obstruction. The term ‘impedance’ refers to the technique of deriving a measure of blood flow from sensors placed over the calf.

Ultrasound and plethysmography are reliable for proximal deep vein thrombosis, but are poor at identifying calf vein thrombosis. However, in practical terms (i.e. the risk of pulmonary embolus) thrombosis in the calf only becomes important if it spreads to the thigh – so if the initial clinical suspicion is high it is prudent to repeat either test after a few days, in case a missed calf vein thrombosis has extended proximally to the thigh.

The following case studies are used to illustrate management of pulmonary thromboembolism (→Case Study 7.1, Case Studies 7.2, Case Study 7.3 and Case Studies 7.4). The classic features of a pulmonary embolus are listed in Box 7.2.

Case Study 7.1

A 35-year-old woman was admitted to hospital having collapsed at home. She had arisen to go to the toilet and collapsed with loss of consciousness for a few seconds. She recovered, but remained clammy with a thready pulse and felt very breathless.The day before, she had complained of a slight pain in the left calf. She was taking a third-generation combined oral contraceptive pill, she was obese and was a smoker. She also had chronic bilateral varicose veins.Three months earlier, she had been admitted with swelling and tenderness of the left calf coming on after exercise, but after equivocal tests had been discharged without anticoagulation.

On examination her pulse was 110 beats/min, blood pressure 104/78mmHg, oxygen saturations 100% on 6L/min oxygen. Respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min.The right calf measured 42cm and the left 46cm (similar readings to the previous admission). An urgent lung scan showed multiple pulmonary emboli. Seven hours after admission, she collapsed again while walking to the toilet, but on this occasion there was a cardiorespiratory arrest. In spite of prolonged resuscitation and the use of streptokinase, she remained in electromechanical dissociation (EMD) and did not survive.

Case Studies 7.2

A 54-year-old woman was admitted with a 1-week history of right upper abdominal pain radiating to her back and right shoulder and worse on lying or on deep inspiration. She had become breathless over 2 days.

On admission the patient had a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, pulse 80 beats/min and normal blood pressure.The arterial oxygen level was reduced to 88% on air and the chest film showed changes at both lung bases. A provisional diagnosis of diaphragmatic pleurisy due to pulmonary emboli was made and heparin was started.

On the second day the oxygen saturations fell to 76% on air and the pulse had increased to 110 beats/min. Examination and ECG showed increasing strain on the right side of the heart. On the third day there was a sudden attack of near syncope and breathlessness on standing associated with further drops in the oxygen saturation and a blood pressure of 90/60mmHg.The oxygen saturation remained low at 85% in spite of high-flow oxygen.

The lung scan showed multiple pulmonary emboli.Thrombolysis with i.v. streptokinase was started: 250 000 units over 30min then 100 000 units hourly for 72h. Her condition improved, with a fall in the pulse rate and an increase in the oxygen saturations.

A subsequent compression ultrasound showed an extensive right-sided proximal DVT.

A 64-year-old woman was admitted with a 5-day history of severe progressive breathlessness and exertional faintness.Two years earlier, extensive investigations for unexplained breathlessness concluded that the diagnosis was hyperventilation.

In her past history there had been extensive plastic surgery to the left calf. On admission she was obese, with bilateral ankle oedema. She was having episodic attacks of breathlessness and pain. Oxygen saturations were dropping to 70% on air. An urgent lung scan showed multiple pulmonary emboli. She was treated with i.v. heparin and then streptokinase, but remained very ill. Combined pulmonary angiogram and venogram showed multiple emboli originating from a left iliac vein thrombosis. A permanent inferior vena cava filter was inserted by the radiologist, to lie in the vena cava just below the renal veins.This prevented further emboli and she slowly recovered.

At review a year later, she remained well, with much improved exercise tolerance and significant weight loss. She was on life-long warfarin.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access